The International Booker Prize long list was announced today Feb 27. Thirteen novels of translated fiction from 8 languages, 11 countries, six male authors and seven women. The judges this year were looking for distinctive voices that stayed with them, fiction that once you’d read it, you couldn’t stop thinking about.

The prize is awarded every year for a single book that is translated into English and published in the UK or Ireland. It aims to encourage more publishing and reading of quality fiction from all over the world and to promote the work of translators. The contribution of both author and translator is given equal recognition, with the £50,000 prize split between them.

Ted Hodgkinson, Chair of Judges said:

‘What a thrill to share a longlist of such breadth and brilliance, reflecting a cumulative artistry rooted in dialogue between authors and translators, and possessing a power to enlarge the scope of lives encountered on the page, from the epic to the everyday. Whether reimagining foundational myths, envisioning dystopias of disquieting potency, or simply setting the world ablaze with the precision of their perceptions, these are books that left indelible impressions on us as judges. In times that increasingly ask us to take sides, these works of art transcend moral certainties and narrowing identities, restoring a sense of the wonderment at the expansive and ambiguous lot of humanity.’

Below are the novels on the list with a short summary of their premise. Surprisingly, I have read and reviewed two (reviews linked below) and they are indeed thought provoking novels, and I have The Adventures of China Iron on my shelf to read. The shortlist will be announced on April 2nd.

The Enlightenment of The Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar (Iran) Translated by Anonymous from Farsi

The Enlightenment of The Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar (Iran) Translated by Anonymous from Farsi

Set in Iran in the decade following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, this moving, richly imagined novel is narrated by the ghost of Bahar, a 13-year-old girl whose family is compelled to flee their home in Tehran for a new life in a small village, hoping in this way to preserve both their intellectual freedom and their lives. They soon find themselves caught up in the post-revolutionary chaos that sweeps across the country, a madness that affects both living and dead, old and young.

The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree speaks of the power of imagination when confronted with cruelty, and of our human need to make sense of the world through the ritual of storytelling. Through her unforgettable characters and glittering magical realist style, Azar weaves a timely and timeless story that juxtaposes the beauty of an ancient, vibrant culture with the brutality of an oppressive political regime.

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogowa (Japan) Translated by Stephen Snyder from Japanese

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogowa (Japan) Translated by Stephen Snyder from Japanese

Hat, ribbon, bird, rose. To the people on the island, a disappeared thing no longer has any meaning. It can be burned in the garden, thrown in the river or handed over to the Memory Police. Soon enough, the island forgets it ever existed. When a young novelist discovers that her editor is in danger of being taken away by the Memory Police, she desperately wants to save him. For some reason, he doesn’t forget, and it becomes increasingly difficult for him to hide his memories. Who knows what will vanish next?

The Memory Police is a beautiful, haunting and provocative fable about the power of memory and the trauma of loss, from one of Japan’s greatest writers.

The Adventures of China Iron by Gabriela Cabezón Cámara (Argentina)Translated by Iona Macintyre & Fiona Mackintosh from Spanish

The Adventures of China Iron by Gabriela Cabezón Cámara (Argentina)Translated by Iona Macintyre & Fiona Mackintosh from Spanish

1872. The pampas of Argentina. China is a young woman eking out an existence in a remote gaucho encampment. After her no-good husband is conscripted into the army, China bolts

for freedom, setting off on a wagon journey through the pampas in the company of her new-found friend Liz, a settler from Scotland. While Liz provides China with a sentimental education and schools her in the nefarious ways of the British Empire, their eyes are opened to the wonders of Argentina’s richly diverse flora and fauna, cultures and languages, as well as to the ruthless violence involved in nation-building.

This subversive retelling of Argentina’s foundational gaucho epic, Martín Fierro, is a celebration of the colour and movement of the living world, the open road, love and sex, and the dream of lasting freedom. With humour and sophistication, Gabriela Cabezón Cámara has created a joyful, hallucinatory novel that is also an incisive critique of national origin myths and of the casualties of ruthless progress.

