The Dublin Literary Award has announced a longlist of 70 books nominated by 80 libraries from 35 countries around the world.

Celebrating excellence in world literature and now in its 29th year, this award is the world’s most valuable annual prize for a single work of fiction published in English, worth €100,000 to the winner.

The list features 16 debut novelists and 31 novels in translation representing 14 languages including Finnish, Hungarian, Romanian, Serbian and Turkish. New Zealand author Catherine Chidgey has been nominated for two novels.

The shortlist will be revealed on 26th March 2024 and the winner will be announced on 23rd May 2024.

The nominated novels will be available for readers to borrow from Dublin City Libraries and from public libraries around Ireland, and some can be borrowed as eBooks and eAudiobooks on the free Borrowbox app, available to all public library users.

I have read Pet, Birnam Wood, Soldier Sailor, Old God’s Time and Demon Copperhead.

The Longlist

1000 coils of fear by Olivia Wenzel (Germany) tr. Priscilla Layne – A multilayered and rhythmic debut novel about her life as a Black German woman living in Berlin and New York during the chaos of the 2016 U.S. presidential election from playwright Olivia Wenzel.

A History of the Island by Eugene Vodolazkin (Russia) tr. Lisa C. Hayden – Internationally acclaimed novelist and scholar of medieval literature, Eugene Vodolazkin returns with a satirical parable about European and Russian history, the myth of progress, and the futility of war.

A Minor Chorus by Billy-Ray Belcourt (Canada) – An urgent first novel about breaching the prisons we live inside from one of Canada’s most daring literary talents. An unnamed narrator abandons grad school and returns to northern Alberta in search of answers to existential questions about family, love, and happiness. What ensues is a series of conversations amounting to an autobiography of his hometown.

Ada’s Realm by Sharon Dodua Otoo (Germany) tr. Jon Cho-Polizzi – In a small village in what will become Ghana, Ada gives birth to a baby who does not live. As she grieves for her child, Portuguese traders arrive in the village, an event that will bear terrible repercussions for Ada and her kin. Centuries later, Ada will become the mathematician Ada Lovelace; Ada, a prisoner forced into prostitution in a concentration camp; and Ada, a pregnant Ghanaian woman who arrives in Berlin in 2019 for a fresh start. Ada is not one woman, but many, and she is all women. This debut from Sharon Dodua Otoo paints an astonishing picture of femininity and resilience with deep empathy and infinite imagination.

An Astronomer in Love by Antoine Laurain (France) tr. by Louise Rogers Lalaurie & Megan Jones – Part swashbuckling adventure on the high seas and part modern-day love story set in the heart of Paris, An Astronomer in Love is an enchanting tale of adventure, destiny and the power of love.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton (New Zealand) – A landslide has closed the Korowai Pass cutting off the town of Thorndike, leaving a farm abandoned. The disaster presents an opportunity for Birnam Wood, a guerrilla gardening collective that plants crops where no one will notice. An enigmatic billionaire also has an interest in the place. Can they trust him? Can they trust each other? A propulsive literary thriller from the Booker Prize-winning author of The Luminaries, Birnam Wood is a brilliantly constructed tale of intentions, actions, consequences and survival.

Breakwater by Marijke Schermer (Netherlands) tr.(Dutch) Liz Waters – A woman who seems to have it all is unable to tell her husband of her violent secret past, which threatens to tear their family apart. “A secret between a husband and a wife threatens their existence in Marijke Schermer’s novel Breakwater. Breakwater is a concise, cutting story about trauma, post-traumatic stress, and misdirected love.”

Canción by Eduardo Halfon (Guatemala) tr. (Spanish) Lisa Dillman & Daniel Hahn – In Canción, Eduardo Halfon’s eponymous wanderer is invited to a Lebanese writers’ conference in Japan, where he reflects on his Jewish grandfather’s multifaceted identity. To understand more about the day in January 1967 when his grandfather was abducted by Guatemalan guerillas, Halfon searches his childhood memories. Soon, chance encounters around the world lead to more clues about his grandfather’s captors, including a butcher nicknamed “Canción” (or song). As a brutal and complex history emerges against the backdrop of the Guatemalan Civil War, Halfon finds echoes in the stories of a woman he meets in Japan whose grandfather survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Chain-Gang All-Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah (US) – Two top women gladiators fight for their freedom within a depraved private prison system not so far-removed from America’s own. In packed arenas, live-streamed by millions, prisoners compete as gladiators for the ultimate prize: their freedom. Fan favourites Loretta Thurwar & Hamara ‘Hurricane Staxxx’ Stacker are teammates and lovers. Thurwar is nearing the end of her time on the circuit, free in just a few matches, a fact she carries as heavily as her lethal hammer. As she prepares for her final encounters, as protestors gather at the gates, and as the programme’s corporate owners stack the odds against her – will the price be simply too high?

