In 2016, I read 55 books, just over my ongoing intention, to read a book a week.

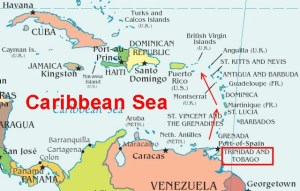

I managed to read books by authors from 26 different countries and 19 of them, just over a third, were translations. My absolute favourite book of the year, was written by an author from Guadeloupe, translated from French into English, and 3 of my top 5 fiction reads were translated.

Outstanding Read of 2016

The book that has stayed with me, that I loved above all else was Simone Schwarz- Bart’s The Bridge of Beyond, a novel that touched on the lives of three generations of women from the French Antillean island of Guadeloupe, narrated by the granddaughter Telumee as she grows up on the island, learning from experience and the traditions of her culture, guided by the wisdom of her grandmother Toussine, ‘Queen Without a Name’. A masterpiece of Caribbean literature, “an unforgettable hymn to the resilience and power of women,” translated from French, republished as a New York Review of Books (NYRB) classic.

Top 5 Fiction Reads

Human Acts, Han Kang (South Korea) tr. Deborah Smith

Human Acts, Han Kang (South Korea) tr. Deborah Smith

As much a work of art as novel, Human Acts is an attempt to understand a despicable act of humanity through story telling, Han Kang was one of the most thought provoking authors of 2016 for me, equally incredible was her novel The Vegetarian, which won the Man Booker International Prize in 2016.

What Lies Between Us, Nayomi Munaweera (Sri Lanka)

What Lies Between Us, Nayomi Munaweera (Sri Lanka)

Like The Bridge of Beyond, Munaweera’s work is evocative of place and she brings a childhood in the gardens of Sri Lanka alive. A woman remembers her past from behind the walls of a cell, and as she reveals her upbringing and the changes that brought her family to live in America, we wonder what went terribly wrong, that caused her to lose everything. And best book cover!

Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston (USA)

Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston (USA)

I finally read this great American classic and it was absolutely fantastic, another story that touches on multiple generations of women and how the lives of each affects the other, as they all wish a different life for the future generation. Janie is determined to live her life differently, but some lessons have to be lived thought and not told. The prose is astounding, melodic and the whole reading experience one I’ll never forget.

Woman at Point Zero, Nawal El Saadawi (Egypt) tr. Sherif Hetata

Woman at Point Zero, Nawal El Saadawi (Egypt) tr. Sherif Hetata

An internationally renowned feminist writer, activist, physician, psychiatrist and prolific writer, I’d been wanting to read her for some time and during August, reading books by Women authors in translation #WITMonth was the perfect opportunity. And what a novel! Inspired by real events, after she was given the opportunity to interview a woman who had been been imprisoned for killing a man and due to be executed, she retells this story of Firdous, too beautiful and poor to pass through life unscathed, who finds the desire to lift herself and others out of oppression and will pay the ultimate price. Haunting, beautiful, a must read author and book!

Days of Abandonment, Elena Ferrante (Italy) tr. Ann Goldstein

Days of Abandonment, Elena Ferrante (Italy) tr. Ann Goldstein

The year wouldn’t be complete without Elena Ferrante, the reclusive Italian author whose identity was outed this year, although I didn’t read any of the reports, preferring she remain as unknown to me now as before. Days of Abandonment was published before her popular tetrology which began with My Brilliant Friend and is a compelling, searing account of one woman’s descent into semi madness following abandonment by her husband, in the days where the hurt prevents her from seeing things objectively and her rationality leaves her. It’s full of tension, as she has two young children and Ferrante uses her incredible talent to make the reader live through the entire uncomfortable experience of this roller coaster ride of temporary insanity.

Top Non Fiction Reads

Memoir

Brother I’m Dying by Edwidge Danticat (Haiti)

Brother I’m Dying by Edwidge Danticat (Haiti)

A beautiful memoir of her father and his brother, alternating between Haiti and America, it is a tribute to a special relationship and an insight into the sacrifices people make to better the lives of others, whether its family or their community. I’ve read her novel Breath, Eyes, Memory she is a wonderful writer with a gift for compassionate storytelling.

