Marysé Conde is a Guadeloupean writer I came across in 2015 when she was nominated for the Man Booker International Prize, at a time when it was a two yearly prize for a lifetime’s work.

It has now evolved into an annual prize split between the author and translator for a book translated into English that year and in 2016 it was awarded to Han Kang (South Korea) and Deborah Smith (translator) for the novel The Vegetarian.

Maryse Condé didn’t win the prize back in 2015, but was the author on the list who most appealed to me.

- Maryse Condé

Since reading about her at that time, I followed her own recommendations in terms of what to read to be introduced to her work, starting with a collection of vignettes in Tales from the Heart: True Stories from my Childhood, then Victoire: My Mother’s Mother and finally, the grand masterpiece and novel she is most well-known for, especially in academic circles, as it is widely studied and recognised as an important work of historical fiction set in the African Kingdom during a significant period of change: Segu.

I’ve wanted to read more of her work, so tracked down a couple more books that have been translated into English and was fortunate enough to have listened to her speak at our local library earlier this year – though she lived in France for many years, she is now retired and has returned to her native Guadeloupe to live, though still active in literary circles.

A Season in Rihata – review

Zek and his Guadeloupean wife Marie-Hélène live in a small fictitious African town of Rihata, with their six children and another due any day. It is far from Paris where they met and lived in very different way and far removed from the kind of life Marie-Hélène’s remembers on the island home of her childhood.

Like all men of his ethnic group, Zek had been brought up with a kind of fear and contempt of woman – malevolent creatures whose dark instincts had to be mastered. Love had taken him by surprise. He had difficulty accepting the power Marie-Hélène held over him and was convinced that no other man except him had undergone such humiliation.

Neither are happy; Zek has never been able to get over the feeling of being looked down on by his father, even though he is long dead, and remains resentful of his younger brother Madou, who found favour without having to do anything and who was the cause of him having to relocate his family due to the unwanted attentions of his brother towards his wife.

Influenced by a father who made no pretence of his preferences, Madou had soon considered Zek as a person of limited ability and in all ways inferior; although this did not exclude a certain brotherly affection.

Now Madou is coming to Rihata, he is a political Minister coming to conduct negotiations, his presence causing many to feel uneasy, a disruption in the sleepy town where not much usually happens.

It is a novel of discontent, of the effects of selfish behaviour, which none are immune to or able to rise above. Contentedness is within their reach, but so is temptation and the effect of indulging it ricochets through all members of the extended family and the rulers of the country.

While it doesn’t reach the heights of her other work I’ve read, it’s a worthy contribution to her body of literature and I look forward to reading more.

On the day when the nation is shocked and grieving after a devastating earthquake, that has destroyed entire villages and resulted in a significant loss of life, I don’t know how appropriate it is to share their literature, perhaps in the case of this particular novel, it serves to put things in perspective.

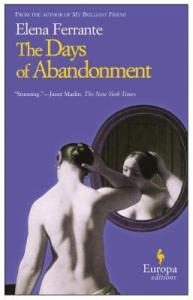

On the day when the nation is shocked and grieving after a devastating earthquake, that has destroyed entire villages and resulted in a significant loss of life, I don’t know how appropriate it is to share their literature, perhaps in the case of this particular novel, it serves to put things in perspective. A national bestseller for almost an entire year, The Days of Abandonment shocked and captivated its Italian public when first published.

A national bestseller for almost an entire year, The Days of Abandonment shocked and captivated its Italian public when first published.

From her early days, Firdaus was a child who was noticed, though rarely looked out for, instances of cruelty and neglect made up the patchwork of her childhood. “Rescued” by an Uncle who’d already crossed filial boundaries, her one respite was to have been sent by him to school, his new wife further insisting she live there, perhaps the only paradisiacal period of her life, the one time she was left alone to flourish, to evolve, gaining her secondary school certificate, her sole prized possession.

