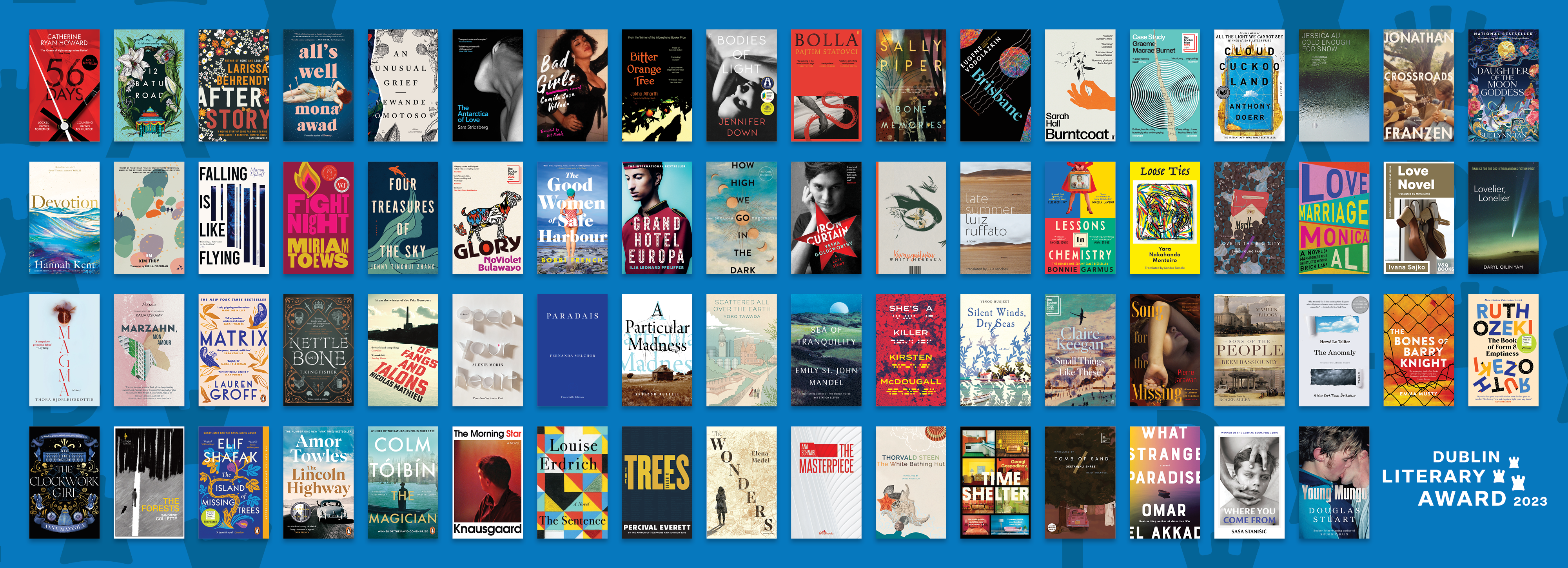

With books nominated by 84 international libraries from 31 countries across Africa, Europe, Asia, the US, Canada, South America, Australia, and New Zealand, the full longlist of 70 novels has been announced for the Dublin Literary Award 2023. The €100,000 award is presented annually for a novel written in English or translated into English.

The nominations include 29 novels in translation and 14 debut novels. Among the translated books are novels originally published in Arabic, Bulgarian, Dutch, Hindi, Korean, Slovene, Icelandic, Japanese, Norwegian, Spanish, French, Dutch, Portuguese and more.

The international panel of judges who will select the shortlist and winner, features Gabriel Gbadamosi, an Irish and Nigerian poet, playwright and critic based in London; Marie Hermet, a writer and translator who teaches creative writing and translation at the Université Paris Cité; English writer Sarah Moss who is the author of eight novels and teaches creative writing at UCD; Doireann Ní Ghríofa who is a bilingual poet, essayist, translator and author of A Ghost in the Throat; and Arunava Sinha who translates fiction, non-fiction and poetry from Bengali to English and has won several translation awards in India.

The shortlist will be revealed on 28th March and the winner on 25th May 2023.

I have read two of the novels, the wonderful East German Marzhan, mon Amour which I adored, an uplifting semi-autobiographical novella that is a celebration of community, and the Irish novella Small Things Like These, I’m one of the few who didn’t get on with this novel, despite its popularity.

It’s a wide-ranging selection and it will be interesting to see what makes the shortlist. There are a few familiar authors I’m interested in who I’ve read before like Elif Shakaf, Louise Erdrich, Kim Thúy and Yewande Omotoso and those I’m aware of, that I’d like to try like the award winning Canadian author Omar El-Akkad.

Let me know what you’ve enjoyed or are tempted by in the comments below:

The Longlist

Below are all the titles on the longlist, with their genre and the country of origin of the author plus the comments made by the nominating library(s).

56 Days (Crime/Thriller Fiction) by Catherine Ryan Howard (Ireland)

“a gripping and unputdownable thriller. Its structure is interesting going between the present, when a body has been found, and the 56 days preceding this gruesome discovery. Though fictional it deals realistically with the horrors of the real-life pandemic situation that the world had experienced during the previous two years.” – Cork City Libraries

912 Batu Road (Historical/Migration Fiction) by Viji Krishnamoorthy (India of Tamil/Hokkein-Chinese)

Viji Krishnamoorthy’s sweeping debut novel deftly weaves together vibrant fiction and meticulous research on the heroic exploits of Malayan wartime heroes – Sybil Kathigasu, Gurchan Singh and many others – who fearlessly fought for their beloved country.

Viji Krishnamoorthy’s sweeping debut novel deftly weaves together vibrant fiction and meticulous research on the heroic exploits of Malayan wartime heroes – Sybil Kathigasu, Gurchan Singh and many others – who fearlessly fought for their beloved country.

“This novel was chosen for its interesting history and patriotisms of Malaysia and Malaysians. It displays how Malaysia is a harmonious country that embraces multiracial aspects.” – National Library of Malaysia

A Particular Madness (Fiction) by Sheldon Russell (USA)

“In his novel, Russell explores mental illness through the experience of the main character: Jacob Roland. Set in Oklahoma, the novel showcases the reality of rural America at a time when mental illness was often misunderstood and mistreated, as it still is today.” – Oklahoma Department of Libraries, USA

After Story (Fiction) by Larissa Behrendt (Australia)

“It’s a beautifully written story, fascinatingly revealed via alternating perspectives from a mother and daughter using overseas literary travel to try to mend a difficult relationship, and illuminating the complex nature of familial ties, buried grief and historical trauma.” – Libraries Tasmania, Australia

All’s Well (Fiction/Horror) by Mona Awad (Canada)

A piercingly funny indictment of our collective refusal to witness and believe female pain.

“The plotting is a clever mishmash of Shakespeare, obviously MacBeth and All’s Well That Ends Well, though there’s a little Tempest thrown in as well. But Awad doesn’t make herself a slave to what Shakespeare dictates. She has entwined the Scottish play so brilliantly in a brutal theatre production of All’s Well, that the power plays, the ghosts, the betrayals, the madness, are seamlessly incorporated. How Awad came up with all this is fascinating.” – Cleveland Public Library, USA

An Unusual Grief (Fiction) Yewande Omotoso (Barbados/Nigeria/South Africa)

“We were absolutely blown away by An Unusual Grief. Felt an instant connection to the book, perhaps because it has a local setting or the daily issues of life that it confronts. While it deals with grief, it is not a gloomy book, thanks in large part to the art of storytelling that Omotoso displays throughout the novel. It is a beautifully written book that is raw in its emotion as it covers and conveys the many layers of grief.” – City of Capetown Library and information Services

Bad Girls (Fiction) by Camila Sosa Villada (Argentina) tr. Kit Maude (Spanish)

“We really loved this novel. The heroines are transgender women whose lives are absolutely complicated… They are rejected by the whole society and especially by those who use to deal with them as prostitutes.

