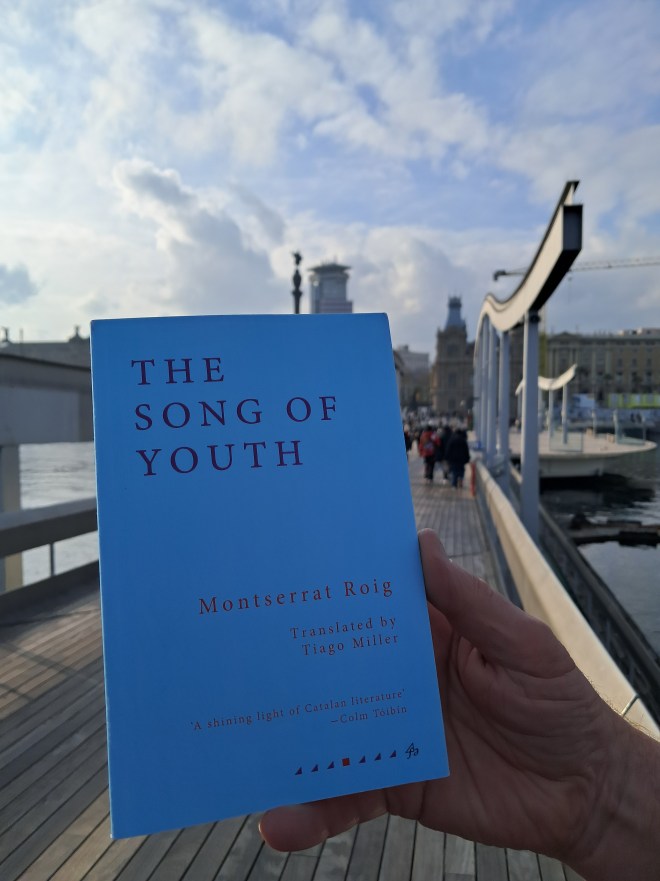

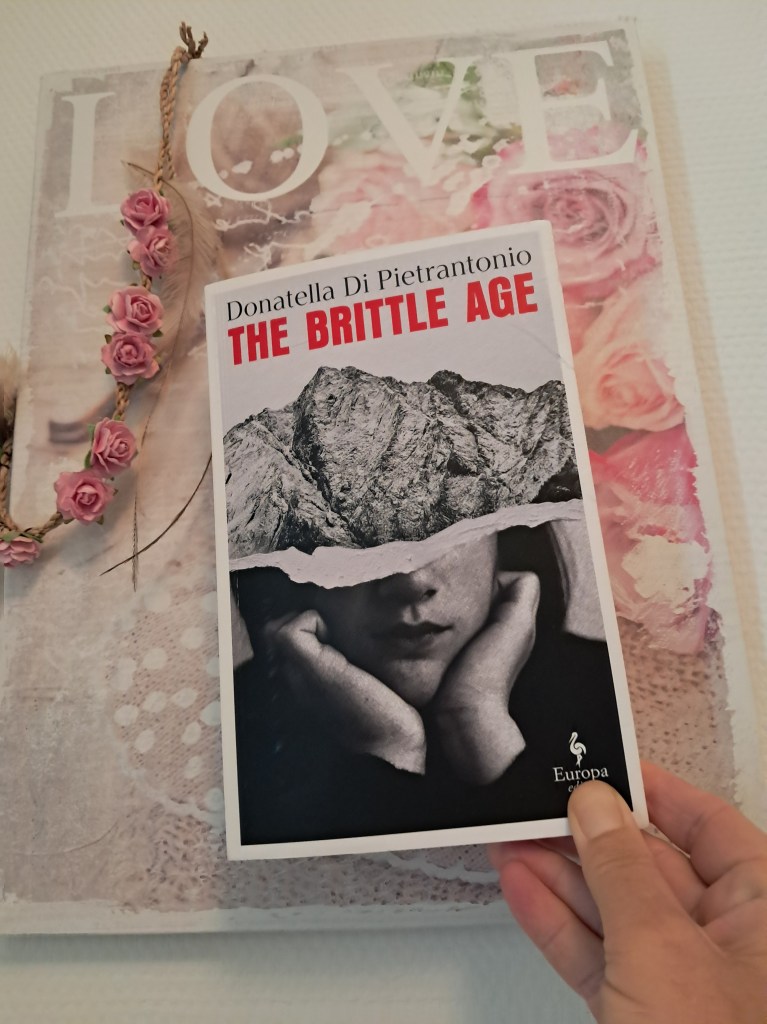

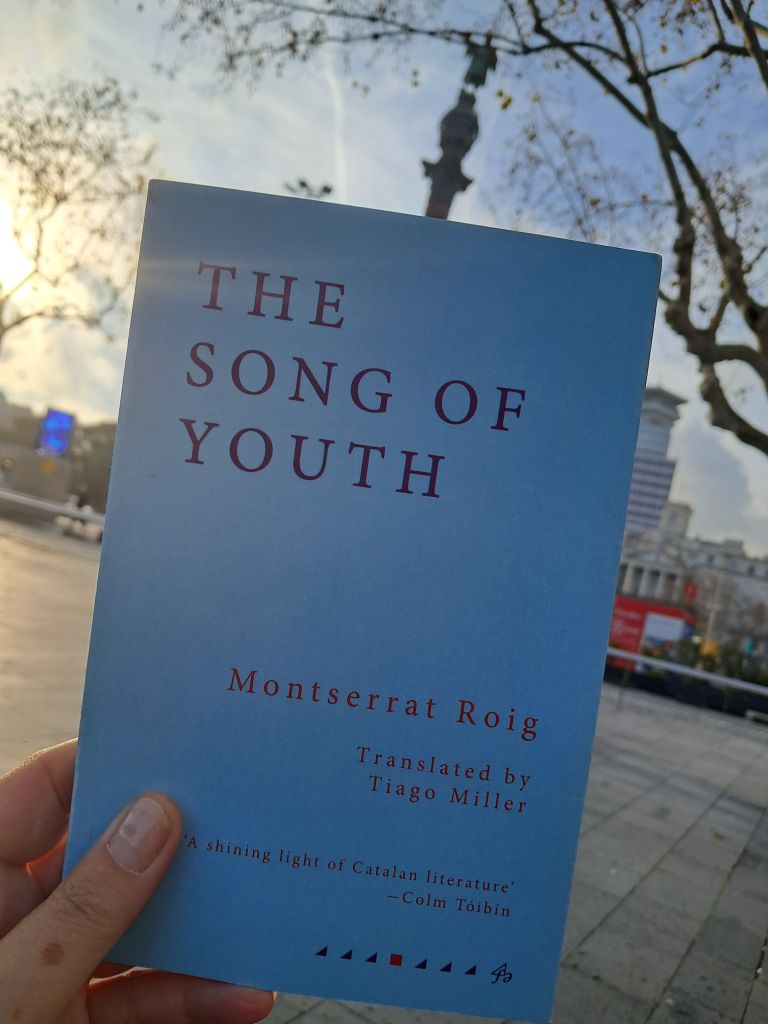

The Song of Youth ‘el cant de la joventut’ is a slim collection of short stories written by Montserrat Roig translated by Tiago Miller, published in English in 2022 by fum de stampa press (originally published in Catalan in 1989).

It was shortlisted for the 2022 Republic of Consciousness Prize, (now rebranded the Queen Mary Small Press Fiction Prize) that rewards ‘bold and innovative’ literary fiction by small presses publishing 12 or fewer titles a year that are independent of any other commercial financial entity.

