Elif Shafak is one of my favourite writers, ever since being lent The Bastard of Istanbul (2006) and then on learning she had been a Rumi scholar, was delighted to read The Forty Rules of Love (2009).

She is one of the most interesting and prolific authors of cross-cultural fiction, and made the transition in 2004 from writing in Turkish and being translated into English, to writing directly in the English language. She made the decision to write in English to have distance and freedom from political and social pressures implicated by writing in her native language, and to approach her heritage and subjects of interest from an alternative perspective.

A Profound Dedication

Her engagement in writing about social issues, multicultural and political themes and her relocation to London from Istanbul, and her deep engagement with history, identity, gender, religion and cultural themes, her regular speaking out, her weekly essays to followers and her prize nominations have all contributed to raising her profile to the point of being elected President of the Royal Society of Literature (RSL) in the UK in 2025, succeeding Bernardine Evaristo. She is a great writer and an important connector between cultures, disciplines and literary communities.

10 Minutes 38 Seconds

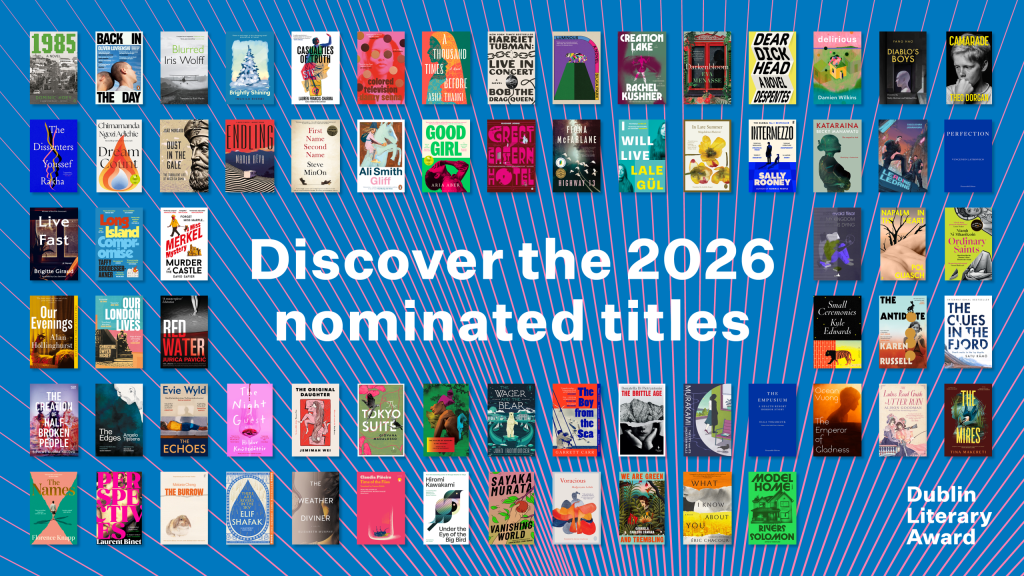

This book was shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2019, the prize that year won by Bernadine Evaristo for Girl Woman Other. I spotted this on the shelf at the library I mentioned in my last post, along with Intermezzo by Sally Rooney and The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox by Maggie O’Farrell and You Are Here by David Nicholls. I immediately jumped to read the Elif Shafak and I am happy to see there are few more of her backlist I might be able to get to this year as well.

Shafak’s novel starts with the intriguing title, what exactly is the meaning of 10 minutes and 38 seconds? The novel starts with a seven page chapter called The End. We are confronted with the early morning discovery of the body of Leila, before any of her friends have learned of her premature death/murder.

Once the authorities had identified her, she supposed they would inform her family. Her parents lived in the historic city of Van – a thousand miles away. But she did not expect them to come and fetch her dead body, considering they had rejected her long ago

You’ve brought us shame. Everyone is talking behind our backs.

So the police would have to go to her friends instead. The five of them: Sabotage Sinan, Nostalgia Nalan, Jameelah, Zaynab122, and Hollywood Humeyra.

