Dear Husband,

I lost our children today.

What an opening line. Tahmima Anam’s A Golden Age plunges you right into the twin events that form the basis of Rehana’s character as a parent, fiercely protective and determined to have them near her.

Dear Husband,

Our children are no longer our children.

The death of her husband and her fight to keep her children, when her dead husband’s brother and his childless wife claim they could take better care of them.

The first chapter begins with that day in 1959 when the court gives custody to her brother and sister-in-law, who live in Lahore, (West Pakistan) over 1000 miles and an expensive flight away from Dhaka (East Pakistan).

The novel then jumps forward and is set in 1971, in Dhaka, the year of its war of independence, when East separated from West Pakistan and became Bangladesh (when you look at the area on a map, they are geographically separate, with no common border, India lies between them).

In 1971, Rehana’s children, Maya and Sohail are university students and back living with their mother after she discovered a way of becoming financially independent without having to remarry. Despite her efforts to protect them, she is unable to stop them becoming involved in the events of the revolution, her son joining a guerrilla group of freedom fighters and her daughter leaving for Calcutta to write press releases and work in nearby refugee camps.

He’ll never make a good husband, she heard Mrs Chowdhury say. Too much politics.

The comment had stung because it was probably true. Lately the children had little time for anything but the struggle. It had started when Sohail entered the university. Ever since ’48, the Pakistani authorities had ruled the eastern wing of the country like a colony. First they tried to force everyone to speak Urdu instead of Bengali. They took the jute money from Bengal and spent it on factories in Karachi and Islamabad. One general after another made promises they had no intention of keeping. The Dhaka university students had been involved in the protests from the very beginning, so it was no surprise Sohail had got caught up, Maya too. Even Rehana could see the logic: what sense did it make to have a country in two halves, posed on either side of India like a pair of horns?

Rather than lose her children again, Rehana supports them and their cause, finding herself on the opposite side of a conflict to her disapproving family who live in West Pakistan.

As she recited the pickle recipe to herself, Rehana wondered what her sisters would make of her at this very moment. Guerillas at Shona. Sewing kathas on the rooftop. Her daughter at rifle practice. The thought of their shocked faces made her want to laugh.She imagined the letter she would write. Dear sisters, she would say. Our countries are at war; yours and mine. We are on different sides now. I am making pickles for the war effort. You see how much I belong here and not to you.

Anam follows the lives of one family and their close neighbours, illustrating how the historical events of that year affected people and changed them. It is loosely based on a similar story told to the author by her grandmother who had been a young widow for ten years already, when the war arrived.

When I first sat down to write A Golden Age, I imagined a war novel on an epic scale. I imagined battle scenes, political rallies, and the grand sweep of history. But after having interviewed more than a hundred survivors of the Bangladesh War for Independence, I realised it was the very small details that always stayed in my mind- the guerilla fighters who exchanged shirts before they went into battle, the women who sewed their best silk saris into blankets for the refugees. I realised I wanted to write a novel about how ordinary people are transformed by war, and once I discovered this, I turned to the story of my maternal grandmother, Mushela Islam, and how she became a revolutionary.

It’s a fabulous and compelling novel of a family disrupted by war, thrown into the dangers of standing up for what they believe is right, influenced by love, betrayed by jealousies and of a young generation’s desire to be part of the establishment of independence for the country they love.

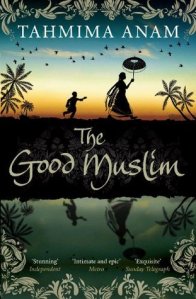

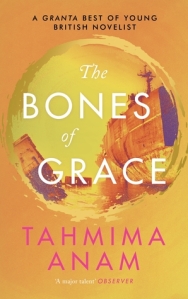

It is also the first novel in the Bangladesh trilogy, the story continues in the books I will be reading next The Good Muslim and the recently published The Bones of Grace.

Tahmima Anam was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh, but grew up in Paris, Bangkok and New York. She earned a Ph.D. in Social Anthropology from Harvard University and a Master’s degree in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway in London. A Golden Age won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book and was the first of a planned trilogy she hoped would teach people about her native country and the vicious power of war.

In 2013 she was included in the Granta list of 20 best young writers and her follow-up novel The Good Muslim was nominated for the 2011 Man Asian Literary Prize.

Dumped with an uncaring relative after his mother dies of consumption Andreas Eggers connects with the mountain more than with the family that barely tolerate him and when he is strong enough to resist the thrashings, will leave and make his own way as a labourer eventually earning sufficient to buy a plot of land up the mountain where he can build a cabin.

Dumped with an uncaring relative after his mother dies of consumption Andreas Eggers connects with the mountain more than with the family that barely tolerate him and when he is strong enough to resist the thrashings, will leave and make his own way as a labourer eventually earning sufficient to buy a plot of land up the mountain where he can build a cabin. Born in Vienna, Austria, Robert Seethaler is an actor (most recently in Paulo Sorrentino’s Youth) and writer, he grew up in Germany and now lives in Berlin. A Whole Life is his fifth novel and the first to be translated into English.