The novel shows a solidarity and a humanity that delighted us. And even though the story is rather tragic there is a craziness and a hymn to life and joy that makes this book unforgettable.” – Bibliothèques municipales de Genève, Switzerland

Bitter Orange Tree (Literary Fiction) Jokha Alharthi (Oman) tr. Marilyn Booth (Arabic)

“Narrated in first person, the story unfolds vividly in prose full of pictures, stories, names and objects of a childhood and youth in the Middle East and the richness of Arabian culture. All these narrative elements mingle with dreams of the young woman and regrets of missed chances to close up on her own self. Bitter Orange Tree is the coming-of-age of a young woman that still has yet to fully explore her own identity.” – Stadtbücherei Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Bodies of Light (Literary Fiction) by Jennifer Down (Australia)

“Bodies of Light has been nominated by popular vote from public library staff across Victoria.” – State Library of Victoria, Australia

“Bodies of Light has been nominated by popular vote from public library staff across Victoria.” – State Library of Victoria, Australia

Bolla (Fiction) by Pajtim Statovci (Albania/Finland) tr. David Hackston (Finnish)

“Albanian protagonist, Arsim, is a brilliant student and just married to his young wife. He’s also in love with a person who is wrong for him in two ways: Miloš is a man and a Serb. Violence takes Arsim over and he get punished both physically, mentally and socially. Bolla is a phenomenal literal study of love, loneliness, passion and violence. It pictures the horrors of war and living a secret life.” – Helsinki City Library, Finland

Bone Memories (Fiction) by Sally Piper (Australia)

“Bone Memories is a brilliant and devastating novel about a mother’s grief for her lost daughter, Jess, and a son’s grief about losing his mother. It begins sixteen years after Jess’s murder, with the victim’s family continuing to grapple with the lives they face ahead and their memories of her. The novel is set in Queensland and is written by Brisbane-based author Sally Piper.” – State Library of Queensland Australia

Brisbane (Historical Fiction) by Eugene Vodolazkin (Ukraine) tr. Marian Schwartz

Brisbane is a new novel by the the international bestselling author Eugene Vodolazkin – the winner of the Big Book Award, the Leo Tolstoy Yasnaya Polyana Award, and the Read Russia Award, the finalist of the Russian Booker Award. Vodolazkin also won the Solzhenitsyn Prize in 2019. He is a modern Thinker and Peacemaker who continues to develop traditions and heritage of a grand philosophical novel. – All Russia State Library for Foreign Literature

Burntcoat (Science Fiction/Dystopia) by Sarah Hall (UK)

“A love story taking place during a deadly pandemic, a story about dealing with an unknown virus and loss while at the same time creating a life during dire circumstances and creating art – subtle and heartbreaking.” – Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Switzerland

Case Study (Literary Fiction) by Graeme Macrae Burnett (UK)

“Macrae Burnett has created a dynamic work that has excellent characterisation with acute observation. The writing is layered but there is no use of superfluous words. While the themes are profound, the style is both intriguing and playful . He has created a book that is thought provoking and a compulsive read.” – Limerick City and County Libraries, Ireland

Cloud Cuckoo Land (Science Fiction/Fantasy) by Anthony Doerr (US)

“This book had good storytelling in spades. Each of the characters has a relationship with a librarian, Zeno and Seymour with the librarians in Lakeport, Idaho, Anna with scribes in Constantinople, Omeir with Anna, and Konstance with the AI controller of her ship. This beautifully written book is a shining example of hope.” – Bács-Kiskun Megyei Katona József Könyvtár, Hungary

Cold Enough For Snow (Literary Fiction) by Jessica Au (Australia)

“Cold Enough for Snow is something like an ephemeral waterfall. The story, of a woman and her mother travelling in Japan, unfolds with grace – not a thundering cascade but a slow trickling that still has the power to, in time, soften the rock below into shape. The prose is elegant and unpretentious, making inferences but not enforcing meaning. The story speaks to the complexity of our relationships with those we love, and also nods towards some of the richness and value of travel and being present outside of our regular environments.The novel pushes and pokes at notions of identity, belonging and perception; invoking colour and description to honour the importance of observation, care and attention. It is a work of great softness and strength.” – The National Library of Australia

Crossroads (Domestic Fiction) by Jonathan Franzen (US)

“Suspense” – Öffentliche Bücherei -Anna Seghers, Germany

Daughter of the Moon Goddess (Fantasy Fiction) by Sue Lynn Tan (Malaysia/Hong Kong)

“Daughter of the Moon Goddess is jam-packed novel that follows Xingyin on her path to self-discovery as she tries to free her mother and herself from their eternal confinement on the moon.

“Daughter of the Moon Goddess is jam-packed novel that follows Xingyin on her path to self-discovery as she tries to free her mother and herself from their eternal confinement on the moon.

Inspired by Chinese Mythology’s Chang’e, each word of this novel is thoughtfully chosen and crafted poetically, taking you on an almost dreamy adventure from start to finish. There is amazing world building done by Tan and a wonderful female protagonist that is strong and determined. This novel is filled with magic, powerful creatures, secrets, betrayals, amazingly written battle scenes, and even a love triangle – though that doesn’t shadow over anything. Wonderful, adventurous book.” – Kansas City Public Library, USA

Devotion (Historical Fiction) by Hannah Kent (Australia)

“The story and the characters of the book are so perfect. We love Hannah’s Kent writing and the way that it just connects with our thoughts, mind, and soul.” – Veria Central Public Library, Greece

Em (Historical/Literary Fiction) by Kim Thúy (Vietnam/Canada) tr. Sheila Fischman (French)

“Kim Thúy seals words into packets, plain and firm as an encyclopedia entry; shimmery and taut as an ode; pitted and unbendable as a curse, lays them edge to corner to end to say, do you see it now? Do you?” – Hartford Public Library, USA

Falling is like Flying (Fiction) by Manon Uphoff (Netherlands) tr. Sam Garrett (Dutch)

“Falling is Like Flying is an impressive novel in which author Manon Uphoff demonstrates what literature is capable of. With all her literary power, Uphoff manages to reveal a history that seems almost impossible to tell. A history of sexual abuse by a dominating father called the Minotaur is uncovered in a devastating personal mythology. In this novel, the Minotaur is finally overcome in his labyrinth by the power of language.” – KB, National Library of the Netherlands

Fight Night (Fiction) by Miriam Toews (Canada)

“Told in the unforgettable voice of nine-year old Swiv, this is a story of life, death, birth and intergenerational trauma that is both hilarious and heart-breaking. Swiv, the youngest of three fierce women, is worrying about her aging grandmother’s health and her pregnant mother’s mental health. All while her feisty (and deeply mortifying) grandmother tries to impart life lessons about fighting – both to survive and to find joy.” – Toronto Public Library, Canada

Four Treasures of the Sky (Historical Fiction) by Jenny Tinghui Zhang (China/US)

“This debut novel is a stunner, historical fiction at its best (captivating, illuminating and provoking) in its depiction and portrayal of the horrors of racism, discrimination, abuse and greed.

“This debut novel is a stunner, historical fiction at its best (captivating, illuminating and provoking) in its depiction and portrayal of the horrors of racism, discrimination, abuse and greed.

