translated by Sophie Lewis (from French)

Reality bites.

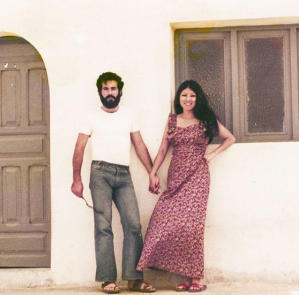

The last nonfiction book I read was also set in Morocco (at the time referred to as the Spanish Sahara) written by a foreign woman living openly with her boyfriend, it couldn’t be more in contrast with what I’ve just read here – although Sanmao does encounter women living within the oppressive system that is at work in this collection.

The last nonfiction book I read was also set in Morocco (at the time referred to as the Spanish Sahara) written by a foreign woman living openly with her boyfriend, it couldn’t be more in contrast with what I’ve just read here – although Sanmao does encounter women living within the oppressive system that is at work in this collection.

In Morocco the ban on ‘fornication’, or zina, isn’t just a moral injunction. Article 490 of the penal code prescribes ‘imprisonment of between one month and one year [for] all persons of opposite sexes, who, not being united by the bonds of marriage, pursue sexual relations’. According to article 489, all ‘preferential or unnatural behaviour between two persons of the same sex will be punished by between six months and three years’ imprisonment’.

Leïla Slimani interviews women who responded to her after the publication of her first novel Adèle, a character she describes as a rather extreme metaphor for the sexual experience of young Moroccan women; it was a book that provoked a dialogue, many women wanted to have that conversation with her, felt safe doing so, inspiring her to collect those stories and publish them for that reason, to provoke a national conversation.

Novels have a magical way of forging a very intimate connection between writers and their readers, of toppling the barriers of shame and mistrust. My hours with those women were very special. And it’s their stories I have tried to give back: the impassioned testimonies of a time and its suffering.

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Pexels.com

In these essays Leila Slimani gives a voice to Moroccan women trying to live lives where they can express their natural affinity for love, while living in a culture that both condemns and commodifies sex, where the law punishes and outlaws sex outside marriage, as well as homosexuality and prostitution. The consequences are a unique form of extreme and give rise to behaviours that shock.

It’s both a discomforting read, to encounter this knowledge and hear this testimony for the first time, and encouraging if it means that a space is being created that allows the conversation to happen at all.

However, overall it leaves a heavy feeling of disempowerment, having glimpsed the tip of another nation’s patriarchal iceberg. We are left with the feeling that this is a steep and icy behemoth to conquer. Article 489 is not drawn from sharia or any other religious source, it is in fact identical to the French penal code’s former article 331, repealed in 1982. They are laws inherited directly from the French protectorate.

In a conversation with Egyptian feminist and author Mona Eltahawy about the tussle between the freedom desired and the shackles forced upon women, Eltahawy responded by using words attributed to the great American abolitionist Harriet Tubman, who devoted her life to persuading slaves to flee the plantations and claim their freedom.

She is meant to have said: “I freed a thousand slaves. I could have freed a thousand more if only they knew were slaves.” Emancipation, Eltahawy told me, is first about raising awareness. If women haven’t fully understood the state of inferiority in which they are kept, they will do nothing but perpetuate it.

Women are stepping out of isolation and sharing their stories everywhere, finding solidarity in that first step, sharing in a safe space, being heard, realising they are not alone.

May it be a stepping stone to change.

I read this book as part of WIT (Women in Translation) month and was fortunate to have been gifted it by a reader, since I participated in the gift swap, so thank you Jess for sending me this book, you can read her review of it on her blog, Around The World One Female Novelist at a Time.

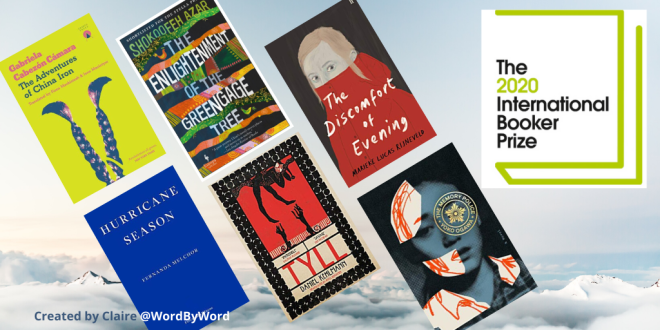

Jas lives with her devout farming family in the rural Netherlands. One winter’s day, her older brother joins an ice skating trip. Resentful at being left alone, she makes a perverse plea to God; he never returns. As grief overwhelms the farm, Jas succumbs to a vortex of increasingly disturbing fantasies, watching her family disintegrate into a darkness that threatens to derail them all.

Jas lives with her devout farming family in the rural Netherlands. One winter’s day, her older brother joins an ice skating trip. Resentful at being left alone, she makes a perverse plea to God; he never returns. As grief overwhelms the farm, Jas succumbs to a vortex of increasingly disturbing fantasies, watching her family disintegrate into a darkness that threatens to derail them all. Listening to the author read in Dutch was wonderful and the discussion between the judge, the translator and author worth listening to and may well influence more to discover what the book is about.