A Post Death Structure

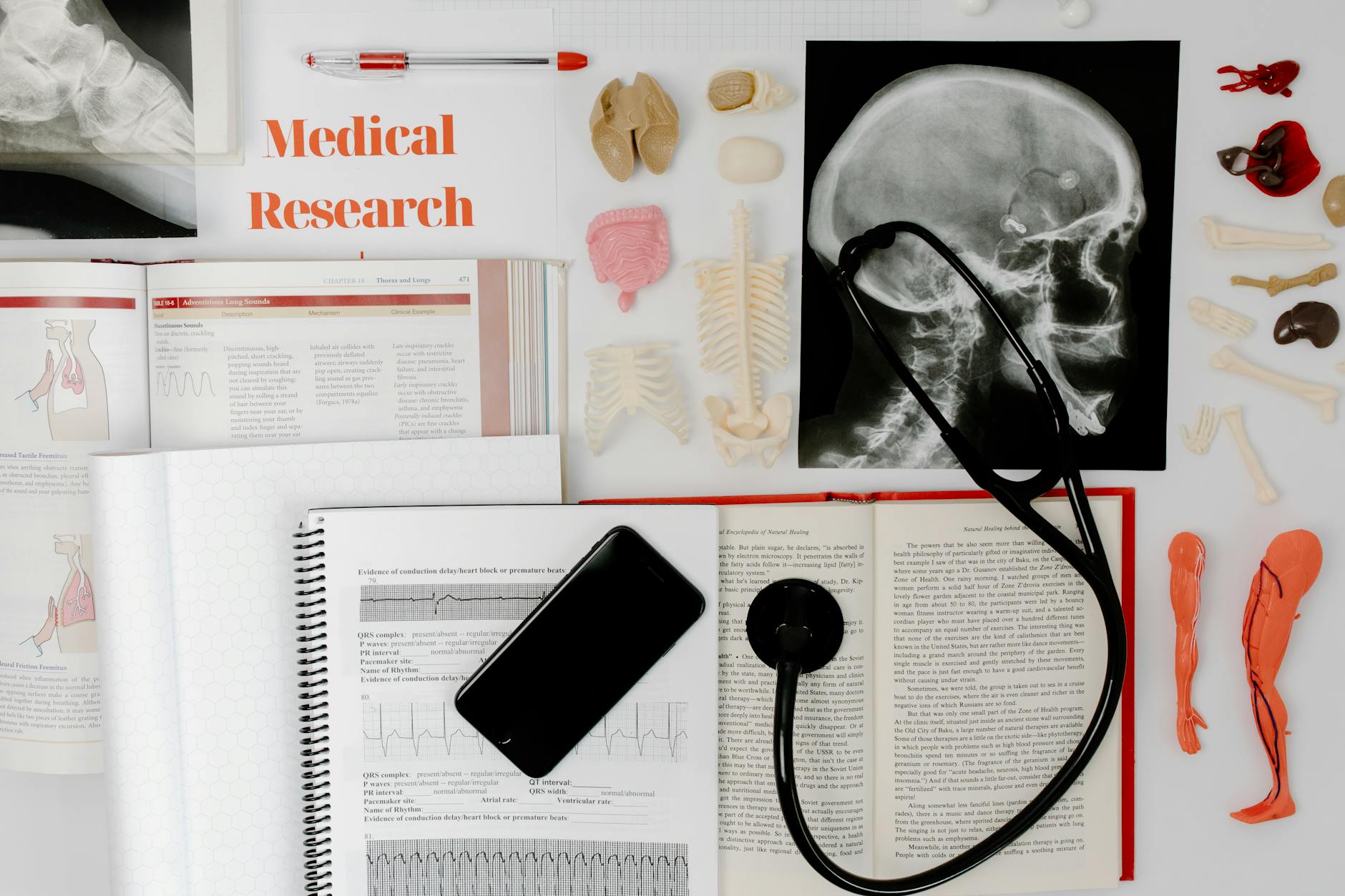

The book then is structured into, Part One: The Mind, Part Two: The Body and a very short few pages, Part Three: The Soul. In Part One we learn about the significance of the 10 minutes 38 seconds and this is what the chapters pertain to.

