Though it was announced at the end of July I wasn’t paying attention during my busy summer, but before the short list is announced on September 14, I wanted to share the long list and short summaries of the titles, as this is often where we might find something that appeals.

The panel of judges this year includes historian Maya Jasanoff (Chair), writer and editor Horatia Harrod, actor Natascha McElhone, twice Booker-shortlisted novelist and professor Chigozie Obioma, and writer and former Archbishop Rowan Williams.

I haven’t read any of the titles but I do have a copy of Mary Lawson’s A Town Called Solace, which I thought looked like a light read that I might enjoy.

“Readers of every taste and every kind of interest will find something on this list. What we tried to do was hear what the books had to say to us. We find what marks all of these books is a really distinctive voice. Some of them are very lyrical, some of them are very spare, but there is a kind of deliberate quality and attention to the writing in each of these books that makes them really distinct and special.” Maya Jasanoff, Chair of Judges

Below are the 13 novels long listed.

A Passage North, Anuk Arudpragasam (Sri Lanka) (Granta Books)

A Passage North begins with a message from out of the blue: a telephone call informing Krishan that his grandmother’s caretaker, Rani, has died under unexpected circumstances. The news arrives soon after an email from Anjum, an impassioned yet aloof activist Krishnan fell in love with years before while living in Delhi, stirring old memories and desires from a world he left behind.

A Passage North begins with a message from out of the blue: a telephone call informing Krishan that his grandmother’s caretaker, Rani, has died under unexpected circumstances. The news arrives soon after an email from Anjum, an impassioned yet aloof activist Krishnan fell in love with years before while living in Delhi, stirring old memories and desires from a world he left behind.

As Krishan makes the long journey by train from Colombo into the war-torn Northern Province for Rani’s funeral, so begins an astonishing passage into the innermost reaches of a country. At once a powerful meditation on absence and longing, and an unsparing account of the legacy of Sri Lanka’s thirty-year civil war, this procession to a pyre ‘at the end of the earth’ lays bare the imprints of an island’s past, the unattainable distances between who we are and what we seek.

Written with precision and grace, Anuk Arudpragasam’s novel attempts to come to terms with life in the wake of devastation, a poignant memorial for those lost and those still alive.

Second Place, Rachel Cusk, (UK/Canada) (Faber)

A woman invites a famed artist to visit the remote coastal region where she lives, in the belief that his vision will penetrate the mystery of her life and landscape. Over the course of one hot summer, his provocative presence provides the frame for a study of female fate and male privilege, of the geometries of human relationships, and of the struggle to live morally between our internal and external worlds.

A woman invites a famed artist to visit the remote coastal region where she lives, in the belief that his vision will penetrate the mystery of her life and landscape. Over the course of one hot summer, his provocative presence provides the frame for a study of female fate and male privilege, of the geometries of human relationships, and of the struggle to live morally between our internal and external worlds.

With its examination of the possibility that art can both save and destroy us, Second Place attempts to affirm the human soul, while grappling with its darkest demons.

The Promise, Damon Galgut, (South Africa) (Chatto & Windus)

The Promise charts the crash and burn of a white South African family, living on a farm outside Pretoria. The Swarts are gathering for Ma’s funeral. The younger generation, Anton and Amor, detest everything the family stand for, not least the failed promise to the Black woman who has worked for them her whole life. After years of service, Salome was promised her own house, her own land… yet somehow, as each decade passes, that promise remains unfulfilled.

The Promise charts the crash and burn of a white South African family, living on a farm outside Pretoria. The Swarts are gathering for Ma’s funeral. The younger generation, Anton and Amor, detest everything the family stand for, not least the failed promise to the Black woman who has worked for them her whole life. After years of service, Salome was promised her own house, her own land… yet somehow, as each decade passes, that promise remains unfulfilled.

The narrator’s eye shifts and blinks: moving fluidly between characters, flying into their dreams; deliciously lethal in its observation. And as the country moves from old deep divisions to its new so-called fairer society, the lost promise of more than just one family hovers behind the novel’s title.

In this story of a diminished family, sharp and tender emotional truths hit home.

The Sweetness of Water, Nathan Harris (US) (Tinder Press)

In the dying days of the American Civil War, newly freed brothers Landry and Prentiss find themselves cast into the world without a penny to their names. Forced to hide out in the woods near their former Georgia plantation, they’re soon discovered by the land’s owner, George Walker, a man still reeling from the loss of his son in the war.