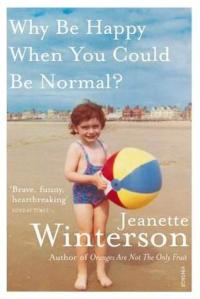

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal by Jeanette Winterson (UK)

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal by Jeanette Winterson (UK)

Wow, this is the adoption memoir that tops all others, a literary tour de force, an entertaining, horrifying account of a young girl’s childhood, survived by a strong passion for life and literature that gets her through some tough moments and develops an iron will to pursue the joy that appeals so much more than the conformity her mother sought. Brilliant.

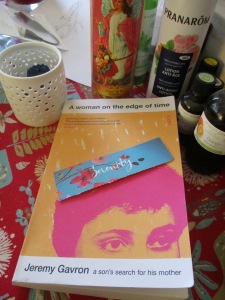

A Woman on the Edge of Time by Jeremy Gavron (UK)

A Woman on the Edge of Time by Jeremy Gavron (UK)

Less a memoir of the son, than one of his obsession to understand why his mother, when she appeared to have everything a young woman would ever want, decided to end it all. Having never asked questions about his mother’s suicide, Jeremy Gavron, now a father of two girls becomes obsessed with knowing who she was and what pressures lead her to her end. Early 1960’s insight.

The Blue Satin Nightgown by Karin Crilly (US)

The Blue Satin Nightgown by Karin Crilly (US)

A reading highlight of the year for me, I’ve seen Karin’s book go through many stages leading to publication this year, in my review you’ll read how I was involved a little in its development. I knew it would be a success, as we sipped champagne together in Aix after she won the Good Life in France short story competition for the first chapter, Scattered Dreams. Last seen, Karin and her friend Judy were in China continuing their adventures, which age will never hamper and there’s a mysterious new man appearing in her recent Facebook posts, suggesting she may be writing a sequel perhaps?

Soul Food

This year, in particular after the harrowing experience accompanying my 14-year-old daughter through back surgery to correct a curvature of the spine, I read a few books by authors published by Hay House, whose radio show I often listen to. I’m already a fan and follower of Colette Baron-Reid and her book Uncharted came out this year, and through her I discovered, listened to and read What if This is Heaven by Anita Moorjani, Making Life Easy by Christiane Northrup and I’m still slow reading a few others. During challenging times, these authors are a soothing balm, reminding us of much we may already know, offering an alternative perspective on how we see things and tips for remaining grounded and healthy in body, mind and spirit.

Special Mentions

Unforgettable Reading Experience Ever: How to Be Brave, Louise Beech(UK)

Unforgettable Reading Experience Ever: How to Be Brave, Louise Beech(UK)

I couldn’t let the year pass without mentioning the extraordinary reading experience of Louise Beech’s How to Be Brave. I read this book while I was in the hospital with my daughter and it was surreal, a captivating, incredible story, based partly on true events, both those of the author and her daughter, who are both coming to terms with a recent diagnosis of Type1 diabetes and a retelling of her grandfather’s epic journey lost at sea, after their ship was destroyed.

Best Translations: Bonjour Tristesse(France) & The Whispering Muse (Iceland)

Best Translations: Bonjour Tristesse(France) & The Whispering Muse (Iceland)

Two fabulous novellas, from Iceland, Sjón’s The Whispering Muse was my first read of the year for 2016 and I loved it, it’s a kind of parody of The Argonauts and had me looking up references to the Greek classic and enjoying both the story and its connections.

Bonjour Tristesse is an excellent, slim summer read, of a young woman’s regret, a heady summer on the French Riviera, engaging as she has a deft ability to portray her minds workings and see herself interacting with the others, aware of her own manipulative ability and yet unable to stop herself. Brilliant.

Best Fictional Biography: Georgia, A Novel of Georgia O’Keeffe, Dawn Tripp (US)

Best Fictional Biography: Georgia, A Novel of Georgia O’Keeffe, Dawn Tripp (US)

I love the work of the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, she’s probably my favourite artist in fact. And she was an incredible woman, who lived a long time and had an intriguing relationship with her husband, who discovered her as one of his protege, the photographer and gallery owner Alfred Steiglitz. Dawn Tripp has done an outstanding job of researching her life, bringing to this novel, insights from new material available and succeeds in doing what hasn’t really been done before, channelling the voice of the artist, providing a perspective that is loyal to the artist and how she may have thought.