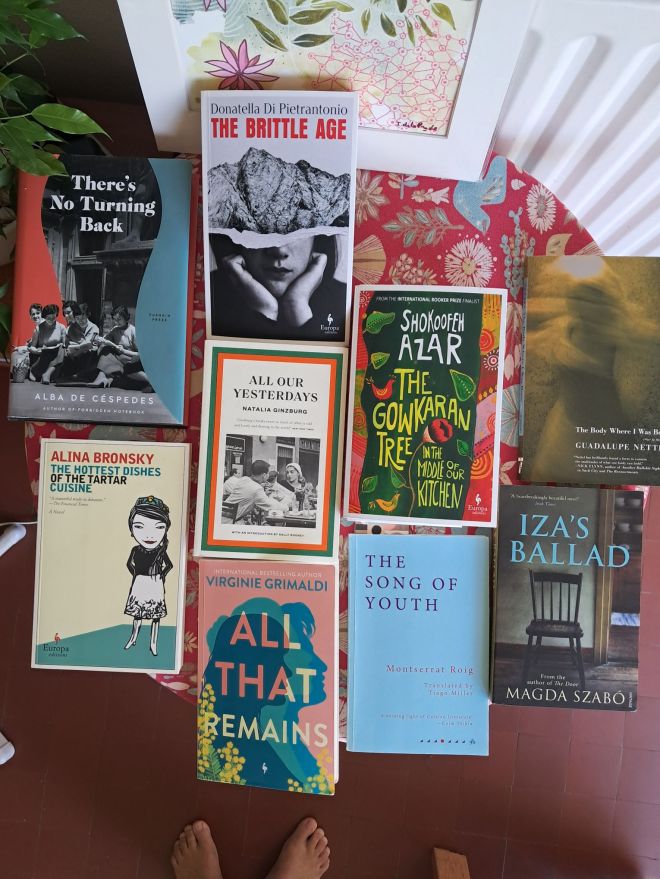

The winner of that prize in 2025 was There’s a Monster Behind the Door by Gaëlle Bélem (Ile de Reunion), translated from French by Karen Fleetwood and Laëtitia Saint-Loubert and in 2024 Of Cattle and Men (reviewed here) by Brazilian writer Ana Paula Maia, translated by Zoë Perry, published by Charco Press.

Finding and Reading Catalan literature in Catalonia

When I visited the Backstory Bookshop in Barcelona, I was interested in and looking for Catalan literature that embraced something of its history in some way.

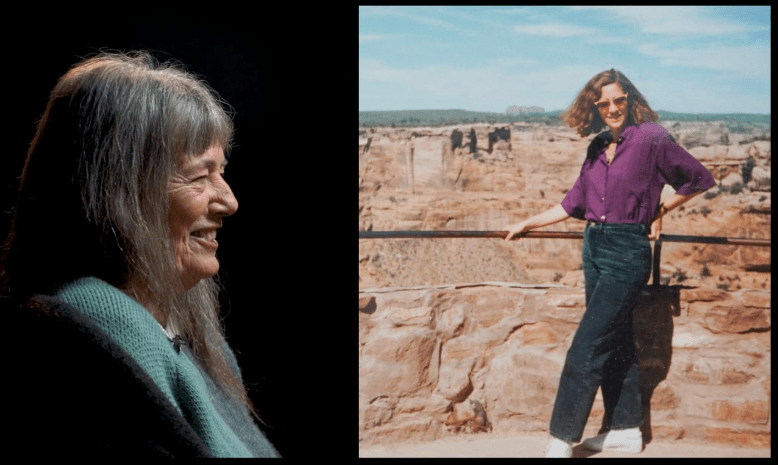

Monserrat Roig (1946-1991) was a novelist, short story writer, investigative journalist and feminist activist widely regarded as forming a central part of the Catalan canon, inspiring many other Catalonian writers to seek the intimate, personal testimonies of ordinary people, within a wider version of history guided by a strong sociopolitical engagement.