In the dying days of the American Civil War, newly freed brothers Landry and Prentiss find themselves cast into the world without a penny to their names. Forced to hide out in the woods near their former Georgia plantation, they’re soon discovered by the land’s owner, George Walker, a man still reeling from the loss of his son in the war.

When the brothers begin to live and work on George’s farm, tentative bonds of trust and union begin to blossom between the strangers. But this sanctuary survives on a knife’s edge, and it isn’t long before the inhabitants of the nearby town of Old Ox react with fury at alliances being formed a few miles away.

Conjuring a world fraught with tragedy and violence yet threaded through with hope, The Sweetness of Water is a debut novel unique in its power to move and enthrall. An Oprah pick for her July book club and on Barack Obama’s summer reading list.

Klara and the Sun, Kazuo Ishiguro (UK) (Faber)

From her place in the store, Klara, an Artificial Friend with outstanding observational qualities, watches carefully the behaviour of those who come in to browse, and those who pass in the street outside. She remains hopeful that a customer will soon choose her, but when the possibility emerges that her circumstances may change for ever, Klara is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans.

From her place in the store, Klara, an Artificial Friend with outstanding observational qualities, watches carefully the behaviour of those who come in to browse, and those who pass in the street outside. She remains hopeful that a customer will soon choose her, but when the possibility emerges that her circumstances may change for ever, Klara is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans.

In Klara and the Sun, Kazuo Ishiguro looks at our rapidly-changing modern world through the eyes of an unforgettable narrator to explore a fundamental question: what does it mean to love? Also on Barack Obama’s summer reading list.

An Island, Karen Jennings (South Africa) (Holland House Books)

Samuel has lived alone for a long time; one morning he finds the sea has brought someone to offer companionship and to threaten his solitude…

Samuel has lived alone for a long time; one morning he finds the sea has brought someone to offer companionship and to threaten his solitude…

A young refugee washes up unconscious on the beach of a small island inhabited by no one but Samuel, an old lighthouse keeper. Unsettled, Samuel is soon swept up in memories of his former life on the mainland: a life that saw his country suffer under colonisers, then fight for independence, only to fall under the rule of a cruel dictator; and he recalls his own part in its history. In this new man’s presence he begins to consider, as he did in his youth, what is meant by land and to whom it should belong. To what lengths will a person go in order to ensure that what is theirs will not be taken from them?

A novel about guilt and fear, friendship and rejection; about the meaning of home.

A Town Called Solace, Mary Lawson (Canada) (Chatto & Windus)

Clara’s sister is missing. Angry, rebellious Rose had a row with their mother, stormed out of the house and simply disappeared. Eight-year-old Clara, isolated by her distraught parents’ efforts to protect her from the truth, is grief-stricken and bewildered. Liam Kane, newly divorced, newly unemployed, newly arrived in this small northern town, moves into the house next door – a house left to him by an old woman he can barely remember — and within hours gets a visit from the police. It seems he’s suspected of a crime.

Clara’s sister is missing. Angry, rebellious Rose had a row with their mother, stormed out of the house and simply disappeared. Eight-year-old Clara, isolated by her distraught parents’ efforts to protect her from the truth, is grief-stricken and bewildered. Liam Kane, newly divorced, newly unemployed, newly arrived in this small northern town, moves into the house next door – a house left to him by an old woman he can barely remember — and within hours gets a visit from the police. It seems he’s suspected of a crime.

At the end of her life Elizabeth Orchard is thinking about a crime too, one committed thirty years ago that had tragic consequences for two families and in particular for one small child. She desperately wants to make amends before she dies. Set in Northern Ontario in 1972, A Town Called Solace explores the relationships of these three people brought together by fate and the mistakes of the past. By turns gripping and darkly funny, it uncovers the layers of grief and remorse and love that connect us, but shows that sometimes a new life is possible.

No One is Talking About This, Patricia Lockwood (US) (Bloomsbury Circus)

A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to adoring fans, her entire existence overwhelmed by the internet — or what she terms ‘the portal’. Are we in hell? the people of the portal ask themselves. Who are we serving? Are we all just going to keep doing this until we die?

A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to adoring fans, her entire existence overwhelmed by the internet — or what she terms ‘the portal’. Are we in hell? the people of the portal ask themselves. Who are we serving? Are we all just going to keep doing this until we die?

