A Reckoning On Race and The Asian Condition

Minor Feelings is a collection of creative nonfiction essays that invites the reader to view aspects of the life experience of artist and writer Cathy Park Hong, from a little observed and known viewpoint, that of an Asian American woman pursuing her own authentic form of expression, while looking for other role models, disrupting the silence that is expected, through a polemic on race, ethnic origins and art.

Minor Feelings is a collection of creative nonfiction essays that invites the reader to view aspects of the life experience of artist and writer Cathy Park Hong, from a little observed and known viewpoint, that of an Asian American woman pursuing her own authentic form of expression, while looking for other role models, disrupting the silence that is expected, through a polemic on race, ethnic origins and art.

There have been a few books published in recent years, on the subject of race and intersectionality, where race intersects with other characteristics such as feminism, gender, class and civil rights.

Cathy Park Hong’s contribution moves between different subjects in seven compelling essays that begin with a memory of her own depression, anger and growing realisation at what was at the core of her disturbance.

In her essays, she deconstructs aspects of life that have contributed to a feeling of oppression and her discovery of artists, comediens and writers, who have overcome something, their example like a stepping stone to her own liberation.

It is a thought provoking exploration of both her own personal experiences and opinions and the examples of other artists, citizens, friends and family that have inspired her to delve into the subject and express a truth.

United

In the opening essay she searches for a therapist, having described what lead her to that moment and then her difficulty in being able to engage with the one she selected.

I wanted a Korean American therapist because then I wouldn’t have to explain myself so much. She’d look at me and just know where I as coming from.

Photo by DS stories on Pexels.com

Her inability to get what she wants or an adequate explanation, followed by a thought provoking conversation with a friend, prove to be defining moments, as she experiences a moment of equanimity, seeing herself from outside of herself, raising her awareness. Her determination and vulnerability fight it out against each other. Intelligence finally wins.

Racial self-hatred is seeing yourself the way the whites see you, which turns you into your own worst enemy. Your only defense is to be hard on yourself, which becomes compulsive, and therefore a comfort, to peck yourself to death.

Her enterprising and persevering father, who studied his way successfully out of rural poverty, immigrated to the US in 1965 when the ban was lifted. The little detail of the hard working father and the frustrated mother provide a barely visible backdrop to the narrative, yet illuminate a strength, highlight contradictions and suggest future avenues not unexplored by this collection.

Stand Up

In this essay she finds inspiration listening to and watching Richard Pryor’s 1979 classic concert film Live in Concert, leading to an epiphany, a brief career in comedy and a deeper understanding of her world.

Pryor told lies – by spinning stories, ranting, boasting, and impersonating everything from a bowling pin to an orgasming hillbilly. And by telling lies, Pryor was more honest about race than most poems and novels I was reading at the time.

The transparency she finds in stand up comedy is like an apprenticeship in opening up and practicing in front of an audience. Comedians can’t pretend they don’t have an identity. They can’t hide behind words, they stand inside them.

It is here she defines for us what ‘minor feelings’ are, acknowledging a debt to cultural theorist Sianne Ngai who wrote extensively on non-cathartic ‘ugly feelings‘ – negative emotions such as envy, irritation and boredom.

Minor feelings occur when American optimism is enforced upon you, which contradicts your own racialized reality, thereby creating a static of cognitive dissonance. You are told, “Things are so much better,” while you think, Things are the same. You are told, “Asian Americans are so successful,” while you feel like a failure. This optimism sets up false expectations that increase this feeling of dysphoria.

The End of White Innocence

Here Park Hong looks sideways at childhood, finding her own definition for what that means, dissecting Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom, set in 1965 – a violent, landmark year for the civil rights movement, the assassination of Malcom X – yet manages to avoid everything outside the nostalgic memories it recreates.

Moonrise Kingdom is just one of countless contemporary films, works of literature, pieces of music, and lifestyle choices where wishing for innocent times means fetishizing an era when the nation was violently hostile to anyone different.

She writes of innocence and shame, of power dynamics, disobedience and indignity.

The alignment of childhood with innocence is an Anglo-American invention that wasn’t popularised until the nineteenth century. Before that in the West, children were treated like little adults who were, if they were raised Calvinist, damned to hell unless they found salvation.

Bad English

Recalling her early school education and affinity with bad English, her fascination with stationery.

It was once a source of shame, but now I say it proudly: bad English is my heritage. I share a literary lineage with writers who make the unmastering of English their rallying cry – who queer it, twerk it, Calibanize it, other it by hijacking English and and warping it to a fugitive tongue.

An Education

The final essays focus on her university years, her influential friendships and the path of being an artist and eventually moving away from painting and sketching towards poetry and narrative.

The greatest gift my parents gave me was making it possible for me to choose my education and career, which I can’t say for the kids I knew in Koreatown who felt bound to lift their parents out of debt and grueling seven-day workweeks.