Red Dog by Willem Anker (South Africa) Translated by Michiel Heyns from Afrikaans

Red Dog by Willem Anker (South Africa) Translated by Michiel Heyns from Afrikaans

In the 18th century, a giant bestrides the border of the Cape Colony frontier. Coenraad de Buys is a legend, a polygamist, a swindler and a big talker; a rebel who fights with Xhosa chieftains against the Boers and British; the fierce patriarch of a sprawling mixed-race family with a veritable tribe of followers; a savage enemy and a loyal ally. Like the wild dogs who are always at his heels, he roams the shifting landscape of southern Africa, hungry and spoiling for a fight.

Red Dog is a brilliant, fiercely powerful novel – a wild, epic tale of Africa in a time before boundaries between cultures and peoples were fixed.

The Other Name: Septology I – II byJon Fosse (Norway) Translated by Damion Searls from Norwegian

The Other Name: Septology I – II byJon Fosse (Norway) Translated by Damion Searls from Norwegian

Follows the lives of two men living close to each other on the west coast of Norway. The year is coming to a close and Asle, an ageing painter and widower, is reminiscing about his life. He lives alone, his only friends being his neighbour, Åsleik, a bachelor and traditional Norwegian fisherman-farmer, and Beyer, a gallerist who lives in Bjørgvin, a couple hours’ drive south of Dylgja, where he lives. There, in Bjørgvin, is another Asle, also a painter. He and the narrator are doppelgangers – two versions of the same person, two versions of the same life. Written in hypnotic prose that shifts between the first and third person, The Other Name calls into question concrete notions around subjectivity and the self. What makes us who we are? And why do we lead one life and not another? With The Other Name, the first volume in a trilogy of novels, Fosse presents us with an indelible and poignant exploration of the human condition that will endure as his masterpiece.

The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (Georgia) Translated by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin from German

The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (Georgia) Translated by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin from German

At the start of the 20th century, on the edge of the Russian empire, a family prospers. It owes its success to a delicious chocolate recipe, passed down the generations with great solemnity and caution. A caution which is justified: this is a recipe for ecstasy that carries a very bitter aftertaste…

Stasia learns it from her Georgian father and takes it north, following her new husband Simon to his posting at the centre of the Russian Revolution in St Petersburg. But Stasia’s will be the first of a symphony of grand, if all too often doomed, romances that swirl from sweet to sour in this epic tale of the red century.

Tumbling down the years, and across vast expanses of longing and loss, generation after generation of this compelling family hears echoes and sees reflections. Great characters and greater relationships come and go and come again; the world shakes, and shakes some more, and the reader rejoices to have found at last one of those glorious old books in which you can live and learn, be lost and found, and make indelible new friends.

Serotonin by Michel Houellebecq (France) Translated by Shaun Whiteside from French

Serotonin by Michel Houellebecq (France) Translated by Shaun Whiteside from French

Dissatisfied and discontented, Florent-Claude Labrouste feels he is dying of sadness. His young girlfriend hates him and his career as an engineer at the Ministry of Agriculture is pretty much over. His only relief comes in the form of a pill – white, oval, small. Recently released for public consumption, Captorix is a new brand of anti-depressant which works by altering the brain’s release of serotonin.

Armed with this new drug, Labrouste decides to abandon his life in Paris and return to the Normandy countryside where he used to work promoting regional cheeses, and where he had once been in love. But instead of happiness, he finds a rural community devastated by globalisation and European agricultural policies, and local farmers longing, like Labrouste himself, for an impossible return to what they remember as the golden age.

Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann (Austria-Germany) Translated by Ross Benjamin from German

Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann (Austria-Germany) Translated by Ross Benjamin from German

He’s a trickster, a player, a jester. His handshake’s like a pact with the devil, his smile like a crack in the clouds; he’s watching you now and he’s gone when you turn. Tyll Ulenspiegel is here!