Born in Vienna, Austria, Robert Seethaler is an actor (most recently in Paulo Sorrentino’s Youth) and writer, he grew up in Germany and now lives in Berlin. A Whole Life is his fifth novel and the first to be translated into English. A woman working in an asylum centre as a translator is called to fill in for an interview. She utters the word she has all but banished from her vocabulary. Yes.

A woman working in an asylum centre as a translator is called to fill in for an interview. She utters the word she has all but banished from her vocabulary. Yes.

Human Acts is the author Han Kang’s attempt to make some kind of peace with the knowledge and images of the Gwangju massacre in South Korea in 1980.

Human Acts is the author Han Kang’s attempt to make some kind of peace with the knowledge and images of the Gwangju massacre in South Korea in 1980. Human Acts, which seems to me to be an interesting play on words, is divided into six chapters (or Acts), each from the perspective of a different character affected by the massacre and using a variety of narrative voices.

Human Acts, which seems to me to be an interesting play on words, is divided into six chapters (or Acts), each from the perspective of a different character affected by the massacre and using a variety of narrative voices. I believe in reason and in discussion as supreme instruments of progress, and therefore I repress hatred even within myself: I prefer justice. Precisely for this reason, when describing the tragic world of Auschwitz, I have deliberately assumed the calm, sober language of the witness, neither the lamenting tones of the victim nor the irate voice of someone who seeks revenge. I thought that my account would be all the more credible and useful the more it appeared objective and the less it sounded overly emotional; only in this way does a witness in matters of justice perform his task, which is that of preparing the ground for the judge. The judges are my readers.

I believe in reason and in discussion as supreme instruments of progress, and therefore I repress hatred even within myself: I prefer justice. Precisely for this reason, when describing the tragic world of Auschwitz, I have deliberately assumed the calm, sober language of the witness, neither the lamenting tones of the victim nor the irate voice of someone who seeks revenge. I thought that my account would be all the more credible and useful the more it appeared objective and the less it sounded overly emotional; only in this way does a witness in matters of justice perform his task, which is that of preparing the ground for the judge. The judges are my readers. James Doty never really set out to write this book, but he told his story to so many people with whom it resonated and being one of the founding creators of CCARE (The Center for Compassion and Altruism Research) he was eventually convinced how many more people could be inspired by his story and learn about the amazing work being undertaken, that he agreed to share his experience.

James Doty never really set out to write this book, but he told his story to so many people with whom it resonated and being one of the founding creators of CCARE (The Center for Compassion and Altruism Research) he was eventually convinced how many more people could be inspired by his story and learn about the amazing work being undertaken, that he agreed to share his experience.

The cover is an apt metaphor of the book, where water plays a significant role in multiple turning points in the novel and the image of a woman half-submerged, reminds me of that ability a person has of appearing to cope and be present on and above the surface, when beneath that calm exterior, below in the murky depths, unseen elements apply pressure, disturbing the tranquil image.

The cover is an apt metaphor of the book, where water plays a significant role in multiple turning points in the novel and the image of a woman half-submerged, reminds me of that ability a person has of appearing to cope and be present on and above the surface, when beneath that calm exterior, below in the murky depths, unseen elements apply pressure, disturbing the tranquil image. We arrive in a hill city of Kandy in Sri Lanka where she recounts her solitary, yet idyllic childhood, among the scent of tropical gardens, a big old house, ‘sweeping emerald lawns leading down to the rushing river‘ overlooked by monsoon clouds.

We arrive in a hill city of Kandy in Sri Lanka where she recounts her solitary, yet idyllic childhood, among the scent of tropical gardens, a big old house, ‘sweeping emerald lawns leading down to the rushing river‘ overlooked by monsoon clouds.

Finding a book like this on the English language shelves of our local French library, is one of life’s small pleasures in a world that offers few escapes these days from tragic reality.

Finding a book like this on the English language shelves of our local French library, is one of life’s small pleasures in a world that offers few escapes these days from tragic reality.

The story is narrated in alternate chapters, one entitled Isaac, the other Helen. Isaac takes place during a short period in the life of the male protagonist after he has left the family village somewhere in Ethiopia, planning never to return, arriving in Kampala, a city in Uganda where he hopes to study at the university.

The story is narrated in alternate chapters, one entitled Isaac, the other Helen. Isaac takes place during a short period in the life of the male protagonist after he has left the family village somewhere in Ethiopia, planning never to return, arriving in Kampala, a city in Uganda where he hopes to study at the university. It reminded me a little of Elizabeth Strout’s

It reminded me a little of Elizabeth Strout’s

Lotusland starts out with the main protagonist Nathan, taking a long train journey from Saigon in the south of Vietnam where he lives, to Hanoi, the capital where he will visit his friend Anthony who he hasn’t been in touch with for some time.

Lotusland starts out with the main protagonist Nathan, taking a long train journey from Saigon in the south of Vietnam where he lives, to Hanoi, the capital where he will visit his friend Anthony who he hasn’t been in touch with for some time.

was, I recalled

was, I recalled