March is Reading Ireland month, an initiative created by Cathy at 746 Books and it is simply a way of being in community, while reading anything written by Irish authors or that relates to Ireland, there are no fixed rules, just the intention to Read Ireland, whatever that means to you! There’s even a Spotify playlist if you’re interested in a bit of musical culture.

Getting a Jump Start

For me that means reading more Irish authors from my bookshelves. I did read two in January, in fact my first read of 2025 was Donal Ryan’s Irish Book Award 2024 winning, heart, be at peace, a novel about multiple characters in a rural town in County Tipperary facing the different issues that face them a decade or so on from his debut novel The Spinning Heart.

Then I picked up a beautiful second hand hardback Water by John Boyne on holiday, and read it on my flight home. It is the first of four novellas in his The Elements series and now I want to read the next three, Earth, Fire and the final one Air due out in May 2025. But not yet, I’m prioritising what I already have!

Reading From the Shelves

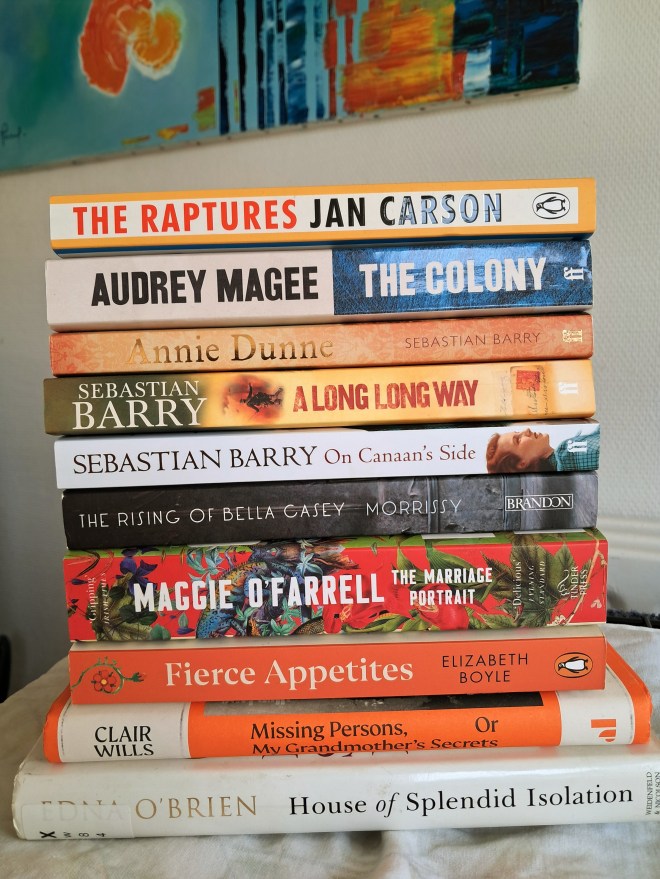

So here is the pile from my bookshelves, from which I will be choosing what to read in March 2025.

There are also three titles languishing on my kindle, which doesn’t get as much attention as it should, because out of sight is out of mind when it comes to reading. So I’m jogging my memory and will try to read at least one of these e-books.

On the kindle I have Listening Still by Anne Griffin, The Quiet Whispers Never Stop by Olivia Fitzsimons and Quickly, While They Still Have Horses by Jan Carson. In physical print I have another Carson The Raptures, that I picked up at the annual Ansouis vide grenier in September 2024.

Audrey Magee’s The Colony (2022) was longlisted for the Booker Prize, shortlisted for the Orwell Prize for political fiction and the Kerry Group Irish Novel award, so it gained a lot of attention and I have been keen to read it.