In a village like every other village in Germany, a scrawny boy balances on a rope between two trees. He’s practising. He practises by the mill, by the blacksmiths; he practises in the forest at night, where the Cold Woman whispers and goblins roam. When he comes out, he will never be the same. Tyll will escape the ordinary villages. In the mines he will defy death. On the battlefield he will run faster than cannonballs. In the courts he will trick the heads of state. As a travelling entertainer, his journey will take him across the land and into the heart of a never-ending war. A prince’s doomed acceptance of the Bohemian throne has European armies lurching brutally for dominion and now the Winter King casts a sunless pall. Between the quests of fat counts, witch-hunters and scheming queens, Tyll dances his mocking fugue; exposing the folly of kings and the wisdom of fools.

With macabre humour and moving humanity, Daniel Kehlmann lifts this legend from medieval German folklore and enters him on the stage of the Thirty Years’ War. When citizens become the playthings of politics and puppetry, Tyll, in his demonic grace and his thirst for freedom, is the very spirit of rebellion – a cork in water, a laugh in the dark, a hero for all time.

Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor (Mexico) Translated by Sophie Hughes from Spanish

Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor (Mexico) Translated by Sophie Hughes from Spanish

Hurricane Season opens with the macabre discovery of a decomposing body in a small waterway on the outskirts of La Matosa, a village in rural Mexico. It soon becomes apparent that the body is that of the local witch, who is both feared by the men and relied upon by the women, helping them with love charms and illegal abortions.

Mirroring the structure of Gabriel García Márquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold, the novel goes back in time, recounting the events which led to La Matosa’s witch’s murder from several perspectives. Hurricane Season quickly transcends its detective story constraints: the culprits are named early on in the narrative, shifting the question to why rather than who. Through the stories of Luismi, Norma, Brando and Munra, Fernanda Melchor paints a portrait of lives governed by poverty and violence, machismo and misogyny, superstition and prejudice. Written with a brutal lyricism that is as affecting as it is enthralling, Hurricane Season, Melchor’s first novel to appear in English, is a formidable portrait of Mexico and its demons.

Faces on the Tip of My Tongue by Emmanuelle Pagano (France) Translated by Sophie Lewis & Jennifer Higgins from French

Faces on the Tip of My Tongue by Emmanuelle Pagano (France) Translated by Sophie Lewis & Jennifer Higgins from French

Meetings, partings, loves and losses in rural France are dissected with compassion.

The late wedding guest isn’t your cousin but a drunken chancer. The driver who gives you a lift isn’t going anywhere but off the road. Snow settles on your car in summer and the sequins found between the pages of a borrowed novel will make your fortune. Pagano’s stories weave together the mad, the mysterious and the dispossessed of a rural French community with honesty and humour. A superb, cumulative collection from a unique French voice.

Little Eyes by Samanta Schweblin (Argentina) Translated by Megan McDowell from Spanish

Little Eyes by Samanta Schweblin (Argentina) Translated by Megan McDowell from Spanish

They’ve infiltrated homes in Hong Kong, shops in Vancouver, the streets of Sierra Leone, town squares of Oaxaca, schools in Tel Aviv, bedrooms in Indiana.

They’re not pets, nor ghosts, nor robots. They’re real people, but how can a person living in Berlin walk freely through the living room of someone in Sydney? How can someone in Bangkok have breakfast with your children in Buenos Aires, without you knowing? Especially when these people are completely anonymous, unknown, untraceable.

The characters in Samanta Schweblin’s wildly imaginative new novel, Little Eyes, reveal the beauty of connection between far-flung souls – but they also expose the ugly truth of our increasingly linked world. Trusting strangers can lead to unexpected love, playful encounters and marvellous adventures, but what if it can also pave the way for unimaginable terror? Schweblin has created a dark and complex world that is both familiar but also strangely unsettling, because it’s our present and we’re living it – we just don’t know it yet.

