In 2020 I read more books than usual, as a result of the diminished social and leisure life we’ve all had to rein in. That extra home time I gifted to my reading and writing activities and was aptly rewarded.

Books That Soothe the Soul

It was a slow start as the year began, still in the terrible lull that followed the death of my teenage daughter in August 2019. I couldn’t read and when I tried it wasn’t easy to find the right match. The few books that soothed me were more of a spiritual nature, Julie Ryan’s Angelic Attendants Felicity Warner’s Sacred Oils, and The Grief Recovery Handbook; though I wasn’t able to express here how they sustained me, they just did.

Confinement in France

Then in March we were ordered to stay home. In France, it is known as le confinement. For two months I wasn’t able to work and we were only allowed to leave home for an hour a day for exercise within a 1 kilometre radius of home and to carry a printed attestation each time we left home. Ironically, while this was the beginning of a difficult period for many, it was the beginning of a return to a new reality and routine for me. The daily walk, the immense gratitude, the arrival of spring, noticed and appreciated in a new way. I was finding a way back to balance, re-centering.

I wrote a series of blog posts entitled Reading Lists for Total Confinement, which included my:

Top Five Spiritual Well Being Reads, Top Five Nature Inspired Reads, Top Five Uplifting Reads,

Top Five Spiritual Well Being Reads, Top Five Nature Inspired Reads, Top Five Uplifting Reads,

Top Five Translated Fiction, Top Five Memoirs and the Top Five books I was intending to read next.

It was a tipping point and re-entry back into reading, and one title that I slow-read and drip-fed myself, no more than a chapter a day, during those two months, that was like an uplifting, therapeutic intervention was Cuban-American Alberto Villoldo’s Courageous Dreaming.

Our situation may be a difficult one, but it’s only a nightmare if we choose to make that our reality. By taking the facts and writing a new story with them, we can script a different experience of reality.

He reminds us that we are all living within our own stories, that they can either stay stuck in the past and put on repeat, or we can rewrite them and courageously imagine or dream a better version of ourselves and of our future. Never was there a better time to refresh this knowledge and to recall the benefit of expressing one’s creativity.

“Curing is the elimination of symptoms. Healing is a journey on which you discover the cause of your ailment and make fundamental life changes from diet to belief systems that will create health.”

Travelling the World From Home

And so my reading mojo returned and from the comfort of home, I rested in the present, resisted the pull of other media and travelled the world through literature, reading a little over a book a week, by authors from 34 countries, a third of them in translation.

Continuing to favour the imagination in storytelling, 70% of the books I read were fiction, however I read more non-fiction this year than ever and some of my favourite reads came from this genre.

Here are my Top Fiction and Non-Fiction Reads, as well as my annual ‘One Outstanding Read of the Year’.

Outstanding Read of the Year

A Ghost in the Throat, Doireann Ní Ghríofa (Ireland) – I read so many deserving, excellent works of fiction that were also outstanding, so I revisited this book to remind me why it deserves to be elevated above the rest.

A Ghost in the Throat, Doireann Ní Ghríofa (Ireland) – I read so many deserving, excellent works of fiction that were also outstanding, so I revisited this book to remind me why it deserves to be elevated above the rest.

It may be due to my own journey, perhaps there is something about this book that validates my desire to write something fragmented and unconventional, something that isn’t easily categorised.

This work of creative nonfiction is as personal as it is universal, it uses a poem and the author’s passion for it, to bring together various threads of her own life, both before having a family, while on the threshold of birth, being in proximity to death, experiencing love and daring to author a work that bursts beyond genre, challenges academia and waves the flag for women in all her multifaceted complexity. Language, poetry, babies, dark nights of the soul, creativity, writing, Irish life, the burying and rise of women authors working in partnership.

Much of this book was written sitting inside her car, parked up after dropping her children at school. Forget excuses about finding time to write, or a room of one’s own, Ni Ghriofa deserves a prize for perseverance, achievement, breaking all convention and writing an utterly engaging 21st century kick-ass, feminist oeuvre. Just brilliant. Read it people!

Top Fiction Reads of 2020

Here, in no particular order is the best of the fiction I read in 2020, reading experiences that have stayed with me, that I continue to highly recommend to you all, just click on a title to read my original review:

Fresh Water for Flowers, Valérie Perrin (France) tr. Hildegarde Serle – this was the last book I read in 2020 and a fitting way to end the year, it is a beautiful translation of what was a bestseller in France in 2018, about a young woman who becomes a train level-crossing keeper, then cemetery-keeper. It a story of love, loss and redemption told through an extensive cast of characters, both living and not, demonstrating the interconnectivity of lives, viewed through a compassionate lens. Evocative, lyrical, character lead and quintessentially French.