When Fiction Reminds Us of Those Who’ve Passed

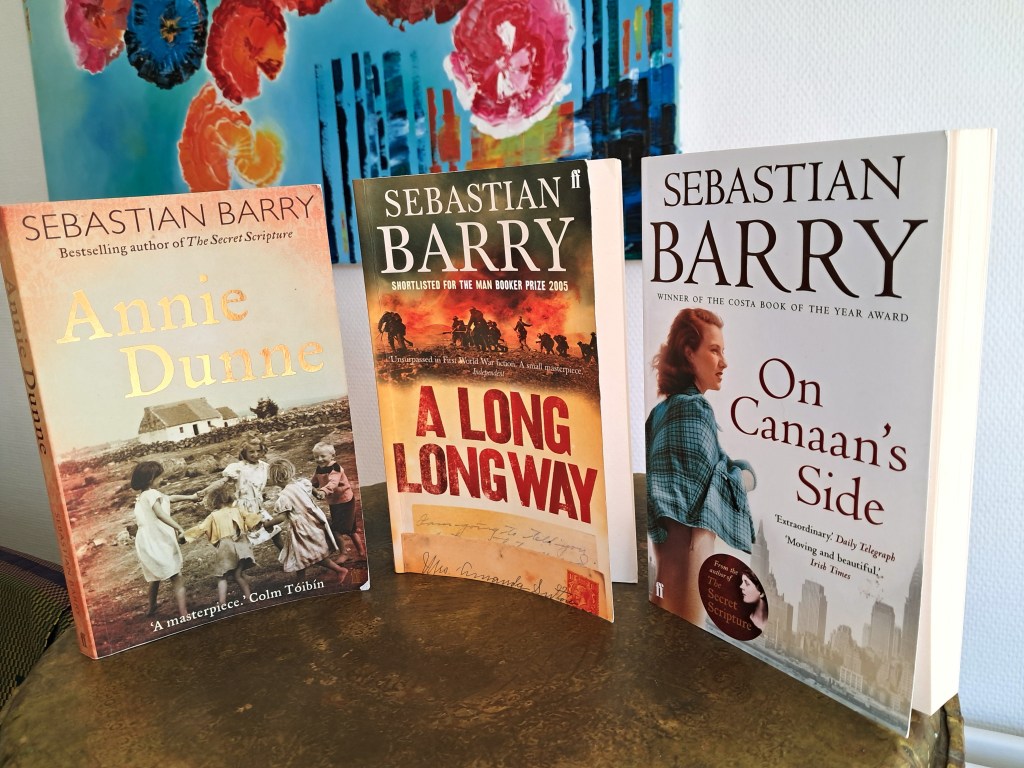

I really enjoyed Sebastian Barry’s Old God’s Time (2023) and want to read more of his work, so I chose his Dunne Family trio of books, Annie Dunne (2002), A Long Long Way (2005) and On Canaan’s Side (2011) to delve more into his storytelling. I am part way through reading these now.

I love that this collection of novels and the play that was the first in the series, were all inspired by characters from his own ancestral lineage. That inspired me too.

After reading A Long Long Way, I became curious, as I too have an ancestor, born in the same year as his character Willie Dunne (1896), who like Willie, went to France in World War I, was in an Irish regiment and did not return. My ancestor Edmund Costley died on 9 April 1916, in Ypres, West Flanders, Belgium at the age of 19. I’ll be writing a post about him in April.

Historical Re-Imaginings, True Crime, Women’s Lot

I have read two novels by Mary Morrissey, Mother of Pearl (1995) and Penelope Unbound (2023). Morrissey tends to take historical stories and/or characters and re-imagine their lives. Mother of Pearl was inspired by a notorious baby-snatching case in 1950’s Ireland, that she chose to fictionalise, having said that the truth would have come across to readers as unbelievable; while Penelope Unbound re-imagines the life of Nora Barnacle, if in Trieste, Italy, when James Joyce made her wait all day outside a train station for him, she decides to leave.

This year I’m going to read her imagined autobiography, The Rising of Bella Casey (2013); she was the sister of the acclaimed playwright Sean O’Casey, and it is set at the turn of the century Dublin, a social commentary on the lives of women in that era.

Then there is Maggie O’Farrell’s The Marriage Portrait (2022), another historical re-imagining, this time of the short life of Lucrezia de’ Medici, a sixteenth century member of the renowned aristocratic House of Medici in Italy. I enjoyed O’Farrell’s riveting memoir I Am, I Am, I Am – Seventeen Brushes With Death (2017), the first of her works I read, and then the multiple award-winning, Hamnet (2020) and The Hand That First Held Mine (2010), so I’m looking forward to immersing in this one.

Irish Non-Fiction

There are two non-fiction titles on my pile, Missing Persons, Or My Grandmother’s Secrets by Claire Wills, author, critic and cultural historian, winner of the Irish Book Award for non-fiction, who has written a family history that blends memoir with social history. She explores the gaps in that history, brought about by Ireland’s brutal treatment of unmarried mother’s and their babies, and a culture of not caring, not looking into or asking questions, rolling back a dark period of its history of loss and forgetting.

