We are just coming out of our second summer heatwave and in this kind of heat, where it’s 38°C (100°F) every afternoon, reading needs to be light and propulsive, because the brain just doesn’t function in the same way.

I chose to read French author Virginie Grimaldi’s All That Remains because I felt sure it would provide the sustenance I was looking for, without having to think too much.

Good-hearted, uplifting fiction, great characters and a connection with some of the best parts of French life, that help overcome universal problems that anyone might face. Positive aspects of humanity overcoming the oppressive.

I love the sprigs of mimosa on the book cover, a beautiful winter flowering shrub that thrives in difficult conditions, blooming on the coastal region of the south of France in January and February. It evokes such good feeling, symbolising new beginnings, resilience and adaptability and a sign that spring is on its way.

La Cohabitation Intergénérationnelle

In addition, when I read the premise of three generations living together, it reminded me of a news item I had seen on French television about “La cohabitation intergénérationnelle“, where residents (over 60 years) in Paris and elsewhere, at risk of needing to move out of their apartments or homes, were being matched with students (under 30 years) seeking affordable accommodation, able to be a reassuring presence, particularly at night, and share meals together.

Seeing these people on the screen, sitting talking together, feeling safer at home, having more space, companionship – able to get through those years of difficulty – well, as we say here, « Vive la France »!

Grief, Homelessness and New Beginnings

It’s a novel about three people from three different generations, who wind up sharing an apartment together, when their needs intersect.

Jeanne (74) is recovering from unexpected widowhood and needs to do something soon to address unforeseen financial concerns, if she wants to remain in her apartment in Paris. The woman in the bakery won’t allow her to put up a notice, but fortunately someone overhears her asking.

For the past three months, Jeanne had been unweaving those habits, thread by thread. The plural had become singular. The setting was the same, the timing the same, and yet everything rang hollow. Even the melancholy had disappeared, as if her entire life had been training for the bereavement she was now facing. She was desensitized.

Iris (33) a care worker, is being evicted from her temporary studio, living out of a suitcase and in hiding from a situation that will be revealed.

“Hello Madame, I just wanted to confirm my interest in your room for rent. And please know that, if it weren’t for my tricky situation, I’d never have interrupted your conversation with the young man, who also seems in real need of a home. If you’ve not yet made your choice, I’d understand if you favour him. Regards Iris.”

Théo (18) is an apprentice in a local boulangerie (bakery) and has just reached the age of independence. Having just bought a car for €200, he parked up outside the house with the blue shutters and thought he’d solved his accommodation woes, however his problems have just magnified.

I don’t intend to drive around in this car. I settle down on the back seat, head resting on my bag, covered with my coat. I put in my earbuds and play Grand Corps Malade’s latest song. I light the roll-up saved since this morning and close my eyes. It’s a long time since I’ve felt this good. No sleeping in the metro for me tonight. For 200 euros, I’ve treated myself to a home.

Jeanne, Iris and Théo in Paris

Each short chapter moves to the next character and within very few pages I was deeply invested in wanting to know more about each one and where the story was going. It’s a wonderful novel about perseverance and overcoming challenges and the messiness of life and finding support and comradeship in unexpected places.

I loved this book and would be not be surprised to see it being made into a film, it’s got all the good vibes and realistic issues that people f all generations have to face, and a unique but encouraging way that different members of a society can be there for those who were strangers at first.

Another #WITMonth read, highly recommended!

There is a crack in everything,

That’s how the light gets in.

LEONARD COHEN

Author, Virginie Grimaldi

Virginie Grimaldi was born in 1977 in Bordeaux where she still lives. Translated into more than twenty languages, her novels are carried by endearing characters and a poetic and sensitive pen. Her stories, funny and moving, echo everyone’s life. She is the most read French novelist in 2019, 2020 and 2021 (Le Figaro littéraire/GFK awards) and winner of the Favorite Book of the French in 2022 (France Télévisions).

