translated by Fiona Mackintosh and Iona Macintyre

Wow. This is quietly revolutionary. And funny. Educational. Expansive. Luminous. Brilliant.

I want it to win.

Drawing inspiration from other texts that have in turn been inspired by a life, or experience lived in Argentina, whether the epic poem ‘the gaucho’ Martin Fierro by José Hernández (a lament for a disappearing way of life) or the autobiography Far Away & Long Ago of the naturalist William Henry Hudson, The Adventures of China Iron is a beautiful elegy (for there will be consolation), a brilliant feat of the imagination that takes readers on an alternative journey.

Drawing inspiration from other texts that have in turn been inspired by a life, or experience lived in Argentina, whether the epic poem ‘the gaucho’ Martin Fierro by José Hernández (a lament for a disappearing way of life) or the autobiography Far Away & Long Ago of the naturalist William Henry Hudson, The Adventures of China Iron is a beautiful elegy (for there will be consolation), a brilliant feat of the imagination that takes readers on an alternative journey.

Review

China Iron, wife of Martin Fierro, who in the original version was given just a few lines, is now the lead and is about to awaken to all that is and can be.

Her adventure is a heroine’s journey from dystopia to utopia, from naive to knowledgeable, from woman to young brother to lover, from unconscious to awakened, from surviving to aware to thriving.

While I was writing I felt I was describing the mind-blowing experience of being a newborn since in China’s eyes everything is new and has the shape and shininess of a new discovery. She is trying out her freedom, travelling for the first time, leaving the tiny settlement in which she had spent her whole life. She is discovering the world, the different paths through it, love. Gabriela Cabezón Cámara

Part One – The Pampas

China was passed over to Martin Fierro in holy matrimony in a card game. She bore him two children before he was conscripted, what a relief. Scottish Liz had her husband Oscar taken in error, so she packs a wagon to go and find the land they’ve procured, taking China and the dog Estreya with her. This is the beginning of China’s awakening, she will learn from Liz and being in nature, on the move.

Who knows what storms Liz had weathered. Maybe loneliness. She had two missions in life: to resuce her gringo husband and to take charge of the estancia they they were to oversee.

Liz informs China about the ways of the British Empire, clothing, manners, geography, Indian spices, African masks. Some things she understands, others take longer to reconcile. She discovers ‘a birds eye view’ from up there on the wagon.

And I began to see other perspectives: the Queen of England – a rich, powerful woman who owned millions of people’s lives, but who was sick and tired of jewels and of meals in palaces built where she was monarch of all she surveyed – didn’t see the world in the same way as, for example a gaucho in his hovel with his leather hides who burns dung to keep warm.

For the Queen the world was a sphere filled with riches belonging to her, and that she could order to be extracted from anywhere; for the gaucho, the world was a flat surface where you galloped around rounding up cows, cutting the throats of your enemies before they cut your own throat, or fleeing conscription or battles.

China leaves behind neglect and enters the realm of non-violent company, nourishment and knowledge. She comes to think of the wagon as home and falls for Liz’s charm. They track Indians by examining the dung of their animals. When they see it’s fresh, they stop and change.

I took off my dress and the petticoats and I put on the Englishman’s breeches and shirt. I put on his neckerchief and asked Liz to cut my hair short. My plait fell to the ground and there I was, a young lad.

Photo by Juanjo Menta on Pexels.com

They encounter a lone gaucho (cowboy) Rosario and his herd of cows, he becomes the fourth member of their party. We learn his tragic backstory as well. He laughs at China’s clothing, but says it’s a good idea and that all women should carry a knife the way men do.

We knew he was talking about his mother and how he’d have preferred her to have grown a beard if it meant she’d have stayed a widow with him by her side instead of that monster.

They make slow progress, in part due to China’s desire that this in-between peaceful co-existence, the happiest she’s ever experienced, never ends.

Part Two, The Fort

They arrive at the estancia run by Hernandez, they dress in their chosen uniforms Liz had allocated from the stores inside the wagon;

uniforms for every kind of position on the estancia according to the imagination of the aristocrat and his stewards, Liz and Oscar.

Here they come across the opposite of what they’d found in the plains, here is a world run by the self-righteous Hernandez, who runs his estancia like a dictatorial regime, with strict rules and regulation, reward and punishment, inspiring hatred and allowing revenge. Seeing himself as the seed of civilisation, others as savages with no sense of history and the gauchos as his protegé, he sets out to retrain them in his ways, with a whip and a rod.

Photo by Artem Beliaikin on Pexels.com

Part Three – Indian Territory

In the final part they come into contact with the indigenous population and even the air feels easier to breathe. Here the language changes, perception changes, there is acceptance, equilibrium, reunion.

This whole section reminded me of the shape-shifting shamans, of a higher perception or consciousness, living with the indigenous people allows them to let go of all expectations and see with different eyes.

“Although we have been made

to believe that if we let go

we will end up with nothing,

life reveals just the opposite:

that letting go is

the real path to freedom.”

– Soygyal Rinpoche

I absolutely loved this, I hope it wins the International Booker 2020 thoroughly deserving in my opinion.