The author has threaded a deep understanding of Chinese calligraphic arts, that goes beyond artistic standards; referenced an eponymous heroine in a classic Chinese novel; included historical events about Chinese Americans that have been relegated and left to fade away; revealed the graphic horror of a childhood cut short; and created a protagonist who continuously reinvents herself, in order to survive, and also to discover who she really is. It is no small achievement that Jenny Zhang has written a book of arresting beauty about horrific events.” – Los Angeles Public Library, USA

Glory (Literary Fiction) by NoViolet Bulawayo (Zimbabwe)

“Bulawayo’s reimagining of the overthrow of Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s infamous authoritarian ruler, features a cast made up entirely of talking animals (Mugabe is the Old Horse). Bulawayo’s gift for storytelling is dazzling.” –Boston Public Library, USA

“The use of language in the novel colourful, poetic and also comedic illustrates the absurdity and surreal nature of a police state , built with the structure of animal stories that are typical of African tradition.”–Biblioteca Vila de Gràcia, Barcelona, Spain

Grand Hotel Europa (Fiction) by Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer (Netherlands) tr. Michele Hutchison (Dutch)

“It is a monumental novel about loss, the immigration crisis, the history and future of Europe, Mass tourism and many more themes. A phenomenal read which lets you think about modern day Europe.” – De Bibliotheek Utrecht, The Netherlands

How High We Go in the Dark (Science Fiction/Short Stories) by Sequoia Nagamatsu (Japan/US)

“This novel in interlinked stories presents a complex and deeply humane look at grief and survival in a post-apocalyptic world. “– Multnomah County Library, USA

Iron Curtain: A Love Story (Historical/Literary Fiction) by Vesna Goldsworthy (Serbia/UK)

“Iron Curtain uses a bitter-sweet story of a doomed love affair between Milena, a communist Red Princess, and Jason, a self-declared Irish Marxist poet, to probe the political divisions of Europe which continue to affect us all. It echoes the myth of Medea in its gripping tale of Western betrayal and Eastern revenge.

It is a spellbinding novel: vividly original, tense and often hilarious in its extraordinary evocation of two wildly contrasted worlds. It brings to mind the best political fiction from Eastern Europe, such as the works of Pasternak and Kundera, now in an inimitable British-Serbian woman’s voice. With the passing of the period of optimism which followed the fall of the Berlin Wall the fractured world described in this novel has an ominous resonance today.” – Belgrade City Library, Serbia

Kurangaituku (Literary Fiction/Mythology) by Whiti Hereaka (New Zealand)

“Kurangaituku takes readers on an immersive journey through deep time with its shape-shifting lead character. An exploration and reclamation of indigenous storytelling, it shows how language can create, shape, give life and destroy, with “one hundred lifetimes or more able to be lived by a single being.

“Kurangaituku takes readers on an immersive journey through deep time with its shape-shifting lead character. An exploration and reclamation of indigenous storytelling, it shows how language can create, shape, give life and destroy, with “one hundred lifetimes or more able to be lived by a single being.

The world of Kurangaituku is visceral and sensual, and Hereaka’s flowing and hypnotic prose is made for reading aloud. Its looping narrative structure is seamlessly woven together with the book’s double-sided and interlocking format, reflecting the Māori worldview of the circularity of life and death, transfiguration and rebirth and allowing the story to be formed and reformed in the space between author and audience. A multi-dimensional and unforgettable book.” – Auckland Council Libraries

“Kurangaituku is the retelling of a legend and so much more. It is about the power of our voices to tell our own story. It is about the importance of story to ourselves and to our culture, and the destructive nature of someone else telling or supplanting our story as part of colonisation. An amazing, thought-provoking, beautifully lyrical work. ‘Do you see what their stories have done?…They have made monsters of us both’.” – Christchurch City Libraries

Late Summer (Literary Fiction) by Luiz Ruffato (Brazil) tr. Julia Sanches (Portuguese)

“Late Summer is an excellent reflection on the effects of isolation. A book that shows both a portrait of contemporary society, in which social classes have ruptured any form of a dialogue between them, and a realistic story of a man tortured by his unsuccessful attempt to redeem his past.

The main character, Oséias, abandoned by his wife and son, decides to go back to his hometown after twenty years away. On a six-day journey trying to reconnect to his family, as a flaneur, he retraces his boyhood and shares by streams of consciousness old memories and thoughts mingled with a detailed narrative of the events of the journey. The novel also unveils the feeling of inadequacy present in our time and presents a philosophical and perennial question of belonging.” – Sistema Nacional de Bibliotecas Públicas/Biblioteca Demonstrativa do Brasil

Lessons in Chemistry (Popular Fiction) by Bonnie Garmus (US)

“Author Bonnie Garmus provides an original storyline that is refreshing, humorous, and very timely.” -Miami-Dade Public Library

” This is a brilliant story – of a woman who is determined to make her mark on the world and not willing to let anyone get in her way. She’s feisty, heroic, and intelligent, and she unwittingly becomes the star of a TV cookery show, aimed at teaching the nation how to make food that matters. The show becomes a call to arms to the millions of women who follow her ‘lessons in chemistry’ encouraging all to ‘use the laws of chemistry and change the status quo.’” -Norfolk Library, UK

“Great story of women empowerment set in the 1960’s.” – Laramie County Library System, US

Loose Ties (Fiction) by Yara Nakahanda Monteiro (Portugal) tr. Sandra Tamele

“This book is both a story of love and of war, a contemporary tale that deals with the past, a call for the independence of women as political beings. And of their own bodies in search of freedom.

Yara Monteiro revisits a personal and collective history, in which the lives of expatriates who suffer the discomfort of a painful isolation are retraced. This novel is a deep, funny, and courageous novel that gives Angolan women a voice, while reflecting on identity issues.” – Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto, Portugal

Love in the Big City (Literary Fiction) by Sang Young Park Korea) tr. Anton Hur

“The novel follows the life of a young gay man in Seoul. It delves into identity, growth, pain through a queer lens. The story is set in Seoul but has a western sensibility. It is relatable and universal for readers of all background. The narrative is simple but intense and sensory with both humour and emotion. And there is in the end surprising poignancy and depth. Award-winning for its unique literary voice and perspective. The translation is great.” – Bucheon City Library, Republic of Korea

Love Marriage by Monica Ali (Bangladesh/UK)

“A clash of cultures evolves into a delicate examination of the ways in which both immigrant and non-immigrant families have shaped their children, diffusing unexplored suffering across generations.” – Milwaukee Public Library, USA

Love Novel by Ivana Sajko (Croatia) tr. Mima Simić

“Love Novel tells the story of a young married couple whose relationship is affected by the struggles of everyday reality. They are fighting for the survival of their love and the meaning of life in conditions of extreme economic insecurity. The lack of communication affects the relationship resulting in slow deterioration, followed by general dissatisfaction. This “love novel” becomes relevant again in today’s situation of new economic crises that we all face.” – Rijeka City Library, Croatia

Lovelier, Lonelier (Fiction) by Daryl Qilin Yam (Singapore)

“Lovelier, Lonelier is a strong study of character and explores the emotional impact of love and loss in a narrative that spans multiple countries. The writing is self-assured in its ability to connect the various characters through a number of personal tragedies. The novel tackles meaningful themes such as the nature of reality, the role of chance, intergenerational trauma, and the power of art to redeem or destroy.” – National Library Board of Singapore

Magma (Literary Fiction) by Thóra Hjörleifsdóttir (Iceland) tr. Meg Matich

“Magma is the first novel by Thóra Hjörleifsdóttir. In the book, she talks about the dark side of love and invisible violence. The main character Lilja falls in love with a man and is ready to go to great lengths for him. When she stops setting limits for him, Lilja loses control of herself and reality. A very interesting and well written book about a difficult subject that paints a picture of an abusive relationship.” – Reykjavík City Library, Iceland

Marzahn, Mon Amour (Uplifting Fiction) by Katja Oskamp (Germany) tr. Jo Heinrich – read my review here

“It is a book that allows a deep insight into the daily lives of the so called ordinary people. The author treats each of them with respect and approaches with careful empathy.” – Stadtbüchereien Düsseldorf, Germany

“It is a book that allows a deep insight into the daily lives of the so called ordinary people. The author treats each of them with respect and approaches with careful empathy.” – Stadtbüchereien Düsseldorf, Germany

Matrix (Fiction) by Lauren Groff (US)

“Matrix stands out for its exquisite use of language, particularly Groff’s seamless weaving of psalms and liturgical texts into the narrative, marrying the miraculous and the mundane into one ecstatic tapestry of feminine power.” – Richland Library, USA

