Undiscovered was longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2024. I decided to read it because I did the quiz on their website which asked about 15 or so questions and then told you which book to read. Undiscovered was the result.

I was totally captivated from start to finish. Loved it.

Ancestral Threads

Gabriela Wiener is a Peruvian poet, journalist, writer who has lived in Spain for the last 20 years and her books to date (none of which I have read) seem to about body politics. This novel is about a search to unravel and understand her identity as a Peruvian woman now living in Spain, who has ties to both the coloniser and the colonised.

I was very intrigued to read this book for a few reasons, of course because it is written by a woman in translation, so that already interests me, because it is coming from outside the mainstream cultures that traditionally dominate publishing and also because of the interest in identity, in the influence of ancestry, of family mysteries uncovered.

The strangest thing about being alone here in Paris, in an anthropology museum gallery more or less beneath the Eiffel Tower, is the thought that all these statuettes that look like me were wrenched from my country by a man whose last name I inherited.

A Temporary Explorer

Gabriela is both fascinated and repelled by a ‘maybe ancestor’ Charles Wiener, an Austrian-Jew whose parents immigrated to France when he was sixteen. He became a German teacher in a French lycée, would convert to Catholicism and desired French nationality. He published an essay on the “communist empire” of the Incas;

a reign based on social equality and therefore, per his thesis, antithetical to freedom. In his writing he defended the delirious hypotheses that Louis XIV had been inspired by the Incas when he said “L’état, c’est moi.”

That publication resulted in the French government agreeing to send him on an expedition to South America in 1876. The studies he conducted and specimens collected would eventually be displayed in a large scale exhibit at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1878. He wrote a book Peru and Bolivia.

On his return to France he was naturalised, retired from exploration and became a diplomat. In the less than two years he was in Peru, he fathered a child to a young widow, Maria Rodriguez. Her son, the author’s great-grandfather, Carlos Wiener Rodriguez, was born in May 1877, by which time Charles Wiener, was already in Bolivia. And most likely oblivious to what he had left behind.

We know everything about him and nothing about her. He left us a book, she left us the possibility of imagination.

The Unfaithful Father

In Undiscovered Gabriela explores the writings of her ancestor and has conflicting feelings about him, as she has conflicting feelings about herself, and her own father. The first half of the book takes place while she is on a return trip to Lima for her father’s funeral. He had a second life and family that he lived simultaneously, one she tries to make sense of by meeting his mistress and asking her mother personal questions.

But really she is interrogating those outside of her to understand something within her. She is of a different generation and even within that she lives an unconventional life. Is she how she is because that is how she is, or is there something of the past that runs through her veins which makes it harder to be anything other than that? Even in her unconventionality, she continues to cross her own boundaries and disappoint herself. She seeks to understand why.

The irritation I feel at the cruel, colonial, and racist passages in the book Wiener wrote about my culture gives way to a sudden compassion for his unwittingly anti-academic, self-aggrandizing self.

A Polyamorous Woman

On an existential quest tracing a legacy of abandonment, jealousy and colonial exploitation, she considers the effect on her own struggles with desire, love and race in a polyamorous relationship. At the same time uncovering physical traces of her ancestor and searching for the small boy Juan he brought back to France with him.

