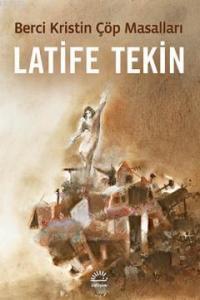

translated by Ruth Christie, Saliha Paker

“One winter night, on a hill where the huge refuse bins came daily and dumped the city’s waste, eight shelters were set up by lantern-light near the garbage heaps.”

The opening sentence introduces us to the birth of a poverty-stricken community, one that will rise up despite numerous efforts to destroy it. As more displaced people hear of them, it continues to reassemble, grow, and become occupied by the marginalised, who do what they can to get ahead.

The opening sentence introduces us to the birth of a poverty-stricken community, one that will rise up despite numerous efforts to destroy it. As more displaced people hear of them, it continues to reassemble, grow, and become occupied by the marginalised, who do what they can to get ahead.

Mattresses were unrolled and kilim-rugs spread on the earthen floors. The damp walls were hung with faded pictures and brushes with their blue bead good-luck charms, cradles were slung from the roofs and a chimney pipe was knocked through the sidewall of every hut.

It’s a story of impoverishment, perseverance and the survival of the poorest. Every step forward encounters a knock back, an obstacle to overcome. Toxic factories employ them, their ailments dealt with in bribes, even their love lives are dictated by the relative positions they occupy in the unconventional heirarchy of the community.

The workers named the factories after their effects, some made the lungs collapse, some shrivelled the eye, some caused deafness, some made a woman barren. Their proverb for marriage between equals was ‘A bride with dust in her lungs to the brave lad with lead in his blood.’ The saying gained ground when one after another the young car battery workers married girls from the linen factory.

After winning the battle of constant demolition and renaming it ‘Battle Hill’, two official looking men replace their sign with a blue plaque inscribed ‘Flower Hill’.

After the renaming, people heard the demolition had stopped and came to the Hill in their hundreds, deceived by the charm of its name.

Rumour and gossip fuel their perceptions and without worldly knowledge they speculate; theories on events pass from one person to another, changing and evolving into a level of understanding they can accept.

One night yellow pamphlets are stealthily left at their doors, by morning they are strewn everywhere, caught in branches, stuck under their doors. They couldn’t understand why the workers would leave them and others wondered why they could not speak up instead of writing and why they’d left them in the dead of night.

Flower Hill Folk!

Support the strike!

Individuals rise and fall in power, characters referred to by occupation or memorable anecdote, new creatures arrive like ‘The Regular Worker’ spawning the song ‘Work Faster’ and ‘Poet Teacher’ writes about scavenger birds and his pupils.

Author, Latife Tekin

A lyrical voice is given of a metaphorical nature to the deprived, who have memories of villages of old, of fleeing, of different times. Latife Tekin “gives expression not only to their way of life but also to their outlook on life, perception of reality, sense of humour and dreams.”

It is told in such an engaging style, it reads as if it is narrated aloud, though it is neither fairy tale nor fantasy, it is quite unlike anything I’ve read before, the story and the voice, a depiction of the creation and development of an aspiring community of marginalised people.

Assuming the position of a detached but devoted narrator rather than a patronising intellectual onlooker, Tekin has reconstructed the dreams and realities of sqatterland in specific detail and with a uniquely metaphoric use of the language, without overlooking the humorous attitudes, ironic perception and emotional vitality of the community amid the filth and poverty of its living conditions. Saliha Paker, Introduction

Further Reading

Article: Contemporary Turkish Women Writers in English Translation by Dr. Roberta Micallef

Review: Bosphorous Review of Books reviews Berji Kristen by Luke Frostick

My Reviews of Books by Turkish Women Authors

The Other Side of the Mountain by Erendiz Atasü tr. Elizabeth Maslen

Three Daughters of Eve by Elif Shafak

Honour by Elif Shafak

The Happiness of Blonde People by Ekif Shafak

The Gold Letter is a story of Greek families living in what was then known as Constantinople (later renamed as Istanbul, one of many name changes – The city was founded in 667 BC and named Byzantium by the Greeks ), and how the same twist of fate affects three generations of the same two families, where a young woman and a young man fall in love, only to have the union thwarted by their parents – in each generation it is for a different reason, beginning with them not being of the same wealth and social status, where marriage was more of a contract between families decided by the father’s.

The Gold Letter is a story of Greek families living in what was then known as Constantinople (later renamed as Istanbul, one of many name changes – The city was founded in 667 BC and named Byzantium by the Greeks ), and how the same twist of fate affects three generations of the same two families, where a young woman and a young man fall in love, only to have the union thwarted by their parents – in each generation it is for a different reason, beginning with them not being of the same wealth and social status, where marriage was more of a contract between families decided by the father’s.

I was reminded of the wonderful novel about a friendship between two children in the same village, one of Greek and one of Turkish origin by

I was reminded of the wonderful novel about a friendship between two children in the same village, one of Greek and one of Turkish origin by  I’m glad The Open Door was brought back into publication, it was a landmark work in woman’s writing in Arabic when it was first published in 1960, an important commentary on the challenges women and girls in so many societies face, a consequence of patriarchy; an effect that is being busted wide open today, forcing transparency, offering support, healing and with hope, gradual change in many countries today. It seems timely to revisit this, or to read it for the first time, as will likely be the case for many.

I’m glad The Open Door was brought back into publication, it was a landmark work in woman’s writing in Arabic when it was first published in 1960, an important commentary on the challenges women and girls in so many societies face, a consequence of patriarchy; an effect that is being busted wide open today, forcing transparency, offering support, healing and with hope, gradual change in many countries today. It seems timely to revisit this, or to read it for the first time, as will likely be the case for many.