Crimson Spring by Navtej Sarna (India) – On 13 April 1919, around 25,000 unarmed Indians had gathered in Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar. Many were listening to speakers denouncing the Rowlatt Act, while others were there to relax. In the evening, a detachment of soldiers led by Brigadier General R. E. H. Dyer entered the Bagh and open fired without warning. Several hundred perished and several hundred more were injured. Navtej Sarna brings the horror of the atrocity to life through the eyes of nine characters -Indians and Britons, ordinary people and powerful officials, the innocent and the guilty. Set against India’s epic freedom struggle, the book is a powerful, unsettling meditation on the costs of colonialism.

Crooked Plow by Itamar Vieira Junior (Brazil) tr.(Brazilian Portuguese) Johnny Lorenz – Deep in Brazil’s neglected Bahia hinterland, two sisters find an ancient knife beneath their grandmother’s bed and, momentarily mystified by its power, decide to taste its metal. The shuddering violence that follows marks their lives and binds them together forever.

Heralded as a new masterpiece and the most important Brazilian novel of this century, this fascinating and gripping story about the lives of subsistence farmers in the Brazil’s poorest region, three generations after the abolition of slavery in that country is at once fantastic and realist, covering themes of family, spirituality, slavery and its aftermath and political struggle.

Dandelion Daughter by Gabrielle Boulianne-Tremblay (Canada) tr. Eli Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch (French) – An intimate portrait of growing up having been assigned the wrong sex at birth. Set against the windswept countryside of the remote Charlevoix region north of Montreal, an autobiographical novel immortalizes her early years as an alienated boy trapped in a world of small-town values. In the midst of her parents’ dissolving marriage, Boulianne-Tremblay traverses complex adolescent years of self-discovery and first loves, to harrowing episodes that fuel the growing realization that she must transition and give birth to her new self if she is to continue living at all. One of the first novels of its kind to appear in Quebec.

Day’s End by Garry Disher (Australia) – Hirsch’s rural beat is wide. Daybreak to day’s end, dirt roads and dust. Every problem that besets small towns and isolated properties, from unlicensed driving to arson. Today he’s driving an international visitor around: Janne Van Sant, whose backpacker son went missing while the borders were closed. They’re checking out his last photo site, his last employer. A feeling that the stories don’t quite add up. A call comes in: a roadside fire. Nothing much—a suitcase soaked in diesel and set alight. Two noteworthy facts emerge. Janne knows more than Hirsch about forensic evidence. And the body in the suitcase is not her son’s.

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (US) – Demon’s story begins with his traumatic birth to a single mother in a single-wide trailer. For the life ahead of him he would need all of that fighting spirit, a quick wit, and some unexpected talents. In the southern Appalachian Mountains of Virginia, poverty and addiction are as natural as the grass grows. For Demon, born on the wrong side of luck, the affection and safety he craves is as remote as the ocean he dreams of seeing one day.

Falling Hour by Geoffrey Morrison (Canada) – It’s a hot summer day, and Hugh Dalgarno, a 31-year-old clerical worker, thinks his brain is broken. Over the course of several hours in an uncannily depopulated public park, he will traverse the baroque landscape of his own thoughts: the theology of nosiness, the beauty of the arbutus tree, the theory of quantum immortality, Louis Riel’s letter to an Irish newspaper, the baleful influence of Calvinism on the Scottish working class, the sea, and, ultimately, thinking itself and how it may be represented in writing. A meandering sojourn, as if the history-haunted landscapes of Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn were shrunk down to a mere 85 acres.

Feast by Emily O’Grady (Australia) – Alison is an actress who no longer acts, Patrick a musician past his prime. The eccentric couple live an isolated existence in Scotland until Patrick’s teenage daughter Neve, flees Australia to spend a year abroad with her father, and the stepmother she barely knows.

On the weekend of Neve’s eighteenth birthday, her father insists on a special feast to mark her coming of age. Despite Neve’s objections, her mother Shannon arrives in Scotland to join the celebrations. What none of them know is that Shannon has arrived with a hidden agenda that has the potential to shatter the delicate façade of the loving, if dysfunctional, family.

Hades by Aisha Zaidal (Malaysia) – In 2012, sixteen-year-old troublemaker Kei and his mother move into a decaying low-cost flat from the slums at the edge of town, right next to Maryam, a young mother, and her three-year-old son Ishak. Shunned by society, Kei and Maryam develop an unspoken bond, which starts to fray as the ghosts of their pasts circle in. Both wonder if they can free themselves of the men who made them the abominations everyone considers them to be, and of the despair creeping in around them.

Haven by Emma Donoghue (Ireland) – In 7th-century Ireland, a scholar/priest called Artt has a dream telling him to leave the sinful world behind. Taking two monks – young Trian & old Cormac – he rows down the river Shannon in search of an isolated spot on which to found a monastery. With only faith to guide them and drifting out into the Atlantic, the three men find a steep, bare island, inhabited by tens of thousands of birds, and claim it for God. In such a place, what will survival mean? What they find is the extraordinary island now known as Skellig Michael.