Ever since I had the idea of giving China a voice, I had one thing clear in my mind: I wanted her tale to be an experience of the beauty of nature, freedom in body and mind; a story of all the potential and possibilities in store when you encounter other people, of the beauty of light. I wanted to write an elegy to the flora and fauna of Argentina, or whatever is left of it, an elegy to what used to be here before it all got transformed into one big grim factory poisoned with pesticides. I wanted to write a novel infused with light. Gabriela Cabezón Cámara

Further Reading

Interview: International Booker Prize 2020 Interview with author and translators

I have wanted to read this novel for a while, ever since reading

I have wanted to read this novel for a while, ever since reading

Meytal Radzinski, the founder of #WITMonth, an initiative to encourage people to read more books by women that have been translated from another language, therefore promoting diversity, has asked readers to share their top 10 ten books by women writers in translation.

Meytal Radzinski, the founder of #WITMonth, an initiative to encourage people to read more books by women that have been translated from another language, therefore promoting diversity, has asked readers to share their top 10 ten books by women writers in translation. 1.

1.  2.

2.  3.

3.  4.

4.  5.

5.  6.

6.  7.

7.  8.

8.  9.

9.  10.

10.

The Gold Letter is a story of Greek families living in what was then known as Constantinople (later renamed as Istanbul, one of many name changes – The city was founded in 667 BC and named Byzantium by the Greeks ), and how the same twist of fate affects three generations of the same two families, where a young woman and a young man fall in love, only to have the union thwarted by their parents – in each generation it is for a different reason, beginning with them not being of the same wealth and social status, where marriage was more of a contract between families decided by the father’s.

The Gold Letter is a story of Greek families living in what was then known as Constantinople (later renamed as Istanbul, one of many name changes – The city was founded in 667 BC and named Byzantium by the Greeks ), and how the same twist of fate affects three generations of the same two families, where a young woman and a young man fall in love, only to have the union thwarted by their parents – in each generation it is for a different reason, beginning with them not being of the same wealth and social status, where marriage was more of a contract between families decided by the father’s.

I was reminded of the wonderful novel about a friendship between two children in the same village, one of Greek and one of Turkish origin by

I was reminded of the wonderful novel about a friendship between two children in the same village, one of Greek and one of Turkish origin by  The reason they are highlighted in August is an attempt to raise awareness of the very narrow choice we give ourselves by only reading books in English, or from one’s own country and to highlight the fact that even when we do read outside our first language, the majority of books published, promoted and reviewed are written by men.

The reason they are highlighted in August is an attempt to raise awareness of the very narrow choice we give ourselves by only reading books in English, or from one’s own country and to highlight the fact that even when we do read outside our first language, the majority of books published, promoted and reviewed are written by men.

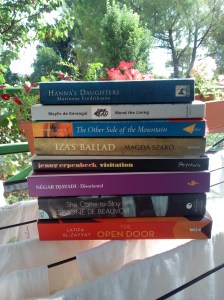

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir Hanna has one daughter, Johanna, a name that carries its own story and past, before she is even born, one of the reasons she is closer to her father in her early years. Johanna would also have one daughter Anna, it is she who begins to narrate this story, she visits her mother in hospital, desperate to get answers to questions she has left it too late to ask.

Hanna has one daughter, Johanna, a name that carries its own story and past, before she is even born, one of the reasons she is closer to her father in her early years. Johanna would also have one daughter Anna, it is she who begins to narrate this story, she visits her mother in hospital, desperate to get answers to questions she has left it too late to ask. The first half of the book is dedicated to Hanna and her life and this is where the novel is at its best, immersed in the struggle of Hanna’s early years, its tragic turning point and the situation she is forced to accept as a result. Circumstances that will become buried deep, that nevertheless leave their impression on how she is in the world and impact those daughters indirectly.

The first half of the book is dedicated to Hanna and her life and this is where the novel is at its best, immersed in the struggle of Hanna’s early years, its tragic turning point and the situation she is forced to accept as a result. Circumstances that will become buried deep, that nevertheless leave their impression on how she is in the world and impact those daughters indirectly.

The Other Side of the Mountain by Erendiz Atasü is one of those books I came across in a blog post I read in 2017, a post entitled

The Other Side of the Mountain by Erendiz Atasü is one of those books I came across in a blog post I read in 2017, a post entitled

I’m glad The Open Door was brought back into publication, it was a landmark work in woman’s writing in Arabic when it was first published in 1960, an important commentary on the challenges women and girls in so many societies face, a consequence of patriarchy; an effect that is being busted wide open today, forcing transparency, offering support, healing and with hope, gradual change in many countries today. It seems timely to revisit this, or to read it for the first time, as will likely be the case for many.

I’m glad The Open Door was brought back into publication, it was a landmark work in woman’s writing in Arabic when it was first published in 1960, an important commentary on the challenges women and girls in so many societies face, a consequence of patriarchy; an effect that is being busted wide open today, forcing transparency, offering support, healing and with hope, gradual change in many countries today. It seems timely to revisit this, or to read it for the first time, as will likely be the case for many.

About her novel, she had this to say:

About her novel, she had this to say:

The narrating of family stories, taking us back as far as her great-grandfather Montazemolmolk with his harem of 52 wives, serves to provide context and an explanation for why certain family members might have behaved or lived in the way they did, helping us understand their motives and actions.

The narrating of family stories, taking us back as far as her great-grandfather Montazemolmolk with his harem of 52 wives, serves to provide context and an explanation for why certain family members might have behaved or lived in the way they did, helping us understand their motives and actions.

I’ve attempted to read Visitation about four times and never succeeded in getting past the first few chapters, but this year I persevered as I felt I hadn’t given it a fair chance.

I’ve attempted to read Visitation about four times and never succeeded in getting past the first few chapters, but this year I persevered as I felt I hadn’t given it a fair chance.