Those Who Are Lost

Written in three parts, this award winning novel by Lebanese author Hada Barakat, is composed of a series of six letters written in a stream of consciousness narrative that are interlinked. The letters are read, but not by their intended recipient, found between the pages of a book, dug out of a bin or otherwise encountered. They prompt the finder to write their own letter.

Written in three parts, this award winning novel by Lebanese author Hada Barakat, is composed of a series of six letters written in a stream of consciousness narrative that are interlinked. The letters are read, but not by their intended recipient, found between the pages of a book, dug out of a bin or otherwise encountered. They prompt the finder to write their own letter.

They are a kind of confession, written by the marginalised, floundering in exile. The letters excavate a depth of feeling that is raw, that traverses memory, hurts, an indifferent ability to cause pain, love, sorrow, longing, an abuse of kindness, a deterioration of the psyche.

“With this novel, I wanted to really listen to those millions of wandering souls who can’t speak for themselves: migrants. Their desperation to leave their country, no matter the cost, even if they know their lives will be at stake.”

Some of the letters are written to a family member, others to a lover, others to nameless recipients.

They are all experiencing deep loss having either been removed from all they’ve known or been connected to, or have been abandoned. Below, I’ve chosen a quote from each letter to give a sense of the narrative.

An undocumented immigrant writes to his former lover. He is unkind and doesn’t understand why she tolerates him. We learn that his mother put him on a train alone when he was eight or nine, effectively abandoning him, a sacrifice to gift him the education she never had. A man across from him is watching him through the window. Paranoia.

I’ve never written a letter in my life. Not a single one. There was a letter in my mind, which I brooded over for years, rewriting it in my head again and again. But I never wrote it down. After all, my mother could hardly read, and so I expect she would have taken my letter to one of the village men with enough education to read it to her. That would have been a disaster though!

Photo by SafaPexels.com

A woman in a hotel room writes to a man from her past. She finds a perplexing letter in the pages of the telephone directory in the room. She wonders whether it was the man who penned it or the woman to which he wrote who left it there and why. It was clearly unfinished. She recalls the sweet succulence of the medlar fruits they ate walking the streets of Beirut.

This sweetness has nothing to do with the act of remembering. It’s not the delicious and sweet because it is linked to the past, to the time of our youth, where nostalgia for that time gives everything we can’t bring back a more beautiful sheen. Nothing in my childhood or my adolescence has ever prompted a longing for the past, a past that seems to me more like a prison than anything else. I am not here in this room in order to return to what was, nor to see you and thus see with you the charming young woman I once was, or how lovely and robust the springtime was that year, there in my home country. That country is gone now, it is finished, toppled over and shattered like a huge glass vase, leaving only shards scattered across the ground. To attempt to bring any of this back would end only in tragedy. It could produce only a pure, unadulterated grief, an unbearable bitterness.

Photo by KoolShootersPexels.com

An escaped torturer recounts his crimes to his mother. He got the idea to write a letter from observing a woman taking some folded papers from her handbag, read them, then tear them in half and drop them in a bin. He retrieves them.

You would say I deserve all this. You might even disown me, calling me the Devil’s offspring. And if I think of my father, I’d have to admit that you have a point. Still, after all that I’ve been through, is there any point in believing that if I asked you to pardon me, you might do it?

I know you won’t, I know there’s really no hope.

A former prostitute writes to her brother. She is on a plane that had been delayed due to the arrest of a passenger. She found a crumpled up letter shoved between the seat and the wall.

I know why security took him away in handcuffs, because I have a letter in my pocket that this man wrote to his mother. He must have tried to hide it before they reached him, because it’s not the kind of letter anyone would just forget about or be careless enough to lose.

A young queer man recounts to his estranged father his partner’s battle with AIDS. He stumbles across a letter written by a woman in a storage locker at a bar he worked in. That was two years ago, recently he reread it.

I read it again and again, as if I knew that woman personally. Or as if I could actually see her in front of me, asking someone’s forgiveness but discovering she could not get it. And not just because her letter would never arrive. It’s about the need we all have for someone to listen to us, and then to decide they will pardon us no matter what we have done.

Those Who Are Searching

In this second part, brief extracts focused on those who have some connection to the letter writers, those who are trying to find their place, searching, also at a loss.

Those Who Are Left Behind

Finally, the mailman leaves his own note, sheltering in the bombed out remains of the post office.

Neither the internet nor anything else would do away with the need for my rounds, not even after internet cafés were springing up everywhere like mushrooms.

Displaced, at a loss, rootless, untethered. Like the roll of the dice they were born into a place and era where stability, home and belonging would be denied them.

Haunting, at times disturbing, it is a compelling read, the rootlessness and isolation felt by the reader, due to the manner in which the letters are written. The edge of despair palpable. It’s as if the one who stayed, surrounded by destruction, is the only one left with a sense of belonging.

