In Feb 2020 I read Shokoofeh Azar’s epic debut novel, The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree (my review) translated from Farsi. An Iranian writer living in exile in Australia, I was excited to have the opportunity to read a brilliant work of imagination in English. It was later shortlisted for the International Booker Prize (UK), longlisted for a National Book Award for Translated Literature (US) and three Australian Book Awards including the Stella Prize.

Epic and challenging, both that novel and this latest both use elements of magic realism in a unique way to explore recent history, (that of the Iranian Revolution in 1979), while referencing mythic texts and ancient aspects of Iranian culture, which an outsider won’t necessarily pick up on them all, but how incredible a feat, to maintain a compelling plotline that explores the past and uses the metaphysical to assist with confronting situations that are painful to contemplate, creating meaning and helping to overcome trauma.

“Magical realism is not only a realm of boundless imagination, it is also a powerful literary and cultural tool for resisting dominant and imposed powers… I turn to this genre to confront authoritarian structures in Iran while celebrating the true cultural and artistic beauty of my country.”

Preserving a Culture Through Storytelling

Again in The Gowkaran Tree in the Middle of Our Kitchen, Azar writes to embrace and acknowledge family, a beautifully diverse and colourful culture, complex politics, revolution and resistance.

The novel tells a story about a Zoroastrian family with twelve children and a long, interwoven lineage, where the living and the dead are both present and absent, sometimes called on or observed when needed to understand how to navigate the present. Those living in the now are often less aware than those who came before and this connection with their heritage and family is part of the way they survive difficult times.

The story starts with the strange occurrence of a Gowkaran Tree appearing one day in their bustling kitchen, travelling up towards the ceiling, alive with bird life and firmly rooted.

No one but family can see the tree, and while making repairs, their father, a University Professor decides to build a round table around the trunk. The kitchen was their centre and beneath the walls of the old mansion lay the remains of eleven other mansions.

A big, twelve-person table. In this way the Tree of Knowledge, the Tree of Life, the Bas-Tokhmeh Tree, the Gowkaran Tree, the Tree of the Incident, became the kitchen’s centre of gravity.

The grandmother Khanom Joon tells her granddaughter (the narrator Shokoofeh) some of the old family stories, of love and storytelling and the 1,762 notebooks containing the memoirs of their ancestors. She tells her own story and that of the Ball of Light that follows her.

“Curled up in a chair, I let history go and breathed in the air of love and suddenly realised that from now on I was caught. That said, in my dreams I had seen that this madness would grip us both, neither of knowing when it began or how long it would go on. Just like this mansion and this timeless tree and the history of foreigner’s incursions and invasions in this country.”

A Heroine on a Quest, Mentors Abound

I’m not going to even attempt to describe too much of the plot, suffice to say that it is something of the heroine’s journey for the young narrator, who is in the throes of falling in love and will be sent on a quest to search for her brother Mehab, who has gone to fight in the war. A coming-of-age story in harsh times, and yet a celebration of that which continues to resist and persevere and give fruit.

The journey brings to light the terror of a country taken over by despots, and the predicaments of those who capitulate and those who refuse, the voiceless and the silenced. And throughout the Gowkaran Tree remains, rooted, alive and bringing those who remain together.

Why Trees Matter

Trees are a recurring motif in Shokoofeh Azar’s novels. Trees often live on longer than humans, just as our ancestral lineage does, they are places of refuge and transendence.

The rootedness of a big tree in the middle of a kitchen is a symbol of resistance, of strength and the power of deep, familial roots. Its central presence helps preserve what is under threat – family heritage, culture and identity.

The earthy, rooted tree grounds the magical realism element, allowing the author to meander into myth and folklore without losing the connection to the aspects of the story that are firmly rooted in reality. The reader surrenders and goes with it, relieved by the presence of the Ball of Light and terrified by the danger our protagonist is exposed to on her solo journey.

Destiny and Liberty

The book is made up of 27 chapters in two parts, Part One The Womb of Destiny takes place in and around the home mansion and in Part Two The Ordeal of Liberty, our protagonist is sent out alone on her mission to overcome challenges and learn something before her return.

“The way is reached by taking it.”

If you’ve read her earlier works, you’ll be prepared for how unique the storytelling is, but if you’re not a fan of magic realism, this might challenge, however for me it was worth it for the immersion in the storytelling, culture and literary tradition, even if not all the references are familiar. The occasional footnotes are helpful.