The Book of Harlan, Bernice McFadden (US) – this work of historical fiction, in part inspired by the author’s own family was hugely memorable and one of the first in 2020 that really stood out for me. It was also the book that lead me into a bit of Harlem Renaissance period of reading which uncovered some excellent older reads that I adored. It follows the life of Harlan from his early years with his grandparents to Harlem and the music scene, to Paris and Germany, and while reading I was accompanied by the music of that era which McFadden incorporates brilliantly into the narrative and had me pausing, listening, watching and learning all the way through. Absolutely brilliant.

Quicksand, Nella Larsen (US) (semi-autobiographical) – while the reading world in 2020 was devouring Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half, a contemporary exploration of the American history of passing, I opted to read Nella Larsen’s classic novellas Passing (1929) and Quicksand (1928). I enjoyed Passing, however the semi-autobiographical Quicksand was equally brilliant. It follows the life of a young woman, a third culture kid of mixed race parentage with a white mother from Denmark and a black father from the Danish West Indies (as were Nella’s parents), foreigners, immigrants, a child growing up with little connection to either culture, who has trouble settling in to the society she is born into. Brilliantly written and observed, I highly recommend it.

Crossing the Mangrove, Maryse Condé (Guadeloupe) tr. Richard Philcox (French) – I love reading Condé and managed another two this year including I, Tituba Black Witch of Salem however Crossing the Mangrove was a stand out and had me shaking my head in admiration of her talent. Here she returns to a Caribbean setting, where the death and subsequent funeral of an outsider brings together a number of characters, each of whom narrate a chapter, revealing the multilayered diversity of island society. Though the man’s death is a mystery, it is is more of a ‘noir‘ novel, no tidy resolution, rather an insightful, penetrative look at the folly of life. Brilliant, one I want to reread.

Circe, Madeline Miller (US) – I’d wanted to read this for a while and finally did so earlier in the year and loved it. With Circe, Miller brings a refreshing, feminist perspective to an ancient Greek myth, that reconsiders the motivations of the jealous nymph, allowing her to evolve and grow into the fully fledged, capable, learned, wise woman self that she becomes while living in exile. Rather than the evil sorceress men have historically depicted her as, here we meet a more nuanced, balanced and complex character. Brilliant.

The Adventures of China Iron, Gabriela Cabezón Cámara (Argentina), tr. Fiona Mackintosh, Iona Macintyre (Spanish) – short listed for the International Booker Prize 2020 this was one of the most humorous books I’ve read in a while, a contemporary retelling of a well-known Argentinian gaucho poem Martin Fierro by José Hernández; that title a lament for a disappearing way of life, whereas this is an elegy to what could have been, told from the perspective of his little mentioned wife, a tale of adventure, emancipation, sexual freedom and liberation. It didn’t win, but it remains a firm favourite of the year for me.

A Girl Returned, Donatella Di Pietrantonio (Italy), tr. Ann Goldstein – this novella was an unexpected surprise, I read four books translated from Italian this year, Elena Ferrante’s latest The Lying Life of Adults and her debut Troubling Love, both of which were excellent, but it was this novella that has stayed in my mind. A thirteen year old girl is returned to the family she was born to without being told why. Determined to unravel the cause of abandonment by both sets of parents, at birth by her biological family and now by her adoptive family, the book explores the changes that happen as she detaches from one and becomes entwined in the other. It’s brilliantly depicted, thought provoking and insightful.

Auē, Becky Manawatu (NZ) – last year I read the winner of the NZ Book Award This Mortal Boy by Fiona Kidman and this year when Auē took the prize, I bought a copy immediately. Very different books, both explore a darker aspect of New Zealand life. Aue has you on the edge of the seat, following the lives of an eight year old boy, his older brother and a couple they are connected to. The characters are unforgettable, portrayed with empathy without indulging sentimentality. The proximity of vulnerability to brutality is intense and unforgettable. You won’t read anything else like this in 2020. Extraordinary literary fiction from elsewhere. Go on. Read it.

Top Non-Fiction Reads of 2020

Stories of the Sahara, Sanmao (Taiwan) tr. Mike Fu (Chinese) – incredible that it has taken 40 years for this title to come to our attention and be translated. This was definitely the funniest, sometimes scariest and surprising read of the year. Sanmao wasn’t exactly a hippy, she was one of a kind, a woman way ahead of her time and outside of her culture, travelling with her Spanish boyfriend in the 70’s with the intention to live in the Spanish Sahara like a local, thanks to a deep passion for the landscape and curiosity for its people. The situations she finds herself in, the people she meets and the tender love affair with the man who indulges her whims, was a close runner up for outstanding read of the year.