The Discomfort of Evening by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld (The Netherlands) Translated by Michele Hutchison from Dutch

The Discomfort of Evening by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld (The Netherlands) Translated by Michele Hutchison from Dutch

Jas lives with her devout farming family in the rural Netherlands. One winter’s day, her older brother joins an ice skating trip. Resentful at being left alone, she makes a perverse plea to God; he never returns. As grief overwhelms the farm, Jas succumbs to a vortex of increasingly disturbing fantasies, watching her family disintegrate into a darkness that threatens to derail them all.

A bestselling sensation in the Netherlands by a prize-winning young poet, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s debut novel lays everything bare. It is a world of language unlike any other, which Michele Hutchison’s striking translation captures in all its wild, violent beauty.

Mac and His Problem by Enrique Vila-Matas (Spain) Translated by Margaret Jull Costa & Sophie Hughes from Spanish

Mac and His Problem by Enrique Vila-Matas (Spain) Translated by Margaret Jull Costa & Sophie Hughes from Spanish

Mac is not writing a novel. He is writing a diary, which no one will ever read. At over 60, and recently unemployed, Mac is a beginner, a novice, an apprentice – delighted by the themes of repetition and falsification, and humbly armed with an encyclopaedic knowledge of literature.

Mac’s wife, Carmen, thinks he is simply wasting his time and in danger of sliding further into depression and idleness. But Mac persists, diligently recording his daily walks through the neighbourhood. It is the hottest summer Barcelona has seen in over a century.

Soon, despite his best intentions (not to write a novel), Mac begins to notice that life is exhibiting strange literary overtones and imitating fragments of plot. As he sizzles in the heatwave, he becomes ever more immersed in literature – a literature haunted by death, but alive with the sheer pleasure of writing.

That’s Ferrante.

That’s Ferrante.

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

Passionate French Women Who Faced Death Unflinchingly

Evangalising Across the Argentinian Countryside

Evangalising Across the Argentinian Countryside

The opening sentence introduces us to the birth of a poverty-stricken community, one that will rise up despite numerous efforts to destroy it. As more displaced people hear of them, it continues to reassemble, grow, and become occupied by the marginalised, who do what they can to get ahead.

The opening sentence introduces us to the birth of a poverty-stricken community, one that will rise up despite numerous efforts to destroy it. As more displaced people hear of them, it continues to reassemble, grow, and become occupied by the marginalised, who do what they can to get ahead.

The more I read, the more this novel got its hooks into me. After a while, a pattern begins to emerge, one that is universal. To find a place where one can live authentically, and be at home.

The more I read, the more this novel got its hooks into me. After a while, a pattern begins to emerge, one that is universal. To find a place where one can live authentically, and be at home.

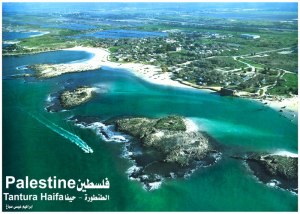

While her mother uses imagination to create a vision of what happened and where the missing are, Ruqayya’s advances then retreats, as the present awakens the past, rarely does she dwell in an idealised future.

While her mother uses imagination to create a vision of what happened and where the missing are, Ruqayya’s advances then retreats, as the present awakens the past, rarely does she dwell in an idealised future. There is no place that quite replaces the childhood environment and home, except perhaps to create one’s own family, and this Raqayya will do, with her son’s and the daughter, a girl Maryam her husband brings home one day from the hospital, adopting her as their own. And in growing things, not the almond tree or the olives, but flowers, a thing of beauty, the damask rose, the bird of paradise.

There is no place that quite replaces the childhood environment and home, except perhaps to create one’s own family, and this Raqayya will do, with her son’s and the daughter, a girl Maryam her husband brings home one day from the hospital, adopting her as their own. And in growing things, not the almond tree or the olives, but flowers, a thing of beauty, the damask rose, the bird of paradise. Drawing inspiration from other texts that have in turn been inspired by a life, or experience lived in Argentina, whether the epic poem ‘the gaucho’ Martin Fierro by José Hernández (a lament for a disappearing way of life) or the autobiography Far Away & Long Ago of the naturalist William Henry Hudson, The Adventures of China Iron is a beautiful elegy (for there will be consolation), a brilliant feat of the imagination that takes readers on an alternative journey.