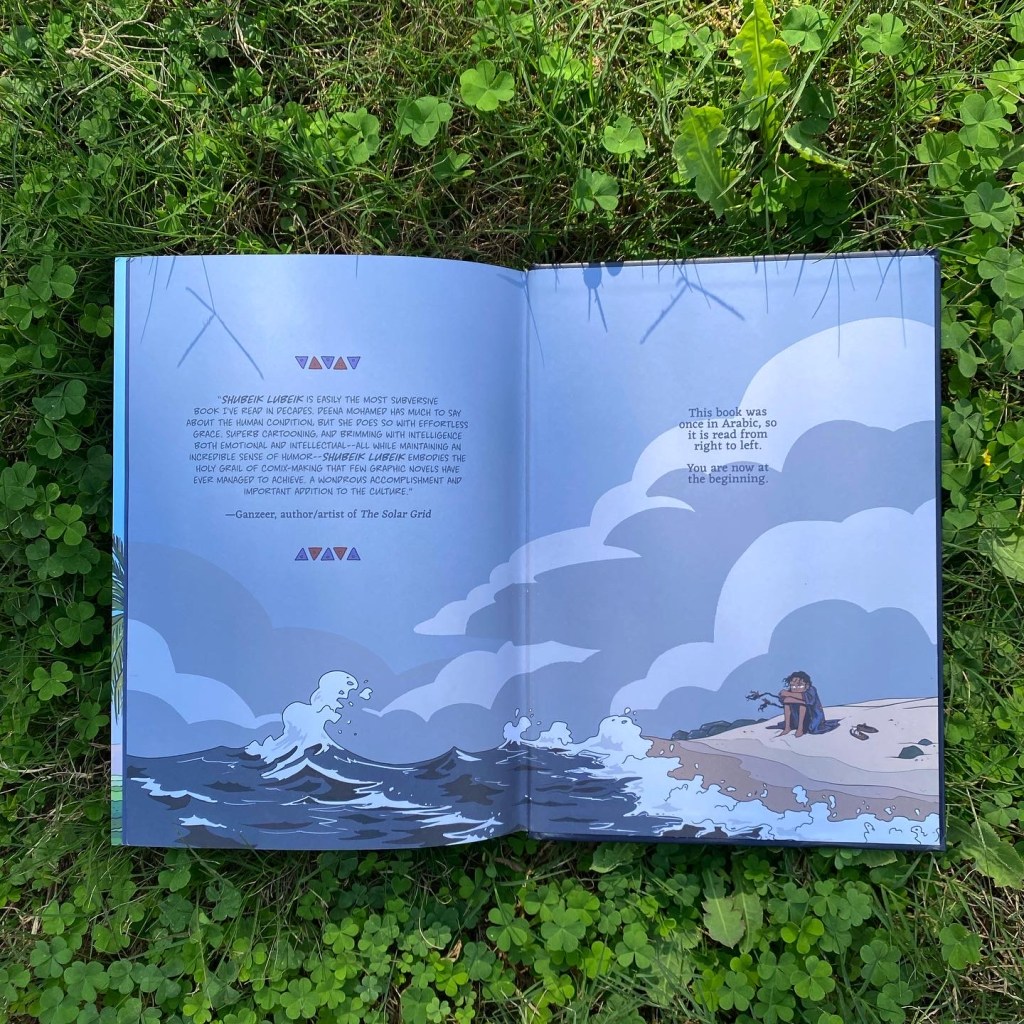

Juan isn’t a ceramic piece rescued from the rubble, nor is he made of gold or silver; he isn’t even a shrivelled child mummy destined for a museum far away from the volcanoes. Yet he crosses the pond as the adventurer’s property. Juan is just another of Wiener’s small contributions to the transformation of the European concept of history. He is part of Wiener’s “expedition,” which is not like that of conquistadors or pioneers but like those of other scientific travellers who sought to “reignite the Incan sun, brutally extinguished by the Spanish cross.”

I was totally captivated by this narrative from start to finish. Each sentence and paragraph so carefully constructed, I often went back and reread them, because they often articulated something that asked to be considered.

I had read a few reviews that criticised the attention she gave to herself, but I didn’t feel as if this was done without context. It is a work of autofiction and the author puts herself as much under the spotlight as her ancestor, she is self aware and critical of her own behaviours, she exposes them and puts them on public display to be judged.

Wiener really is a fluid narrator, a chronicler of minor details and excesses, the kind of storyteller who knows when to set aside principles and literary convention for the sake of hooking his readers, who doesn’t think twice before using whatever’s within reach to spice up his adventures, changing the rules of the game in a context where he really shouldn’t be taking it that far. He is also, without a doubt, the creator of the story’s hero: himself. Had he lived in the twenty-first century, he might have been accused of the worst possible crime an author can be accused of today: writing autofiction.

Broken Memories, Finding Reparation

Towards the end she seeks help or healing and her solution is to join a group called ‘Decolonizing My Desire’. She reaches out to a researcher for help about the ancestor, but finds that invalidating.

Ultimately it is her imagination and poetry that perhaps provides her with answers, the blank page that she is capable of filling, the stories she is able to create, the endings she can provide herself. She controls the narrative, no one else does.

Undiscovered is a well researched inquisition of family and colonial history, ancestral threads and both modern and ancient cultural connections that reflects one woman’s attempt to better understand herself for the benefit of her close relationships. It is about looking at personal and cultural wounds and creating solutions that help a person to move forward.

Further Reading

Read An Extract From the Book: Undiscovered by Gabriela Wiener

New York Times: Gabriela Wiener Does Not Care if You Don’t See Her Writing as Literature By María Sánchez Díez Oct 2023

Electric Lit: Gabriela Wiener Challenges the White Man in Her Head an interview by JR Ramakrishnan Oct 2023

In the interview, Wiener is asked about her surname growing up:

In countries that suffered colonization, both racism and classism from white creole elites towards people of Andean descent is virulent and normalized. Brown or “huaco” faces are penalized but so are brown surnames. And if you already have both you’re screwed. I used to be terrified of going on class trips to archeology museums because we would always pass by a huaco display and the kids would make fun of me, comparing my face to the huaco portraits. But at the same time my last name whitened me, protected me, it was my link to whiteness.

