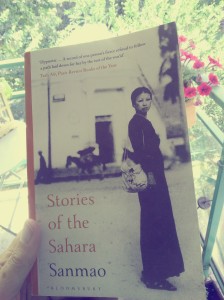

translated (from Chinese) by Mike Fu.

Literature Worthy of Translation

Usually when I come across a new book that sounds like my kind of read, meaning it is of cross-cultural interest, where a character (or person) from one culture (preferably not one I’m familiar with) encounters another, I’ll find others who’ve read it to discern whether it’s for me or not.

Usually when I come across a new book that sounds like my kind of read, meaning it is of cross-cultural interest, where a character (or person) from one culture (preferably not one I’m familiar with) encounters another, I’ll find others who’ve read it to discern whether it’s for me or not.

As soon as I saw the cover of Stories From the Sahara, I was intrigued. A fascinating and popular Taiwanese woman author of many books and essays, living in the Sahara with her Spanish lover; why has only one person I follow read this and why are we only hearing about this mysterious travel writer in 2020?

I don’t know the answer to my question (I suspect publisher’s had their radar tuned elsewhere in the past and perhaps the Anglosphere/Sinosphere head butting that takes place in the political arena affected their vision); but August is WIT (Women in Translation) month, a movement that’s gaining traction and interest, the genre and languages of books translated/published is widening and thanks to Eleanor at The Monthly Booking I bought this engaging and unforgettable read.

Thanks Mike Fu, who read the book as a young man and has translated it into English, he is now translating her next book, of their adventures in the Canary Islands.

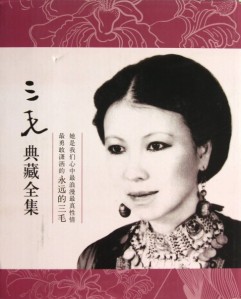

Who is Sanmao? Echo Chen? Chen Ping?

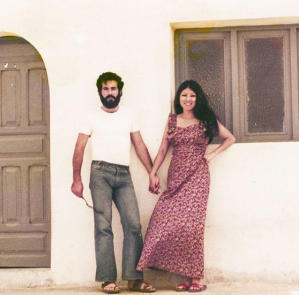

Sanmao & José, Al Aaiun, Sahara

In 1973, an independent young Chinese woman, born Chen Ping on 26 March 1943 left her family home in Taiwan, after a family tragedy, to travel to the Spanish Sahara with her friend José. They married in 1974. She had first lived in Spain in 1967 attending university in Madrid.

While in the Sahara she was inspired to write vignettes of her life there, they were published in Taiwan and China to great acclaim. The first volume debuted in May 1976.

Sanmao published more than twenty books, mostly semi-autobiographical essays, selling over fifteen million copies.

In a beautiful, moving essay, commemorating what would have been Sanmao’s 77th year, her niece Jessica Chen, remembers her Auntie, sharing something of the unique soul she was and the words of her grandparents, speaking of their tender, beloved daughter who, “had simply gotten off the train of life sooner than we expected”.

Grandpa and Grandma always said she was a special child with a gift from God, and the richness of her interior life was off-limits to others—unless she chose to let you in herself. Writing was the window she opened to the outside world. The people who understood this would naturally discover a path to her heart; those who didn’t could only stand at the window and gaze in from afar.

What was Sanmao doing in the Sahara?

Photo by Taryn Elliott on Pexels.com

One day Sanmao was absent-mindedly flipping through the pages of National Geographic when she came across a feature on the Sahara. It was from that moment that she developed an obsession not just to visit, but to live there.

I only read it through once. I couldn’t understand the feeling of homesickness that I had, inexplicable and yet so decisive, towards that vast and unfamiliar land, as if echoing from a past life.

Arriving in Spain, she learned that 280,000 square metres of the Sahara at the time were designated Spanish territory. Her desire to go there deepened, torturing her with longing.

José went ahead of her, securing a job at a phosphate mine, found them a home, allowing her to fulfill that soul-whispered desire.

Book Review – Stories of the Sahara

I absolutely loved Stories of the Sahara, in its entirety and it will likely be my favourite nonfiction title of the year. It is so refreshing to read a travelogue by a woman from another culture and discover a writer beloved of Chinese and Taiwanese readers for decades.

I absolutely loved Stories of the Sahara, in its entirety and it will likely be my favourite nonfiction title of the year. It is so refreshing to read a travelogue by a woman from another culture and discover a writer beloved of Chinese and Taiwanese readers for decades.

I almost couldn’t get over how tough it was during that initial period and thought often about heading back to Europe. Amid that endless stretch of sand, it was so hot during the day that water could scald your hands, while night was so cold that you had to wear a heavy coat. Many times I asked myself why I insisted on staying here. Why had I wanted to come to this long-forgotten corner of the world all by myself? As there were no answers to these questions, I continued to settle in, one day at a time.

I hadn’t expected it to be so funny, so many of her observations and the things requested of her made me laugh out loud. It’s unlike any other travel memoir I’ve read; here is a sensitive, empathetic woman, bringing a completely fresh set of eyes, to a place few of us will ever have dreamed of living.

At her first glimpse of the periphery of Al Aaiún, as they walk from the airport towards her new home, she is in awe seeing tents, bungalows, camels and herds of goats in the sand.

It was like walking into a fantasy, a whole new world.

The wind carried aloft the laughter of little girls playing a game. An indescribable vitality and joy can be found wherever humans exist. Even this barren and impoverished backwater was teeming with life, not a struggle for survival. For the residents of the desert, their births and deaths and everything in between were all part of a natural order. Looking out at the smoke ascending to the sky from their homes, I felt that these people were almost elegant in their serenity. Living carefree, in my understanding, is what a civilised spirit is all about.