Nettle and Bone (Fantasy/Horror Fiction) by T. Kingfisher

“The book mixes fantasy and feminist elements that are not exaggerated but instead very convincing because of Kingfisher’s thoughtful narrative style. This is adult fantasy literature far away from cliché featuring unique characters and surprising incidents.” – Universitätsbibliothek Bern, Switzerland

Of Fangs and Talons by Nicolas Mathieu (France) tr. Sam Taylor

“A bleak tale of the disenfranchised, in this case the factory workers and others living in a small town in the Vosges region of France. Things start to go downhill when the factory is set to close, then it gets worse. Compelling enough to want to read all in one sitting. Very excellent.” – The State Library of South Australia

Open Your Heart (Auto-fiction) by Alexie Morin (France) tr. Aimee Wall

“Open your Heart is an autobiographical novel depicting the story of two friends linked by a condition of illness and operation at a young age. A strong narrative that shed light through sufferings, power beyond discomfort, without restraint.” – Bibliothéque de Québec, Canada

Paradais (Literary Fiction) by Fernanda Melchor (Mexico) tr. Sophie Hughes (Spanish)

“The pace and intensity of the narration transmits all the sorrow, anger, and frustration that might make one empathize with some characters; and yet the novel is also relentless to show how coward self-justification and the inexcusable, selfish relief of one’s anger can make a victim as vile as any victimiser. The author thus depicts in few pages the complexity of human beings and of the context of their actions.” – Biblioteca Daniel Cosío Villegas, Mexico

Scattered All Over the Earth (Science Fiction/Dystopia) by Yoko Tawada (Japan) tr. Margaret Mitsutani

“In a not too distant future, Japan has disappeared from the face o the earth due to an environmental catastrophe. In Yoko Tawada’s latest novel, we follow Hiruko, a climate refugee on her trip through Europe searching for someone else who speaks her mother tongue. Others join her and the small group is traveling from one bizarre and thoroughly comical situation to the next. It is fascinating how Tawada manages to combine the themes of our time in this first part of a planned trilogy: climate change, migration, globalization – and above all the key question: What does language mean for identity and human community?” – Zentral und Landesbibliothek, Berlin, Germany

Sea of Tranquility (Speculative/ Science Fiction) by Emily St. John Mandel (Canada)

“A fantastic (in all senses of the word) novel that somehow weaves a mystery and time travel and colonies on the moon and a pandemic and a double homicide together into a beautiful, life-affirming story.” – Winnipeg Public Library, Canada

“A fantastic (in all senses of the word) novel that somehow weaves a mystery and time travel and colonies on the moon and a pandemic and a double homicide together into a beautiful, life-affirming story.” – Winnipeg Public Library, Canada

“A masterpiece of speculative fiction, tying together historical fiction, time travel and references to our own experiences living through the Covid-19 pandemic in an ultimately hopeful exploration of the nature of existence and human connection. A time traveling detective sent to gather evidence about a rift in the fabric of reality is the thread that draws together disparate characters across centuries including an author very similar to St John Mandel herself. She writes beautifully, rendering the old growth forests of British Colombia and decaying moon colonies of the future equally with equal parts romance, imagination and vivid detail, instilling nostalgia for both. Captivating, deceptively light, Sea of Tranquility nevertheless touches on weighty topics—colonialism, the environment, loneliness, morality in a thought-provoking way.” – Ottawa Public Library, Canada

She’s a killer (Fiction) by Kirsten McDougall (New Zealand)

“Set in the very near future in New Zealand where the effects of climate change are really beginning to bite and affect both our physical world but also our society. The book is multi-layered, often very funny in a dark way, contains many layers of twists and turns and is a fabulous read to boot. It’s a fast-paced thriller which boasts great and complex characters. It’s both personal and intimate and about New Zealand and also the World simultaneously, dealing with global issues and events in a unique fashion.” – Wellington City Library, New Zealand

Silent Winds, Dry Seas by Vinod Busjeet (Mauritius/US)

“We are happy to nominate this novel from a local writer. The writing is engaging and evocative. The poetry of language successfully evokes a richly tropical, multi-sensual ambience. The scents are olfactible, colours brilliant, heat diaphoretic. The author skillfully dramatizes and limns distinctive and fascinating characters: Vishnu’s extended and extensive family, and community members and neighbours, fully developing their individual personalities and visages. They are not cardboard, they breathe. The plot itself incorporates global historical events as well as those in the Mauritian march to independence that serve to place the story in time. The end result is that you enjoy a quick-paced story while learning a bit about a place you never have been. A thoroughly enjoyable read.” – DC Public Library, USA

Small Things Like These (Fiction) by Claire Keegan (Ireland) – Read my review here

“With exceptional grace, economy and storytelling skill, Keegan has penned a classic story of moral courage that encapsulates so much of what it means to be human today. This short novel is bigger than any award but deserves all the recognition it can get.”– Chicago Public Library

“A tiny, perfect novel reminding us of a shameful part of Ireland’s history, seen through the eyes of a coal merchant whose eyes are opened to the iron grip of the Catholic church on the hearts and minds of his community. Heart-breaking and thought provoking.” – Waterford City and Council Library Services

“116 pages of beautifully written prose, the story centres around Bill Furlong, his upbringing, and his empathy to the inmates of the local Magdalene convent. Claire Keegan’s sublime and moving novel, covering the weeks before Christmas 1985, shows the importance of facing up to our past, and the historic collusion between Church, State, and Irish society. As Bill’s wife remarked; “If you want to get on in life, there’s things you have to ignore, so you can keep on.” – Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown Libraries, Dublin

“The master storytelling is in Furlong, as the gentle quiet hero. The reader would follow him to the darkest pits and back, and we do. This is a really important novel for a society where absolute authority has reigned. By the end of this book, the soul feels a little healed. “– Galway Public Libraries

Song for the Missing (Historical Fiction) by Pierre Jarawan (Lebanon/Germany) tr. Elisabeth Lauffer (German)

“2011. During the troubled times of the Arabic Spring, Amin recalls the year 1994, when he, as an orphan, came with his Grandma from Germany to Lebanon. He remembers the taboo of speaking about the 17.000 missing people in Lebanon and the silent grief of their relatives. Little by little, Amin discovers that his parents belong to the missing persons. With his friend Jafar, Amin roams Beirut and its traumatized population, until he meet a story teller, who sparks Amin’s interest in books.

Rooted in the oral storytelling traditions of the Orient and passionate, Pierre Jarawan narrates stories of the people of Lebanon to make the reader feel what is lost. A touching, political novel and a varied family story. “– Leipziger Städtische Bibliotheken, Germany

Sons of the People: The Mamluk Trilogy (Historical Fiction) by Reem Bassiouney (Egypt) tr. Roger Allen (Arabic)

“Set against a historical backdrop, Sons of the People: The Mamluk Trilogy sheds light on the last days of the Mamluk dynasty before its downfall. The Mamluks were defeated by the Ottoman troops in 1517 at the battle of Marj Dabiq, after which Tuman Bay was beheaded. The incidents of the trilogy start with the story behind the construction of the mosque of Sultan Hassan, whose architect is the offspring of a Mamluk prince who married an Egyptian girl, Zineb, under duress. Eventually, the mosque appears to be the dominant motif in the trilogy, which creates a well-wrought narrative, helping Bassiouney to depict a vivid picture of the social, political and economic life in Egypt under the rule of the Mamluks; a period that has always raised very controversial questions concerning its cultural and political inheritance. With the second story, the narrative shifts to different times where the very mosque becomes a bloodbath of the fighting Mamluks. In the final one, the conquering army ravishes the riches of mosque. Reem Bassiouney is a distinguished Egyptian novelist. She also received the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature.” – Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Egypt

