Happiness opens with the tale of a wolf hunter in the US called in to track a wolf that is believed to have been killing sheep. He observes the surroundings, lies in wait, makes the kill, collects his bounty and then returns to lie in wait for the she-wolf he knows will come out after three days. Two species. Surviving.

Happiness opens with the tale of a wolf hunter in the US called in to track a wolf that is believed to have been killing sheep. He observes the surroundings, lies in wait, makes the kill, collects his bounty and then returns to lie in wait for the she-wolf he knows will come out after three days. Two species. Surviving.

London. A fox makes its way across Waterloo Bridge. The distraction causes two pedestrians to collide—Jean, an American studying the habits of urban foxes, and Attila, a Ghanaian psychiatrist there to deliver a keynote speech.

Attila has just been to the theatre, he has arrived a few days early to indulge his passion for theatre and to look up his niece Ama, whom the family hasn’t heard from recently, he will also see an old friend and former colleague Rosie, who has premature Alzheimers.

While we follow Attila on his rounds of visiting his friends and family, all of whom are in need of his aide, we witness flashbacks into his working life, his brief encounters in numerous war zones, where he was sent on missions to negotiate with hardline individuals often operating outside the law. He remembers his wife Maryse, there is deep sense of remorse.

His niece Ama and her 10 year old son Tano have been forcibly evicted from their apartment in an immigration crackdown, she is unable to resolve the matter, hospitalised due to an unstable diabetic condition. Attila responds with the help of the doorman of his hotel, who alerts other hotel doormen, to be on the lookout for Tano who has disappeared amidst all the confusion.

And there is Jean, in London to study the behaviour of the urban fox, she has funding for a period of time to observe them, their numbers, how they have come to be living in the city and whether they expose a risk to the humans they live alongside. She recruited a local street-cleaner and through him others, to be her field study fox spotters, the few people likely to regularly see them.

‘Everything happens for a reason, that was Jean’s view, and part of her job was tracing those chains of cause and effect, mapping the interconnectedness of things.’

These networks of connected men, the doormen, the streetcleaners and others, come together to help Jean and Attila in their search for Tano. They’ve texted his picture to each other, they know who to look for. They demonstrate something important, in their resilience and ability to adapt to this new environment, creating new support circles, many having been through traumatic experiences before finding a semblance of new life in London.

‘Let me do the same for you,’ said the doorman. ‘The doormen and security people, they are my friends. Most of those boys who work in security are Nigerian. We Ghanaians, we prefer the hospitality industry. Many of the doormen at these hotels you see around here are our countrymen. The street-sweepers, the traffic wardens are mainly boys from Sierra Leone, they came here after their war so for them the work is okay.’

The fox lives beside the human but inhabits a different time zone, most humans are little aware of their presence as their nocturnal meanderings cease the minute humanity awakens and begins to disturb a territory that belongs more to them in the small hours of the night.

The fox lives beside the human but inhabits a different time zone, most humans are little aware of their presence as their nocturnal meanderings cease the minute humanity awakens and begins to disturb a territory that belongs more to them in the small hours of the night.

Jean too remembers what she has left, in America, where she tried to do a similar study on the coyote, an animal that due to the human impact on the environment had left the prairie and moved towards more urban environment.

Finding herself in conflict with locals, who campaigned against the coyote, believing it to be a danger to humans, her voice silenced by those who preferred to extend hunting licences, despite her warnings that culling the coyote would result in their population multiplying not decreasing.

‘If you remove a coyote from a territory, by whatever means, say even if one dies of natural causes a space opens up. Another will move in.’

‘What if you were to kill a number of them, ten per cent of the total population, say?’

‘They’d reproduce at a faster rate. We call it hyper-reproduction. Have larger litters of cubs. Begin to mate younger, at a year instead of at two years. All animals do it, not just coyote,’ said Jean. ‘Humans do it after a war. The last time it happened we called it the ‘baby boom”.’

Now a similar debate arises in London, where the Mayor wants to cull the animals and Jean’s message, based on scientific evidence is being ignored, worse it attracts the attention of internet trolls, flaming the unsubstantiated fears of residents.

UK Cover

Ultimately the novel is about how we all adapt, humans and wild animals alike, to changing circumstances, to trauma, to the environment; that we can overcome the trauma, however we need to be aware of those who have adapted long before us, who will resist the newcomer, the propaganda within a political message.

And to the possibility that the experience of trauma doesn’t have to equate to continual suffering, that our narrative does not have to be that which happened in the past, it is possible to change, to move on, to find community in another place, to rebuild, to have hope. And that is perhaps what happiness really is, a space where hope can grow, might exist, not the fulfilment of, but the idea, the expression.

Hope. Humour. Survival.

Salman Rushdie alludes to this after the fatwa was issued against him when he said this:

“Those who do not have power over the story that dominates their lives, power to retell it, rethink it, deconstruct it, joke about it, and change it as times change, truly are powerless, because they cannot think new thoughts.”