Hello Beautiful by Ann Napolitano (US) –

The four Padavano girls bring loving chaos to their neighbourhood. William Waters grew up in a house silenced by tragedy. When he meets Julia Padavano, it’s as if the world has lit up around him. With Julia comes her family: Sylvie, the dreamer; Cecelia, the artist; and Emeline patiently taking care of them all. But when darkness from William’s past begins to block the light of his future, a catastrophic rift leaves the family inhabiting two sides of a fault line. Can they find their way back to each other? Can love make a broken family whole?

Hollow Bamboo: A Novel by William Ping (Canada) – The hilarious and heart-breaking story of two William Pings in Newfoundland—the lost millennial and the grandfather he knows nothing about. Based on a true story, Hollow Bamboo recounts with humour and sympathy the often-brutal struggles, and occasional successes, faced by some of the first Chinese immigrants in Newfoundland. Drawing on elements of magical realism, auto fiction and satire, as well as deep historical research, Hollow Bamboo is a fresh and original portrayal of our past and our present, and the debut of an extraordinary new author.

Human Nature by Serge Joncour (France) tr. Louise Rogers Lalaurie – When his three sisters escape to the city Alexander is left to run the family farm. Though reluctant, he commits himself to honouring the traditional methods that prioritise the welfare of his cattle, and produce the highest quality meat. But the world around him is changing. The insatiable appetites of supermarkets and fast food chains demand that standards must be sacrificed for speed. As Alexandre struggles to balance his principles and his livelihood, he is drawn to the beautiful Constanze, part of a group of environmental activists keen to draw him into their cause. Farmers uses ammonium nitrate and so do eco-terrorists…

Identitti by Mithu Sanyal (Germany) tr. Alta L. Price – Nivedita (a.k.a. Identitti), a doctoral student who blogs about race with the help of Hindu goddess Kali, is in awe of Saraswati, her superstar postcolonial and race studies professor. But Nivedita’s life and sense of self are upturned when it emerges that Saraswati is actually white. Hours before she learns the truth Nivedita praises her tutor in a radio interview, which calls into question her own reputation and ignites an angry backlash among her peers and online community. A darkly comedic tour de force, Identitti showcases the outsized power of social media in the current debates around identity politics and the power of claiming your own voice.

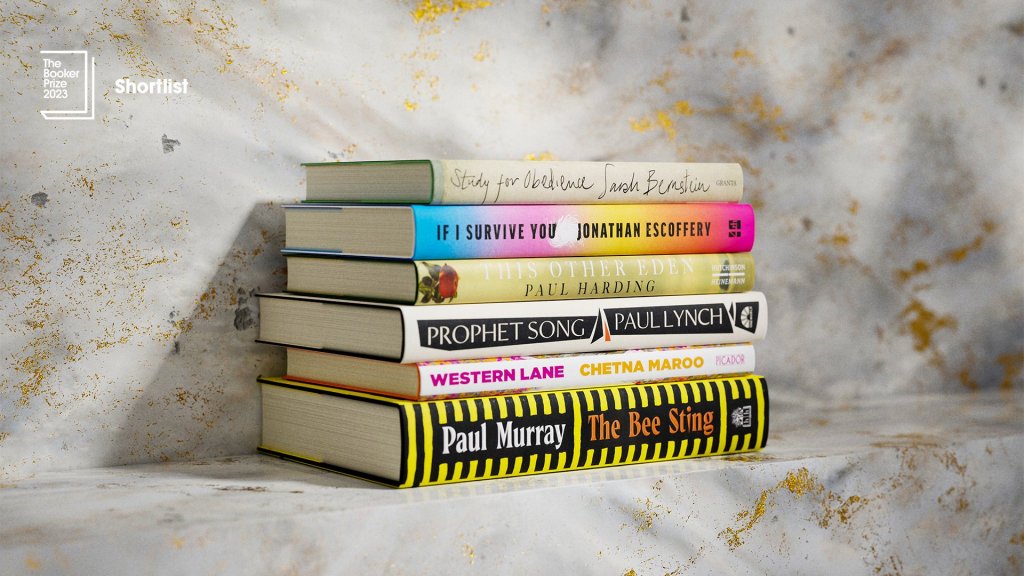

If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery (US) – In the 1970s, Topper and Sanya flee to Miami as political violence consumes their native Kingston. But America, as the couple and their two children learn, is far from the promised land. Excluded from society as Black immigrants, the family pushes on first through Hurricane Andrew and later the 2008 recession. But even as things fall apart, the family remains motivated by what their younger son calls “the exquisite, racking compulsion to survive.” Pulsing with vibrant lyricism and sly commentary, Escoffery’s debut unravels what it means to be in between homes and cultures in a world at the mercy of capitalism and white supremacy.

Limberlost by Robbie Arnott (Australia) – In the heat of a long summer Ned hunts rabbits in a river valley, hoping the pelts will earn him enough money to buy a small boat. His two brothers are away at war, their whereabouts unknown. His father and older sister struggle to hold things together on the family orchard, Limberlost. Desperate to ignore it all—to avoid the future rushing towards him—Ned dreams of open water. As his story unfolds over the following decades, we see how Ned’s choices that summer come to shape the course of his life, the fate of his family and the future of the valley, with its seasons of death and rebirth.

