The long list for the Man Booker Prize 2015 was announced today, Wednesday 29 July.

The ‘Booker Dozen’ 13 novels feature three British writers, five US writers and one each from the Republic of Ireland, New Zealand, India, Nigeria and Jamaica.

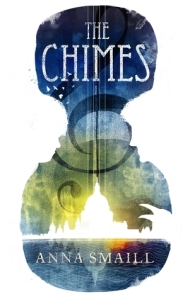

Marlon James, who currently lives in Minneapolis, is the first Jamaican-born author to be nominated for the prize. Laila Lalami, now based in Santa Monica but born in Rabat, is the first Moroccan-born. There are three debut novelists, the literary agent Bill Clegg, Nigerian Chigozie Obioma and New Zealand author Anna Smail.

The longlist is:

Bill Clegg (US) – Did You Ever Have a Family

– On the eve of her daughter’s wedding, June’s life is devastated when a disaster takes the lives of her entire family, all gone in a moment. June is the only survivor.

Anne Enright (Ireland) – The Green Road

Anne Enright (Ireland) – The Green Road

– Spans 30 years, 3 continents and narrates the story of Rosaleen, matriarch of the dysfunctional Irish Madigan family and her four children. Sounds promising.

Marlon James (Jamaica) – A Brief History of Seven Killings

– a fictional exploration of the attempted assassination of Bob Marley in the late 1970s, featuring assassins, journalists, drug dealers, and even ghosts.

Tom McCarthy (UK) – Satin Island

– A “corporate ethnographer,” narrator, U. is tasked with writing the “Great Report,” an all-encompassing document that would sum up our era. A big essay of a novel.

Laila Lalami (US) – The Moor’s Account

Laila Lalami (US) – The Moor’s Account

– the imagined memoirs of the first black explorer of America, a Moroccan slave whose testimony was left out of the official record, historical fiction from 1527.

Chigozie Obioma (Nigeria) – The Fishermen

– In a Nigerian town in the mid 1990’s, four brothers encounter a madman whose mystic prophecy of violence threatens the core of their close-knit family.

Andrew O’Hagan (UK) – The Illuminations

– Anne battles dementia, her grandson Luke is in Afghanistan, on his return they set out for an old guest house where they witness the annual illuminations, dazzling artificial lights that brighten the seaside resort town as the season turns to winter. Love, memory, war and fact.

Marilynne Robinson (US) – Lila

– Revisiting characters and setting of Gilead and Home; Lila, homeless and alone after years of roaming the countryside, steps inside a small-town Iowa church—the only available shelter from the rain—and ignites a romance and a debate that will reshape her life.

Anuradha Roy (India) – Sleeping on Jupiter

– a young girl ends up in an orphanage run by an internationally renowned spiritual guru, before being adopted abroad, haunted by memories, she returns to the temple town of Jarmuli to tie up loose ends and keep promises made long ago, intertwined with the stories of three women she meets on the train.

Sunjeev Sahota (UK) – The Year of the Runaways

– an unlikely family thrown together by circumstance, three men – Tochi, Randeep and Avtar – live together with other migrant workers in a house in Sheffield, all fleeing India and in desperate search of a new life, the woman, Narindar, is married to Randeep but barely knows him and lives in a separate flat.

Anna Smaill (New Zealand) – The Chimes

Anna Smaill (New Zealand) – The Chimes

– set in a reimagined London, a world where people cannot form new memories, the written word forbidden and destroyed. In the absence of both memory and writing is music. Simon Wythern has a gift that could change all that.

Anne Tyler (US) – A Spool of Blue Thread (see review)

Hanya Yanagihara (US) – A Little Life

– follows the complicated relationships of four young men over decades in New York City, their joys and burdens, Jude’s journey to stability, having been scarred by a horrific childhood with its prolonged physical and emotional effects.

***

The only one I have read is Anne Tyler’s A Spool of Blue Thread, the book I’ve been hearing the most about recently, is Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life (albeit in a big fat book), a little too hyped for me and I’m already committed to my #chunkster for summer, which I started today, Chilean Roberto Bolano’s epic 2666.

One of the titles that intrigues me most from the list, that I have also read a few excellent reviews of recently is debut novelist Chigozie Obioma’s The Fishermen.

I’ve also listened to Anne Enright being interviewed and I’m sure The Green Road will be a great read. Based on the blurb alone, I like the sound of Laila Lalami’s historical novel, The Moor’s Account, particularly being a voice and perspective from outside the established literary quarters.

No predictions, but the shortlist of six books will be announced on Tuesday 15 September and the winner on Tuesday 13 October.

So which of these titles appeals to you, or would you like to read?

Laila Lalami (US) – The Moor’s Account

Laila Lalami (US) – The Moor’s Account

Lotusland starts out with the main protagonist Nathan, taking a long train journey from Saigon in the south of Vietnam where he lives, to Hanoi, the capital where he will visit his friend Anthony who he hasn’t been in touch with for some time.

Lotusland starts out with the main protagonist Nathan, taking a long train journey from Saigon in the south of Vietnam where he lives, to Hanoi, the capital where he will visit his friend Anthony who he hasn’t been in touch with for some time.