The way the plot takes the reader on the journey to save a brother, while encountering historical characters along the way reads like a blend of fable and adventure with philosophical insights mitigating the challenging obstacles required to overcome.

At 512 pages, I admit that once I was out of holiday mode, I set it aside, due to the sheer size of it. I do think it asks a lot from readers today to engage with such a massive book.

Shokoofeh Azar has developed a unique style of magic realism to narrate harsh truths about a society under political and cultural oppression, while sharing its depths of family unity, cultural heritage and dedication to resistance. Overall, I highly recommend it and look forward to where she goes next and hope for a more taut, less ambitious novel next time.

Further Reading

Review: World Literature Today : The Gowkaran Tree in the Middle of Our Kitchen by Andrew Martino

Read a great review at Tony’s Reading List

Iranian Daughters: Struggling for the Rights Their Mothers Lost in the Revolution by Sepideh Zamani

Video Conversation : After the Revolution, Edinburgh Book Festival

Shokoofeh Azar, Author

Born in Iran in 1972, the author worked as a journalist and field reporter in her country, covering human rights issues. After several arrests in connection with her work as a journalist, on advice from her family, she fled Iran in 2010 and was granted asylum in Australia, where she has lived as a political refugee since.

She is the author of essays, articles, and children’s books, and is the first Iranian woman to hitchhike the entire length of the Silk Road.

N.B. Thank you to Europa Editions for the review copy.

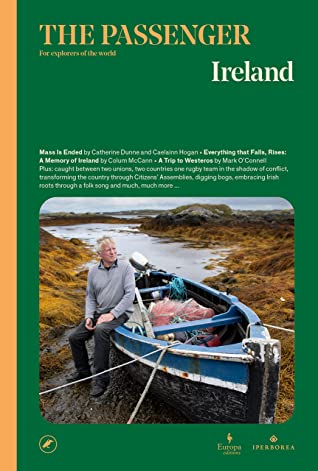

Huginn and Muninn are two ravens from Norse mythology. Sent out by Odin at dawn each day, they return at night to perch on the god’s shoulders, whispering to him whatever knowledge and wisdom they have gathered from every corner of the world. Like Huginn and Muninn The Passenger travels far and wide to bring back the best writing from the countries it visits.

Huginn and Muninn are two ravens from Norse mythology. Sent out by Odin at dawn each day, they return at night to perch on the god’s shoulders, whispering to him whatever knowledge and wisdom they have gathered from every corner of the world. Like Huginn and Muninn The Passenger travels far and wide to bring back the best writing from the countries it visits. Population (the island of Ireland) : 6.9 million (the highest since 1851)

Population (the island of Ireland) : 6.9 million (the highest since 1851)

In Handiwork, she was sculpting birds, but here she writes about the Irish cottage, its evolution and the rise of the Irish villas that were much despised for a period of time. As she spends months creating objects that represent small scale versions of these houses, she reflects on the way Ireland’s built environment has changed.

In Handiwork, she was sculpting birds, but here she writes about the Irish cottage, its evolution and the rise of the Irish villas that were much despised for a period of time. As she spends months creating objects that represent small scale versions of these houses, she reflects on the way Ireland’s built environment has changed.

In A Sister’s Story, we encounter them again; the novel opens with the recall of a graduation celebration at Piero’s parent’s country home. Again the novel is narrated by the unnamed elder sister.

In A Sister’s Story, we encounter them again; the novel opens with the recall of a graduation celebration at Piero’s parent’s country home. Again the novel is narrated by the unnamed elder sister.

If I Had Two Lives is a story of a child who spends her childhood in Vietnam, her early adulthood in America then makes a return visit to her homeland to confront aspects of her past she wishes to resolve.

If I Had Two Lives is a story of a child who spends her childhood in Vietnam, her early adulthood in America then makes a return visit to her homeland to confront aspects of her past she wishes to resolve. “Try telling them some other tales that don’t fit their presumptions. Vietnam” – he dropped his cigarette and crushed it with the toe of his shoe. “Is a war, not a country. Anything besides is irrelevant.”

“Try telling them some other tales that don’t fit their presumptions. Vietnam” – he dropped his cigarette and crushed it with the toe of his shoe. “Is a war, not a country. Anything besides is irrelevant.” “When you leave the old country at an age not young enough to get adopted into the new and not old enough to know how to reject it, you become this mutant thing: between borders, between languages, between memories.” He pressed his temples. “If you ask me, I think it’s easier to reinvent than to retrace. You’re not the only one, you know. Look at this city and its faces. You’re not the only one with an ungraspable history.”