Biggest, Most Satisfying Challenge: A Brief History of Seven Killings, Marlon James (Jamaica)

Biggest, Most Satisfying Challenge: A Brief History of Seven Killings, Marlon James (Jamaica)

Written a large part in Jamaican patois, with a wide array of characters, this 700+ page book won the Man Booker Prize in 2015 and was my summer chunkster for 2016. I gave it 5 stars for sheer effort, even though it’s not really my style of book, I tend to prefer the stories by women writers from around the Caribbean, Marlon James is perhaps too modern for me, he moves his story out of generational tradition and into the cold, dark, masculine front lines of survival, jealousy and ambition in a trigger happy, drug induced frightening world that is far from sleepy villages I prefer to inhabit.

Biggest Disappointment: The Fox Was Ever the Hunter, Herta Muller (Romania)(DNF)

It wasn’t on my reading list and I should have listened to my instinct, but since I was reading books by women in translation and I’d been sent this by the publisher (unsolicited), and it was a novel by a Nobel Prize winning author I attempted it. Impossible. Incomprehensible. Stop. Prize winning authors and books should be looked at like any other book I tell myself, forget about what a committee of 18 Swedish writers, linguists, literary scholars, historians and a prominent jurist with life tenure think, they are not you.

Well that’s it for 2016, another great reading year!

What was your outstanding read for 2016?

It is a novel narrated in parts, each part focusing on a character(s) who were influential in her life, including the young man who never knew her until this day, the one who became her confidant, perhaps the first man she ever trusted, after all that had passed beforehand. Much of it is told as Mala slips into memories of herself as child, reliving it.

It is a novel narrated in parts, each part focusing on a character(s) who were influential in her life, including the young man who never knew her until this day, the one who became her confidant, perhaps the first man she ever trusted, after all that had passed beforehand. Much of it is told as Mala slips into memories of herself as child, reliving it. As Tyler gained her trust, Mala’s story is revealed to us through him and through the two visitors she received, who on her first day there, unable to see her, left a pot with a cutting of the fragrant night-blooming cereus plant, a gift that clearly delighted her, a symbol of fragrant, nurturing oblivion.

As Tyler gained her trust, Mala’s story is revealed to us through him and through the two visitors she received, who on her first day there, unable to see her, left a pot with a cutting of the fragrant night-blooming cereus plant, a gift that clearly delighted her, a symbol of fragrant, nurturing oblivion.

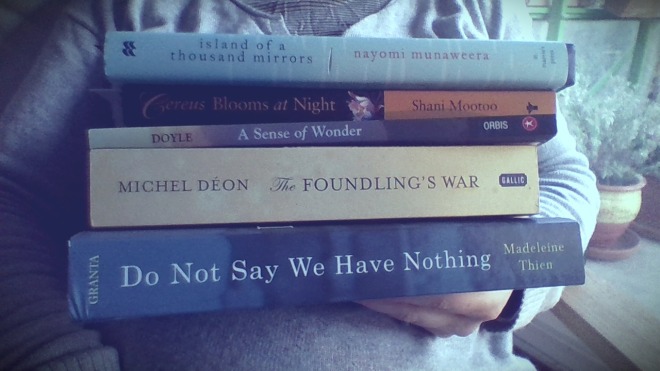

Island of a Thousand Mirrors similarly evokes the childhoods and family life of two families living in the same house. The house is owned by the matriarch Sylvia Sumethra and her husband The Judge, who are Sinhala people (an Indo-Aryan ethnic group originally from northern India, now native to and forming the majority (75%) of the population of Sri Lanka, mostly Buddhist) and upstairs they rent to an extended Tamil family (a culturally and linguistically distinct ethnic group native to Sri Lanka, mostly Hindu).

Island of a Thousand Mirrors similarly evokes the childhoods and family life of two families living in the same house. The house is owned by the matriarch Sylvia Sumethra and her husband The Judge, who are Sinhala people (an Indo-Aryan ethnic group originally from northern India, now native to and forming the majority (75%) of the population of Sri Lanka, mostly Buddhist) and upstairs they rent to an extended Tamil family (a culturally and linguistically distinct ethnic group native to Sri Lanka, mostly Hindu).

