Marlon James novel A Brief History of Seven Killings was the winner of the Man Booker Prize in 2015, a year that saw an exceptionally diverse array of novels long listed.

Marlon James novel A Brief History of Seven Killings was the winner of the Man Booker Prize in 2015, a year that saw an exceptionally diverse array of novels long listed.

As a reminder, since it was nearly a year ago that this book won the prize, this was what Michael Wood, Chair of the judges, had to say about it:

‘This book is startling in its range of voices and registers, running from the patois of the street posse to The Book of Revelation. It is a representation of political times and places, from the CIA intervention in Jamaica to the early years of crack gangs in New York and Miami.

‘It is a crime novel that moves beyond the world of crime and takes us deep into a recent history we know far too little about. It moves at a terrific pace and will come to be seen as a classic of our times.’

It is a novel that was hailed as being exceptional in itself, much of it written in that Jamaican patois mentioned, via a litany of voices from the ganglands of the Jamaican ghetto.

I admit that it wasn’t exactly on my reading list, with its promise of violence, killing, drug related activities and dozens of characters, however the book was gifted to me by a visiting Professor, who had little to say about it, but was keen to know my thoughts. So I made it my #OneSummerChunkster and jumped right in, mind wide open.

It is difficult and almost seems inappropriate to rate this novel (I gave it 5 stars on Goodreads.com) in terms of appeal, as it is an incredibly written and unique work, with a huge amount of research that went into the writing and authenticity of its creation.

I can’t say I loved it, it was a tough read in places and definitely not the kind of book I would normally choose nor the kind of film/TV series I would watch, but it is an awe-inspiring creation and for that I agree, it is indeed an amazing oeuvre and warrants the 5 stars, though as far as favourite books go or works I’d recommend, I hesitate and would say its not an experience I would choose to repeat often.

I can’t say I loved it, it was a tough read in places and definitely not the kind of book I would normally choose nor the kind of film/TV series I would watch, but it is an awe-inspiring creation and for that I agree, it is indeed an amazing oeuvre and warrants the 5 stars, though as far as favourite books go or works I’d recommend, I hesitate and would say its not an experience I would choose to repeat often.

I was grateful for the list of characters up front, which I referred to often at the beginning of each chapter, as we are plunged straight into the multi-character narrative with its discordant musical tones, slice of life in the ghetto, the Singer (never referred to by name) not present, though always there in the greater awareness of them all. Life has little meaning and killing a mere rise above assault.

It must have been incredible to listen to the audio version as the individual character voices are so unique, it is the literary equivalent of reading a musical score for a symphony like you’ve never heard before, I am in awe that Marlon James succeeded in creating such a work, that balances so many threads of narrative, so many characters, the timeline, the Jamaican patois, the gangspeak, the violence, the framing of the story around the assassination attempt of that “Singer” who is never named, assumed to be Bob Marley. As Eileen Battersby, reviewer of The Irish Times put it so eloquently:

Reading Marlon’s prose is akin to injecting liquid fire into your brain.

It paints a dark, dangerous picture of ghetto life and the activities, interactions of drug dealers and their crews and the fear by those who are in any way touched or implicated in their actions. In a schizophrenic stream of consciousness narrative, gang members live their days in altered states of consciousness, paranoid, high, wanting to kill – in a frantic, dangerous other worldly horror.

Flicking between the narratives of CIA members, a young woman afraid of what she has witnessed, a journalist, all present leading up to the attempted shooting of the Singer. Surreal. It made me wonder at times if the author was in an altered state of consciousness while writing – it is some kind of trip!

I did have to push myself in parts to keep going, it’s brutal at times, and upon reaching halfway, I took the afternoon off to read The Rabbit House by Laura Alcoba. But then the pace picked up again as Papa-Lo the don, and top members of a rival gang were about to be chucked into jail together in the hope they’d self destruct. James’s lulls never last and we are pulled back into the riveting storyline, following our favourites and steeling ourselves against spending time the company of those we know are going to detest.

I was left admiring the creation even if it wasn’t always a particularly enjoyable ride and as my comment made to another reader below shows, the beach was actually a great place to read it!

I was left admiring the creation even if it wasn’t always a particularly enjoyable ride and as my comment made to another reader below shows, the beach was actually a great place to read it!

I feel like I’m reading a Jamaican symphony, a cacophony of words and sounds and emotions, not sure if it was the heat of the sun or the power of the book, but I had to keep putting it down to take a plunge into the cool ocean!

That said, I am intrigued and do intend to read Marlon James’s The Book of Night Women wondering how he handles a story with female characters.