“When you leave the old country at an age not young enough to get adopted into the new and not old enough to know how to reject it, you become this mutant thing: between borders, between languages, between memories.” He pressed his temples. “If you ask me, I think it’s easier to reinvent than to retrace. You’re not the only one, you know. Look at this city and its faces. You’re not the only one with an ungraspable history.”

The novella introduces Salimah, who found herself a job in the supermarket after her husband left her and her two sons as soon as they arrived in this foreign country. She attends an English class for learners of a second language where she meets a Japanese woman named Echnida who brings her small baby to class, an older Italian woman Olive, a group of young Swedish ‘nymphs’ and her teacher. She makes observations about her classmates and her own life, as she learns the language that is her entry into this foreign place.

The novella introduces Salimah, who found herself a job in the supermarket after her husband left her and her two sons as soon as they arrived in this foreign country. She attends an English class for learners of a second language where she meets a Japanese woman named Echnida who brings her small baby to class, an older Italian woman Olive, a group of young Swedish ‘nymphs’ and her teacher. She makes observations about her classmates and her own life, as she learns the language that is her entry into this foreign place. As time passes, new developments replace old situations, opportunities arise, Salimah’s son begins to be invited to play with a school friend, a pregnancy brings the three women together and it is as if they begin to create a community or family between them.

As time passes, new developments replace old situations, opportunities arise, Salimah’s son begins to be invited to play with a school friend, a pregnancy brings the three women together and it is as if they begin to create a community or family between them. I absolutely loved it and was reminded a little of my the experience of sitting in the French language class for immigrants, next to women from Russia, Uzbekistan, Cuba and Vietnam, women with whom it was only possible to converse in our limited French, supported by a teacher who spoke French (or Italian). So many stories, so many challenges each woman had to overcome to contend with life here, most of it unknown to any other, worn on their faces, mysteries the local population were unconcerned with.

I absolutely loved it and was reminded a little of my the experience of sitting in the French language class for immigrants, next to women from Russia, Uzbekistan, Cuba and Vietnam, women with whom it was only possible to converse in our limited French, supported by a teacher who spoke French (or Italian). So many stories, so many challenges each woman had to overcome to contend with life here, most of it unknown to any other, worn on their faces, mysteries the local population were unconcerned with. Iwaki Kei was born in Osaka. After graduating from college, she went to Australia to study English and ended up staying on, working as a Japanese tutor, an office clerk, and a translator. The country has now been her home for 20 years. Farewell, My Orange, her debut novel, won both the Dazai Osamu Prize (a Japanese literary award awarded annually to an outstanding, previously unpublished short story by an unrecognized author) and the

Iwaki Kei was born in Osaka. After graduating from college, she went to Australia to study English and ended up staying on, working as a Japanese tutor, an office clerk, and a translator. The country has now been her home for 20 years. Farewell, My Orange, her debut novel, won both the Dazai Osamu Prize (a Japanese literary award awarded annually to an outstanding, previously unpublished short story by an unrecognized author) and the

The narrating of family stories, taking us back as far as her great-grandfather Montazemolmolk with his harem of 52 wives, serves to provide context and an explanation for why certain family members might have behaved or lived in the way they did, helping us understand their motives and actions.

The narrating of family stories, taking us back as far as her great-grandfather Montazemolmolk with his harem of 52 wives, serves to provide context and an explanation for why certain family members might have behaved or lived in the way they did, helping us understand their motives and actions.

A friend lent me this book and I recognised immediately that it was a Europa Editions book, but not one I had heard of Europa Editions are one of my favourite publishers, they always have something that will appeal to me in their annual catalog. Many of the books are of Italian origin, or translated from other European languages.

A friend lent me this book and I recognised immediately that it was a Europa Editions book, but not one I had heard of Europa Editions are one of my favourite publishers, they always have something that will appeal to me in their annual catalog. Many of the books are of Italian origin, or translated from other European languages.

Both Billy’s father Jack and his best friend Harlow, also bear and have borne the hardship of the return from war, they cope in their own way, as has Marion, Jack’s wife, waiting out the long semi-recovery, which in the early years, tests every man who dares survive war’s dark parasitic claim to their sanity. Now they must watch Billy go through the same test.

Both Billy’s father Jack and his best friend Harlow, also bear and have borne the hardship of the return from war, they cope in their own way, as has Marion, Jack’s wife, waiting out the long semi-recovery, which in the early years, tests every man who dares survive war’s dark parasitic claim to their sanity. Now they must watch Billy go through the same test.