Three Daughters of Eve

Three Daughters of Eve Exit West

Exit West The Good People

The Good People Breaking Connections

Breaking Connections Train to Pakistan

Train to Pakistan Written as a reflection on the death of her daughter at 39 years of age, the book begins as Didion thinks back to her daughter’s wedding seven years earlier, which then triggers other memories of her childhood, of family moments, of people and places, numerous hotels they have frequented.

Written as a reflection on the death of her daughter at 39 years of age, the book begins as Didion thinks back to her daughter’s wedding seven years earlier, which then triggers other memories of her childhood, of family moments, of people and places, numerous hotels they have frequented. Although the main theme of the book is her daughter’s premature death, nowhere does she analyse or obsess about what actually happened in the way we vividly remember she did about her husband in My Year of Magical Thinking. Rather, the book appears to be as much an acknowledgement of her own ageing and decline, recognising and facing up to her own ‘frailty’, her obsession with her own health scares, recounting every little malfunction or symptom of a thing that never shows up on any of the numerous scans or tests she has. It is as if she writes her own denouement, to a death that never arrives, as the multitude and thoroughness of all the tests she has show how very much alive and in relative good health she is, despite herself.

Although the main theme of the book is her daughter’s premature death, nowhere does she analyse or obsess about what actually happened in the way we vividly remember she did about her husband in My Year of Magical Thinking. Rather, the book appears to be as much an acknowledgement of her own ageing and decline, recognising and facing up to her own ‘frailty’, her obsession with her own health scares, recounting every little malfunction or symptom of a thing that never shows up on any of the numerous scans or tests she has. It is as if she writes her own denouement, to a death that never arrives, as the multitude and thoroughness of all the tests she has show how very much alive and in relative good health she is, despite herself.

Unforgettable Reading Experience Ever:

Unforgettable Reading Experience Ever:  Best Translations:

Best Translations:  Best Fictional Biography:

Best Fictional Biography:  Biggest, Most Satisfying Challenge:

Biggest, Most Satisfying Challenge:

Jacky Guard takes Betty to New Zealand as his wife and they set up home in a bay that is handy for their whaling activities and where it is easy to trade with the native Maori population. Jacky trades with, though doesn’t trust the Maori Rangatira (chief), Te Rauparaha. He is able to negotiate with him, but fears he may have disrespected some of their taboo beliefs. There are constant challenges to their attempt to settle on this land, each time they return to Sydney, their home and belongings are often burned on their return.

Jacky Guard takes Betty to New Zealand as his wife and they set up home in a bay that is handy for their whaling activities and where it is easy to trade with the native Maori population. Jacky trades with, though doesn’t trust the Maori Rangatira (chief), Te Rauparaha. He is able to negotiate with him, but fears he may have disrespected some of their taboo beliefs. There are constant challenges to their attempt to settle on this land, each time they return to Sydney, their home and belongings are often burned on their return. Elizabeth Parker, the Real Betty Guard

Elizabeth Parker, the Real Betty Guard

Ocean Echoes follows a period in the life of a marine researcher named Ellen, who is dedicated to her work, the study of jellyfish, her main desire to discover a new species. She has become ever more focused on her work since a major betrayal that crossed both personal and professional boundaries, an experience that has made her cautious of becoming close to others and less trusting about divulging the findings of her research.

Ocean Echoes follows a period in the life of a marine researcher named Ellen, who is dedicated to her work, the study of jellyfish, her main desire to discover a new species. She has become ever more focused on her work since a major betrayal that crossed both personal and professional boundaries, an experience that has made her cautious of becoming close to others and less trusting about divulging the findings of her research. “One of our gods in Mala legend is the fierce sea monster Minawaka. He was once the guardian of the reef entrance to our island. He would change into a shark and travel through the reef, challenging others to fight. But whenever he fought as a shark, great waves would form, valleys would flood, and there would be much suffering…Until one day a giant octopus grew tired of the waves and the suffering caused from all this fighting. This octopus snuck up behind Minawaka and coiled his tentacles around him. The octopus began to squeeze. Minawaka begged for mercy and agreed never to fight again or harm anyone from the island of Mala.”