Atlantis, A Journey in Search of Beauty, Carlo & Renzo Piano (Italy), tr. Will Schutt – another from Italy, this is a father and son adventure, a journalist and an architect who take an eight month trip by boat around the world, visiting the various sites of Renzo Piano’s architectural constructions. I requested it on a whim and found it both educational, entertaining, philosophical and surprisingly riveting. This now 80 year old father is an inspiration and his son an engaging, provocative narrator. It left me wishing that more familial partnerships could come together to capture these kind of conversations, that have such universal appeal.

Handiwork, Sara Baume (Ireland) – an author whose name I was familiar with, I read Handiwork after finding it was published by Tramp Press, who published A Ghost in the Throat. I couldn’t believe my luck to have come across another title that blurs the boundaries of genre. Handiwork is an artwork, a lyrical account of a year spent sculpting and painting small birds for an installation. Her morning she spends writing, her afternoons making stuff with her hands, just her Dad and Grandad did before her. An eclectic collage of thoughts, observations, memories and quotes from various masters, it was a total pleasure to read.

A Spell in the Wild, A Year & Six Centuries of Magic, Alice Tarbuck (Scotland) – after reading two novels about Tituba, the black slave woman accused of witchcraft, I decided to read a book with a contemporary view of witchcraft, now that we are safely beyond the era when admitting to being partial to the practice of ritual outside of acceptable religion could get you hanged. And I stumbled across the incredibly knowledgeable author Dr Alice Tarbuck, who puts the formality of her PhD aside to share her monthly rituals, spells and historical anecdotes from a vast canon of literature that portrayed women as something wicked and powerful that needed to be suppressed if not put down. Her six centuries of magic is quite the opposite, unputdownable.

The Warmth of Other Suns, Irene Wilkerson (US) – the product of years of research, and an intimate relationship with three people, from three different states and decades through whom Wilkerson recounts history, this is a factual account of the little acknowledged great migration of African Americans out of the Jim Crow Southern states of America, beginning just after WW1 in 1915, continuing until the 1970’s. It’s a long continuous diaspora that had a significant impact on families, their culture and connections between their new home and old and a fascinating insight into black American history told in a compelling way.

* * * * * * *

And there it is, a summary of the most memorable books I read in 2020, thank you for your patience if you managed to read this far! Do you have a few absolute favourite reads of the year to share? Did you read any of those I mention here? Let me know in the comments below.

Having left Haiti when she was twelve years to live in America, it’s not surprising that her stories involve a cast of characters with connections to her home country and a neighbourhood in Miami Dade County, Florida referred to as ‘Little Haiti’ after a Haitian pro-democracy activist wrote to a Miami newspaper referring to his new home as “Little Port-au-Prince” which was shortened and known thereafter as ‘Little Haiti’.

Having left Haiti when she was twelve years to live in America, it’s not surprising that her stories involve a cast of characters with connections to her home country and a neighbourhood in Miami Dade County, Florida referred to as ‘Little Haiti’ after a Haitian pro-democracy activist wrote to a Miami newspaper referring to his new home as “Little Port-au-Prince” which was shortened and known thereafter as ‘Little Haiti’.

What a refreshing read to end 2020 with, a novel of interwoven characters and connections, threaded throughout the life of Violette Touissant, given up at birth.

What a refreshing read to end 2020 with, a novel of interwoven characters and connections, threaded throughout the life of Violette Touissant, given up at birth.

Every summer she stays in the chalet of her friend Célia, in the calanque of Sormiou, Marseille. A place of refuge and rejevenation, that Perrin too brings alive, eliciting the recovery and rehabilitation this nature-protected part of the Mediterranean offers humanity.

Every summer she stays in the chalet of her friend Célia, in the calanque of Sormiou, Marseille. A place of refuge and rejevenation, that Perrin too brings alive, eliciting the recovery and rehabilitation this nature-protected part of the Mediterranean offers humanity. Though we learn that Vivek is dead from the cover and in the opening pages, the novel is in a sense a mystery as the details around the death are not revealed until the end. The novel is set in Nigeria, in a community of mostly mixed race families.

Though we learn that Vivek is dead from the cover and in the opening pages, the novel is in a sense a mystery as the details around the death are not revealed until the end. The novel is set in Nigeria, in a community of mostly mixed race families.

I admit I found it difficult to believe that a young woman could convince the tough crew of one of the last fishing boats to accept her suggestion to follow the blinking light of a few birds, over the knowledge and intentions of an experienced captain.