Two texts from her mother pierce the fray: ‘Something has gone wrong,’ and ‘How soon can you get here?’ As real life and its stakes collide with the increasing absurdity of the portal, the woman confronts a world that seems to contain both an abundance of proof that there is goodness, empathy and justice in the universe, and a deluge of evidence to the contrary.

Sincere and profane, No One Is Talking About This is a love letter to the infinite scroll, a meditation on love, language and human connection from an original voice of our time.

The Fortune Men, Nadifa Mohamed (Somalia/UK) (Viking, Penguin)

Mahmood Mattan is a fixture in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay, 1952, which bustles with Somali and West Indian sailors, Maltese businessmen and Jewish families. A father, a chancer, a some-time petty thief, he is many things but not a murderer.

Mahmood Mattan is a fixture in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay, 1952, which bustles with Somali and West Indian sailors, Maltese businessmen and Jewish families. A father, a chancer, a some-time petty thief, he is many things but not a murderer.

So when a shopkeeper is brutally killed and all eyes fall on him, Mahmood isn’t too worried. It is true that he has been getting into trouble more often since his Welsh wife Laura left him. But Mahmood is secure in his innocence in a country where he thinks justice is served.

It is only in the run-up to the trial, as the prospect of freedom dwindles, that it will dawn on Mahmood that he is in a terrifying fight for his life — against conspiracy, prejudice and the inhumanity of the state. Under the shadow of the hangman’s noose, he begins to realise that the truth may not be enough to save him.

Bewilderment, Richard Powers (US) (Hutchinson Heinemann)

Theo Byrne is a promising young astrobiologist who has found a way to search for life on other planets dozens of light years away. The widowed father of an unusual nine-year-old, his son Robin is funny, loving and filled with plans. He thinks and feels deeply, adores animals and spends hours painting elaborate pictures. On the verge of being expelled from third grade for smashing his friend’s face with a metal thermos, this rare and troubled boy is being recommended psychoactive drugs.

Theo Byrne is a promising young astrobiologist who has found a way to search for life on other planets dozens of light years away. The widowed father of an unusual nine-year-old, his son Robin is funny, loving and filled with plans. He thinks and feels deeply, adores animals and spends hours painting elaborate pictures. On the verge of being expelled from third grade for smashing his friend’s face with a metal thermos, this rare and troubled boy is being recommended psychoactive drugs.

What can a father do or say when his son wants an explanation for a world that is clearly in love with its own destruction? The only thing for it is to take the boy to other planets, all the while fostering his desperate campaign to help save this one.

China Room, Sunjeev Sahota (UK) (Harvill Secker)

Mehar, a young bride in rural 1929 Punjab, is trying to discover the identity of her new husband. She and her sisters-in-law, married to three brothers in a single ceremony, spend their days hard at work in the family’s ‘china room’, sequestered from contact with the men.

Mehar, a young bride in rural 1929 Punjab, is trying to discover the identity of her new husband. She and her sisters-in-law, married to three brothers in a single ceremony, spend their days hard at work in the family’s ‘china room’, sequestered from contact with the men.

When Mehar develops a theory as to which of them is hers, a passion is ignited that will put more than one life at risk. Spiralling around Mehar’s story is that of a young man who in 1999 travels from England to the now-deserted farm, its ‘china room’ locked and barred. In enforced flight from the traumas of his adolescence — his experiences of addiction, racism, and estrangement from the culture of his birth — he spends a summer in painful contemplation and recovery, finally finding the strength to return home. Partly inspired by the author’s family history it explores how systems of power affect individual lives and the human capacity to resist them.

Great Circle, Maggie Shipstead (US)(Doubleday)

In 1920s Montana, wild-hearted orphan Marian Graves spends her days roaming the rugged forests and mountains of her home. When she witnesses the roll, loop and dive of two barnstorming pilots, she promises herself that one day she too will take to the skies.

In 1920s Montana, wild-hearted orphan Marian Graves spends her days roaming the rugged forests and mountains of her home. When she witnesses the roll, loop and dive of two barnstorming pilots, she promises herself that one day she too will take to the skies.

Years later, after a series of reckless romances and a spell flying to aid the British war effort, Marian embarks on a treacherous flight around the globe in search of the freedom she craves, never to be seen again.

