From an extraordinary writer and storyteller who defies categorisation, another tale that stretches and flexes the readers imagination, hauntingly written, leaving me to wonder just how she does it, a thought I had after reading her novel, or story collection Revenge in 2013.

From an extraordinary writer and storyteller who defies categorisation, another tale that stretches and flexes the readers imagination, hauntingly written, leaving me to wonder just how she does it, a thought I had after reading her novel, or story collection Revenge in 2013.

The Memory Police are an oppressive, bureaucratic menace slowly making things on the island disappear along with all memories of them in the minds of inhabitants. And they enforce forgetfulness. Checking up on people to be sure memory has been erased, because though for most the memories disappear without effort, in some they linger. Those whose memory somehow stays intact live in danger, they begin to disappear, go in to hiding or are forcefully removed.

Our unnamed narrator has lost both her parents, taken by the police and no longer heard of; though her mother tried to preserve and hide some of the things that disappeared through her art. The daughter is a novelist, as long as words, imagination and voice exist she continues to write. She accepts her fate and continues to adapt to each disappearance with the help of an old man she is close to and the company of the neighbour’s dog, when its owners are removed.

Her editor R goes into hiding due to his ability to remember and tries to instill in her the importance and value of memories, while sometimes a memory returns, for her, it no longer has emotional significance or meaning. She possesses empathy but is void of nostalgia, without the objects the memories disappear and even when one reappears, it no longer evokes any emotion or feeling.

Gathering photographs (when they become the next thing to disappear) and albums to burn, R makes a desperate effort to stop her:

“Photographs are precious. If you burn them, there’s no getting them back. You mustn’t do this. Absolutely not.”

“But what can I do? The time has come for them to disappear,” I told him.

“They may be nothing more than scraps of paper, but they capture something profound. Light and wind and air, the tenderness or joy of the photographer, the bashfulness or pleasure of the subject. You have to guard these things forever in your heart. That’s why photographs are taken in the first place.”

It’s a dystopian novel that focuses more on the survival of the citizens than on exploring the tyranny that oppresses them, the Memory Police don’t seem to be afflicted with “forgetting” and we don’t understand what motivates them. Is it an allegory of collective degeneration, or an attempt to make the reader understand something that is universal among the aged? Suffering seems to rest with those to retain memory, those who forget adapt, and forget that they have forgotten.

There doesn’t seem to be any purpose, merely an exploration of those aspects of humanity of the oppressed to survive and care for one another, whether that means putting one’s life at risk to hide someone who does retain memories, to seek out old memories at the risk of being caught, caring for an old man and a dog.

Some things are innate to humanity and no matter what afflicts us, we are endlessly adaptable, continuing to find ways to work around and/or accept obstacles, here presented in a somewhat absurd manner, highlighting our inability to fight against adaptability. We have no choice but to adapt, it’s written into our genes, and this regime has somehow managed to find a way to control and rewrite them.

Alongside what is happening on the island’s (sur)real world, our protagonist writes a novel about a woman taking typing lessons from a man who will put her in a tower, these chapters are interspersed throughout the narrative and provide an alternative, thought-provoking aspect to the wider story.

When novels disappear and hers remains unfinished despite numerous attempts to write at the request of R, and a loss of inspiration, the old man asks her if it’s possible to write about something in a novel if you’ve never experienced it.

“I suppose it is. Even if you haven’t seen or heard about something, it seems you can just imagine it and then write it down? It doesn’t have to be exactly like the real thing; it’s apparently all right to make things up or even lie.”

“That’s right. Apparently no one blames you for lying in a novel. You can make up the story out of nothing, starting from zero. You write about something you can’t see as though you can see it. You make something that doesn’t exist just by using words. That’s why R says we shouldn’t give up, even if our memories disappear.”

Each disappearance activates the reader’s imagination and the novel provokes many questions that make this an interesting one to discuss.

It’s a novel that stayed with me long after reading, wondering what it was getting at; just as you think you’ve found some deeper meaner, it kind of gets erased, there are no easy conclusions…it’s like the advent of short term memory loss, a literary version of mild cognitive impairment, an affliction all humans post middle age experience and one this novel makes you experience what that might be like in reading. Astonishing.

Further Reading

The Guardian: The Memory Police by Yōko Ogawa review – profound allegory of loss by Madeleine Thien

NY Times Article: How “The Memory Police” makes you See by Jia Tolentino

Thanks to an email from Peirene Press this morning sharing news of the long list nomination of their novella Faces On the Tip of My Tongue by the French author Emmanuelle Pagano, I see that both The Memory Police and The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar have also been nominated for the International Booker 2020.

In yesterday’s post I mentioned I had just finished reading this book, a wonderful, if challenging work of translated fiction by the Iranian author Shokoofeh Azar, who lives in exile in Australia. This novel was shortlisted for the Stella Prize in 2018 (a literary award that celebrates Australian women’s writing and an organisation promoting cultural change).

In yesterday’s post I mentioned I had just finished reading this book, a wonderful, if challenging work of translated fiction by the Iranian author Shokoofeh Azar, who lives in exile in Australia. This novel was shortlisted for the Stella Prize in 2018 (a literary award that celebrates Australian women’s writing and an organisation promoting cultural change).

I have wanted to read this novel for a while, ever since reading

I have wanted to read this novel for a while, ever since reading

Meytal Radzinski, the founder of #WITMonth, an initiative to encourage people to read more books by women that have been translated from another language, therefore promoting diversity, has asked readers to share their top 10 ten books by women writers in translation.