Her focus is on her friendship with two friends in particular, unapologetically ambitious artists Erin and Helen, deflecting interest in her mother. The poet Hoa Nguyen persevered:

“You have an Asian mother,” she said. “She has to be interesting.”

I must defer, at least for now. I’d rather write about my friendship with Asian women first. My mother would take over, breaching the walls of these essays, until it is only her.

Portrait of an Artist

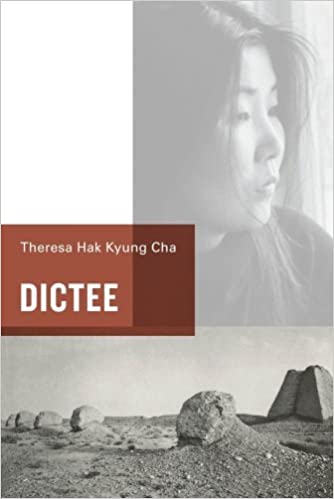

A tribute to thirty one year old artist and poet Theresa Hak Kyung Cha visual artist and poet who on the day she hand delivered an envelope of photographs of hands, for an upcoming group show at Artists Space Gallery, whose book Dictée had just been published, was raped and murdered on her way to join her husband, by a security guard, who knew her.

A tribute to thirty one year old artist and poet Theresa Hak Kyung Cha visual artist and poet who on the day she hand delivered an envelope of photographs of hands, for an upcoming group show at Artists Space Gallery, whose book Dictée had just been published, was raped and murdered on her way to join her husband, by a security guard, who knew her.

Cathy Park Hong comes across Dictée when it is assigned by a visiting professor, ‘a bricolage of memoir, poetry, essay, diagrams and photography.’

Published in 1982..Dictée is about mothers and martyrs, revolutionaries and uprisings. Divided into nine chapters named after the Greek muses, Dictée documents the violence of Korean history through the personal stories of Cha’s mother and the seventeen-year-old Yu Guan Soon, who led the protest against the Japanese occupation of Korea and then died from being tortured by Japanese soldiers in prison.

Struggling to find much out about her, she brings the life of this exceptional artist out of the silence she has been buried, back into focus. What she finds is extraordinary.

The problem with silence is that it can’t speak up and say why it is silent. And so silence collects, becomes amplified, takes on a life outside our intentions, in that silence can get misread as indifference, or avoidance, or even shame, and eventually this silence passes over into forgetting.

The Indebted

The final essay looks back at those to whom she is indebted and discusses this trait as a concept, the weight of it, the gift of it. The difference between indebtedness and gratitude.

Further Listening Reading

Podcast New York Times: Still Processing – The Asian-American poet wants to help women and people of color find healing — and clarity — in their rage. Culture Writers Jenna Wortham & Wesley Moram discuss Minor Feelings & talk to Cathy Park Hong, April 2021

Article The New Yorker: “Minor Feelings” and the Possibilities of Asian-American Identity – Cathy Park Hong’s book of essays bled a dormant discomfort out of me with surgical precision by Jia Tolentino

Interviews – NPR, Goop, Kirkus, NY Times, The Atlantic, Vox, The Yale Review, Medium, Glamour and more.

Cathy Park Hong, Poet, Author

Cathy Park Hong has written three books of poetry Translating Mo’um (2002), Dance, Dance, Revolution (2007) chosen by Adrienne Rich for the Barnard Women Poets Prize, Engine Empire (2012). She is the recipient of the Windham-Campbell Prize and fellowships from Guggenheim, the Fulbright Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York Foundation for the Arts. Her writing on politics and her prose and poetry have appeared in the Village Voice, the Guardian, New Republic, Paris Review, Poetry, Salon, Christian Science Monitor, and New York Times Magazine.

Minor Feelings was a Pulitzer Prize finalist, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for autobiography, and earned her recognition on TIME’s 100 Most Influential People of 2021 list.

She is the poetry editor of the New Republic and is a full professor at Rutgers-Newark University.

“Cathy Park Hong’s brilliant, penetrating and unforgettable Minor Feelings is what was missing on our shelf of classics….To read this book is to become more human.” –Claudia Rankine, author of Citizen

Brit Bennett’s novel features identical African American twins who leave home suddenly to make their way in the world, and looks at all the ways people survive and hide things about themselves, keep secrets and the impact that has not just on themselves but on others around them. And the many ways one can lose oneself.

Brit Bennett’s novel features identical African American twins who leave home suddenly to make their way in the world, and looks at all the ways people survive and hide things about themselves, keep secrets and the impact that has not just on themselves but on others around them. And the many ways one can lose oneself.

Born and raised in Southern California, Brit Bennett graduated from Stanford University and later earned her MFA in fiction at the University of Michigan. Her debut novel

Born and raised in Southern California, Brit Bennett graduated from Stanford University and later earned her MFA in fiction at the University of Michigan. Her debut novel