Aminatta Forna

In an enlightening article in The Guardian, linked below, Forna describes reading Resilience, by renowned psychologist Boris Cyrulnik. Born in France in 1937, his parents were sent to concentration camps in WW2 and never returned. He survived, but his story often wasn’t believed, it didn’t fit the narrative of the time. He studied medicine and became a specialist in resilience.

“It’s not so much that I have new ideas,” he says, at pains to acknowledge his debt to other psychoanalytic thinkers, “but I do offer a new attitude. Resilience is about abandoning the imprint of the past.”

The most important thing to note about his work, he says, is that resilience is not a character trait: people are not born more, or less, resilient than others. As he writes: “Resilience is a mesh, not a substance. We are forced to knit ourselves, using the people and things we meet in our emotional and social environments.

Further Reading

My Review: The Memory of Love by Aminatta Forna

My Review: The Hired Man by Aminatta Forna

Article: Aminatta Forna: ‘We must take back our stories and reverse the gaze’, Writers of African heritage must resist the attempts of others to define us and our history, Feb 2017

Article: Escape from the past: Boris Cyrulnik lost his mother and father in the Holocaust. But childhood trauma needn’t be a burden, he argues – it can be the making of us. by Viv Groskop Apr 2009

***

Note: This book was an ARC, kindly provided by the publisher (Grove Atlantic) via NetGalley. It is published March 6 in the US and 5 April in the UK.

Buy a copy of Happiness via BookDepository

There is something so captivating about the voice of Lucy Barton, it made me wish to slow read this novel, as if it were a box of exquisite chocolates that require enormous self-discipline not to finish in one sitting.

There is something so captivating about the voice of Lucy Barton, it made me wish to slow read this novel, as if it were a box of exquisite chocolates that require enormous self-discipline not to finish in one sitting. Absolutely loved it, hypnotic, slowly affirming a life that can grow and change and evolve out of traumatic experience, that past narratives don’t define future stories, that love is as hardy as a seed that grows out of rock, not impossible to bloom even in the harshest of circumstances.

Absolutely loved it, hypnotic, slowly affirming a life that can grow and change and evolve out of traumatic experience, that past narratives don’t define future stories, that love is as hardy as a seed that grows out of rock, not impossible to bloom even in the harshest of circumstances. The first woman who came to mind and whose book I want to recommend is Wangari Maathai’s Unbowed, One Woman’s Story. Kenyan and one of a group of young African’s selected to be part of the ‘Kennedy Airlift’ , she and others were given the opportunity to gain higher education in the US and to use their education to contribute to progress in their home countries. Maathai was a scientist, an academic and an activist, passionate about sustainable development; she started the The Greenbelt Movement, a tree planting initiative, which not only helped save the land, but empowered local women to take charge of creating nurseries in their villages, thereby taking care of their own and their family’s well-being.

The first woman who came to mind and whose book I want to recommend is Wangari Maathai’s Unbowed, One Woman’s Story. Kenyan and one of a group of young African’s selected to be part of the ‘Kennedy Airlift’ , she and others were given the opportunity to gain higher education in the US and to use their education to contribute to progress in their home countries. Maathai was a scientist, an academic and an activist, passionate about sustainable development; she started the The Greenbelt Movement, a tree planting initiative, which not only helped save the land, but empowered local women to take charge of creating nurseries in their villages, thereby taking care of their own and their family’s well-being. Henrietta Lacks is perhaps one of the most famous women we’d never heard of, a woman who never knew or benefited from her incredible contribution to science and humanity. A young mother in her 30’s, she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer and despite being eligible for and receiving medical care at the John Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, a medical facility funded and founded to ensure equal access no matter their race, status, income or other discriminatory reason, she died soon after.

Henrietta Lacks is perhaps one of the most famous women we’d never heard of, a woman who never knew or benefited from her incredible contribution to science and humanity. A young mother in her 30’s, she was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer and despite being eligible for and receiving medical care at the John Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, a medical facility funded and founded to ensure equal access no matter their race, status, income or other discriminatory reason, she died soon after. Vera Brittain was a university student at Oxford when World War 1 began to decimate the lives of youth, family and friends around her. It suspended her education and resulted in her volunteering as a VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurse. Initially based in a military hospital in London, events would propel her to volunteer for a foreign assignment, taking her to Malta and then close to the front line in France for the remaining years of the war.

Vera Brittain was a university student at Oxford when World War 1 began to decimate the lives of youth, family and friends around her. It suspended her education and resulted in her volunteering as a VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurse. Initially based in a military hospital in London, events would propel her to volunteer for a foreign assignment, taking her to Malta and then close to the front line in France for the remaining years of the war. Maya Angelou is best known for her incredible series of seven autobiographies, beginning with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), narrating her life up to the age of 17. She became a writer after a number of varied occupations in her youth.

