I read My Name is Mary Sutter when it first came out and was utterly entranced by Robin Oliveira’s depiction of the character of Mary, a midwife intent on becoming a surgeon in an era where women were totally blocked from pursuing such a thing. She was unable to achieve her ideal through formal channels, so she went to war, the American civil war, and there had the kind of experience few would wish her, unless, like Mary, you were being excluded from pursuing your desired profession and were driven to break through irrational barriers by equally irrational means.

In her research, the author learned that 17 young women became physicians after their nursing experiences in the civil war. While Mary Sutter is fictional, she is a truly inspired character about whom Robin Oliveira had this is say:

“And through it all there was Mary Sutter, whose story I needed to tell as a celebration of women who seize the courage to live on, to thrive, to strive, even, when men conspire to war. Mary, flawed and intelligent, careening between desire and remorse, stumbling forward out of courage and stubbornness, hiding a broken heart, but hoping to redeem something beautiful from a life humbled by regret.”

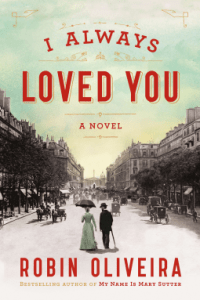

Her second novel, set in Paris was the excellent I Always Loved You, reviewed here, is about the American painter Mary Cassatt, her life in Paris, struggling to make a name while remaining true to her art, and enduring a life-long fractious relationship with impressionist painter and sculptor Edgar Degas.

When asked what made her return, in this her third historical novel, to the character of Mary Sutter, Robin Oliveira said:

Over the last few years, readers have often asked me to include Mary Sutter in a new book, but I could not think of a single circumstance that would challenge her as much as the obstacles she had faced in the Civil War. Then I learned about the age of consent. I simply couldn’t leave Mary Sutter out of it, for I had finally discovered something of equal importance for her to battle.

So now it is 1869 in Albany, New York, Mary Sutter is now Dr Mary Sutter Stipps, living in Albany, New York, where she practices in a local hospital, despite most of her male colleagues despising her (because she is a woman), she also runs a home practice with her husband William Stipp and a lesser known clinic, where a lantern is illuminated on Thursdays when she opens for ladies of the night, those who are refused treatment elsewhere.

So now it is 1869 in Albany, New York, Mary Sutter is now Dr Mary Sutter Stipps, living in Albany, New York, where she practices in a local hospital, despite most of her male colleagues despising her (because she is a woman), she also runs a home practice with her husband William Stipp and a lesser known clinic, where a lantern is illuminated on Thursdays when she opens for ladies of the night, those who are refused treatment elsewhere.

These are the conservative years after the civil war, a period of tumultuous struggle and the emergence of women’s suffrage, meaning any freedoms women attempted to gain were often fiercely opposed and ridiculed. Mary faces opposition at every turn, but refuses to be cowered and will stand up for and insist on justice for what she believes is right and good.

On the evening this story begins, a severe winter blizzard disrupts the city, children are locked in schools for two days, businesses close, the Doctors house their patients overnight, and accidents occur – two days later as people begin to reappear, Mary learns of the deaths of close family friends, the hatmaker Bonnie and her labourer husband David and the unexplained disappearance of their daughters, Emma(10) and Claire(7).

Mary and William search for the girls everywhere, implore the police and their wider networks to help and eventually must accept they’ve gone.

At the graveside, they become acquainted with lumberlord Gerritt Van der Veer, his wife Viola, and their son Jakob. From that day on the lives of the two families become intertwined, as Mary continues her relentless pursuit of the lost girls, leading her to become exposed to the deep manipulations throughout the city and its powerful, by those out to benefit themselves who will do anything to stop those like her, trying to help and heal, without discrimination or judgement.

Book One sets up the story, introducing us to Elisabeth, Mary’s niece, a violin protegé who has been studying in Paris in the company of her grandmother Amelia, who swiftly return on hearing the terrible news, though laden with their own mysterious troubles.

Mary seeks the help of the women she’s met through the clinic, women who hear and see things she and Will would never come across, suspicions begin to arise, as they become aware of a man in hiding, injured on the night the ice cracks on the Hudson River, causing flash flooding across the city.

