I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style.

I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style.

It was also the first work of fiction I have read, after a nine week pause, while I have been working on my own writing project, so its style of short well spaced paragraphs, really suited me. I highlighted hundreds of passages, an indicative sign.

Change. Unlearning yourself is more important than knowing yourself.

It was helpful to listen to the recent Charco Press interview linked below to understand that it is a kind of anti-hero story, inspired by her thinking about The Odyssey’s Penelope while her lover Odysseus is off on his hero’s quest – of the inner journey of the one who waits, the way that quiet contemplation and observation also reveal understanding and epiphanies.

Odysseus, he of the many twists and turns. Penelope, she of the many twists and turns without moving from her armchair. Weaving the notebook by day, unravelling it by night.

The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother.

The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother.

His absence coincides with her recovery from an accident, so she has a double experience of waiting, a greater opportunity to observe the familiar and unfamiliar around her, to see patterns, imagine connections, dream and catastrophise.

Childhood is so uncertain, so distant. It’s almost like childhood is the origin of fiction: describing any past event over and over to see how far away you are getting from reality.

And then there is her quiet obsession with notebooks, with the ideal notebook, another subject that evolves in her pursuit of it. It’s thought provoking, funny, full of lots of literary and musical references, which I enjoyed listening to while reading and quite unlike anything else I’ve read. And a nod to Proust. The dude.

I was left with a scar. I think telling stories is a way of putting a scar into words. Since not all blows or falls leave marks, the words are there, ready to be put together in different ways, anywhere, anytime, in response to any fall, however serious or slight.

Random observations over time create patterns and themes, eliciting minor epiphanies.

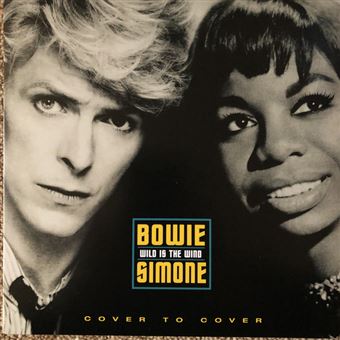

A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both David Bowie and Nina Simone, Wild is the Wind.

A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both David Bowie and Nina Simone, Wild is the Wind.

…the present is also, as its name suggests, a gift. It doesn’t suggest longing or loss. It’s just a present, a gift, a time with no strings attached which is totally ours, to use however we want, however we please. There are days when I find the future overwhelming, with all the bright lights and commotion.

I highly recommend it if you enjoy plotless narratives that make you think and see meaning in the ordinary. And relate to the little things.

Dwarf things. Small things. Little things in relation to the norm. Insignificant things. Things with different dimensions. Curiously, the stories I like the most are made up of trivialities. Details. Trifles. These days, people look to what’s big. The big picture, big sales figures, success. Bright lights, interviews, breaking news. Whatever’s famous. Importance judged by fame. Maybe small things are subversive. Living on a modest scale compared to the norm. Maybe the dwarf is the hero of our time.

Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981.

Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981.

Her novels include Todo nada (2009), Cuaderno ideal (2014) published in English as Loop and the storybook Cómo piensan las piedras (2017). Her most recent novel is Brujas (2020).

Brenda Lozano was recognized by Conaculta, Hay Festival and the British Council as one of the most important writers under 40 years of age in Mexico and named as one of the Bogotá 39, a selection of the best young writers in Latin America. She also writes for the newspaper El País.

Further Information

On Charco Press’s Instagram IGTV page there is a video interview with Brenda Lozano for WIT Month where she speaks about the process of translation as a part of the art of writing, about her influences as she wrote Loop and about how she has taken the story of Penelope and Odysseus as inspiration.

Don’t be alarmed if this isn’t going anywhere. Don’t expect theories, reliable facts or conclusions. Don’t take any of this too seriously. That’s what universities are for, and theses, and academic studies. Personally, I like cafés, bars and living rooms. Not to mention comfortable cushions. So nice and cosy.

My final read of August for WITMonth was The Party Wall, French Canadian author Catherine Leroux’s third novel. It was shortlisted for the

My final read of August for WITMonth was The Party Wall, French Canadian author Catherine Leroux’s third novel. It was shortlisted for the

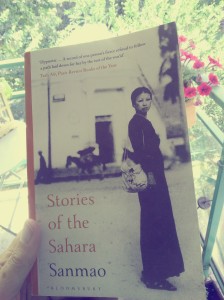

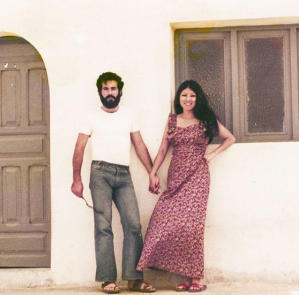

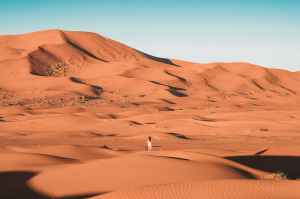

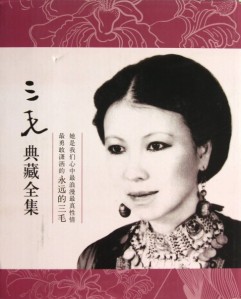

The last nonfiction book I read was also set in Morocco (at the time referred to as the Spanish Sahara) written by a foreign woman living openly with her boyfriend, it couldn’t be more in contrast with what I’ve just read here – although Sanmao does encounter women living within the oppressive system that is at work in this collection.