Lone Women by Victor LaValle (US) – Adelaide Henry carries an enormous locked steamer trunk with her wherever she goes. It’s locked because when the trunk opens, people around Adelaide disappear. It’s 1915 and Adelaide is in trouble. Her secret has killed her parents, forcing her to flee California for a new life in Montana. Dragging the trunk with her, she becomes one of the “lone women,” accepting the government’s offer of free land for those who can tame it—except Adelaide isn’t alone. And the secret she’s kept locked away might be the key to her survival.

Memorial, 29 June by Tine Høeg (Denmark) tr. Misha Hoekstra – Celebrated for her signature insight and precision, Tine Høeg returns with a wry, haunting, and riotously funny novel about how loss is bound up with the urge to create. Asta is invited to a memorial. It’s been ten years since her university friend August died. The invitation disrupts everything – the novel she is working on, her friendship with Mai and her two-year-old son – reanimating longings, doubts, and the ghosts of parties past. Moving between Asta’s past and present, Memorial, 29 June is a novel about who we really are, and who we thought we would become.

Monsters Like Us by Ulrike Almut Sandig (Germany) tr. Karen Leeder – the story of old friends Ruth and Viktor in the last days of Communist East Germany. Inseparable since kindergarten, forced to go their different ways to escape their difficult childhood: Ruth into music and the life of a professional musician; Viktor into violence and a neo-Nazi gang. A story of families, a story of abuse, a story about the search for redemption and the ways it takes shape over generations. More than anything, it is about the stories we tell ourselves about who we are, and who we want to be.

My Father’s House by Joseph O’Connor (Ireland) – September 1943: German forces occupy Rome. SS officer Paul Hauptmann rules with terror. An Irish priest, Hugh O’Flaherty, dedicates himself to helping those escaping from the Nazis. His home is Vatican City, the world’s smallest state, a neutral country within Rome where the occupiers hold no sway. Here Hugh brings together an unlikely band of friends to hide the vulnerable under the noses of the enemy. But Hauptmann’s net begins closing in on the Escape Line and the need for a terrifyingly audacious mission grows critical. Based on an extraordinary true story, My Father’s House is a powerful literary thriller from a master of historical fiction.

My Men by Victoria Kielland (Norway) tr. Damion Searls – Based on the true story of Norwegian maid turned Midwestern farmwife Belle Gunness, the first female serial killer in American history, My Men is the radically empathetic and disquieting portrait of a woman capable of ecstatic love and gruesome cruelty. Among thousands of other Norwegian immigrants seeking freedom, Brynhild Størset emigrated to the American Upper Midwest in the late nineteenth century, changing her name and her life. As Bella, later Belle Gunness, she came in search of fortune and faith but, most of all, love. In pursuit of her American Dream, Kielland’s Belle grows increasingly alienated, ruthless, and perversely compelling.

Now I Am Here by Chidi Ibere (UK) – About to make his last stand, a soldier facing certain death at enemy hands, writes home to his love to explain how he ended up there. The Officer in the story has no name nor is his nation specified. While out walking, he stumbles upon officers enjoying a military barbecue and is persuaded to join them. He enjoys the comradeship of the event, is quickly seduced by the smart, tailored military uniform he is fitted with, by the power bestowed upon it and the respect commanded by it. From there, this gentle man is gradually transformed into a war criminal, committing acts he wouldn’t have thought himself capable.

Old God’s Time by Sebastian Barry (Ireland) – Retired policeman Tom Kettle is enjoying the quiet of his new home in Dalkey, overlooking the sea. His peace is interrupted when two former colleagues turn up at his door to ask about a traumatic, decades-old case. A case that Tom never came to terms with. His peace is further disturbed by a young mother who asks for his help. And what of Tom’s wife, June, and their two children? A beautiful, haunting novel about what we live through, what we live with, and what will survive of us.

Open Heart by Elvira Lindo(Spain) tr. Adrian Nathan West – This intimate family novel that follows the rise and fall of a great love is also a moving tribute to the generation that struggled to survive in Spain after the Civil War. In Open Heart, Elvira Lindo tells the story of her parents—the story of an excessive love, passionate and unstable, forged through countless fights and reconciliations, which had a profound effect on their entire family.

Orgy by Gábor Zoltán (Hungary) tr. Thomas Sneddon – A nightmarish recounting of events from the final phase of the Holocaust in Hungary. In late 1944 and early 1945 Budapest was consigned to the rule of the fascist organization known as the Arrow Cross. They sought out individuals not only of Jewish descent but anyone they viewed as liberals, “English sympathizers” or “humanists.” One such man is the novel’s main character, the thirty-year-old factory owner, Renner. He is a successful, fearless man: the Arrow Cross have plenty of reasons to kill him. But instead of a swift execution, they torture and humiliate him even longer than usual, subsequently forcing him to assist them.