One of Roig’s many literary strengths was creating and placing subversive characters in deeply philosophical and provocative narratives, and bringing out their flawed, tender and very real aspects. It is helpful to consider this when reading her bold collection of short stories.

I’m going to mention two out of the collection that really stayed with me, The Song of Youth and Mar. Love and Ashes packs a punch, but is so short, it need not be described here.

The Song of Youth

I found it helpful to be reminded of this context, written on the back of the book.

In The Song of Youth, Montserrat Roig boldly presents eight remarkable stories that use language as a weapon against political and social “dismemory.” Her powerful and striking prose allows the important stories of those silenced by the brutal Franco regime to, at last, come to the fore. The Song of Youth is undoubtedly feminist and deeply critical but, as always, Roig’s lyrical writing gives shape, depth, and significance to the human experience.

This is how author Eva Baltasar described the collection:

The Song of Youth represents an array of lagoons in which Montserrat Roig’s most extraordinary flowers lay their roots.”

After the first reading of each story, I felt like I was sitting at the edge of one of those lagoons, firstly appreciating the flowers, though not always seeing those roots in the deep, dark depths. And so I went back and reread them. I wrote on and around the pages, and looked up the poetic literary references and was in awe.

The opening story, The Song of Youth, reread a few times, revealed its many layers with each reading. It is magnificent. I think it is a story that needs to read quietly to concentrate, like contemplating a work of art, it won’t reveal itself at a first glimpse. However, it is perfect as it is. A celebration of dying moments and the power of memory, of a life lived courageously.

I turn my face from the ominous day,

Before it comes, everlasting night,

So lifeless, it’s long since passed away.But shimmering faith renews my fight,

And I turn, with joy, towards the light,

Along galleries of deepest memory.

JOSEP CARNER, Absence

A woman lying prone in hospital with her eyes closed, near the end of her life, observes the white coat of the Doctor and has flashbacks to her youth, a stranger in a white shirt walked into the bar where she sat with her parents, with a decisive air. A transgression.

The men who came from the war didn’t have that air.

She opens her eyes, she is still alive. Everything as it was when she closed them. She knows the sounds. The sounds that keep them alive and the sounds that warn of encroaching death.

“They all died at daybreak. Just like the night.”

She is defiant. She is determined to remember a word. She succeeds.

It’s not easy to describe, this too is a story that needs to be experienced, to read the clues and the disjointed moments of the present and past that create the whole.

Death, Memory and Friendship

To Montserrat Blanes

Life has taught me to think but thinking has not taught me to live. HERZEN

The story MAR is the hardest hitting and most powerful – about a woman befriended, a relationship, admiration, of two people who are unalike but drawn towards each other, who go their own ways; until an accident changes everything.

…it never once occurred to me to give a name to that period of silence, madness and noise, to those moments when the hours would melt into timelessness and our intellectual friends, while watching us, would frown or raise an eyebrow.

“They’ve got some nerve,” said their suspicious eyes while they stared, unaware of their own fear.

The time they are together changes the one telling the story, she is an intellectual, always analysing everything, living in a world of opinions and judgments. While in this friendship, something shifts, changes her. The presence of this unconventional friend disturbed others, messing up the carefully compiled archives on their minds. From vastly different worlds, they each gain something powerful from being in each other’s lives. Something that unsettles others.

We hardly said a word, we certainly didn’t reinvent anything, but it was only with her that I lost my fear, the fear of revealing who I believe myself to be, that little girl I keep hidden in the deep, damp depths of my inner self.

A friendship of silences, commotion and madness

A tribute to friendship, this story originally published in 1989, was celebrated in December 2021 when a documentary was produced about Montserrat Roig and Montserrat Blanes friendship of silences, commotion and madness.

The audiovisual is made up of two narratives, the one in the short story and that told through the live voice and presence of Montserrat Blanes speaking from experience, memory and remembrance.