Meytal Radzinski, the founder of #WITMonth, an initiative to encourage people to read more books by women that have been translated from another language, therefore promoting diversity, has asked readers to share their top 10 ten books by women writers in translation. 1.

1.  2.

2.  3.

3.  4.

4.  5.

5.  6.

6.  7.

7.  8.

8.  9.

9.  10.

10.

The Gold Letter is a story of Greek families living in what was then known as Constantinople (later renamed as Istanbul, one of many name changes – The city was founded in 667 BC and named Byzantium by the Greeks ), and how the same twist of fate affects three generations of the same two families, where a young woman and a young man fall in love, only to have the union thwarted by their parents – in each generation it is for a different reason, beginning with them not being of the same wealth and social status, where marriage was more of a contract between families decided by the father’s.

The Gold Letter is a story of Greek families living in what was then known as Constantinople (later renamed as Istanbul, one of many name changes – The city was founded in 667 BC and named Byzantium by the Greeks ), and how the same twist of fate affects three generations of the same two families, where a young woman and a young man fall in love, only to have the union thwarted by their parents – in each generation it is for a different reason, beginning with them not being of the same wealth and social status, where marriage was more of a contract between families decided by the father’s.

I was reminded of the wonderful novel about a friendship between two children in the same village, one of Greek and one of Turkish origin by

I was reminded of the wonderful novel about a friendship between two children in the same village, one of Greek and one of Turkish origin by  French Literature

French Literature Monsieur Pierre Chauveau (Julien’s great grandfather) gave a witness statement on 16 September 1954, describing what he had seen. His unusual testimony was classified by the police as follows:

Monsieur Pierre Chauveau (Julien’s great grandfather) gave a witness statement on 16 September 1954, describing what he had seen. His unusual testimony was classified by the police as follows: The four of them have various interesting encounters, Hubert with a long lost relative whose charred diary he finds in the apartment he left empty for 24 years, Julien meets the original Harry MacElhone, founder of the bar he works in and Magalie seeks out her now thirty-one-year old grandmother Odette.

The four of them have various interesting encounters, Hubert with a long lost relative whose charred diary he finds in the apartment he left empty for 24 years, Julien meets the original Harry MacElhone, founder of the bar he works in and Magalie seeks out her now thirty-one-year old grandmother Odette.

The narrator shares the same name as the author, and though he never knew the exact details of what happened before he was born, except by anecdote, he used fiction to explore and build a narrative that hopefully might have let some of the ghosts he had lived with for many years to rest.

The narrator shares the same name as the author, and though he never knew the exact details of what happened before he was born, except by anecdote, he used fiction to explore and build a narrative that hopefully might have let some of the ghosts he had lived with for many years to rest. A man named Don Henrik is the connection between the stories, and though he is not the centre of any story until the end, through each tale narrated we come to know the hardships he has encountered as he struggled to run his various business ventures, we learn about the equally difficult life path his brother followed, and how that contributed to his father’s financial difficulties. Though it is not focused on in particular, we also know he is a foreigner, we imagine how his may have contributed to the challenges he and his family have encountered.

A man named Don Henrik is the connection between the stories, and though he is not the centre of any story until the end, through each tale narrated we come to know the hardships he has encountered as he struggled to run his various business ventures, we learn about the equally difficult life path his brother followed, and how that contributed to his father’s financial difficulties. Though it is not focused on in particular, we also know he is a foreigner, we imagine how his may have contributed to the challenges he and his family have encountered.

Considered to be one of the most prominent names among the new generation of Guatemalan writers, Rodrigo Fuentes (1984) won the Carátula Central American Short Story Prize (2014) as well as the Juegos Florales of Quetzaltenango Short Story Prize (2008).

Considered to be one of the most prominent names among the new generation of Guatemalan writers, Rodrigo Fuentes (1984) won the Carátula Central American Short Story Prize (2014) as well as the Juegos Florales of Quetzaltenango Short Story Prize (2008). Last year my favourite read

Last year my favourite read

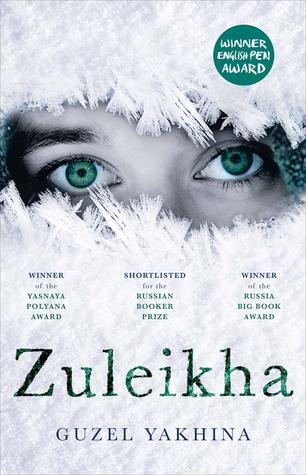

Guzel Yakhina’s grandmother was arrested in the 1930’s, taken by horseback to Kazan and then on a long railway journey (over 2,000 miles) to Siberia. She was exiled from the age of 7 until 17 years, returning to her native village in 1947. It was these formative childhood years that were in a large part responsible for her formidable character.

Guzel Yakhina’s grandmother was arrested in the 1930’s, taken by horseback to Kazan and then on a long railway journey (over 2,000 miles) to Siberia. She was exiled from the age of 7 until 17 years, returning to her native village in 1947. It was these formative childhood years that were in a large part responsible for her formidable character. It seems appropriate to begin this post with a word, since this reading and writing adventure takes place word by word, across time and continents. Our word for today is charco which means puddle in Spanish and is also a colloquialism in some Latin American countries referring to the Atlantic Ocean.

It seems appropriate to begin this post with a word, since this reading and writing adventure takes place word by word, across time and continents. Our word for today is charco which means puddle in Spanish and is also a colloquialism in some Latin American countries referring to the Atlantic Ocean.

Trout, Belly Up

Trout, Belly Up