More than half a century later, Hadley Baxter, a troubled Hollywood starlet beset by scandal, is drawn to play Marian Graves in her biopic, a role that leads her to probe the deepest mysteries of the vanished pilot’s life.

Light Perpetual, Francis Spufford (UK)(Faber)

Lunchtime on a Saturday, 1944: the Woolworths on Bexford High Street in South London receives a delivery of aluminum saucepans. A crowd gathers to see the first new metal in ages—after all, everything’s been melted down for the war effort. An instant later, the crowd is gone; incinerated. Among the shoppers were five young children.

Lunchtime on a Saturday, 1944: the Woolworths on Bexford High Street in South London receives a delivery of aluminum saucepans. A crowd gathers to see the first new metal in ages—after all, everything’s been melted down for the war effort. An instant later, the crowd is gone; incinerated. Among the shoppers were five young children.

Who were they? What futures did they lose? Inspired by real events, written in luminous prose, the author reimagines the lives of five souls as they pass through the extraordinary changes of the twentieth-century London.

* * * * *

That’s it, the 13 books that make up the Booker’s dozen, chosen from 158 submissions. Are there any that jump out at you, that look interesting?

I’m intrigued by Sri Lankan author Anuk Arudpragasam’s novel, I’m always going to be more interested in stories that are set within another culture and I recall wishing to read his first novel, though I never did. Bewilderment seems to be receiving unanimously high praise by those who’ve had the chance to an early copy, but I really have no idea what will make the short list, watch this space to find out!

“Many of them consider how people grapple with the past—whether personal experiences of grief or dislocation or the historical legacies of enslavement, apartheid, and civil war. Many examine intimate relationships placed under stress, and through them meditate on ideas of freedom and obligation, or on what makes us human.”

Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris (Yugoslav/Cornish – UK) (Historical Fiction)

Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris (Yugoslav/Cornish – UK) (Historical Fiction) Pod by Laline Paull (UK) (Nature/Oceanic Fantasy)

Pod by Laline Paull (UK) (Nature/Oceanic Fantasy) Fire Rush by Jacqueline Crooks (Jamaican/British) (Historical Fiction)

Fire Rush by Jacqueline Crooks (Jamaican/British) (Historical Fiction)  Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Northern Ireland) (Contemporary Fiction)

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy (Northern Ireland) (Contemporary Fiction) The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell (UK/Ireland) (Historical Fiction)

The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell (UK/Ireland) (Historical Fiction) Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (US) (Fan Fiction)

Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver (US) (Fan Fiction) A Passage North begins with a message from out of the blue: a telephone call informing Krishan that his grandmother’s caretaker, Rani, has died under unexpected circumstances. The news arrives soon after an email from Anjum, an impassioned yet aloof activist Krishnan fell in love with years before while living in Delhi, stirring old memories and desires from a world he left behind.

A Passage North begins with a message from out of the blue: a telephone call informing Krishan that his grandmother’s caretaker, Rani, has died under unexpected circumstances. The news arrives soon after an email from Anjum, an impassioned yet aloof activist Krishnan fell in love with years before while living in Delhi, stirring old memories and desires from a world he left behind. A woman invites a famed artist to visit the remote coastal region where she lives, in the belief that his vision will penetrate the mystery of her life and landscape. Over the course of one hot summer, his provocative presence provides the frame for a study of female fate and male privilege, of the geometries of human relationships, and of the struggle to live morally between our internal and external worlds.

A woman invites a famed artist to visit the remote coastal region where she lives, in the belief that his vision will penetrate the mystery of her life and landscape. Over the course of one hot summer, his provocative presence provides the frame for a study of female fate and male privilege, of the geometries of human relationships, and of the struggle to live morally between our internal and external worlds. The Promise charts the crash and burn of a white South African family, living on a farm outside Pretoria. The Swarts are gathering for Ma’s funeral. The younger generation, Anton and Amor, detest everything the family stand for, not least the failed promise to the Black woman who has worked for them her whole life. After years of service, Salome was promised her own house, her own land… yet somehow, as each decade passes, that promise remains unfulfilled.

The Promise charts the crash and burn of a white South African family, living on a farm outside Pretoria. The Swarts are gathering for Ma’s funeral. The younger generation, Anton and Amor, detest everything the family stand for, not least the failed promise to the Black woman who has worked for them her whole life. After years of service, Salome was promised her own house, her own land… yet somehow, as each decade passes, that promise remains unfulfilled. In the dying days of the American Civil War, newly freed brothers Landry and Prentiss find themselves cast into the world without a penny to their names. Forced to hide out in the woods near their former Georgia plantation, they’re soon discovered by the land’s owner, George Walker, a man still reeling from the loss of his son in the war.