Our Missing Hearts by Celeste Ng (US) – Bird Gardner lives a quiet existence with his father, a former linguist who now shelves books in a library. His mother Margaret, a Chinese American poet, left without a trace. He doesn’t know what happened to her—only that her books have been banned. Bird receives a letter containing a cryptic drawing, and he’s entered a quest to find her. His journey will take him to the folktales she poured into his head as a child, through the ranks of an underground network of heroic librarians, and finally to NYC, where he will finally learn the truth about what happened to his mother, and what the future holds for them both.

Our Share of Night by Mariana Enriquez (Argentina) tr. Megan McDowell (Spanish) – Moving back and forth in time, from London in the swinging 1960s to the brutal years of Argentina’s military dictatorship and its turbulent aftermath, Our Share of Night is a novel like no other: a family story, a ghost story, a story of the occult and the supernatural, a book about the complexities of love and longing with queer subplots and themes. This is the masterwork of one of Latin America’s most original novelists, “a mesmerizing writer,” says Dave Eggers, “who demands to be read.”

Pet by Catherine Chidgey (New Zealand) – Like every other girl in her class, twelve-year-old Justine is drawn to her glamorous, charismatic new teacher, and longs to be her pet. However, when a thief begins to target the school, Justine’s sense that something isn’t quite right grows ever stronger. With each twist of the plot, this gripping story of deception and the corrosive power of guilt takes a yet darker turn. Young as she is, Justine must decide where her loyalties lie.

Praiseworthy by Alexis Wright (Australia) – In a small town in northern Australia dominated by a haze cloud, a crazed visionary sees donkeys as the solution to the global climate crisis and the economic dependency of the Aboriginal people. His wife seeks solace from his madness in the dance of moths and butterflies. One of their sons, called Aboriginal Sovereignty, is determined to commit suicide. The other, Tommyhawk, wishes his brother dead so that he can pursue his dream of becoming white and powerful. Praiseworthy is a novel which pushes allegory and language to its limits, a cry of outrage against oppression and disadvantage, and a fable for the end of days.

Properties of thirst : a novel by Marianne Wiggins (US) – “Rocky” Rhodes has spent years fiercely protecting his California ranch from the LA Water Corporation. It is where he and his wife Lou raised their twins, Sunny and Stryker, and it where Rocky has mourned Lou since her death. When the government decides to build an internment camp next to the ranch, Rocky realizes that the land faces even bigger threats than the LA watermen. Complicating matters is the fact that the Department of the Interior man assigned to build the camp, who only begins to understand the horror of his task after it may be too late, becomes infatuated with Sunny and entangled with the Rhodes family.

Querelle of Roberval: A Syndical Fiction by Kevin Lambert (Canada) tr. Donald Winkler (French) – As a millworkers’ strike in the northern lumber town of Roberval drags on, tensions escalate between the workers—but when a lockout renews their solidarity, they rally around the mysterious and magnetic influence of Querelle, a dashing newcomer from Montreal. As the dispute hardens and both sides refuse to yield, the tinderbox of class struggle and entitlement ignites in a firestorm of passions carnal and violent. A tribute to Jean Genet’s antihero, and a brilliant reimagining of the ancient form of tragedy, Querelle of Roberval is a wildly imaginative story of justice, passion, and murderous revenge.

River Sing Me Home by Eleanor Shearer (UK) – Rachel is searching for her children. For Mary Grace, Micah, Thomas Augustus, Cherry Jane and Mercy. These are the five who were sold to other plantations; the faces she cannot forget. It is 1834, and the law says her people are now free. But for Rachel freedom means finding her children. With fear snapping at her heels, Rachel keeps moving. From sunrise to sunset, through the cane fields of Barbados to the forests of British Guiana, then on to Trinidad, up the dangerous river and to the open sea. Only once she knows their stories can she rest. Only then can she finally find home…

Rombo by Esther Kinsky (Germany) tr. Caroline Schmidt – In May and September 1976, two earthquakes ripped through north-eastern Italy, causing severe damage to the landscape and its population. About a thousand people died under the rubble, tens of thousands were left without shelter, and many ended up leaving their homes in Friuli forever. In Rombo, Esther Kinsky’s sublime new novel, seven inhabitants of a remote mountain village talk about their lives, which have been deeply impacted by the earthquake that has left marks they are slowly learning to name. From the shared experience of fear and loss, the threads of individual memory soon unravel and become haunting and moving narratives of a deep trauma.

Schmutz by Felicia Berliner (US) – In this witty, provocative, and “compulsively readable coming-of-age story” (Cosmopolitan), a young Hasidic woman on a quest to get married fears she will never find a groom because of her secret addiction to porn. Like the other women in her ultra-Orthodox community, Raizl expects to find a husband through arranged marriage. But Raizl has a secret. With a hidden computer to help her complete her college degree, she falls down the slippery slope of online pornography. As Raizl dives deeper into the world of porn at night, her daytime life begins to unravel. Raizl must balance her growing understanding of her sexuality with the expectations of the family she loves.