On the day when the nation is shocked and grieving after a devastating earthquake, that has destroyed entire villages and resulted in a significant loss of life, I don’t know how appropriate it is to share their literature, perhaps in the case of this particular novel, it serves to put things in perspective.

On the day when the nation is shocked and grieving after a devastating earthquake, that has destroyed entire villages and resulted in a significant loss of life, I don’t know how appropriate it is to share their literature, perhaps in the case of this particular novel, it serves to put things in perspective. A national bestseller for almost an entire year, The Days of Abandonment shocked and captivated its Italian public when first published.

A national bestseller for almost an entire year, The Days of Abandonment shocked and captivated its Italian public when first published.

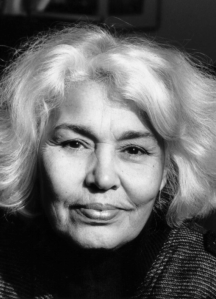

From her early days, Firdaus was a child who was noticed, though rarely looked out for, instances of cruelty and neglect made up the patchwork of her childhood. “Rescued” by an Uncle who’d already crossed filial boundaries, her one respite was to have been sent by him to school, his new wife further insisting she live there, perhaps the only paradisiacal period of her life, the one time she was left alone to flourish, to evolve, gaining her secondary school certificate, her sole prized possession.

From her early days, Firdaus was a child who was noticed, though rarely looked out for, instances of cruelty and neglect made up the patchwork of her childhood. “Rescued” by an Uncle who’d already crossed filial boundaries, her one respite was to have been sent by him to school, his new wife further insisting she live there, perhaps the only paradisiacal period of her life, the one time she was left alone to flourish, to evolve, gaining her secondary school certificate, her sole prized possession. Selected in 2010 as one of The Best of Young Spanish Language Novelists by

Selected in 2010 as one of The Best of Young Spanish Language Novelists by

Rachel Cooke in this Guardian article

Rachel Cooke in this Guardian article

It should have been perfect, but things change when an old friend of her mother’s Anne arrives and she and her father announce their intention to marry. Although it is actually something Cecile feels is right for them and she adores Anne, part of her resents what signifies to her the end to the playful era she and her father have indulged, for Anne’s presence in their lives will certainly bring order and sensibility.

It should have been perfect, but things change when an old friend of her mother’s Anne arrives and she and her father announce their intention to marry. Although it is actually something Cecile feels is right for them and she adores Anne, part of her resents what signifies to her the end to the playful era she and her father have indulged, for Anne’s presence in their lives will certainly bring order and sensibility. It is 1947, in the province of Punjab, which sits between India and Pakistan, an area where Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and others live side by side. Tension is mounting as political events cause rifts between friends and neighbours as many of the Muslim population support the area becoming part of Pakistan and many Hindu fear for their lives, while the same tensions exist among Muslims living in the predominantly Hindu parts of India.

It is 1947, in the province of Punjab, which sits between India and Pakistan, an area where Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and others live side by side. Tension is mounting as political events cause rifts between friends and neighbours as many of the Muslim population support the area becoming part of Pakistan and many Hindu fear for their lives, while the same tensions exist among Muslims living in the predominantly Hindu parts of India. The thing they all fear most, that some desire most happens and Asha’s family leave their past behind and head for Delhi. Firoze helps them to escape and Asha leaves with a secret she has kept from everyone, the future unknown.

The thing they all fear most, that some desire most happens and Asha’s family leave their past behind and head for Delhi. Firoze helps them to escape and Asha leaves with a secret she has kept from everyone, the future unknown.

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche.

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche. It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese.

It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese. Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors.

Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors. Absolutely brilliant, astonishing, loved it, one of my Top Reads of 2016 for sure.

Absolutely brilliant, astonishing, loved it, one of my Top Reads of 2016 for sure.

The novel is predominantly a second person narrative addressed to Elijah, long after she has lost him, narrating the events of their meeting, her pursuit of the dinosaur fossils straight after meeting him, her return to Dhaka and then her escape from her family to Chittagong, to work alongside a female film-maker interviewing workers on the ship graveyards, beaches where enormous liners are dismantled and parts recycled.

The novel is predominantly a second person narrative addressed to Elijah, long after she has lost him, narrating the events of their meeting, her pursuit of the dinosaur fossils straight after meeting him, her return to Dhaka and then her escape from her family to Chittagong, to work alongside a female film-maker interviewing workers on the ship graveyards, beaches where enormous liners are dismantled and parts recycled.