N.B. Thank you kindly to Europa Editions UK for sending this copy for review.

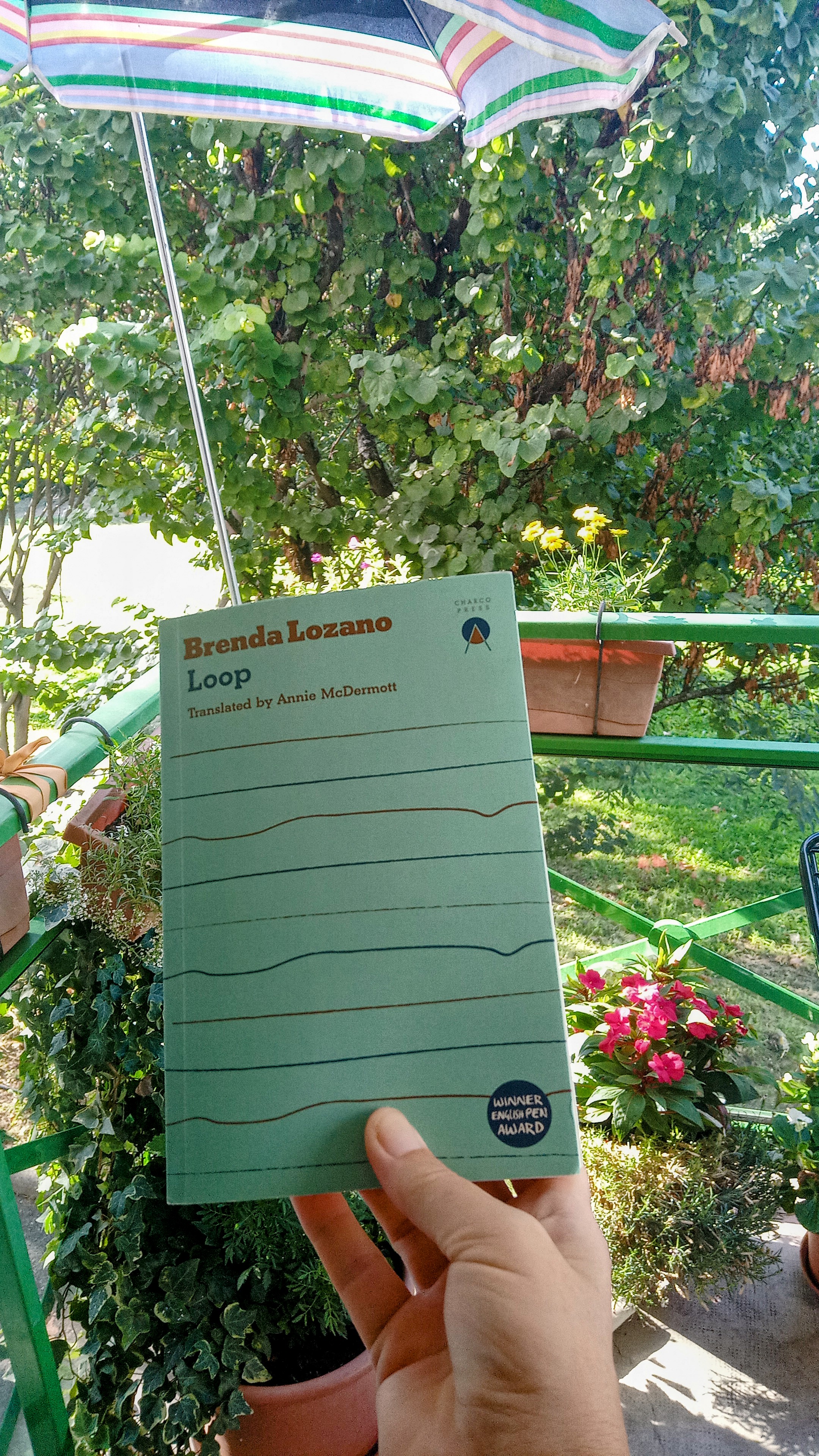

I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style.