2018 Exposition Musée Quai Branly: « Le Pérou avant les Incas » au musée du Quai Branly

My Review of Ancestor Trouble; A Reckoning and A Reconciliation by Maud Newton

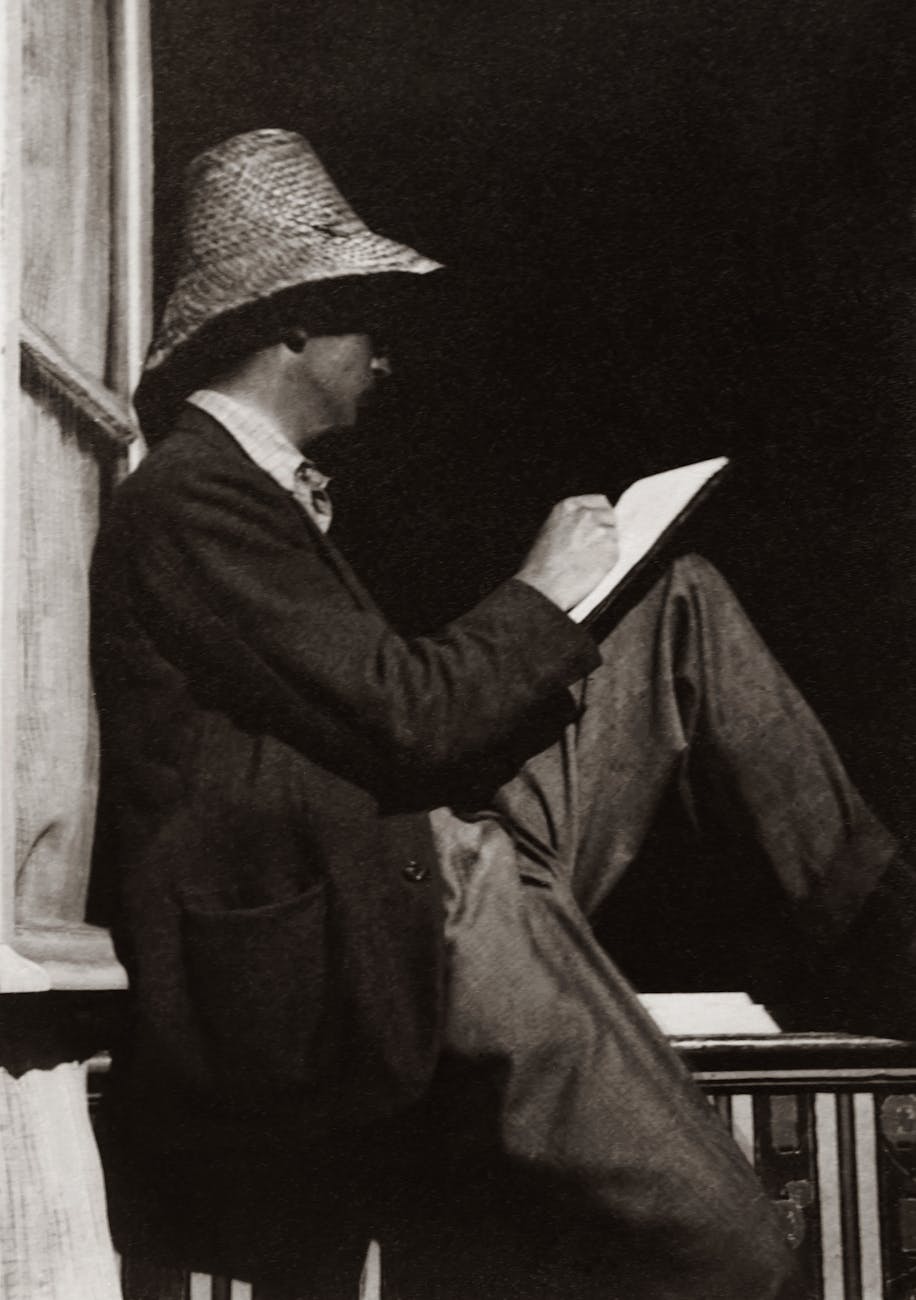

Author, Gabriela Wiener

Gabriela Wiener is a Peruvian writer and journalist based in Madrid, Spain. Her books include Nine Moons, a memoir on pregnancy and reproduction, and Sexographies, a collection of first person gonzo journalism essays on contemporary sex culture, swingers clubs and ayahuascha.

Her work has appeared in numerous publications and has been translated into six languages. She is a regular contributor to El Público (Spain), Vice and New York Times en Español. Wiener won Peru’s National Journalism Award for her investigative report on violence against women.