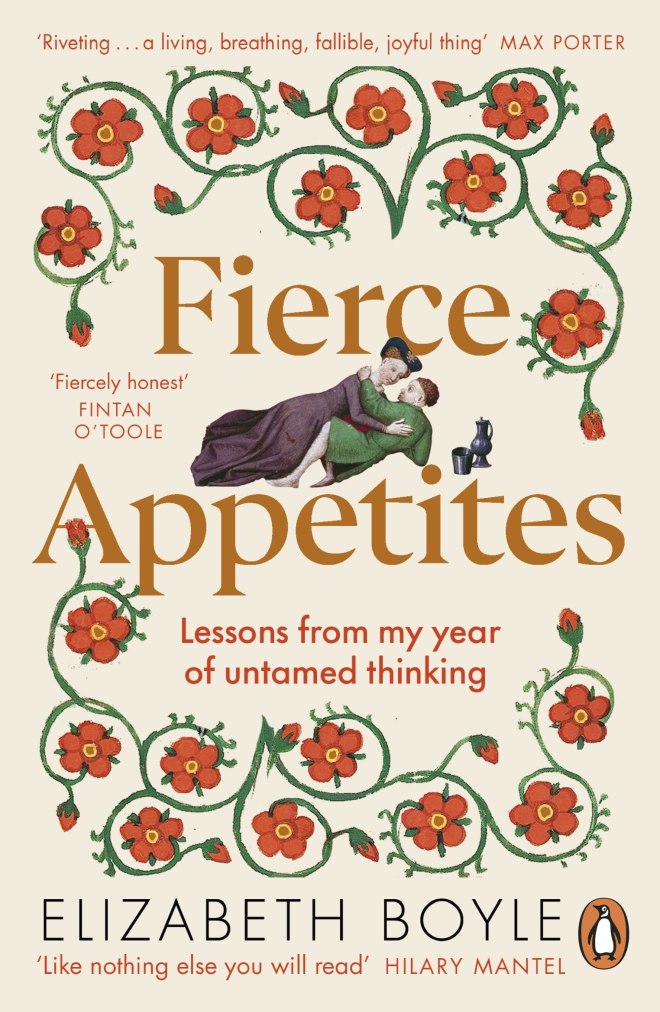

The second non-fiction title is the candid Fierce Appetites – lessons from my year of untamed thinking, also subtitled, Loving, Losing and Living to Excess in my Present and in the Writings of the Past by medieval historian Elizabeth Boyle.

The title is a reference to Vivian Gornick’s memoir Fierce Attachments, which is part of what intrigued me, but also the uniqueness of someone finding sense of three dramatic events in their life through medieval literature.

Every day a beloved father dies. Every day a lover departs. Every day a woman turns forty.All three happening together brings a moment of reckoning.

Boyle writes on grief, addiction, family breakdown, the complexities of motherhood, love and sex, memory, class, education, travel (and staying put), with unflinching honesty,deep compassion and occasional dark humour.

Remembering Edna O’Brien (15 December 1930 – 27 July 2024)

I couldn’t read Ireland without adding a title from Edna O’Brien, who died in 2024 at the age of 93. In 2023, I read The Country Girls trilogy, made up of three stories The Country Girls (1960), The Lonely Girl (1962), and Girls in Their Married Bliss (1964) released in 1986 in a convenient single volume.

Credited with breaking the silence on issues young girls faced growing up in Ireland, it was a subject she would often return to. She was punished for it, but lead the way for others to eventually follow.

O’Brien described her work in this way:

I have depicted women in lonely, desperate, and often humiliated situations, very often the butt of men and almost always searching for an emotional catharsis that does not come. This is my territory and one that I know from hard-earned experience. Edna O’Brien (Roth, 1984, p. 6)

Cathy at 746 Books and Kim at Reading Matters are spending a year reading Edna O’Brien and are reading Country Girls in February, you can see their reading schedule for the year if you go to their blog.

I have decided to read one my shelf, The House of Splendid Isolation (1991), the first book in her Modern Ireland trilogy, a political novel, depicting the relations of an Irish Republican Army terrorist and his hostage, an ageing Irish widow, in a house that represents the troubled nation.

Suggestions, Recommendations?

That’s the selection I have made, no guarantees on what I’ll get through, but I’m looking forward to the immersion. Have you read and enjoyed of the titles I mention above?