During this period of time when the victim is dead her consciousness is replaying memories, aromas, all of the things that she has sensed and experienced and known, and it is in these chapters that we learn about her past with her family and we are introduced to the five friends. These are the flashbacks of her life passing through her consciousness. Thus forming the structure of this first half of the novel.

Researchers at various world-renowned institutions had observed persistent brain activity in people who had just died; in some cases this had lasted for only a few minutes. In others, for as much as ten minutes and thirty eight seconds. What happened during that time? Did the dead remember the past, and, if so, which parts of it, and in what order? How could the mind condense an entire life into the time it took to boil a kettle?

As each minute passes and each sense is evoked and each friend is remembered, there is then a short story about that friend and how they came to the name they now hold and what brought them to the city of Istanbul where they all resided until this moment.

Friends on a Mission

When we get to Part Two: The Body, the consciousness has left the body and we arrive in the present moment with the five friends trying to deal with the fact that their friend is missing, is dead, and no one will allow them to visit her.

“Grief is a swallow,’ he said. ‘One day you wake up and you think it’s gone, but it’s only migrated to some other place, warming its feathers. Sooner or later, it will return and perch in your heart again.”

The want to pay their respects, to do something for her, but the city has already judged her and made decisions without the consent of family or friends, so this part of the novel becomes something of an adventure as the friends bond together to make amends for the current situation and try to do something for their dear friend. And go on a road trip in an old truck.

A Clever Structure Dulls Character Recall

The only trouble I found with the clever format of the first half, was that because it all takes place in the past and each chapter is about a different friend, by the time they all come together half way into the novel, it is not as easy to remember who they are, because they haven’t been regularly present in the text until now.

Thus it created a disconnect for this reader, who likes to imagine each character as they are introduced, but they need to stay present for that image and impression of them to last. I found that I had to refer back to the beginning to recreate that sense of the character, in order to recall who they were.

Overall I found it an enjoyable read, the characters come from all walks of life, mostly marginalised for one reason or another and in their neighbourhood they have found each other, look out for each and wish to challenge the way they and others like them are treated. By coming together to do something for Leila, they are also challenging the way their city deals with others who have been marginalised, that grief, burial, remembrance and recognition of those who have passed should be something universal that all can participate in, regardless of where life has taken them.

Nostalgia Nalan believed there were two kinds of family in this world: relatives formed the blood family; and friends, the water family. If your blood family happened to be nice and caring, you could count your lucky stars and make the most of it; and if not, there was still hope; things could take a turn for the better once you were old enough to leave your home sour home.

It’s a beautiful fable-like story, much of it inspired by real circumstances, real places and conditions and inspired by friendships lived by the author from time lived in the city of Istanbul.

Highly Recommended.

Further Reading

UnMapped Storylands: Elif Shafak’s Sunday Essays: Substack: ‘When Will You Begin That Long Journey Into Yourself?‘ Jan 11, 2026

‘I wish I could show you when you are lonely or in darkness the astonishing light of your own being.’ Hafez

Books reviewed here:

The Happiness of Blond People (2011) – A Personal Meditation on the Dangers of Identity (Essay)

Honour (2011) (Novel)

Three Daughters of Eve (2016) (Novel)

The Island of Missing Trees (2021) (Novel)

Author Elif Shafak

Elif Shafak is an award-winning British-Turkish novelist and storyteller. She has published 21 books, 13 of which are novels and her books have been translated into 58 languages.

Shafak is a Fellow and President of the Royal Society of Literature and has been chosen among BBC’s 100 most inspiring and influential women. An advocate for women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights and freedom of expression, Shafak is an inspiring public speaker and twice TED Global speaker.