In the dying days of the American Civil War, newly freed brothers Landry and Prentiss find themselves cast into the world without a penny to their names. Forced to hide out in the woods near their former Georgia plantation, they’re soon discovered by the land’s owner, George Walker, a man still reeling from the loss of his son in the war. From her place in the store, Klara, an Artificial Friend with outstanding observational qualities, watches carefully the behaviour of those who come in to browse, and those who pass in the street outside. She remains hopeful that a customer will soon choose her, but when the possibility emerges that her circumstances may change for ever, Klara is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans.

From her place in the store, Klara, an Artificial Friend with outstanding observational qualities, watches carefully the behaviour of those who come in to browse, and those who pass in the street outside. She remains hopeful that a customer will soon choose her, but when the possibility emerges that her circumstances may change for ever, Klara is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. Samuel has lived alone for a long time; one morning he finds the sea has brought someone to offer companionship and to threaten his solitude…

Samuel has lived alone for a long time; one morning he finds the sea has brought someone to offer companionship and to threaten his solitude… Clara’s sister is missing. Angry, rebellious Rose had a row with their mother, stormed out of the house and simply disappeared. Eight-year-old Clara, isolated by her distraught parents’ efforts to protect her from the truth, is grief-stricken and bewildered. Liam Kane, newly divorced, newly unemployed, newly arrived in this small northern town, moves into the house next door – a house left to him by an old woman he can barely remember — and within hours gets a visit from the police. It seems he’s suspected of a crime.

Clara’s sister is missing. Angry, rebellious Rose had a row with their mother, stormed out of the house and simply disappeared. Eight-year-old Clara, isolated by her distraught parents’ efforts to protect her from the truth, is grief-stricken and bewildered. Liam Kane, newly divorced, newly unemployed, newly arrived in this small northern town, moves into the house next door – a house left to him by an old woman he can barely remember — and within hours gets a visit from the police. It seems he’s suspected of a crime. A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to adoring fans, her entire existence overwhelmed by the internet — or what she terms ‘the portal’. Are we in hell? the people of the portal ask themselves. Who are we serving? Are we all just going to keep doing this until we die?

A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to adoring fans, her entire existence overwhelmed by the internet — or what she terms ‘the portal’. Are we in hell? the people of the portal ask themselves. Who are we serving? Are we all just going to keep doing this until we die? Mahmood Mattan is a fixture in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay, 1952, which bustles with Somali and West Indian sailors, Maltese businessmen and Jewish families. A father, a chancer, a some-time petty thief, he is many things but not a murderer.

Mahmood Mattan is a fixture in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay, 1952, which bustles with Somali and West Indian sailors, Maltese businessmen and Jewish families. A father, a chancer, a some-time petty thief, he is many things but not a murderer. Theo Byrne is a promising young astrobiologist who has found a way to search for life on other planets dozens of light years away. The widowed father of an unusual nine-year-old, his son Robin is funny, loving and filled with plans. He thinks and feels deeply, adores animals and spends hours painting elaborate pictures. On the verge of being expelled from third grade for smashing his friend’s face with a metal thermos, this rare and troubled boy is being recommended psychoactive drugs.

Theo Byrne is a promising young astrobiologist who has found a way to search for life on other planets dozens of light years away. The widowed father of an unusual nine-year-old, his son Robin is funny, loving and filled with plans. He thinks and feels deeply, adores animals and spends hours painting elaborate pictures. On the verge of being expelled from third grade for smashing his friend’s face with a metal thermos, this rare and troubled boy is being recommended psychoactive drugs. Mehar, a young bride in rural 1929 Punjab, is trying to discover the identity of her new husband. She and her sisters-in-law, married to three brothers in a single ceremony, spend their days hard at work in the family’s ‘china room’, sequestered from contact with the men.

Mehar, a young bride in rural 1929 Punjab, is trying to discover the identity of her new husband. She and her sisters-in-law, married to three brothers in a single ceremony, spend their days hard at work in the family’s ‘china room’, sequestered from contact with the men. In 1920s Montana, wild-hearted orphan Marian Graves spends her days roaming the rugged forests and mountains of her home. When she witnesses the roll, loop and dive of two barnstorming pilots, she promises herself that one day she too will take to the skies.