Are you going to read any Irish literature in March? Let me know in the comments below.

Grand, tells the story of Noelle McCarthy’s growing up in Hollymount, County Cork and the highs and lows of being around a mother, who had already lost two children before she was born and was herself never comforted by her own mother. Seeking to self-regulate through the effect of alcohol, Grand demonstrates numerous effects of having been raised under those circumstances and how a multi-faceted generational trauma passes down.

Grand, tells the story of Noelle McCarthy’s growing up in Hollymount, County Cork and the highs and lows of being around a mother, who had already lost two children before she was born and was herself never comforted by her own mother. Seeking to self-regulate through the effect of alcohol, Grand demonstrates numerous effects of having been raised under those circumstances and how a multi-faceted generational trauma passes down.

Noelle McCarthy is an award-winning writer and radio broadcaster. Her story ‘Buck Rabbit’ won the Short Memoir section of the Fish Publishing International Writing competition in 2020 and this memoir Grand won the Best First Book General Nonfiction Award at the NZ Book Awards 2023.

Noelle McCarthy is an award-winning writer and radio broadcaster. Her story ‘Buck Rabbit’ won the Short Memoir section of the Fish Publishing International Writing competition in 2020 and this memoir Grand won the Best First Book General Nonfiction Award at the NZ Book Awards 2023.

I don’t have any Irish nonfiction left unread on my shelf, but I have noted that creative nonfiction author Kerri ní Dochartaigh, whose debut

I don’t have any Irish nonfiction left unread on my shelf, but I have noted that creative nonfiction author Kerri ní Dochartaigh, whose debut  If you are looking for inspiration, check out Cathy’s blog, where she shares a list of

If you are looking for inspiration, check out Cathy’s blog, where she shares a list of

Victoria Bennett was born in Oxfordshire in 1971. A poet and author, her writing has previously received a Northern Debut Award, a Northern Promise Award, the Andrew Waterhouse Award, and has been longlisted for the Penguin WriteNow programme and the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize for under-represented voices.

Victoria Bennett was born in Oxfordshire in 1971. A poet and author, her writing has previously received a Northern Debut Award, a Northern Promise Award, the Andrew Waterhouse Award, and has been longlisted for the Penguin WriteNow programme and the inaugural Nan Shepherd Prize for under-represented voices. Dear Senthuran is a collection of letters to what we might call Emezi’s inner circle, past and present.

Dear Senthuran is a collection of letters to what we might call Emezi’s inner circle, past and present. Emezi writes about the experience and feelings of being unsupported during some of the challenges they faced and about their determination not to compromise when it became clear the debut novel was going to sell.

Emezi writes about the experience and feelings of being unsupported during some of the challenges they faced and about their determination not to compromise when it became clear the debut novel was going to sell.

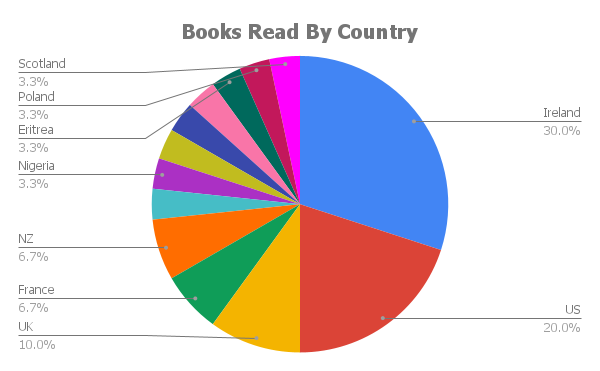

Though I read less than half the number of books of 2021, I did manage to read 30 books from 13 countries, a third Irish authors, thanks to Cathy’s annual

Though I read less than half the number of books of 2021, I did manage to read 30 books from 13 countries, a third Irish authors, thanks to Cathy’s annual

All About Love: New Visions, bell hooks (US)

All About Love: New Visions, bell hooks (US)

What My Bones Know, A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma, Stefanie Foo (US) (Memoir)

What My Bones Know, A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma, Stefanie Foo (US) (Memoir)

My Father’s Daughter, Hanna Azieb Pool (UK/Eritrea) (Adoptee Memoir)

My Father’s Daughter, Hanna Azieb Pool (UK/Eritrea) (Adoptee Memoir)