I admit I found it difficult to believe that a young woman could convince the tough crew of one of the last fishing boats to accept her suggestion to follow the blinking light of a few birds, over the knowledge and intentions of an experienced captain. While every adoptee’s experience is different, there are so many aspects to the experience and responses to them that resonate with other adoptees, that reading a memoir like this can be very helpful, sharing experiences helps us understand.

While every adoptee’s experience is different, there are so many aspects to the experience and responses to them that resonate with other adoptees, that reading a memoir like this can be very helpful, sharing experiences helps us understand.

It is a very personal account and kudos to the author for having the courage to share it and inviting readers to go along on the emotional roller coaster of a journey it must have been.

It is a very personal account and kudos to the author for having the courage to share it and inviting readers to go along on the emotional roller coaster of a journey it must have been. I came across this book in a newsletter I read by the founders of Tramp Press, who published two nonfiction books I recently read and loved, Doireann Ni Ghriofa’s

I came across this book in a newsletter I read by the founders of Tramp Press, who published two nonfiction books I recently read and loved, Doireann Ni Ghriofa’s

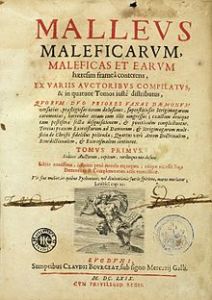

Tituba existed, she was accused and ultimately set free, however, despite the shelves of history books about the Salem witch trials, there is little factual information about her, who she was, who freed her, or her life after release from prison.

Tituba existed, she was accused and ultimately set free, however, despite the shelves of history books about the Salem witch trials, there is little factual information about her, who she was, who freed her, or her life after release from prison. And so Tituba is given a past, skills and knowledge and might have remained in that life, had she not grown into a young woman with desires herself and fallen for the man who would become her husband John Indian.

And so Tituba is given a past, skills and knowledge and might have remained in that life, had she not grown into a young woman with desires herself and fallen for the man who would become her husband John Indian.

Seven titles were shortlisted for the annual Women in Translation award from 132 eligible entries, 16 titles made the initial longlist:

Seven titles were shortlisted for the annual Women in Translation award from 132 eligible entries, 16 titles made the initial longlist: Abigail by Magda Szabó (Hungary), translated by Len Rix (MacLehose Press, 2020)

Abigail by Magda Szabó (Hungary), translated by Len Rix (MacLehose Press, 2020) Happiness, As Such by Natalia Ginzburg (Italy) translated by Minna Zallmann Proctor (Daunt Books Publishing, 2019)

Happiness, As Such by Natalia Ginzburg (Italy) translated by Minna Zallmann Proctor (Daunt Books Publishing, 2019) Lake Like a Mirror by Ho Sok Fong (Malaysia) translated from Chinese by Natascha Bruce (Granta Publications, 2019)

Lake Like a Mirror by Ho Sok Fong (Malaysia) translated from Chinese by Natascha Bruce (Granta Publications, 2019) Letters from Tove by Tove Jansson (Finland) edited by Boel Westin & Helen Svensson, translated from Swedish by Sarah Death (Sort of Books, 2019)

Letters from Tove by Tove Jansson (Finland) edited by Boel Westin & Helen Svensson, translated from Swedish by Sarah Death (Sort of Books, 2019) The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (Georgia/Germany), translated from German by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin (Scribe UK, 2019)

The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (Georgia/Germany), translated from German by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin (Scribe UK, 2019) Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun (Sudan), translated from Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette (Comma Press, 2019)

Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun (Sudan), translated from Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette (Comma Press, 2019) White Horse by Yan Ge (China), translated from Chinese by Nicky Harman (HopeRoad, 2019)

White Horse by Yan Ge (China), translated from Chinese by Nicky Harman (HopeRoad, 2019) Isabella (Smokestack Books, 2019), a collection of fiercely feminist poems by the Italian Renaissance writer Isabella Morra translated by Caroline Maldonado

Isabella (Smokestack Books, 2019), a collection of fiercely feminist poems by the Italian Renaissance writer Isabella Morra translated by Caroline Maldonado the extraordinary memoir about mushrooms and grief, The Way Through the Woods (Scribe UK, 2019) by Malaysian-born Long Litt Woon, translated from Norwegian by Barbara Haveland

the extraordinary memoir about mushrooms and grief, The Way Through the Woods (Scribe UK, 2019) by Malaysian-born Long Litt Woon, translated from Norwegian by Barbara Haveland and the pacey young adult thriller set in a small French town rife with racism and rage Summer of Reckoning (Bitter Lemon Press, 2020) by Marion Brunet, translated from French by Katherine Gregor.

and the pacey young adult thriller set in a small French town rife with racism and rage Summer of Reckoning (Bitter Lemon Press, 2020) by Marion Brunet, translated from French by Katherine Gregor.