Small Mercies by Denis Lehane (US) – In the summer of 1974 a heatwave blankets Boston and Mary Pat Fennessey is trying to stay one step ahead of the bill collectors. One night Mary Pat’s teenage daughter Jules stays out late and doesn’t come home. That same evening, a young Black man is found dead, struck by a subway train under mysterious circumstances. The two events seem unconnected. But Mary Pat, propelled by a desperate search for her missing daughter, begins turning over stones best left untouched – asking questions that bother Marty Butler, chieftain of the Irish mob, and the men who work for him, men who don’t take kindly to any threat to their business.

Solider Sailor by Claire Kilroy (Ireland) – In her wildly acclaimed novel, her first in over a decade, Claire Kilroy creates an unforgettable heroine whose fierce love for her young son clashes with the seismic change to her own identity. As her marriage strains, and she struggles with questions of autonomy, creativity and the passing of time, an old friend makes a welcome return – but can he really offer a lifeline to the woman she used to be?

Solenoid by Mircea Cărtărescu (Romania) tr. Sean Cotter – Based on Cărtărescu’s own role as a high school teacher, Solenoid begins with the mundane details of a diarist’s life and spirals into a philosophical account of life, history, philosophy, and mathematics. On a broad scale, the novel’s investigations of other universes, dimensions, and timelines reconcile the realms of life and art. Grounded in the reality of late 1970s/early 1980s Communist Romania, including long lines for groceries, the absurdities of the education system, and the misery of family life. Combining fiction, autobiography and history, Solenoid ruminates on the exchanges possible between the alternate dimensions of life and art within the Communist present.

Stolen by Ann-Helén Laestadius (Sweden) tr. Rachel Willson-Broyles – Nine-year-old Elsa lives just north of the Arctic Circle. She and her family are Sámi, Scandinavia’s indigenous people, and make their living herding reindeer. One morning, Elsa witnesses a man brutally killing her reindeer calf. She recognises the man but refuses to tell anyone – least of all the Swedish police force – about what she saw. A decade later, Elsa finds herself the target of the man she first encountered all those years ago, and something inside of her finally breaks. The guilt, fear and anger she’s been carrying since childhood come crashing over her like an avalanche, and will lead Elsa to a final catastrophic confrontation.

Stone and Shadow by Burhan Sönmez (Turkey) tr. Alexander Dawe – In the city of Mardin, the orphaned Avdo finds purpose when an old mason takes him on as an apprentice. From Master Josef, he learns the importance of their art, which looks after the dead and bears witness to their lives. Avdo travels the country and meets a woman he loves wholeheartedly, only to lose her through a tragic crime. Resigned to a lonely existence, he retreats from the world into his cemetery workshop, but even there, life, with all its sorrows, joys, injustices, and gifts, draws him in unexpected directions.

Take What You Need by Idra Novey (US) – Take What You Need traces the parallel lives of Jean and her beloved but estranged stepdaughter, Leah, who’s sought a clean break from her rural childhood. In Leah’s urban life with her young family, she’s revealed little about Jean, how much she misses her stepmother’s hard-won insights and joyful lack of inhibition. But with Jean’s death, Leah must return to sort through what’s been left behind. Set in the Allegheny Mountains of Appalachia, the novel explores the continuing mystery of the people we love most, zeroing in on the joys and difficulties of family with great verve.

The Ascent by Stefan Hertmans (Netherlands) tr. David McKay (Dutch) – In 1979, Stefan Hertmans fell in love with a beautiful old house in Ghent in Belgium, which he lovingly rescued from decay. Now, years later, he learns that a bust of Hitler once sat on the mantelpiece, and a war criminal relaxed in its rooms with his family. This shocking discovery sends Hertmans off to the archives and to interview next of kin, to uncover the secrets of the house and expose the atrocities this man committed. A story of war, family, and fate, Hertmans masterfully brings history to life, as he appears in the novel as a trusted guide, and imagines individual lives to tell the greater European story.

The Axeman’s Carnival by Catherine Chidgey (New Zealand) – Everywhere, the birds: sparrows and skylarks and thrushes, starlings and bellbirds, fantails and pipits – but above them all and louder, the magpies. We are here and this is our tree and we’re staying and it is ours and you need to leave and now.

The Birthday Party by Laurent Mauvignier (France) tr. Daniel Levin Becker – Buried deep in rural France, little remains of the isolated hamlet of the Three Lone Girls, save a few houses and a curiously assembled quartet. While Patrice plans a surprise for his wife’s 40th birthday, inexplicable events start to disrupt the hamlet’s quiet existence. Told in rhythmic, propulsive prose that weaves seamlessly from one consciousness to the next, a deft unravelling of the stories we hide from others and from ourselves, a gripping tale of the violent irruptions of the past into the present, written by a major contemporary French writer.

The Chinese Groove by Kathryn Ma (US) – Eighteen-year-old Shelley, born into a much-despised branch of the Zheng family in Yunnan Province, heads to San Francisco to claim his destiny, confident that any hurdles will be easily overcome. Shelley is dismayed to find that his “rich uncle” is his unemployed second cousin and that the guest room he’d envisioned is but a scratchy sofa. Even worse, the loving family he hoped would embrace him is in shambles, shattered by a senseless tragedy that has cleaved the family in two. Ever the optimist, Shelley concocts a plan to resuscitate his American dream by insinuating himself into the family.

