I read this for two reasons, one I’ve been wanting to read Ann Petry for a while, The Street and The Narrows were republished in 2020, so I’m looking forward to reading them, but the main reason I chose this title is because I’m an avid reader of Maryse Condé, who wrote I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem. One of her inspirations was this book written for young people by Ann Petry, which predates her novel by 30 years, so it made sense for me to read this one first.

For her the story of Tituba was a story of courage in the face of adversity. It was a lesson of hope and dynamism.

Witch Trials of Salem, History

The witch trials of Salem began in March 1692 with the arrests of Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and the black slave, Tituba, based on forced confessions. The trials were started after people had been accused of witchcraft, primarily by teenage girls, though traced to adult concerns and adult grievances. Quarrels and disputes with neighbors often incited witchcraft allegations.

The witch trials of Salem began in March 1692 with the arrests of Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and the black slave, Tituba, based on forced confessions. The trials were started after people had been accused of witchcraft, primarily by teenage girls, though traced to adult concerns and adult grievances. Quarrels and disputes with neighbors often incited witchcraft allegations.

Women who did not conform to the norms of Puritan society were more likely to be the target of an accusation, especially those who were unmarried or did not have children.

It marked the beginning of a period of paranoia in which nineteen women and one man were hanged, before the governor of the colony sent a report to London about the cases of 50 women and a general pardon was granted, putting an end to a disturbing chapter in the history of the village, subsequently renamed Danvers.

Though Tituba was acquitted, prisoners were required to pay the cost of their stay in prison, including the cost of chains and shackles. She was eventually sold for the price of those fees, though it is not known to whom. Ann Petry shares her theories, which we discover here, and Maryse Condé has another.

It is one of Colonial America’s most notorious cases of mass hysteria, a cautionary tale about the dangers of isolationism, religious extremism, false accusations, fake news and lapses in due process.

Review

I had read nothing about the witch trials before, though I’d heard of them, but I’m glad that this was my introduction, to see this little segment of American history, through the eyes of the innocent black slave, Tituba and her husband John.

I had read nothing about the witch trials before, though I’d heard of them, but I’m glad that this was my introduction, to see this little segment of American history, through the eyes of the innocent black slave, Tituba and her husband John.

As the book opens and Tituba and John are in the kitchen of the Barbados home they live in, the scene is so evocative, you can’t imagine how their lives are going to change so abruptly, having been so stable for so long – but then the harsh reality of them being commodities, slaves, sold like jewels, to pay a debt, their lives irrevocably changed, within 24 hours they are on a ship heading for the Bay Colony of Boston, their new owner the Reverend Parris.

Her husband instills in her the importance of staying alive and maintaining good health.

“Remember, always remember, the slave must survive. No matter what happens to the master, the slave must survive.”

Petry’s descriptions of the environment are so evocative, the contrast so great, from the warmth of the island to the damp, unwelcoming cold climate of Massachusetts.

Tituba is caring and empathetic, she has a traditional knowledge of herbs from the island, learned from the women in her family, in Boston she searches in the woods for substitutes and is helped by another woman with knowledge of herbal medicine. She is sensitive to people, animals and the environment.

Photo by Plato Terentev on Pexels.com

Sometimes if she stood still, used all her senses, sight and sound and touch and small would make a place speak to her. She closed her eyes and took a deep breath.

She decided it was not an evil house. It was sad and gloomy. Nothing about it suggested happiness in the future. It had been a long time since anyone had been happy in this house. People leave something of themselves in a house, and the spirit of this house was frighteningly sad.

However, these people live in fearful times and among people whose belief system instills fear and suspicion. They bear children whose imaginations run wild, their behaviour’s running even wilder.

She finally accepted the fact that Abigail was her enemy, and though young, a dangerous enemy. On the other hand, Samuel Conkin, the weaver, was her friend, and though a new friend, a very good friend.

Photo by Susanne Jutzeler on Pexels.com

Tituba is a wonderful character, depicted with compassion and understanding, put in a situation where young people are drawn towards her but unable to overcome their own inner hurts, exaggerate and invent scenarios, combining imagination and superstition, creating drama that spirals out of control into very real consequences for those accused of “witching”, until the farce that it is, becomes all too clear, though not without lives having been lost.

Elena Ferrante in The Lying Life of Adults shows that sometime erratic behaviour of an adolescent and its consequences. Ann Petry shows how childish games, immaturity, attention seeking and hurt can claim lives, and though her book offers a message of courage in the face of adversity, it also offers a warning to that same youthful audience, that lives can be irrevocably damaged by the actions of a few.

I loved the character Petry created, her many talents and her resilience and the imagined appreciation that did exist, even if that might have been willful fantasy, knowing that in the era in which she lived, it was rare indeed for any person who purchased a slave to treat them as her weaver did.

Petry offers perhaps the most persuasive explanation of all—that cruelty begets cruelty, among children as well as adults. At least half the novel takes place before the trials, building the case for the horrors that follow. Anna Mae Duane, The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, Johns Hopkins University Press

Highly Recommended.