In 1920s Montana, wild-hearted orphan Marian Graves spends her days roaming the rugged forests and mountains of her home. When she witnesses the roll, loop and dive of two barnstorming pilots, she promises herself that one day she too will take to the skies. Lunchtime on a Saturday, 1944: the Woolworths on Bexford High Street in South London receives a delivery of aluminum saucepans. A crowd gathers to see the first new metal in ages—after all, everything’s been melted down for the war effort. An instant later, the crowd is gone; incinerated. Among the shoppers were five young children.

Lunchtime on a Saturday, 1944: the Woolworths on Bexford High Street in South London receives a delivery of aluminum saucepans. A crowd gathers to see the first new metal in ages—after all, everything’s been melted down for the war effort. An instant later, the crowd is gone; incinerated. Among the shoppers were five young children.

These and other questions lead her to re-examine the past, present and future, captured here in The Chalice and the Blade, looking at human history and pre-history and at both male and female aspects of humanity and in particular, those societies where the feminine aspect was revered.

These and other questions lead her to re-examine the past, present and future, captured here in The Chalice and the Blade, looking at human history and pre-history and at both male and female aspects of humanity and in particular, those societies where the feminine aspect was revered.

Though this was written 30 years ago, there is a sequel due to be published in August 2019, in collaboration with peace anthropologist Douglas P. Fry

Though this was written 30 years ago, there is a sequel due to be published in August 2019, in collaboration with peace anthropologist Douglas P. Fry

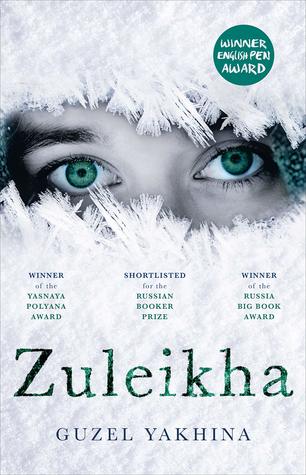

Last year my favourite read

Last year my favourite read

Guzel Yakhina’s grandmother was arrested in the 1930’s, taken by horseback to Kazan and then on a long railway journey (over 2,000 miles) to Siberia. She was exiled from the age of 7 until 17 years, returning to her native village in 1947. It was these formative childhood years that were in a large part responsible for her formidable character.

Guzel Yakhina’s grandmother was arrested in the 1930’s, taken by horseback to Kazan and then on a long railway journey (over 2,000 miles) to Siberia. She was exiled from the age of 7 until 17 years, returning to her native village in 1947. It was these formative childhood years that were in a large part responsible for her formidable character. Although I’ve read reviews and seen this book appear often over the last year, and knew I really wanted to read it, I couldn’t remember what is was about or why.

Although I’ve read reviews and seen this book appear often over the last year, and knew I really wanted to read it, I couldn’t remember what is was about or why. The British translation (by Jessica Moore) is entitled Mend the Living, broader in scope, it references the many who lie with compromised organs, who dwell in a twilight zone of half-lived lives, waiting to see if their match will come up, knowing when it does, it will likely be a sudden opportunity, to receive a healthy heart, liver, or kidney from a donor, taken violently from life.

The British translation (by Jessica Moore) is entitled Mend the Living, broader in scope, it references the many who lie with compromised organs, who dwell in a twilight zone of half-lived lives, waiting to see if their match will come up, knowing when it does, it will likely be a sudden opportunity, to receive a healthy heart, liver, or kidney from a donor, taken violently from life. The translator Jessica Moore refers to her task in translating the authors work, as ‘grappling with Maylis’s labyrinthe phrases’, which can feel like what it must be like to be an amateur surfer facing the wave, trying and trying again, to find the one that fits, the wave and the rider, the words and the translator. She gives up trying to turn what the author meant into suitable phrases and leaves interpretation to the future, potential reader, us.

The translator Jessica Moore refers to her task in translating the authors work, as ‘grappling with Maylis’s labyrinthe phrases’, which can feel like what it must be like to be an amateur surfer facing the wave, trying and trying again, to find the one that fits, the wave and the rider, the words and the translator. She gives up trying to turn what the author meant into suitable phrases and leaves interpretation to the future, potential reader, us.