The Crane Husband by Kelly Barnhill (US) – In this stunning contemporary retelling of “The Crane Wife” by the Newbery Medal-winning author of The Girl Who Drank the Moon, one fiercely pragmatic teen forced to grow up faster than was fair will do whatever it takes to protect her family—and change the story.

The Drinker of Horizons by Mia Couto (Mozambique) tr. David Brookshaw (Portuguese) – the epic love story between a young Mozambican woman named Imani and the Portuguese sergeant Germano de Melo to its moving close. We resume where The Sword and the Spear concluded: While Germano is left behind in Africa, serving with the Portuguese military, Imani has been enlisted to act as the interpreter to the imprisoned emperor of Gaza, Ngungunyane, on the long voyage to Lisbon. For the emperor and his seven wives, it will be a journey of no return. Imani’s own return will come only after a decade-long odyssey through the Portuguese empire at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The Exhibition by Miodrag Kajtez (Serbia) tr. Nikola M. Kajtez – Izlozba (original title of The Exhibition published in 2015 and awarded the National Award Laza Kostić for the book of the year) is an explicit story about the morphology of death. The characters seem to be as if from the other side of life. On the other hand, the very text of the novel is addictively fun, especially for literary connoisseurs, the humor, although unobtrusive, is often hilarious.

The Eye of the Beholder by Margie Orford (South Africa) – Cora carries secrets her daughter can’t know. Freya is frightened by what her mother leaves unsaid. Angel will only bury the past if it means putting her abusers into the ground.

One act of violence sets the three women on a collision course, each desperate to find the truth. In a nail-biting thriller set between the scorched red soil of South Africa, the pitiless snowfields of Canada and the chilly lochsides of western Scotland, each woman must contend with the spectres of male violence, sexual abuse and the choices we each make to keep our souls.

The Fire by Daniela Krien (Germany) tr. Jamie Bulloch – With plans adrift after a fire burns down their rented holiday cabin, Rahel and Peter find themselves on an isolated farm where Rahel spent many a happy childhood summer. Suddenly, after years of navigating careers, demanding children and the monotony of the daily routine, they find themselves unable to escape each other’s company. With three weeks stretching ahead, they must come to an understanding on whether they have a future together. What happens when love grows older and passion has faded? When what divides us is greater than what brought us together? And how easy is it to ask the fundamental questions about our relationships?

The Ghetto Within by Santiago H. Amigorena (Argentina/France) tr. Frank Wynne – The Ghetto Within re-imagines the life of its author’s Jewish grandfather whose guilt provokes an enduring silence to span generations. 1928. Vicente Rosenberg is a European émigré starting a new life in Buenos Aires. Despite success, Vicente still misses his mother, who stayed behind in Poland. For years, she writes him. Yet, as unnerving rumors mount from abroad, her letters become increasingly sporadic, and Vicente begins to construct the reality of a tragedy that already occurred. Then, one day, the letters cease. Racked with guilt, Vicente lapses into a longstanding silence. With his new novel, Amigorena finds the language to retrieve his voice from the oblivion of familial trauma.

The Great Reclamation by Rachel Heng (Singapore) – On a quiet moonlit night, Ah Boon, young and terrified, takes his first trip out to sea in his father’s fishing boat – a rite of passage for the boys of the kampong. As the air hums and the wind howls, a mysterious, impossible island materialises in the darkness; an island that Ah Boon soon learns only he has the ability to find. But this is only the beginning of the story, and as Ah Boon grows up, alongside Siok Mei, the spirited girl he has fallen in love with, he finds himself caught in the tragic sweep of Singapore’s history.

The House of Fortune by Jessie Burton (UK) – In the golden city of Amsterdam, in 1705, Thea Brandt is turning eighteen, and she is ready to welcome adulthood with open arms. At the city’s theatre, Walter, the love of her life, awaits her, but at home in the house on the Herengracht, all is not well – her father Otto and Aunt Nella argue endlessly, and the Brandt family are selling their furniture in order to eat. On Thea’s birthday, also the day that her mother Marin died, the secrets from the past begin to overwhelm the present.

The Moonday Letters by Emmi Itäranta (Finland) tr.Emmi Itäranta – Sol has disappeared. Their Earth-born wife Lumi sets out to find them but it is no simple feat: each clue uncovers another enigma. Their disappearance leads back to underground environmental groups and a web of mystery that spans the space between the planets themselves. Told through letters and extracts, the course of Lumi’s journey takes her not only from the affluent colonies of Mars to the devastated remnants of Earth, but into the hidden depths of Sol’s past and the long-forgotten secrets of her own. Part space-age epistolary, part eco-thriller, and a love story between two individuals from very different worlds.

The Orphans of Amsterdam by Elle Van Rijn (Netherlands) tr. Jai van Essen – Amsterdam, 1941. My hands are so shaky I’m fumbling. Where to hide? I pull open the dresser, throw aside the blankets, put the baby in and push the drawer shut, just as the nursery door swings open. The German officer marches into the room, yelling over the crying downstairs: ‘You! Grab all the children – now!’ Based on the heart-wrenching true story of an ordinary young woman who risked everything to save countless children from the Nazis, this gripping read is perfect for fans of The Tattooist of Auschwitz, We Were the Lucky Ones and The Nightingale.