Further Reading

Article, Smithsonian Magazine: Unraveling the Many Mysteries of Tituba, the Star Witness of the Salem Witch Trials by Stacy Schiff; Nov 2015

Play: The Crucible (1952), by Arthur Miller

Essay: Ann Petry

Story of the Week: Harlem Ann Petry (1908-1997)

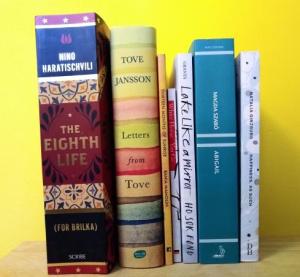

Seven titles were shortlisted for the annual Women in Translation award from 132 eligible entries, 16 titles made the initial longlist:

Seven titles were shortlisted for the annual Women in Translation award from 132 eligible entries, 16 titles made the initial longlist: Abigail by Magda Szabó (Hungary), translated by Len Rix (MacLehose Press, 2020)

Abigail by Magda Szabó (Hungary), translated by Len Rix (MacLehose Press, 2020) Happiness, As Such by Natalia Ginzburg (Italy) translated by Minna Zallmann Proctor (Daunt Books Publishing, 2019)

Happiness, As Such by Natalia Ginzburg (Italy) translated by Minna Zallmann Proctor (Daunt Books Publishing, 2019) Lake Like a Mirror by Ho Sok Fong (Malaysia) translated from Chinese by Natascha Bruce (Granta Publications, 2019)

Lake Like a Mirror by Ho Sok Fong (Malaysia) translated from Chinese by Natascha Bruce (Granta Publications, 2019) Letters from Tove by Tove Jansson (Finland) edited by Boel Westin & Helen Svensson, translated from Swedish by Sarah Death (Sort of Books, 2019)

Letters from Tove by Tove Jansson (Finland) edited by Boel Westin & Helen Svensson, translated from Swedish by Sarah Death (Sort of Books, 2019) The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (Georgia/Germany), translated from German by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin (Scribe UK, 2019)

The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (Georgia/Germany), translated from German by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin (Scribe UK, 2019) Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun (Sudan), translated from Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette (Comma Press, 2019)

Thirteen Months of Sunrise by Rania Mamoun (Sudan), translated from Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette (Comma Press, 2019) White Horse by Yan Ge (China), translated from Chinese by Nicky Harman (HopeRoad, 2019)

White Horse by Yan Ge (China), translated from Chinese by Nicky Harman (HopeRoad, 2019) Isabella (Smokestack Books, 2019), a collection of fiercely feminist poems by the Italian Renaissance writer Isabella Morra translated by Caroline Maldonado

Isabella (Smokestack Books, 2019), a collection of fiercely feminist poems by the Italian Renaissance writer Isabella Morra translated by Caroline Maldonado the extraordinary memoir about mushrooms and grief, The Way Through the Woods (Scribe UK, 2019) by Malaysian-born Long Litt Woon, translated from Norwegian by Barbara Haveland

the extraordinary memoir about mushrooms and grief, The Way Through the Woods (Scribe UK, 2019) by Malaysian-born Long Litt Woon, translated from Norwegian by Barbara Haveland and the pacey young adult thriller set in a small French town rife with racism and rage Summer of Reckoning (Bitter Lemon Press, 2020) by Marion Brunet, translated from French by Katherine Gregor.

and the pacey young adult thriller set in a small French town rife with racism and rage Summer of Reckoning (Bitter Lemon Press, 2020) by Marion Brunet, translated from French by Katherine Gregor.

From the opening pages, as Giovanna overhears a random comment from her father, it expands in her mind and overtakes her physically and mentally like a disease, affecting her mind, causing her to act in certain ways.

From the opening pages, as Giovanna overhears a random comment from her father, it expands in her mind and overtakes her physically and mentally like a disease, affecting her mind, causing her to act in certain ways.

As I’m currently reading her most recent novel,

As I’m currently reading her most recent novel,  I’ve also added the countries the author is associated with, either by birth and/or nationality, as I find that helpful, it being one of the criteria by which I decide whether to read a book or not – to avoid always reading works from the same cultural influence.

I’ve also added the countries the author is associated with, either by birth and/or nationality, as I find that helpful, it being one of the criteria by which I decide whether to read a book or not – to avoid always reading works from the same cultural influence.

It was inspired by some of his own personal experience, his mother died of alcoholism when he was 16.

It was inspired by some of his own personal experience, his mother died of alcoholism when he was 16.

Handiwork is a pure joy to read, it’s a small book, with often only a paragraph on a page, it has a beautifully thought out structure, referencing a number of different texts that the author, who is an artist, a craftswoman clearly holds dear and memories of her father and grandfather, as family members who worked with their hands.

Handiwork is a pure joy to read, it’s a small book, with often only a paragraph on a page, it has a beautifully thought out structure, referencing a number of different texts that the author, who is an artist, a craftswoman clearly holds dear and memories of her father and grandfather, as family members who worked with their hands.

Anne Heffron tells us it took her 93 days to write her book, but really it took a lifetime and she is to be commended for being able to complete it.

Anne Heffron tells us it took her 93 days to write her book, but really it took a lifetime and she is to be commended for being able to complete it.

I read Hadji Murad because it was referenced in the last pages of Leila Aboulela’s excellent

I read Hadji Murad because it was referenced in the last pages of Leila Aboulela’s excellent

I was completely drawn into the dual narrative story and loved both parts of it, modern day Scotland and mid 1800’s Russia and the Caucasus.

I was completely drawn into the dual narrative story and loved both parts of it, modern day Scotland and mid 1800’s Russia and the Caucasus.