Drawing inspiration from other texts that have in turn been inspired by a life, or experience lived in Argentina, whether the epic poem ‘the gaucho’ Martin Fierro by José Hernández (a lament for a disappearing way of life) or the autobiography Far Away & Long Ago of the naturalist William Henry Hudson, The Adventures of China Iron is a beautiful elegy (for there will be consolation), a brilliant feat of the imagination that takes readers on an alternative journey.

Translated Fiction

Translated Fiction

5.

5.

What a perfect way to navigate through 500 years of history of a country, without ever getting bogged down in the detail, to follow the lives of daughters, a matrilineal lineage, whose patterns are affected if not dictated by the context of the era within which they’ve lived.

What a perfect way to navigate through 500 years of history of a country, without ever getting bogged down in the detail, to follow the lives of daughters, a matrilineal lineage, whose patterns are affected if not dictated by the context of the era within which they’ve lived. I absolutely loved it, I read this because I seek out works by women in translation to read in August for #WITMonth and finding a book like this is such a joy, for it gives so much in its reading, great storytelling, a potted history of Brazil, a unique multiple women’s perspective and an introduction to an award winning author, the writer of ten novels, this her first translated into English.

I absolutely loved it, I read this because I seek out works by women in translation to read in August for #WITMonth and finding a book like this is such a joy, for it gives so much in its reading, great storytelling, a potted history of Brazil, a unique multiple women’s perspective and an introduction to an award winning author, the writer of ten novels, this her first translated into English. Celestial Bodies won the

Celestial Bodies won the

The Adventures of China Iron by Gabriela Cabezón Cámara (Argentina)Translated by Iona Macintyre & Fiona Mackintosh from Spanish

The Adventures of China Iron by Gabriela Cabezón Cámara (Argentina)Translated by Iona Macintyre & Fiona Mackintosh from Spanish Red Dog by Willem Anker (South Africa) Translated by Michiel Heyns from Afrikaans

Red Dog by Willem Anker (South Africa) Translated by Michiel Heyns from Afrikaans The Other Name: Septology I – II byJon Fosse (Norway) Translated by Damion Searls from Norwegian

The Other Name: Septology I – II byJon Fosse (Norway) Translated by Damion Searls from Norwegian The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (Georgia) Translated by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin from German

The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (Georgia) Translated by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin from German Serotonin by Michel Houellebecq (France) Translated by Shaun Whiteside from French

Serotonin by Michel Houellebecq (France) Translated by Shaun Whiteside from French Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann (Austria-Germany) Translated by Ross Benjamin from German

Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann (Austria-Germany) Translated by Ross Benjamin from German Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor (Mexico) Translated by Sophie Hughes from Spanish

Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor (Mexico) Translated by Sophie Hughes from Spanish Faces on the Tip of My Tongue by Emmanuelle Pagano (France) Translated by Sophie Lewis & Jennifer Higgins from French

Faces on the Tip of My Tongue by Emmanuelle Pagano (France) Translated by Sophie Lewis & Jennifer Higgins from French Little Eyes by Samanta Schweblin (Argentina) Translated by Megan McDowell from Spanish

Little Eyes by Samanta Schweblin (Argentina) Translated by Megan McDowell from Spanish The Discomfort of Evening by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld (The Netherlands) Translated by Michele Hutchison from Dutch

The Discomfort of Evening by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld (The Netherlands) Translated by Michele Hutchison from Dutch Mac and His Problem by Enrique Vila-Matas (Spain) Translated by Margaret Jull Costa & Sophie Hughes from Spanish

Mac and His Problem by Enrique Vila-Matas (Spain) Translated by Margaret Jull Costa & Sophie Hughes from Spanish