Further Reading

Article: The Return of the NonProdigal Sons by Hoda Barakat

Hoda Barakat

Hoda Barakat was born in Beirut in 1952. She has worked in teaching and journalism and lives in France. She has published six novels, two plays, a book of short stories and a book of memoirs, as well as contributing to books written in French. Her work has been translated into a number of languages.

Hoda Barakat was born in Beirut in 1952. She has worked in teaching and journalism and lives in France. She has published six novels, two plays, a book of short stories and a book of memoirs, as well as contributing to books written in French. Her work has been translated into a number of languages.

She received the ‘Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres’ in 2002 and the ‘Chevalier de l’Ordre du Mérite National’ in 2008.

Her novels include: The Stone of Laughter (1990), Disciples of Passion (1993), The Tiller of Waters (2000) which won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature, and My Master and my Lover (2004). The Kingdom of This Earth (2012) reached the IPAF longlist in 2013. In 2015, she was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize, given (at that time) every two years to honour a writer’s achievement in fiction. Voices of the Lost won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction ((IPAF) in 2019.

N.B. Thank you to OneWorld Publications for providing me a review copy

Winter Flowers (Les Fleurs d’hiver) by Angélique Villenueuve, translated by Adriana Hunter is published Oct 7 by

Winter Flowers (Les Fleurs d’hiver) by Angélique Villenueuve, translated by Adriana Hunter is published Oct 7 by

Though the story follows Babakar, each time we encounter a new character, there is this digression into their backstory(s), so we learn of all these male characters stories, Babakar (in Mali and the often present apparition of his mother Thécla Minerve), Movar, (in Haiti) Fouad (in Lebanon, though being Palestinian he dreams of the poetry of Mahmoud Darwich) who all come together in Haiti, and underlying the visit, this search to find family and learn why the young mother had fled.

Though the story follows Babakar, each time we encounter a new character, there is this digression into their backstory(s), so we learn of all these male characters stories, Babakar (in Mali and the often present apparition of his mother Thécla Minerve), Movar, (in Haiti) Fouad (in Lebanon, though being Palestinian he dreams of the poetry of Mahmoud Darwich) who all come together in Haiti, and underlying the visit, this search to find family and learn why the young mother had fled.

I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style.

I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style. The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother.

The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother. A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both

A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both  Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981.

Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981.

What a refreshing read to end 2020 with, a novel of interwoven characters and connections, threaded throughout the life of Violette Touissant, given up at birth.

What a refreshing read to end 2020 with, a novel of interwoven characters and connections, threaded throughout the life of Violette Touissant, given up at birth.

Every summer she stays in the chalet of her friend Célia, in the calanque of Sormiou, Marseille. A place of refuge and rejevenation, that Perrin too brings alive, eliciting the recovery and rehabilitation this nature-protected part of the Mediterranean offers humanity.

Every summer she stays in the chalet of her friend Célia, in the calanque of Sormiou, Marseille. A place of refuge and rejevenation, that Perrin too brings alive, eliciting the recovery and rehabilitation this nature-protected part of the Mediterranean offers humanity.

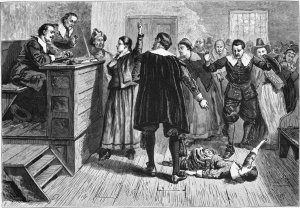

Tituba existed, she was accused and ultimately set free, however, despite the shelves of history books about the Salem witch trials, there is little factual information about her, who she was, who freed her, or her life after release from prison.

Tituba existed, she was accused and ultimately set free, however, despite the shelves of history books about the Salem witch trials, there is little factual information about her, who she was, who freed her, or her life after release from prison. And so Tituba is given a past, skills and knowledge and might have remained in that life, had she not grown into a young woman with desires herself and fallen for the man who would become her husband John Indian.

And so Tituba is given a past, skills and knowledge and might have remained in that life, had she not grown into a young woman with desires herself and fallen for the man who would become her husband John Indian. Like Condé, who said she knew nothing of witchcraft, I have decided to read a contemporary book next, published in 2020, to see what’s going on in the world of witchcraft today.

Like Condé, who said she knew nothing of witchcraft, I have decided to read a contemporary book next, published in 2020, to see what’s going on in the world of witchcraft today. From the opening pages, as Giovanna overhears a random comment from her father, it expands in her mind and overtakes her physically and mentally like a disease, affecting her mind, causing her to act in certain ways.

From the opening pages, as Giovanna overhears a random comment from her father, it expands in her mind and overtakes her physically and mentally like a disease, affecting her mind, causing her to act in certain ways.

As I’m currently reading her most recent novel,

As I’m currently reading her most recent novel,  I’ve also added the countries the author is associated with, either by birth and/or nationality, as I find that helpful, it being one of the criteria by which I decide whether to read a book or not – to avoid always reading works from the same cultural influence.

I’ve also added the countries the author is associated with, either by birth and/or nationality, as I find that helpful, it being one of the criteria by which I decide whether to read a book or not – to avoid always reading works from the same cultural influence.