From her early days, Firdaus was a child who was noticed, though rarely looked out for, instances of cruelty and neglect made up the patchwork of her childhood. “Rescued” by an Uncle who’d already crossed filial boundaries, her one respite was to have been sent by him to school, his new wife further insisting she live there, perhaps the only paradisiacal period of her life, the one time she was left alone to flourish, to evolve, gaining her secondary school certificate, her sole prized possession. Selected in 2010 as one of The Best of Young Spanish Language Novelists by

Selected in 2010 as one of The Best of Young Spanish Language Novelists by

Rachel Cooke in this Guardian article

Rachel Cooke in this Guardian article

It should have been perfect, but things change when an old friend of her mother’s Anne arrives and she and her father announce their intention to marry. Although it is actually something Cecile feels is right for them and she adores Anne, part of her resents what signifies to her the end to the playful era she and her father have indulged, for Anne’s presence in their lives will certainly bring order and sensibility.

It should have been perfect, but things change when an old friend of her mother’s Anne arrives and she and her father announce their intention to marry. Although it is actually something Cecile feels is right for them and she adores Anne, part of her resents what signifies to her the end to the playful era she and her father have indulged, for Anne’s presence in their lives will certainly bring order and sensibility. It is 1947, in the province of Punjab, which sits between India and Pakistan, an area where Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and others live side by side. Tension is mounting as political events cause rifts between friends and neighbours as many of the Muslim population support the area becoming part of Pakistan and many Hindu fear for their lives, while the same tensions exist among Muslims living in the predominantly Hindu parts of India.

It is 1947, in the province of Punjab, which sits between India and Pakistan, an area where Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and others live side by side. Tension is mounting as political events cause rifts between friends and neighbours as many of the Muslim population support the area becoming part of Pakistan and many Hindu fear for their lives, while the same tensions exist among Muslims living in the predominantly Hindu parts of India. The thing they all fear most, that some desire most happens and Asha’s family leave their past behind and head for Delhi. Firoze helps them to escape and Asha leaves with a secret she has kept from everyone, the future unknown.

The thing they all fear most, that some desire most happens and Asha’s family leave their past behind and head for Delhi. Firoze helps them to escape and Asha leaves with a secret she has kept from everyone, the future unknown.

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche.

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche. It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese.

It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese. Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors.

Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors. Absolutely brilliant, astonishing, loved it, one of my Top Reads of 2016 for sure.

Absolutely brilliant, astonishing, loved it, one of my Top Reads of 2016 for sure.

The novel is predominantly a second person narrative addressed to Elijah, long after she has lost him, narrating the events of their meeting, her pursuit of the dinosaur fossils straight after meeting him, her return to Dhaka and then her escape from her family to Chittagong, to work alongside a female film-maker interviewing workers on the ship graveyards, beaches where enormous liners are dismantled and parts recycled.

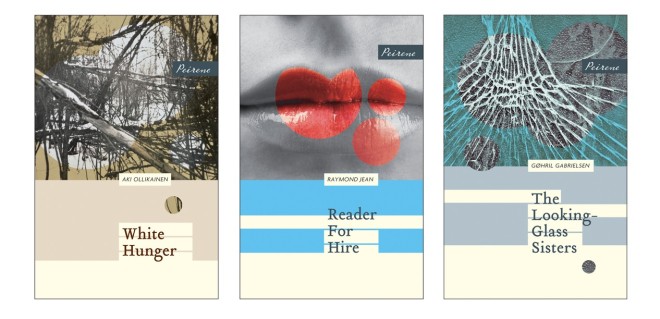

The novel is predominantly a second person narrative addressed to Elijah, long after she has lost him, narrating the events of their meeting, her pursuit of the dinosaur fossils straight after meeting him, her return to Dhaka and then her escape from her family to Chittagong, to work alongside a female film-maker interviewing workers on the ship graveyards, beaches where enormous liners are dismantled and parts recycled. Two sisters have lived in the same house all their lives, their parents long gone and they can barely tolerate each other. They are bound together in one sense due to the practical disability of the younger sister, but also through the inherent sense of duty and responsibility of the first-born.

Two sisters have lived in the same house all their lives, their parents long gone and they can barely tolerate each other. They are bound together in one sense due to the practical disability of the younger sister, but also through the inherent sense of duty and responsibility of the first-born.