The Anomaly (Popular Fiction) by Hervé Le Tellier (France) tr. Adriana Hunter

“In this highly original and inventive novel, Hervé le Tellier introduces his characters in chapters very different in tone to mix such genres as thriller, science-fiction, comedy or spy novel. Though mostly entertaining in tone with its use of pastiche and satire, the novel also tackles darker issues such as homophobia in the world of hip hop, cancer, child abuse, intricate love affairs, unethical business. This puzzling speculative fiction with its spatio-temporal rift also questions our perception of reality and ourselves.” – Bibliothèque publique d’Information, Paris, France

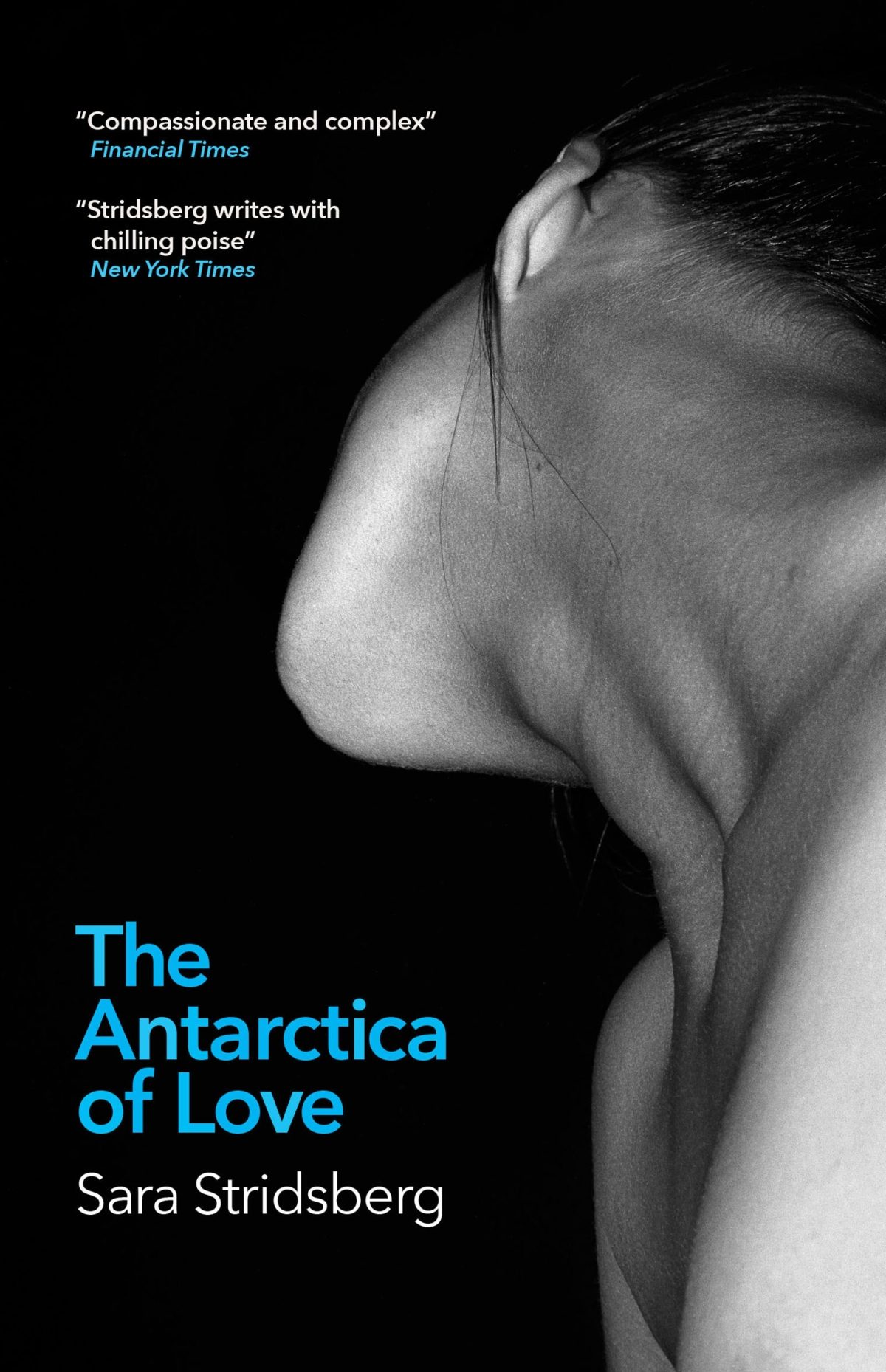

The Antarctica of Love(Literary Fiction) by Sara Stridsberg (Sweden) tr. Deborah Bragan-Turner

“Inni, a prostitute and drug addict, is brutally murdered in a forest. From the realm of the dead, she recounts her broken life. Rhythmically, her story returns to the end point of her existence, when the Hunter has ushered her into his car for a final journey. Carried by a powerful and poetic writing, this book sublimates the unbearable.” – Bibliothèque Municipale de Reims, France

“Inni, a prostitute and drug addict, is brutally murdered in a forest. From the realm of the dead, she recounts her broken life. Rhythmically, her story returns to the end point of her existence, when the Hunter has ushered her into his car for a final journey. Carried by a powerful and poetic writing, this book sublimates the unbearable.” – Bibliothèque Municipale de Reims, France

The Bones of Barry Knight (Social Justice Fiction) by Emma Musty (UK)

“The Bones of Barry Knight is a contemporary novel focusing on a refugee camp in an unnamed country. It is very moving as it depicts the impact of war on everyday people. It is raw and unflinching, but also full of poignant beauty.” – Redbridge Library London, UK

The Book of Form and Emptiness (Literary Fiction/Magic Realism) by Ruth Ozeki (US)

“This beautifully written book deals with issues of family love, mental illness, grief and loss, and the importance of friends. It is philosophical, heart-breaking and empowering, and it is also full of joy.” -Dunedin Public Libraries, NZ

“The newest title from a beloved local author, this book takes place between the public library and the youth psych ward. It is simultaneously whimsical, philosophical, and heart-wrenching. It blends sympathetic characters and a vigorous engagement with everything from our attachment to material possessions to the climate crisis.” -Vancouver Public Library, Canada

The Clockwork Girl (Historical/Gothic Fiction) by Anna Mazzola (UK)

“A thoroughly immersive read, captivating and utterly thrilling. It’s easy for the reader to ensconce oneself in its masterfully crafted, self-contained universe. The historical setting is commendably subtle, suggested rather than imposed upon the reader. Simply superb!” – Tampere City Library, Finland

The Forests (Fiction/Dystopia) by Sandrine Collette (France) tr. Alison Anderson (French)

“The world is on fire. Only armed with love and hope, the young Corentin begins a terrible journey to the remote Valley of Forests, looking for Augustine his adoptive grandmother. A powerful and frightening post-apocalyptic novel.” – Réseau de Bibliothéques de Colmar, France

The Good Women of Safe Harbour (Uplifting Fiction) by Bobbi French (Canada)

“The Good Women of Safe Harbour by Bobbi French is a brilliant novel with rich characters and a strong sense of place. Set in Newfoundland in the final, beautiful summer of Frances Delaney’s “small” life, this book is wildly joyful and deeply sad. It challenges the reader to reevaluate the ways in which we see our lives, the good and the bad. This novel handles such difficult topics as mental illness, assisted suicide, abortion and mothers separated from their children while never for a moment leaving the central premise that life is beautiful and precious and must be celebrated. This book is a celebration.” – Newfoundland and Labrador Public Libraries, Canada

The Island of Missing Trees (Fiction) by Elif Shafak (Turkey/UK)

“This was a beautifully written book that wove true historical events into a thought provoking and emotional book. The characters are fully formed and bring to life the story of turmoil, betrayal, the need for understanding and acceptance , flitting between the present day and 1970s. The Fig Tree was a particularly unique narrator – and a reminder of the impacts of war of community and nature.” – Glasgow Life, Scotland

