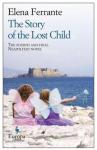

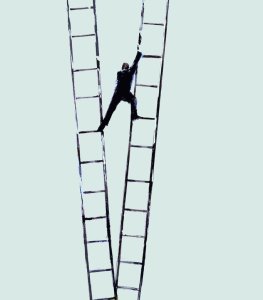

The final book in the Neapolitan Novels tetralogy that began with Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, The Story of the Lost Child continues the saga of two compelling woman, Elena and Lila, childhood friends and now single mothers, back living in the neighbourhood of their humble origins.

At the end of Book 3 Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, Elena was in the midst of a crisis, unable to think or act in anyone’s best interests, rather, she was lead by the wild palpitations of a lust driven heart and appeared to be prepared to risk all she had fought so hard and for so long to rise above and gain.

Now with everything collapsing around her, she returns to her roots, where things are as likely to be in disorder and chaos, but in a place where she feels safe, it is familiar, known.

Elena’s daughters must adapt to a less pampered life, although their mother wishes that they, like her, acquire sufficient education to allow them choices about where and how they might live. Elena and Lila’s children present them both with significant challenges, causing them to move closer together in some respects and further apart when tragedy strikes hard.

As with the previous books, Elena is never quite sure of Lila’s intentions, questioning her motives when she appears helpful and suspicious of her intentions when she informs her of gossip. It is a characteristic of their friendship that has existed since the beginning, an aspect Elena never fully unravels and keeps her always on guard.

‘I went home depressed. I couldn’t drive out the suspicion that she was using me, just as Marcello had said. She had sent me out to risk everything and counted on that bit of fame I had to win her war, to complete her revenge, to silence all her feelings of guilt.’

It is the 1980’s and one of the turning points in Lila’s deterioration is the earthquake that occurred on November 23, 1980 killing 3,000 and rendering 300,000 of Naples inhabitants homeless. It is used as a powerful metaphor for the destabilisation that occurs in Elena and Lila’s lives.

It is the 1980’s and one of the turning points in Lila’s deterioration is the earthquake that occurred on November 23, 1980 killing 3,000 and rendering 300,000 of Naples inhabitants homeless. It is used as a powerful metaphor for the destabilisation that occurs in Elena and Lila’s lives.

‘It expelled the habit of stability and solidity, the confidence that every second would be identical to the next, the familiarity of sounds and gestures, the certainty of recognising them. A sort of suspicion of every form of reassurance took over, a tendency to believe in every prediction of bad luck, an obsessive attention to signs of the brittleness of the world, and it was hard to take control again. Minutes and minutes and minutes that wouldn’t end.’

Elena has always sought her independence and intended to create a career as a writer, it is only when she moves back to the neighbourhood that she realises with greater urgency that she must be autonomous.

‘It was then that a part of me – only a part – began to emerge that consciously, without particularly suffering, admitted that it couldn’t really count on him. It wasn’t just the old fear that he would leave me; rather it seemed to me an abrupt contraction of perspective. I stopped looking into the distance, I began to think that in the immediate future I couldn’t expect from Nino more than what he was giving me, and that I had to decide if it was enough.’

Book Four brings the girls full circle into the adult world where the relationships of childhood and dramas of their youth play out in a more dangerous playground, where boyhood pranks have evolved into criminal activities and the annoying habits of children transform into the damaging actions of adults with far-reaching and destructive consequences.

They are no longer observers of the world around them, they are perpetrators of events and circumstances that will affect the next generation, their children. Though they never wanted it and put all their energy into trying to prevent it, in many ways, they have begun to resemble the already departed, those they worked so hard not to become.

Book Four brings Elena and Lila’s stories back to where it all began, reacquainting us with the story’s beginning, of memories and possessions that have endured, that contain within them that sense of unease alongside the familiar, the two coexist and can not be separated, even in maturity. It is a conclusion of sorts, as thought-provoking as we have come to expect previously, not quite giving in to that alternative literary tradition of tying things up neatly.

I read the first three books in close proximity, each volume adding to the compulsion to want to re-enter their lives and discover what would happen next. The longer gap in awaiting this final novel meant it took a little longer to pick up the pace, suggesting it might be a series best read consecutively.

If you haven’t read Elena Ferrante yet, here are links to reviews of the first three books in this series:

The Neapolitan Novels Reviewed

Book 1: My Brilliant Friend

Book 2: The Story of a New Name

Book 3: Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay

Note: This was an Advance Reader Copy (ARC) thank you to the publisher Europa Editions for kindly providing me with a review copy.

Bride is young, in her twenties, but has learned early the importance of a word, a gesture, a look that can change people’s perception of you, as long as you stick to it, you become known for it, unforgettable, and that one thing can change your world.

Bride is young, in her twenties, but has learned early the importance of a word, a gesture, a look that can change people’s perception of you, as long as you stick to it, you become known for it, unforgettable, and that one thing can change your world.

The novel dwells on certain periods when members of the family return home, the four children are all adults in the opening pages and as the back story is filled in, we observe petty grievances, old resentments, current mysteries and a family coming to term with changes as their parents age and may need to move on from the family home.

The novel dwells on certain periods when members of the family return home, the four children are all adults in the opening pages and as the back story is filled in, we observe petty grievances, old resentments, current mysteries and a family coming to term with changes as their parents age and may need to move on from the family home.