If you understand Catalan, you can watch and listen to the recording of “Roig i Blanes. Una amistat de silencis, enrenou i bogeria” on Youtube here.

Overall a powerful and thought provoking collection that makes me keen to read her longer fiction.

Further Reading

Biography: Amb uns altres ulls (With Other Eyes) by Betsabé Garcia (2016)

Article: Montserrat Roig : Up-close and from afar by Mercè Ibarz

“And when cancer attacked her, the hour of relentless truth that is illness brought out the self-portrait that the public persona had been hiding: a lucid, serene, combative writer and an excellent reader, who was cognisant of the fact that Franco’s dictatorship had pulled literary training up at its roots and who was, therefore, all too aware of her limits to that point and the power that, despite her illness, journalistic prose could give her.” Mercè Ibarz

Author, Montserrat Roig

Montserrat Roig (Barcelona, 1946-1991) was an award-winning writer and journalist, and the recipient of numerous prestigious prizes including the Premi Víctor Català and the Premi Sant Jordi.

Her journalistic work focused on forging a creative feminist tradition, and on recovering the country’s political history.

Her novels take similar stances, reflecting on the need to liberate women who were silenced by history.

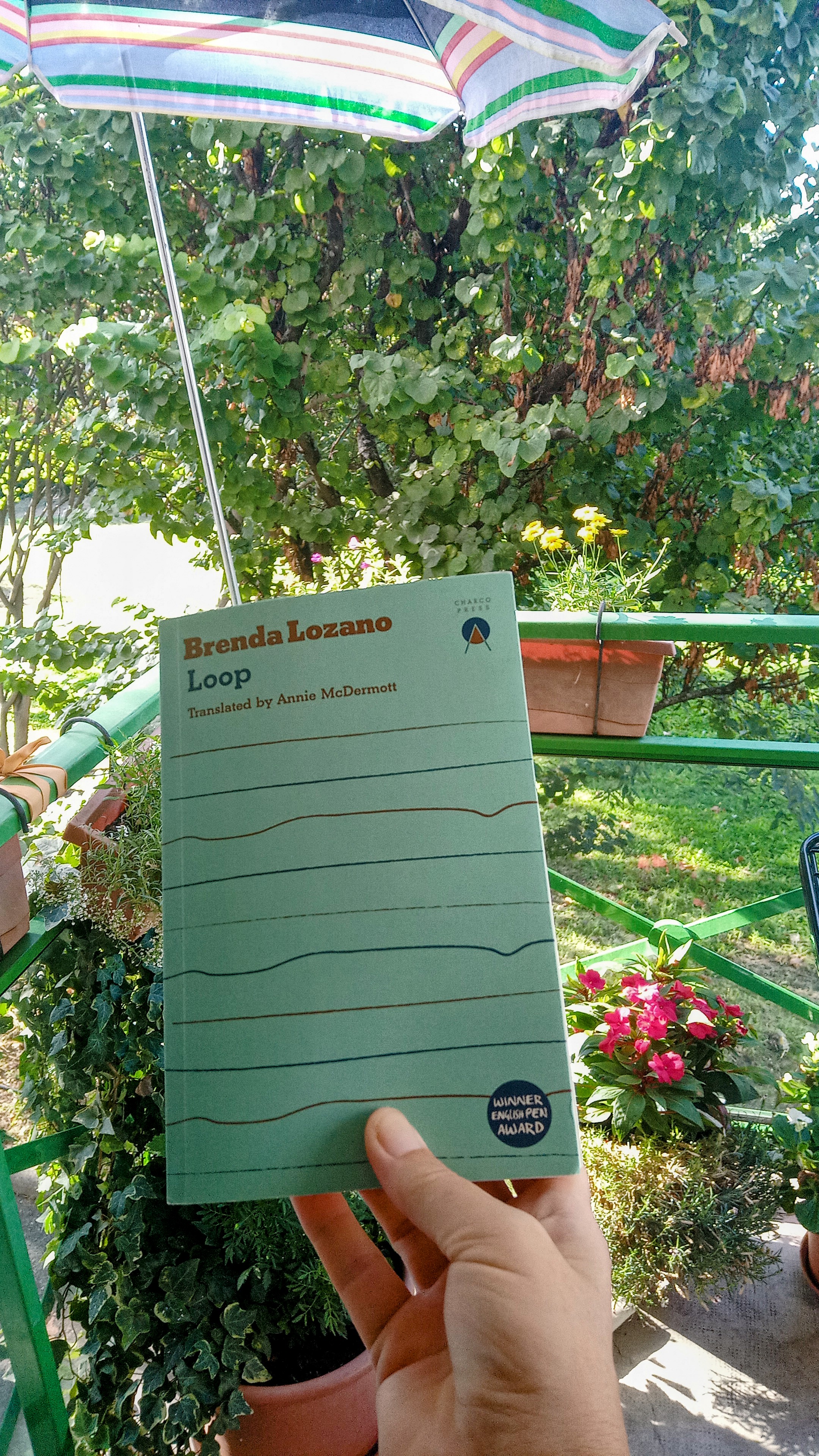

I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style.

I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style. The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother.

The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother. A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both

A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both  Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981.

Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981. The last nonfiction book I read was also set in Morocco (at the time referred to as the Spanish Sahara) written by a foreign woman living openly with her boyfriend, it couldn’t be more in contrast with what I’ve just read here – although Sanmao does encounter women living within the oppressive system that is at work in this collection.