“This was a beautifully written book that wove true historical events into a thought provoking and emotional book. The characters are fully formed and bring to life the story of turmoil, betrayal, the need for understanding and acceptance , flitting between the present day and 1970s. The Fig Tree was a particularly unique narrator – and a reminder of the impacts of war of community and nature.” – Glasgow Life, Scotland

“A love story and a history of a long-lived conflict in the Island of Ciprus, love and hate, memory and trauma are perfectly represented.” -Biblioteca Nazionale Vittorio Emanuele III – Napoli

“The Island of Missing Trees is a cleverly constructed novel with a touch of magical realism. It is masterfully told and written in an elegant language. Shafak explores the consequences of the civil war on ordinary lives and future generations. Highlighted themes are migration, homophobia, religion, loss and family secrets. Shafak inspires and delivers a beautiful, powerful novel full of empathy and hope.” – Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge (Bruges Public Library)

“This novel provides a human and compassionate account of tragic, traumatising, troubling and turbulent past of Cyprus. It shows us fractured communities torn apart by war, partition, division, religion, love, loss, grief, migration, the natural world, and the search for a sense of identity and belonging that refuses to be denied. Shafak writes through the prism of hope, moving on, renewal and healing, of the need to tell the stories of the past, rather than burying them, addressing the issues that hurt, and extend our concern and eyes to the natural world, to recognise its central integral place, like the fig tree growing in the tavern, within humanity and connect with it in the way our ancestors would have done.” – Rede de Bibliotecas de Lisboa

The Lincoln Highway (Popular Fiction) by Amor Towles (US)

“This title was the most popular 2021-22 Adult Fiction book read by Iowa City Public Library patrons last year.” – Iowa City Public Library

The Magician (Literary Fiction) by Colm Tóibín (Ireland)

“A beautifully written fictionalised biographical novel about Thomas Mann. He struggles to come to terms with disaster in his family, hidden desire and nationality. He opposes Nazism and has to flee from Germany to the United Stated and Switzerland. The novel triggers you to (re)read the work of Nobel Prize winner Thomas Mann.” – Openbare Bibliotheek, Gent, Belgium

The Masterpiece by Ana Schnabl (Slovenia) tr. David Limon

“What really interests the author and what she excels at showing is the human condition, the motivations and desires of her characters. In rich literary prose, she discusses the cost of personal autonomy and the explosive power of love. She also provides insight into the writing process and sheds light on a vital component of producing art with the aid of her protagonists.” – Ljubljana City Library, Slovenia

“With The Masterpiece, Ana Schnabl proved her stylistic exceptionality, you don’t skip lines with her.” – Mariborska Libraries, Slovenia

The Morning Star by Karl Ove Knausgaard (Norway) tr. Martin Aitken

“The Morning Star is a staggering, ambitious work about the small and the grand things. We meet a collection of people, loosely connected, who each get to tell their story. One night, in the middle of regular life, an enormous star appears in the sky. Nobody knows what it is, and after a little while things go back to normal. But not quite.” – Solvberget Library and Culture Centre, Norway

The Sentence; A Novel (Fiction) by Louise Erdrich (US)

“The Sentence is a captivating and inventively crafted novel. Tookie, the main character, is a middle-aged Native American woman just getting by and working in a Minneapolis bookstore that specialized in subjects of Indigenous culture and history. We get to know Tookie and her friends and family very well. They are each unique yet very believable. Even the eccentric ghost who appears intermittently is believable. This novel has it all: a compelling plot, sometimes heart-breaking, sometimes laugh-out-loud funny; inventive word play; and a lively cast of colourful characters trying their best to honour their indigenous identities amid often cruel and inhospitable surroundings. – New Hampshire State Library, USA

The Trees: A Novel (Popular Fiction) by Percival Everett (US)

“The Trees is a powerful social satire of lasting importance.” – Free Library of Philadelphia, USA

The White Bathing Hut (Fiction) by Thorvald Steen (Norway) tr. James Anderson

“Since he was a youth he has lived with a rare muscle disease, but only when he is in his 60s and sitting in a wheelchair does he learn the truth about his grandfather and uncle, who had the same hereditary disease, and that his own mother never has told the truth.” – Olso Public Library, Norway

The Wonders (Literary Fiction) by Elena Medel (Spain) tr. Lizzie Davis and Thomas Bunstead

“Elena Medel’s first novel is a poetic and vivid portrait about two Spanish working-class women, Alicia y María, who are limited by class and gender dynamics. The novel stands out for its rhythmic prose and unforgettable characters.” – Biblioteca de Andalucía, Spain

Time Shelter by Georgi Gospodinov (Bulgaria) tr. Angela Rodel

“A dystopian vision of Europe and the world in the face of a personal and collective memory breakdown leading to ‘a flood of the past’. Smuggling poetry into fiction, his style is both poetic and philosophical yet readable, funny, self-ironic. Gospodinov’s literature is coming from a small language and territory in the periphery of Europe, but has the power of giving meaning and empathy through great narrative voices and storytelling skills.

He is the most read author not only at the Sofia City Library, but also at the libraries across the country. A number of meetings about the novel were held in the library with various readers, provoking interesting discussions. ” – Sofia City Library, Bulgaria

Tomb of Sand (Literary Fiction) by Geetanjali Shree (India) tr. Daisy Rockwell (Hindi)

“This is an amazing and experimentally written book. Geetanjali Shree’s playful tone and exuberant wordplay results in a book that is engaging, funny, and utterly original, at the same time as being an urgent and timely protest against the destructive impact of borders and boundaries, whether between religions, countries, or genders, highly recommend it, especially since it gives an insight to many customs and habits of India. A rare gem of a novel.” – India International Centre, India

What Strange Paradise by Omar El-Akkad (Canada)

“The refugee crisis told through the eyes of a child highlights the difficult circumstances of a group of Syrians on a boat in the Mediterranean, but underscores a sense of humanism binding all people together. ” – San Diego Public Library, USA

“The refugee crisis told through the eyes of a child highlights the difficult circumstances of a group of Syrians on a boat in the Mediterranean, but underscores a sense of humanism binding all people together. ” – San Diego Public Library, USA

Where You Come From by Saša Stanišić (Bosnia-Herzegovina/Germany) tr. Saša Stanišić (German)

“Saša Stanišić and his mixed family (Serbian and Bosnian) flee from Yugoslavia in the early 1990s and end up in Heidelberg, Germany, where they struggle to integrate, to a large extent because of the low paying jobs available to immigrants. Saša Stanišić tells his personal story in a touching, exciting and stylistic outstanding narrative Style. The novel was successful adapted for the Theater and won the German Book Prize in 2019.” – Stadtbücherei Heidelberg, Germany

“Third novel from internationally acclaimed and bestselling Bosnian-German author Saša Stanišic. The story follows a young refugee and his family who fled to Germany from Yugoslavia in the 1990s. A heartwarming and moving reflection on the process reshaping ones identity between countries, cultures and languages.” – Stadtbibliothek Bremen, Germany

Young Mungo (Fiction) by Douglas Stuart (Scotland/US)

“This is Stuart’s follow up to his debut Booker Prize-winning novel, Shuggie Bain, and while both books define themselves by a fractured Glaswegian family with an unreliable and fragile mother, Young Mungo turns toward the fifteen-year-old title character (named after the patron saint of Glasgow) as he navigates both first love and unrelenting danger.