The Sleeping Car Porter by Suzette Mayr (Canada) – It’s 1929, and Baxter is considered lucky, as a Black man, to have a job as a porter on a train that crisscrosses the continent. He has to smile and nod for the white passengers when they call him ‘George.’ He’s obsessed with teeth, and saving up tips for dentistry school.

On this trip, the passengers are unruly, especially when the train is stranded for days – their secrets leak out, blurring with Baxter’s sleep-deprivation hallucinations. When he finds an illicit postcard of two men, Baxter’s longings are reawakened; keeping it puts his job in peril, but he can’t part with it or his memories of a certain Porter Instructor.

The Words that Remain by Stênio Gardel (Brazil) tr. Bruna Dantas Lobata (Portuguese) – A letter has beckoned to Raimundo since he received it over 50 years ago from his youthful passion, handsome Cícero. But having grown up in an impoverished area of Brazil where demands of manual labor thwarted his becoming literate, Raimundo has been unable to read. Exploring Brazil’s little-known hinterland as well its urban haunts, this is a sweeping novel of repression, violence, and shame, along with survival, endurance, and the ultimate triumph of an unforgettable figure on society’s margins. The Words That Remain explores the universal power of the written word and language, and how they affect all our relationships.

The World and All That It Holds by Aleksandar Hemon (Bosnia/US) – “The World and All That It Holds would be an audacious title for a book by anybody except God–or Aleksandar Hemon. . . From start to finish, no matter what else he’s up to, Hemon is telling a tale about the resilience of true love.” —RON CHARLES, The Washington Post. The World and All That It Holds—in all its hilarious, heartbreaking, erotic, philosophical glory—showcases Aleksandar Hemon’s celebrated talent at its pinnacle. It is a grand, tender, sweeping story that spans decades and continents. It cements Hemon as one of the boldest voices in fiction.

This Other Eden by Paul Harding (US) – inspired by the true story of Malaga Island, an isolated island off the coast of Maine that became one of the first racially integrated towns in the Northeast. In 1792, formerly enslaved Benjamin Honey and his Irish wife, Patience, discover an island where they can make a life together. Over a century later, the Honeys’ descendants and a diverse group of neighbors are desperately poor but nevertheless protected from the hostility on the mainland. During the summer of 1912, Matthew Diamond, a retired, idealistic but prejudiced schoolteacher-turned-missionary, disrupts the community’s fragile balance. (Bibliotheca Alexandrina) This Other Eden is an exceptional novel. It is lyrically expressed historical fiction which is “a tribute to community and human dignity.” (Rachel Seiffert, The Guardian)

Thistlefoot by Genna Rose Nethercott (US) – The Yaga siblings have been estranged since childhood. Then they learn that they are to receive an inheritance: a sentient house on chicken legs. Thistlefoot, as the house is called, has arrived from the Yagas’ ancestral home outside Kyiv—but the sinister Longshadow Man has tracked it to American shores, bearing with him violent secrets from the past. As the Yagas embark with Thistlefoot on a final cross-country tour of their family’s traveling theater show, the Longshadow Man follows, seeding destruction in his wake. Ultimately, time, magic, and legacy must collide—erupting in a powerful conflagration to determine who gets to remember the past and craft a new future.

Ti Amo by Hanne Ørstavik (Norway) tr. Martin Aitken – A woman is in a deep and real, but relatively new relationship with a man from Milan. She has moved there, they have married, and they are close in every way. Then he is diagnosed with cancer. It’s serious, but they try to go about their lives as best they can. But when the doctor tells the woman that her husband has less than a year to live – without telling the husband – death comes between them. She knows it’s coming, but he doesn’t – and he doesn’t seem to want to know. An incredibly beautiful and harrowing novel, filled with tenderness and grief, love and loneliness.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin (US) – This is the story of Sam and Sadie. It’s not a romance, but it is about love. When Sam catches sight of Sadie at a crowded train station one morning he is catapulted straight back to childhood, and the hours they spent immersed in video games. Their spark reignited, together they get to work: making their own games to delight and challenge players. It’s the 90s, and anything is possible. Their collaborations make them superstars.What comes next is a tale of friendship and rivalry, fame and creativity, betrayal and tragedy, perfect worlds and imperfect ones. And, above all, of our need to connect: to be loved and to love.

When We Were Fireflies by Abubakar Adam Ibrahim (Nigeria) – When brooding artist, Yarima Lalo, encounters a moving train for the first time, two serendipitous events occur. First, it triggers memories of past lives in which he was twice murdered—once on a train. He also meets Aziza, a woman with a complicated past of her own, who becomes key to helping him understand what he is experiencing. With a third death in his current life imminent, together they go hunting for remnants of his past lives. Will they find evidence that he is losing his mind or the people who once loved or loathed him?