The last nonfiction book I read was also set in Morocco (at the time referred to as the Spanish Sahara) written by a foreign woman living openly with her boyfriend, it couldn’t be more in contrast with what I’ve just read here – although Sanmao does encounter women living within the oppressive system that is at work in this collection.

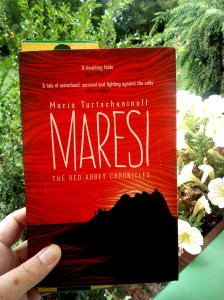

Red Abbey is situated on the island Menos, run by women, a kind of educational refuge that has elements of sounding like a boarding school and a convent. On the mainland some are not even sure if it is myth or reality, but they send their girls there in hope that the rumours are trues. We learn that Maresi was sent there by her family during ‘Hunger Winter’ and that the abundance of food, the genuine care and education she is given makes it a place she adores.

Red Abbey is situated on the island Menos, run by women, a kind of educational refuge that has elements of sounding like a boarding school and a convent. On the mainland some are not even sure if it is myth or reality, but they send their girls there in hope that the rumours are trues. We learn that Maresi was sent there by her family during ‘Hunger Winter’ and that the abundance of food, the genuine care and education she is given makes it a place she adores. There are two maps at the front of the book, one of Red Abbey, a walled area showing various buildings, such as Novice House, Knowledge House, Body’s Spring, Temple of the Rose, named steps and courtyards and a map of the island drawn by ‘Sister 0 in the second year of the reign of our thirty-second mother, based on the original by ‘Garai of the Blood in the reign of First Mother’

There are two maps at the front of the book, one of Red Abbey, a walled area showing various buildings, such as Novice House, Knowledge House, Body’s Spring, Temple of the Rose, named steps and courtyards and a map of the island drawn by ‘Sister 0 in the second year of the reign of our thirty-second mother, based on the original by ‘Garai of the Blood in the reign of First Mother’

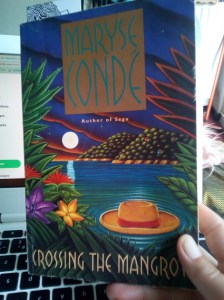

Maryse Condé is one of my favourite authors and I’ve been slowly working my way through her books since she was nominated for the

Maryse Condé is one of my favourite authors and I’ve been slowly working my way through her books since she was nominated for the

That’s Ferrante.

That’s Ferrante.