This is a challenging novel of cruelty and carelessness where conflict – ideological and physical – persists, but Stuart’s compassionate mastery of language and storytelling provides an unexpected and gleaming tenderness.” – Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, USA

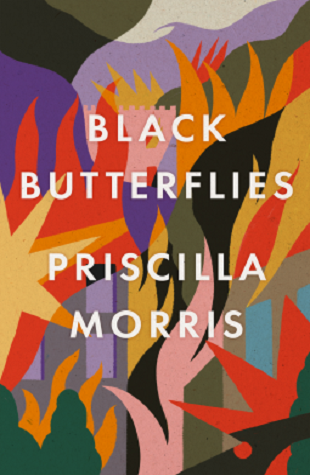

Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris (Yugoslav/Cornish – UK) (Historical Fiction)

Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris (Yugoslav/Cornish – UK) (Historical Fiction) Pod by Laline Paull (UK) (Nature/Oceanic Fantasy)

Pod by Laline Paull (UK) (Nature/Oceanic Fantasy) Fire Rush by Jacqueline Crooks (Jamaican/British) (Historical Fiction)

Fire Rush by Jacqueline Crooks (Jamaican/British) (Historical Fiction)  Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Northern Ireland) (Contemporary Fiction)

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Northern Ireland) (Contemporary Fiction) The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell (UK/Ireland) (Historical Fiction)

The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell (UK/Ireland) (Historical Fiction) Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (US) (Fan Fiction)

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (US) (Fan Fiction)

Viji Krishnamoorthy’s sweeping debut novel deftly weaves together vibrant fiction and meticulous research on the heroic exploits of Malayan wartime heroes – Sybil Kathigasu, Gurchan Singh and many others – who fearlessly fought for their beloved country.

Viji Krishnamoorthy’s sweeping debut novel deftly weaves together vibrant fiction and meticulous research on the heroic exploits of Malayan wartime heroes – Sybil Kathigasu, Gurchan Singh and many others – who fearlessly fought for their beloved country.

“Bodies of Light has been nominated by popular vote from public library staff across Victoria.” – State Library of Victoria, Australia

“Bodies of Light has been nominated by popular vote from public library staff across Victoria.” – State Library of Victoria, Australia “Daughter of the Moon Goddess is jam-packed novel that follows Xingyin on her path to self-discovery as she tries to free her mother and herself from their eternal confinement on the moon.

“Daughter of the Moon Goddess is jam-packed novel that follows Xingyin on her path to self-discovery as she tries to free her mother and herself from their eternal confinement on the moon. “This debut novel is a stunner, historical fiction at its best (captivating, illuminating and provoking) in its depiction and portrayal of the horrors of racism, discrimination, abuse and greed.

“This debut novel is a stunner, historical fiction at its best (captivating, illuminating and provoking) in its depiction and portrayal of the horrors of racism, discrimination, abuse and greed. “Kurangaituku takes readers on an immersive journey through deep time with its shape-shifting lead character. An exploration and reclamation of indigenous storytelling, it shows how language can create, shape, give life and destroy, with “one hundred lifetimes or more able to be lived by a single being.

“Kurangaituku takes readers on an immersive journey through deep time with its shape-shifting lead character. An exploration and reclamation of indigenous storytelling, it shows how language can create, shape, give life and destroy, with “one hundred lifetimes or more able to be lived by a single being. “It is a book that allows a deep insight into the daily lives of the so called ordinary people. The author treats each of them with respect and approaches with careful empathy.” – Stadtbüchereien Düsseldorf, Germany

“It is a book that allows a deep insight into the daily lives of the so called ordinary people. The author treats each of them with respect and approaches with careful empathy.” – Stadtbüchereien Düsseldorf, Germany “A fantastic (in all senses of the word) novel that somehow weaves a mystery and time travel and colonies on the moon and a pandemic and a double homicide together into a beautiful, life-affirming story.” – Winnipeg Public Library, Canada

“A fantastic (in all senses of the word) novel that somehow weaves a mystery and time travel and colonies on the moon and a pandemic and a double homicide together into a beautiful, life-affirming story.” – Winnipeg Public Library, Canada “Inni, a prostitute and drug addict, is brutally murdered in a forest. From the realm of the dead, she recounts her broken life. Rhythmically, her story returns to the end point of her existence, when the Hunter has ushered her into his car for a final journey. Carried by a powerful and poetic writing, this book sublimates the unbearable.” – Bibliothèque Municipale de Reims, France

“Inni, a prostitute and drug addict, is brutally murdered in a forest. From the realm of the dead, she recounts her broken life. Rhythmically, her story returns to the end point of her existence, when the Hunter has ushered her into his car for a final journey. Carried by a powerful and poetic writing, this book sublimates the unbearable.” – Bibliothèque Municipale de Reims, France “This was a beautifully written book that wove true historical events into a thought provoking and emotional book. The characters are fully formed and bring to life the story of turmoil, betrayal, the need for understanding and acceptance , flitting between the present day and 1970s. The Fig Tree was a particularly unique narrator – and a reminder of the impacts of war of community and nature.” – Glasgow Life, Scotland

“This was a beautifully written book that wove true historical events into a thought provoking and emotional book. The characters are fully formed and bring to life the story of turmoil, betrayal, the need for understanding and acceptance , flitting between the present day and 1970s. The Fig Tree was a particularly unique narrator – and a reminder of the impacts of war of community and nature.” – Glasgow Life, Scotland “The refugee crisis told through the eyes of a child highlights the difficult circumstances of a group of Syrians on a boat in the Mediterranean, but underscores a sense of humanism binding all people together. ” – San Diego Public Library, USA

“The refugee crisis told through the eyes of a child highlights the difficult circumstances of a group of Syrians on a boat in the Mediterranean, but underscores a sense of humanism binding all people together. ” – San Diego Public Library, USA 2020 marked the 25th anniversary of the Women’s Prize for Fiction, a feat that was celebrated by the creation of a reading challenge to read all the winners including last year’s Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell.

2020 marked the 25th anniversary of the Women’s Prize for Fiction, a feat that was celebrated by the creation of a reading challenge to read all the winners including last year’s Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell.

Summer by Ali Smith (British)- In the present, Sacha knows the world’s in trouble. Her brother Robert just is trouble. Their mother and father are having trouble. Meanwhile the world’s in meltdown – and the real meltdown hasn’t even started yet. In the past, a lovely summer. A different brother and sister know they’re living on borrowed time. This is a story about people on the brink of change. They’re family, but they think they’re strangers. So: where does family begin? And what do people who think they’ve got nothing in common have in common?

Summer by Ali Smith (British)- In the present, Sacha knows the world’s in trouble. Her brother Robert just is trouble. Their mother and father are having trouble. Meanwhile the world’s in meltdown – and the real meltdown hasn’t even started yet. In the past, a lovely summer. A different brother and sister know they’re living on borrowed time. This is a story about people on the brink of change. They’re family, but they think they’re strangers. So: where does family begin? And what do people who think they’ve got nothing in common have in common? Detransition Baby by Torrey Peters (American)- Reese nearly had it all: a loving relationship with Amy, an apartment in New York, a job she didn’t hate. She’d scraped together a life previous generations of trans women could only dream of; the only thing missing was a child. Then everything fell apart and three years on Reese is still in self-destruct mode, avoiding her loneliness by sleeping with married men.

Detransition Baby by Torrey Peters (American)- Reese nearly had it all: a loving relationship with Amy, an apartment in New York, a job she didn’t hate. She’d scraped together a life previous generations of trans women could only dream of; the only thing missing was a child. Then everything fell apart and three years on Reese is still in self-destruct mode, avoiding her loneliness by sleeping with married men. Nothing But Blue Sky by Kathleen McMahon (Ireland) – Is there such a thing as a perfect marriage?