About her novel, she had this to say:

About her novel, she had this to say:

The narrating of family stories, taking us back as far as her great-grandfather Montazemolmolk with his harem of 52 wives, serves to provide context and an explanation for why certain family members might have behaved or lived in the way they did, helping us understand their motives and actions.

The narrating of family stories, taking us back as far as her great-grandfather Montazemolmolk with his harem of 52 wives, serves to provide context and an explanation for why certain family members might have behaved or lived in the way they did, helping us understand their motives and actions.

I was intrigued to read a book by a Mauritian author during Women in Translation month. Eve out of her Ruins hadn’t been on my initial list, but it was recommended to me and I decided to get a copy especially as I’ve been seeing many images of the island of Mauritius recently.

I was intrigued to read a book by a Mauritian author during Women in Translation month. Eve out of her Ruins hadn’t been on my initial list, but it was recommended to me and I decided to get a copy especially as I’ve been seeing many images of the island of Mauritius recently.

Nothing Holds Back the Night is the book Delphine de Vigan avoided writing until she could no longer resist its call. It is a book about her mother Lucile, who she introduces to us on the first page as she enters her apartment and discovers her sleeping, the long, cold, hard sleep of death. Her mother was 61-years-old.

Nothing Holds Back the Night is the book Delphine de Vigan avoided writing until she could no longer resist its call. It is a book about her mother Lucile, who she introduces to us on the first page as she enters her apartment and discovers her sleeping, the long, cold, hard sleep of death. Her mother was 61-years-old. I read this book in a day, it’s one of those narratives that once you start you want to continue reading, it’s described as autofiction, a kind of autobiography and fiction, though there is little doubt it is the story of the author’s mother, as she constructs thoughts and dialogue inspired by the information provided by family members, acknowledging that for many of the events, some often have a different memory which she even shares.

I read this book in a day, it’s one of those narratives that once you start you want to continue reading, it’s described as autofiction, a kind of autobiography and fiction, though there is little doubt it is the story of the author’s mother, as she constructs thoughts and dialogue inspired by the information provided by family members, acknowledging that for many of the events, some often have a different memory which she even shares. The Complete Claudine by Colette tr. Antonia White (French) – Colette began her writing career with Claudine at School, which catapulted the young author into instant, sensational success. Among the most autobiographical of Colette’s works, these four novels are dominated by the child-woman Claudine, whose strength, humour, and zest for living make her a symbol for the life force.

The Complete Claudine by Colette tr. Antonia White (French) – Colette began her writing career with Claudine at School, which catapulted the young author into instant, sensational success. Among the most autobiographical of Colette’s works, these four novels are dominated by the child-woman Claudine, whose strength, humour, and zest for living make her a symbol for the life force.

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche.

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche. It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese.

It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese. Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors.

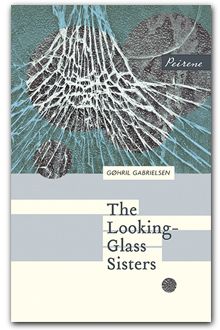

Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors. Two sisters have lived in the same house all their lives, their parents long gone and they can barely tolerate each other. They are bound together in one sense due to the practical disability of the younger sister, but also through the inherent sense of duty and responsibility of the first-born.

Two sisters have lived in the same house all their lives, their parents long gone and they can barely tolerate each other. They are bound together in one sense due to the practical disability of the younger sister, but also through the inherent sense of duty and responsibility of the first-born.

The Door is an overwrought, neurotic narrative by “the lady writer”, (possibly Szabó’s alter-ego, as there are similarities) describing her 20 year relationship with Emerence, the older lady who interviews her prospective employer to see if she’ll consider accepting the cleaning job on offer.

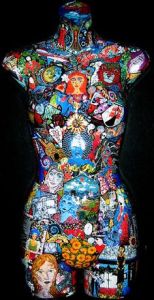

The Door is an overwrought, neurotic narrative by “the lady writer”, (possibly Szabó’s alter-ego, as there are similarities) describing her 20 year relationship with Emerence, the older lady who interviews her prospective employer to see if she’ll consider accepting the cleaning job on offer. Later, only very much later, in one of the most surreal moments I have ever experienced, I wandered amidst the ruin of Emerence’s life, and discovered, there in her garden, standing on the lawn, the faceless dressmaker’s dummy designed for my mother’s exquisite figure. Just before they sprinkled it with petrol and set fire to it, I caught sight of Emerence’s ikonstasis. We were all there, pinned to the fabric over the dolls’ ribcage: the Grossman family, my husband, Viola, the Lieutenant Colonel, the nephew, the baker, the lawyer’s son, and herself, the young Emerence, with radiant golden hair, in her maid’s uniform and little crested cap, holding a baby in her arms.

Later, only very much later, in one of the most surreal moments I have ever experienced, I wandered amidst the ruin of Emerence’s life, and discovered, there in her garden, standing on the lawn, the faceless dressmaker’s dummy designed for my mother’s exquisite figure. Just before they sprinkled it with petrol and set fire to it, I caught sight of Emerence’s ikonstasis. We were all there, pinned to the fabric over the dolls’ ribcage: the Grossman family, my husband, Viola, the Lieutenant Colonel, the nephew, the baker, the lawyer’s son, and herself, the young Emerence, with radiant golden hair, in her maid’s uniform and little crested cap, holding a baby in her arms. Magda Szabó was born in 1917 in Debrecen, Hungary, her father a member of the City Council, and her mother a teacher.

Magda Szabó was born in 1917 in Debrecen, Hungary, her father a member of the City Council, and her mother a teacher.