Listening to the author read in Dutch was wonderful and the discussion between the judge, the translator and author worth listening to and may well influence more to discover what the book is about. Naondel is the name of the ship that will bring the First Women to the island of Menos.

Naondel is the name of the ship that will bring the First Women to the island of Menos. The darkness these women endure, the evil that is perpetuated by their ruler, is only alleviated by the foreknowledge that we already know these women will eventually escape it. So we read in anticipation of that event, in the meantime getting to know each of them and the powers they had before they were enslaved.

The darkness these women endure, the evil that is perpetuated by their ruler, is only alleviated by the foreknowledge that we already know these women will eventually escape it. So we read in anticipation of that event, in the meantime getting to know each of them and the powers they had before they were enslaved. Red Abbey is situated on the island Menos, run by women, a kind of educational refuge that has elements of sounding like a boarding school and a convent. On the mainland some are not even sure if it is myth or reality, but they send their girls there in hope that the rumours are trues. We learn that Maresi was sent there by her family during ‘Hunger Winter’ and that the abundance of food, the genuine care and education she is given makes it a place she adores.

Red Abbey is situated on the island Menos, run by women, a kind of educational refuge that has elements of sounding like a boarding school and a convent. On the mainland some are not even sure if it is myth or reality, but they send their girls there in hope that the rumours are trues. We learn that Maresi was sent there by her family during ‘Hunger Winter’ and that the abundance of food, the genuine care and education she is given makes it a place she adores. There are two maps at the front of the book, one of Red Abbey, a walled area showing various buildings, such as Novice House, Knowledge House, Body’s Spring, Temple of the Rose, named steps and courtyards and a map of the island drawn by ‘Sister 0 in the second year of the reign of our thirty-second mother, based on the original by ‘Garai of the Blood in the reign of First Mother’

There are two maps at the front of the book, one of Red Abbey, a walled area showing various buildings, such as Novice House, Knowledge House, Body’s Spring, Temple of the Rose, named steps and courtyards and a map of the island drawn by ‘Sister 0 in the second year of the reign of our thirty-second mother, based on the original by ‘Garai of the Blood in the reign of First Mother’

Maryse Condé is one of my favourite authors and I’ve been slowly working my way through her books since she was nominated for the

Maryse Condé is one of my favourite authors and I’ve been slowly working my way through her books since she was nominated for the

Usually when I come across a new book that sounds like my kind of read, meaning it is of cross-cultural interest, where a character (or person) from one culture (preferably not one I’m familiar with) encounters another, I’ll find others who’ve read it to discern whether it’s for me or not.

Usually when I come across a new book that sounds like my kind of read, meaning it is of cross-cultural interest, where a character (or person) from one culture (preferably not one I’m familiar with) encounters another, I’ll find others who’ve read it to discern whether it’s for me or not.

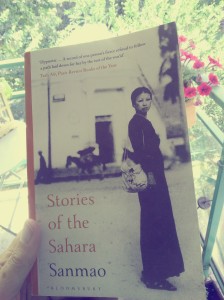

I absolutely loved Stories of the Sahara, in its entirety and it will likely be my favourite nonfiction title of the year. It is so refreshing to read a travelogue by a woman from another culture and discover a writer beloved of Chinese and Taiwanese readers for decades.

I absolutely loved Stories of the Sahara, in its entirety and it will likely be my favourite nonfiction title of the year. It is so refreshing to read a travelogue by a woman from another culture and discover a writer beloved of Chinese and Taiwanese readers for decades. The combination of her naivete, determination and feminism – her refusal to be stopped from doing what she wants – create some of the most hilarious and alarming moments. Her kindness and frankness gain her entry inside the culture and landscape, providing insights few are capable of accessing. People trusted her – yes they often took advantage of her – but she was a willing participant. They provided rich literary material, clearly!

The combination of her naivete, determination and feminism – her refusal to be stopped from doing what she wants – create some of the most hilarious and alarming moments. Her kindness and frankness gain her entry inside the culture and landscape, providing insights few are capable of accessing. People trusted her – yes they often took advantage of her – but she was a willing participant. They provided rich literary material, clearly!

That’s Ferrante.

That’s Ferrante.

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

Evangalising Across the Argentinian Countryside

Evangalising Across the Argentinian Countryside

The opening sentence introduces us to the birth of a poverty-stricken community, one that will rise up despite numerous efforts to destroy it. As more displaced people hear of them, it continues to reassemble, grow, and become occupied by the marginalised, who do what they can to get ahead.

The opening sentence introduces us to the birth of a poverty-stricken community, one that will rise up despite numerous efforts to destroy it. As more displaced people hear of them, it continues to reassemble, grow, and become occupied by the marginalised, who do what they can to get ahead.