“One of our gods in Mala legend is the fierce sea monster Minawaka. He was once the guardian of the reef entrance to our island. He would change into a shark and travel through the reef, challenging others to fight. But whenever he fought as a shark, great waves would form, valleys would flood, and there would be much suffering…Until one day a giant octopus grew tired of the waves and the suffering caused from all this fighting. This octopus snuck up behind Minawaka and coiled his tentacles around him. The octopus began to squeeze. Minawaka begged for mercy and agreed never to fight again or harm anyone from the island of Mala.”

This was my first read of Christiane Northrup, despite the fact she’s written lots of books, with titles like: Goddesses Never Age: The Secret Prescription for Radiance, Vitality, and Well-Being, The Wisdom of Menopause: Creating Physical and Emotional Health and Healing During the Change and Women’s Bodies, Women’s Wisdom: Creating Physical and Emotional Health and Healing (39 editions published).

This was my first read of Christiane Northrup, despite the fact she’s written lots of books, with titles like: Goddesses Never Age: The Secret Prescription for Radiance, Vitality, and Well-Being, The Wisdom of Menopause: Creating Physical and Emotional Health and Healing During the Change and Women’s Bodies, Women’s Wisdom: Creating Physical and Emotional Health and Healing (39 editions published). The health and sexuality sections held less interest to me, probably because I was attracted to the book after listening to her speak in a ‘raw and real’ conversation with my favourite ‘intuitive’ Colette Baron-Reid, in that conversation it was the more spiritual aspects that were under discussion, particularly as Colette’s book Uncharted: The Journey through Uncertainty to Infinite Possibility had been published in October 2016. Northrup is a fan of Colette Baron-Reid and mentions that she uses her Wisdom of the Oracle card deck as one of her spiritual tools for guidance.

The health and sexuality sections held less interest to me, probably because I was attracted to the book after listening to her speak in a ‘raw and real’ conversation with my favourite ‘intuitive’ Colette Baron-Reid, in that conversation it was the more spiritual aspects that were under discussion, particularly as Colette’s book Uncharted: The Journey through Uncertainty to Infinite Possibility had been published in October 2016. Northrup is a fan of Colette Baron-Reid and mentions that she uses her Wisdom of the Oracle card deck as one of her spiritual tools for guidance. She also discusses thoughts and inputs, the effect of what we are constantly exposed to and how it should be managed in order to avoid overdosing on negativity and the toxic, fear-enhancing effect of the media for example. She discusses the positive power of affirmations, meditation, gratitude, the power of giving and receiving, connecting with nature, tapping and much more.

She also discusses thoughts and inputs, the effect of what we are constantly exposed to and how it should be managed in order to avoid overdosing on negativity and the toxic, fear-enhancing effect of the media for example. She discusses the positive power of affirmations, meditation, gratitude, the power of giving and receiving, connecting with nature, tapping and much more.

A Woman on the Edge of Time is a memoir that reads like a mystery, as Jeremy Gavron, a journalist, interviews family, old school friends, neighbours and colleagues of his mother Hannah Gavron, whom he has little memory of.

A Woman on the Edge of Time is a memoir that reads like a mystery, as Jeremy Gavron, a journalist, interviews family, old school friends, neighbours and colleagues of his mother Hannah Gavron, whom he has little memory of.

This stylised memoir, set in the working-class north of England, is the book Jeanette Winterson wasn’t ready to write back in 1985 when at 25 years of age, she wrote the novel Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, a book that plunged the reader into her universe, one that provided the author the liberty of narrating freely, without the confines of the story having to have been exactly as she had lived it – it was fiction, an imagined story, and she named the main character Jeanette, a provocative gesture for sure.

This stylised memoir, set in the working-class north of England, is the book Jeanette Winterson wasn’t ready to write back in 1985 when at 25 years of age, she wrote the novel Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, a book that plunged the reader into her universe, one that provided the author the liberty of narrating freely, without the confines of the story having to have been exactly as she had lived it – it was fiction, an imagined story, and she named the main character Jeanette, a provocative gesture for sure.