The last nonfiction book I read was also set in Morocco (at the time referred to as the Spanish Sahara) written by a foreign woman living openly with her boyfriend, it couldn’t be more in contrast with what I’ve just read here – although Sanmao does encounter women living within the oppressive system that is at work in this collection.

Naondel is the name of the ship that will bring the First Women to the island of Menos.

Naondel is the name of the ship that will bring the First Women to the island of Menos. The darkness these women endure, the evil that is perpetuated by their ruler, is only alleviated by the foreknowledge that we already know these women will eventually escape it. So we read in anticipation of that event, in the meantime getting to know each of them and the powers they had before they were enslaved.

The darkness these women endure, the evil that is perpetuated by their ruler, is only alleviated by the foreknowledge that we already know these women will eventually escape it. So we read in anticipation of that event, in the meantime getting to know each of them and the powers they had before they were enslaved. Red Abbey is situated on the island Menos, run by women, a kind of educational refuge that has elements of sounding like a boarding school and a convent. On the mainland some are not even sure if it is myth or reality, but they send their girls there in hope that the rumours are trues. We learn that Maresi was sent there by her family during ‘Hunger Winter’ and that the abundance of food, the genuine care and education she is given makes it a place she adores.

Red Abbey is situated on the island Menos, run by women, a kind of educational refuge that has elements of sounding like a boarding school and a convent. On the mainland some are not even sure if it is myth or reality, but they send their girls there in hope that the rumours are trues. We learn that Maresi was sent there by her family during ‘Hunger Winter’ and that the abundance of food, the genuine care and education she is given makes it a place she adores. There are two maps at the front of the book, one of Red Abbey, a walled area showing various buildings, such as Novice House, Knowledge House, Body’s Spring, Temple of the Rose, named steps and courtyards and a map of the island drawn by ‘Sister 0 in the second year of the reign of our thirty-second mother, based on the original by ‘Garai of the Blood in the reign of First Mother’

There are two maps at the front of the book, one of Red Abbey, a walled area showing various buildings, such as Novice House, Knowledge House, Body’s Spring, Temple of the Rose, named steps and courtyards and a map of the island drawn by ‘Sister 0 in the second year of the reign of our thirty-second mother, based on the original by ‘Garai of the Blood in the reign of First Mother’

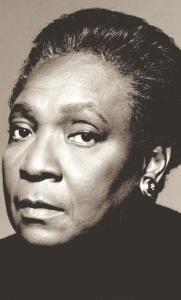

Maryse Condé is one of my favourite authors and I’ve been slowly working my way through her books since she was nominated for the

Maryse Condé is one of my favourite authors and I’ve been slowly working my way through her books since she was nominated for the

Usually when I come across a new book that sounds like my kind of read, meaning it is of cross-cultural interest, where a character (or person) from one culture (preferably not one I’m familiar with) encounters another, I’ll find others who’ve read it to discern whether it’s for me or not.

Usually when I come across a new book that sounds like my kind of read, meaning it is of cross-cultural interest, where a character (or person) from one culture (preferably not one I’m familiar with) encounters another, I’ll find others who’ve read it to discern whether it’s for me or not.

I absolutely loved Stories of the Sahara, in its entirety and it will likely be my favourite nonfiction title of the year. It is so refreshing to read a travelogue by a woman from another culture and discover a writer beloved of Chinese and Taiwanese readers for decades.

I absolutely loved Stories of the Sahara, in its entirety and it will likely be my favourite nonfiction title of the year. It is so refreshing to read a travelogue by a woman from another culture and discover a writer beloved of Chinese and Taiwanese readers for decades. The combination of her naivete, determination and feminism – her refusal to be stopped from doing what she wants – create some of the most hilarious and alarming moments. Her kindness and frankness gain her entry inside the culture and landscape, providing insights few are capable of accessing. People trusted her – yes they often took advantage of her – but she was a willing participant. They provided rich literary material, clearly!

The combination of her naivete, determination and feminism – her refusal to be stopped from doing what she wants – create some of the most hilarious and alarming moments. Her kindness and frankness gain her entry inside the culture and landscape, providing insights few are capable of accessing. People trusted her – yes they often took advantage of her – but she was a willing participant. They provided rich literary material, clearly!

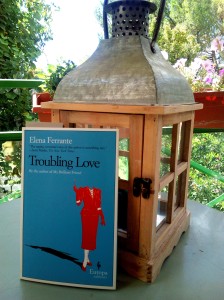

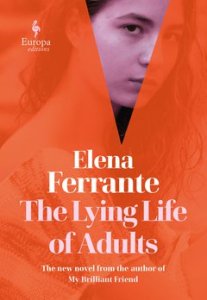

That’s Ferrante.

That’s Ferrante.

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

Evangalising Across the Argentinian Countryside

Evangalising Across the Argentinian Countryside