Maya Angelou is best known for her incredible series of seven autobiographies, beginning with I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), narrating her life up to the age of 17. She became a writer after a number of varied occupations in her youth. Diana Athill OBE (born 21 Dec 1917) is someone I think of as the ordinary made extraordinary. She was a fiction editor for most of her working life, forced into earning a living due to circumstance, for while her great-grandparents generation had made or married into money, her father’s generation lost it. She clearly remembers her father telling her ‘You will have to earn your living’ and that it was something almost unnatural at the time.

Diana Athill OBE (born 21 Dec 1917) is someone I think of as the ordinary made extraordinary. She was a fiction editor for most of her working life, forced into earning a living due to circumstance, for while her great-grandparents generation had made or married into money, her father’s generation lost it. She clearly remembers her father telling her ‘You will have to earn your living’ and that it was something almost unnatural at the time. So now it is 1869 in Albany, New York, Mary Sutter is now Dr Mary Sutter Stipps, living in Albany, New York, where she practices in a local hospital, despite most of her male colleagues despising her (because she is a woman), she also runs a home practice with her husband William Stipp and a lesser known clinic, where a lantern is illuminated on Thursdays when she opens for ladies of the night, those who are refused treatment elsewhere.

So now it is 1869 in Albany, New York, Mary Sutter is now Dr Mary Sutter Stipps, living in Albany, New York, where she practices in a local hospital, despite most of her male colleagues despising her (because she is a woman), she also runs a home practice with her husband William Stipp and a lesser known clinic, where a lantern is illuminated on Thursdays when she opens for ladies of the night, those who are refused treatment elsewhere.

In The Heart’s Invisible Furies, a title taken from a quote by Hannah Arendt, the German-born American political theorist:

In The Heart’s Invisible Furies, a title taken from a quote by Hannah Arendt, the German-born American political theorist:

Reservoir 13 was long listed for the

Reservoir 13 was long listed for the  This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness.

This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness. It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s

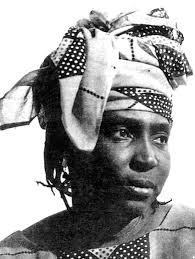

It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s  Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.

Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.

Once I got into the rhythm of this, which is to say, reading in French, and getting past the need to look up too many new words, I couldn’t put this down, by the time I found my reading rhythm, the lives of Gabriel (Gaby) and his sister Ana, his parents, his friends had their claws in me and I had to know what was going to happen next.

Once I got into the rhythm of this, which is to say, reading in French, and getting past the need to look up too many new words, I couldn’t put this down, by the time I found my reading rhythm, the lives of Gabriel (Gaby) and his sister Ana, his parents, his friends had their claws in me and I had to know what was going to happen next. His father is French, his mother Tutsi from Rwanda, they live in the small country bordering Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo, called Burundi. It boasts the second deepest lake in the world, Lake Tanganyika, which occupies a large portion of the country’s border and is part of the African Great Lakes region.

His father is French, his mother Tutsi from Rwanda, they live in the small country bordering Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo, called Burundi. It boasts the second deepest lake in the world, Lake Tanganyika, which occupies a large portion of the country’s border and is part of the African Great Lakes region.

The ending is not really an ending, it could be said there is more than one ending and perhaps there may even be another book. I found it incredibly moving and was amazed to be so moved in a language that is not my own. An incredible feat of writing, a wonderful talent.

The ending is not really an ending, it could be said there is more than one ending and perhaps there may even be another book. I found it incredibly moving and was amazed to be so moved in a language that is not my own. An incredible feat of writing, a wonderful talent. Sing, Unburied, Sing is set in the same Southern US community, putting us amidst a struggling mixed race family, a young black woman Leonie, who fell in love with Michael from a racist white family implicated in a tragedy that affected her family. In its telling, it traverses love, grief, terminal illness, addiction, prejudice, dysfunctional parenting, hope and survival, the effect this mix has on everyone touched by it, the painful and the poignant.

Sing, Unburied, Sing is set in the same Southern US community, putting us amidst a struggling mixed race family, a young black woman Leonie, who fell in love with Michael from a racist white family implicated in a tragedy that affected her family. In its telling, it traverses love, grief, terminal illness, addiction, prejudice, dysfunctional parenting, hope and survival, the effect this mix has on everyone touched by it, the painful and the poignant. There is a reference to her novel Salvage The Bones, as the family return from their road trip, they pass a young couple walking a dog, it is the brother and sister, Skeetah and Eschelle, from the neighbourhood, protagonists of that earlier novel. I was curious to know if the dog was related to China, an unresolved thread left hanging from her earlier novel. I was delighted to encounter them.

There is a reference to her novel Salvage The Bones, as the family return from their road trip, they pass a young couple walking a dog, it is the brother and sister, Skeetah and Eschelle, from the neighbourhood, protagonists of that earlier novel. I was curious to know if the dog was related to China, an unresolved thread left hanging from her earlier novel. I was delighted to encounter them.