I picked up Loop for WIT (Women in Translation) month and I loved it. I had few expectations going into reading it and was delightfully surprised by how much I enjoyed its unique, meandering, playful style. The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother.

The narrator is waiting for the return of her boyfriend, who has travelled to Spain after the death of his mother. A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both

A celebration of the yin aspect of life, the jewel within. And that jewel of a song, sung by both  Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981.

Brenda Lozano is a novelist, essayist and editor. She was born in Mexico in 1981. My final read of August for WITMonth was The Party Wall, French Canadian author Catherine Leroux’s third novel. It was shortlisted for the

My final read of August for WITMonth was The Party Wall, French Canadian author Catherine Leroux’s third novel. It was shortlisted for the

The last nonfiction book I read was also set in Morocco (at the time referred to as the Spanish Sahara) written by a foreign woman living openly with her boyfriend, it couldn’t be more in contrast with what I’ve just read here – although Sanmao does encounter women living within the oppressive system that is at work in this collection.

The last nonfiction book I read was also set in Morocco (at the time referred to as the Spanish Sahara) written by a foreign woman living openly with her boyfriend, it couldn’t be more in contrast with what I’ve just read here – although Sanmao does encounter women living within the oppressive system that is at work in this collection.

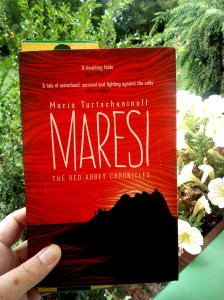

Naondel is the name of the ship that will bring the First Women to the island of Menos.

Naondel is the name of the ship that will bring the First Women to the island of Menos. The darkness these women endure, the evil that is perpetuated by their ruler, is only alleviated by the foreknowledge that we already know these women will eventually escape it. So we read in anticipation of that event, in the meantime getting to know each of them and the powers they had before they were enslaved.

The darkness these women endure, the evil that is perpetuated by their ruler, is only alleviated by the foreknowledge that we already know these women will eventually escape it. So we read in anticipation of that event, in the meantime getting to know each of them and the powers they had before they were enslaved. Red Abbey is situated on the island Menos, run by women, a kind of educational refuge that has elements of sounding like a boarding school and a convent. On the mainland some are not even sure if it is myth or reality, but they send their girls there in hope that the rumours are trues. We learn that Maresi was sent there by her family during ‘Hunger Winter’ and that the abundance of food, the genuine care and education she is given makes it a place she adores.

Red Abbey is situated on the island Menos, run by women, a kind of educational refuge that has elements of sounding like a boarding school and a convent. On the mainland some are not even sure if it is myth or reality, but they send their girls there in hope that the rumours are trues. We learn that Maresi was sent there by her family during ‘Hunger Winter’ and that the abundance of food, the genuine care and education she is given makes it a place she adores. There are two maps at the front of the book, one of Red Abbey, a walled area showing various buildings, such as Novice House, Knowledge House, Body’s Spring, Temple of the Rose, named steps and courtyards and a map of the island drawn by ‘Sister 0 in the second year of the reign of our thirty-second mother, based on the original by ‘Garai of the Blood in the reign of First Mother’

There are two maps at the front of the book, one of Red Abbey, a walled area showing various buildings, such as Novice House, Knowledge House, Body’s Spring, Temple of the Rose, named steps and courtyards and a map of the island drawn by ‘Sister 0 in the second year of the reign of our thirty-second mother, based on the original by ‘Garai of the Blood in the reign of First Mother’

Maryse Condé is one of my favourite authors and I’ve been slowly working my way through her books since she was nominated for the

Maryse Condé is one of my favourite authors and I’ve been slowly working my way through her books since she was nominated for the