Nothing But Blue Sky by Kathleen McMahon (Ireland) – Is there such a thing as a perfect marriage? Consent by Annabel Lyon (Canada) – Saskia and Jenny are twins, alike in appearance only: Saskia has a single-minded focus on her studies, while Jenny is glamorous, thrill-seeking and capricious. Still, when Jenny is severely injured in an accident, Saskia puts her life on hold for her sister. Sara and Mattie are sisters with another difficult dynamic: Mattie needs almost full-time care, while Sara loves nothing more than fine wines, perfumes and expensive clothing, and leaves home at the first opportunity. But when their mother dies, Sara must move Mattie in with her. Gradually, Sara and Saskia learn that both their sisters’ lives, and indeed their own, have been altered by the devastating actions of one man…

Consent by Annabel Lyon (Canada) – Saskia and Jenny are twins, alike in appearance only: Saskia has a single-minded focus on her studies, while Jenny is glamorous, thrill-seeking and capricious. Still, when Jenny is severely injured in an accident, Saskia puts her life on hold for her sister. Sara and Mattie are sisters with another difficult dynamic: Mattie needs almost full-time care, while Sara loves nothing more than fine wines, perfumes and expensive clothing, and leaves home at the first opportunity. But when their mother dies, Sara must move Mattie in with her. Gradually, Sara and Saskia learn that both their sisters’ lives, and indeed their own, have been altered by the devastating actions of one man… No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood – (American) A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to her adoring fans, her entire existence overwhelmed by the internet – or what she terms ‘the portal’. Are we in hell? the people of the portal ask themselves. Are we all just going to keep doing this until we die? Suddenly, two texts from her mother pierce the fray: ‘Something has gone wrong’ and ‘How soon can you get here?’

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood – (American) A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to her adoring fans, her entire existence overwhelmed by the internet – or what she terms ‘the portal’. Are we in hell? the people of the portal ask themselves. Are we all just going to keep doing this until we die? Suddenly, two texts from her mother pierce the fray: ‘Something has gone wrong’ and ‘How soon can you get here?’ How The One Armed Sister Sweeps Her House by Cherie Jones (Barbados) – In Baxter’s Beach, Barbados, Lala’s grandmother Wilma tells the story of the one-armed sister, a cautionary tale about what happens to girls who disobey their mothers. For Wilma, it’s the story of a wilful adventurer, who ignores the warnings of those around her, and suffers as a result.

How The One Armed Sister Sweeps Her House by Cherie Jones (Barbados) – In Baxter’s Beach, Barbados, Lala’s grandmother Wilma tells the story of the one-armed sister, a cautionary tale about what happens to girls who disobey their mothers. For Wilma, it’s the story of a wilful adventurer, who ignores the warnings of those around her, and suffers as a result.

Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller (British) – What if the life you have always known is taken from you in an instant? What would you do to get it back? Twins Jeanie and Julius have always been different from other people. At 51 years old, they still live with their mother, Dot, in rural isolation and poverty. Inside the walls of their old cottage they make music, and in the garden they grow (and sometimes kill) everything they need for sustenance.

Unsettled Ground by Claire Fuller (British) – What if the life you have always known is taken from you in an instant? What would you do to get it back? Twins Jeanie and Julius have always been different from other people. At 51 years old, they still live with their mother, Dot, in rural isolation and poverty. Inside the walls of their old cottage they make music, and in the garden they grow (and sometimes kill) everything they need for sustenance. Because Of You by Dawn French (British) – Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock . . . midnight.

Because Of You by Dawn French (British) – Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock . . . midnight. Small Pleasures by Clare Chambers (British) – 1957, the suburbs of South East London. Jean Swinney is a journalist on a local paper, trapped in a life of duty and disappointment from which there is no likelihood of escape.

Small Pleasures by Clare Chambers (British) – 1957, the suburbs of South East London. Jean Swinney is a journalist on a local paper, trapped in a life of duty and disappointment from which there is no likelihood of escape. Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (British) – Piranesi lives in the House.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (British) – Piranesi lives in the House. The Golden Rule by Amanda Craig (British) – Intelligent, bookish and hard-working, Hannah is part of a generation that grew up in hope and has tried to escape life in Cornwall’s ugliest coastal town through a university degree, a professional career, and marriage to the privileged Jake. However, her life has gone disastrously wrong. Jake has left her for Eve and, reduced to near penury, she is desperate enough to agree to murder the brutal husband of Jinni, the rich woman she meets in the First Class carriage of the London to Penzance train, in return for having Jake killed.

The Golden Rule by Amanda Craig (British) – Intelligent, bookish and hard-working, Hannah is part of a generation that grew up in hope and has tried to escape life in Cornwall’s ugliest coastal town through a university degree, a professional career, and marriage to the privileged Jake. However, her life has gone disastrously wrong. Jake has left her for Eve and, reduced to near penury, she is desperate enough to agree to murder the brutal husband of Jinni, the rich woman she meets in the First Class carriage of the London to Penzance train, in return for having Jake killed. Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan (Ireland) – When you leave Ireland aged 22 to spend your parents’ money, it’s called a gap year. When Ava leaves Ireland aged 22 to make her own money, she’s not sure what to call it, but it involves:

Exciting Times by Naoise Dolan (Ireland) – When you leave Ireland aged 22 to spend your parents’ money, it’s called a gap year. When Ava leaves Ireland aged 22 to make her own money, she’s not sure what to call it, but it involves: Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi (American) – In her youth, Tara was wild. She abandoned her arranged marriage to join an ashram, took a hapless artist for a lover, rebelled against every social expectation of a good Indian woman – all with her young child in tow.

Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi (American) – In her youth, Tara was wild. She abandoned her arranged marriage to join an ashram, took a hapless artist for a lover, rebelled against every social expectation of a good Indian woman – all with her young child in tow. Luster by Raven Leilani (American) – Edie is just trying to survive. She’s messing up in her dead-end admin job in her all white office, is sleeping with all the wrong men, and has failed at the only thing that meant anything to her, painting. No one seems to care that she doesn’t really know what she’s doing with her life beyond looking for her next hook-up.

Luster by Raven Leilani (American) – Edie is just trying to survive. She’s messing up in her dead-end admin job in her all white office, is sleeping with all the wrong men, and has failed at the only thing that meant anything to her, painting. No one seems to care that she doesn’t really know what she’s doing with her life beyond looking for her next hook-up. In the first of so many I still owe thank you’s to, I would like to say a heart-felt public thank you to a woman who makes magic with words, author

In the first of so many I still owe thank you’s to, I would like to say a heart-felt public thank you to a woman who makes magic with words, author

Translated Fiction

Translated Fiction

Today the short list was announced for the woman’s prize for fiction. From the

Today the short list was announced for the woman’s prize for fiction. From the

Meena Kandasamy, When I Hit You: Or, A Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife –

Meena Kandasamy, When I Hit You: Or, A Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife –  Kamila Shamsie, Home Fire –

Kamila Shamsie, Home Fire –  Jesmyn Ward, Sing, Unburied, Sing –

Jesmyn Ward, Sing, Unburied, Sing –  Imogen Hermes Gowar, The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock

Imogen Hermes Gowar, The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock

This is what appealed to me immediately about the prospect of reading Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu. It promises to do the same thing, to take the reader from where we are at today in a culture and link it back to the past, from modern day Uganda to the era of when the region was ruled as a kingdom. And it succeeds brilliantly, in a way rarely seen in literature in the UK/US published today.

This is what appealed to me immediately about the prospect of reading Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu. It promises to do the same thing, to take the reader from where we are at today in a culture and link it back to the past, from modern day Uganda to the era of when the region was ruled as a kingdom. And it succeeds brilliantly, in a way rarely seen in literature in the UK/US published today.

Some are haunted by ghosts of the past, thinking themselves not of sound mind, particularly when aspects of their childhood have been hidden from them, some have prophetic dreams, some have had a foreign university education and try to sever their connections to the old ways, though continue to be haunted by omens and symbols, making it difficult to ignore what they feel within themselves, that their mind wishes to reject. Some turn to God and the Awakened, looking for salvation in newly acquired religions.

Some are haunted by ghosts of the past, thinking themselves not of sound mind, particularly when aspects of their childhood have been hidden from them, some have prophetic dreams, some have had a foreign university education and try to sever their connections to the old ways, though continue to be haunted by omens and symbols, making it difficult to ignore what they feel within themselves, that their mind wishes to reject. Some turn to God and the Awakened, looking for salvation in newly acquired religions.

This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness.

This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness. It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s

It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s  Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.

Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.