The combination of her naivete, determination and feminism – her refusal to be stopped from doing what she wants – create some of the most hilarious and alarming moments. Her kindness and frankness gain her entry inside the culture and landscape, providing insights few are capable of accessing. People trusted her – yes they often took advantage of her – but she was a willing participant. They provided rich literary material, clearly!

The combination of her naivete, determination and feminism – her refusal to be stopped from doing what she wants – create some of the most hilarious and alarming moments. Her kindness and frankness gain her entry inside the culture and landscape, providing insights few are capable of accessing. People trusted her – yes they often took advantage of her – but she was a willing participant. They provided rich literary material, clearly!

This is one of those books I don’t wish to share much of what is inside, I prefer to say, “Read this, it’s so good!”

I was intrigued by the obsession she had to go and live in the Sahara, I was delighted that she lived at the wrong end of the street in among the permanent locals, I loved her sense of adventure, how she overcame boredom in searing heat, getting in the car and driving for hours in the desert. But it is her frankness, her empathy and sense of humour that make it an unforgettable read.

Reading Women in Translation

I picked this up to read for #WITMonth and it’s one of the best, that combination of travel to a new place, meeting local people through the perception of someone from a culture other than our own, priceless.

“Travel with an open heart, then bring back home the feelings that you find.” Sanmao

Further Reading

Colombia University: Interview with translator: Mike Fu

Words Without Borders, Essay by Jessica Chen (niece) March 2020: Sanmao’s Footprints: Remembering the Writer on Her 77th Birthday

New York Times Obituary: Overlooked No More: Sanmao, ‘Wandering Writer’ Who Found Her Voice in the Desert

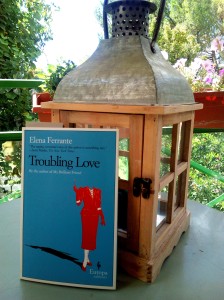

That’s Ferrante.

That’s Ferrante.

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

Evangalising Across the Argentinian Countryside

Evangalising Across the Argentinian Countryside

The opening sentence introduces us to the birth of a poverty-stricken community, one that will rise up despite numerous efforts to destroy it. As more displaced people hear of them, it continues to reassemble, grow, and become occupied by the marginalised, who do what they can to get ahead.

The opening sentence introduces us to the birth of a poverty-stricken community, one that will rise up despite numerous efforts to destroy it. As more displaced people hear of them, it continues to reassemble, grow, and become occupied by the marginalised, who do what they can to get ahead.

The more I read, the more this novel got its hooks into me. After a while, a pattern begins to emerge, one that is universal. To find a place where one can live authentically, and be at home.

The more I read, the more this novel got its hooks into me. After a while, a pattern begins to emerge, one that is universal. To find a place where one can live authentically, and be at home.

While her mother uses imagination to create a vision of what happened and where the missing are, Ruqayya’s advances then retreats, as the present awakens the past, rarely does she dwell in an idealised future.

While her mother uses imagination to create a vision of what happened and where the missing are, Ruqayya’s advances then retreats, as the present awakens the past, rarely does she dwell in an idealised future. There is no place that quite replaces the childhood environment and home, except perhaps to create one’s own family, and this Raqayya will do, with her son’s and the daughter, a girl Maryam her husband brings home one day from the hospital, adopting her as their own. And in growing things, not the almond tree or the olives, but flowers, a thing of beauty, the damask rose, the bird of paradise.

There is no place that quite replaces the childhood environment and home, except perhaps to create one’s own family, and this Raqayya will do, with her son’s and the daughter, a girl Maryam her husband brings home one day from the hospital, adopting her as their own. And in growing things, not the almond tree or the olives, but flowers, a thing of beauty, the damask rose, the bird of paradise. What a perfect way to navigate through 500 years of history of a country, without ever getting bogged down in the detail, to follow the lives of daughters, a matrilineal lineage, whose patterns are affected if not dictated by the context of the era within which they’ve lived.

What a perfect way to navigate through 500 years of history of a country, without ever getting bogged down in the detail, to follow the lives of daughters, a matrilineal lineage, whose patterns are affected if not dictated by the context of the era within which they’ve lived. I absolutely loved it, I read this because I seek out works by women in translation to read in August for #WITMonth and finding a book like this is such a joy, for it gives so much in its reading, great storytelling, a potted history of Brazil, a unique multiple women’s perspective and an introduction to an award winning author, the writer of ten novels, this her first translated into English.

I absolutely loved it, I read this because I seek out works by women in translation to read in August for #WITMonth and finding a book like this is such a joy, for it gives so much in its reading, great storytelling, a potted history of Brazil, a unique multiple women’s perspective and an introduction to an award winning author, the writer of ten novels, this her first translated into English. Celestial Bodies won the

Celestial Bodies won the  In yesterday’s post I mentioned I had just finished reading this book, a wonderful, if challenging work of translated fiction by the Iranian author Shokoofeh Azar, who lives in exile in Australia. This novel was shortlisted for the Stella Prize in 2018 (a literary award that celebrates Australian women’s writing and an organisation promoting cultural change).

In yesterday’s post I mentioned I had just finished reading this book, a wonderful, if challenging work of translated fiction by the Iranian author Shokoofeh Azar, who lives in exile in Australia. This novel was shortlisted for the Stella Prize in 2018 (a literary award that celebrates Australian women’s writing and an organisation promoting cultural change).

I have wanted to read this novel for a while, ever since reading

I have wanted to read this novel for a while, ever since reading