Mary seeks the help of the women she’s met through the clinic, women who hear and see things she and Will would never come across, suspicions begin to arise, as they become aware of a man in hiding, injured on the night the ice cracks on the Hudson River, causing flash flooding across the city.

“I trust her Mother. She’s no opportunist. If she’d wanted money, she would have asked for it then, wouldn’t she have, if she intended to lie? And besides, none of that matters, does it, if we go looking ourselves. The brothels are the single place we haven’t looked. What harm can come from looking? I can’t understand why Captain Mantel refused. Oh damn him.The police know exactly where the brothels are. it would be easy for them.”

By Book Two the story has become riveting, complex, there are elements of the mystery to resolve, a pending court case, perceived betrayals, all set against the legal and societal background of the times they lived in, there are aspects of the law that will shock the reader, we read about the 1800’s and we are reminded of the similar treatment of victims today with regard to police procedure, questioning victims and the law that appears designed to protect the accused more than the victim.

It’s too good a read to give away anything more that happens from Book Two onwards, suffice to say I could not put this down, I was up late finishing it and thought it brilliantly woven together. It’s commentary on the hardships of women and girls, of all ages and from all classes is insightful and outrageous. Women are blocked in so many directions, in particular when they possess talent, controlled, commented on, kept by men in positions of power. Fortunately, there are exceptions, and these characters provide the faint glimmer of hope that gets us through the tough parts.

“He wanted to say, It’s either hide forever or see forever. He wanted to say, You need to choose. He wanted to say, Follow me, I’ll show you…

Every inch toward courage was a decision. Every ten feet on her own would be a triumph. The line between coercion and choice for her was the line between darkness and light. He would never push her, but she needed to choose to climb this hill. If she didn’t, she wouldn’t have the courage to climb onto the witness stand or perhaps even to walk down a street on her own.”

Mary Sutter oversteps the demarcated line of acceptable professions for women, she breaks the mould, though not without challenge and William and Jakob show themselves to be different kind of men, demonstrating the potential of working alongside women, not excluding them.

The price women pay when they overstep that societal and male control, is the story of the Gilded Age, and continues to play out one hundred and fifty years later. Indeed, the changing role of women in society, and what men will accept, remains one of the essential conflicts of our time.

Highly recommended, one of the best historical novels of the year.

Note: This book was an ARC (Advance Reader Copy) kindly provided by the publisher.

In The Heart’s Invisible Furies, a title taken from a quote by Hannah Arendt, the German-born American political theorist:

In The Heart’s Invisible Furies, a title taken from a quote by Hannah Arendt, the German-born American political theorist:

Reservoir 13 was long listed for the

Reservoir 13 was long listed for the  This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness.

This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness. It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s

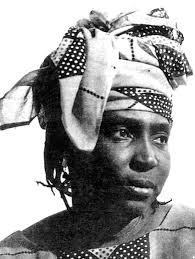

It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s  Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.

Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.

Once I got into the rhythm of this, which is to say, reading in French, and getting past the need to look up too many new words, I couldn’t put this down, by the time I found my reading rhythm, the lives of Gabriel (Gaby) and his sister Ana, his parents, his friends had their claws in me and I had to know what was going to happen next.

Once I got into the rhythm of this, which is to say, reading in French, and getting past the need to look up too many new words, I couldn’t put this down, by the time I found my reading rhythm, the lives of Gabriel (Gaby) and his sister Ana, his parents, his friends had their claws in me and I had to know what was going to happen next. His father is French, his mother Tutsi from Rwanda, they live in the small country bordering Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo, called Burundi. It boasts the second deepest lake in the world, Lake Tanganyika, which occupies a large portion of the country’s border and is part of the African Great Lakes region.

His father is French, his mother Tutsi from Rwanda, they live in the small country bordering Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo, called Burundi. It boasts the second deepest lake in the world, Lake Tanganyika, which occupies a large portion of the country’s border and is part of the African Great Lakes region.

The ending is not really an ending, it could be said there is more than one ending and perhaps there may even be another book. I found it incredibly moving and was amazed to be so moved in a language that is not my own. An incredible feat of writing, a wonderful talent.

The ending is not really an ending, it could be said there is more than one ending and perhaps there may even be another book. I found it incredibly moving and was amazed to be so moved in a language that is not my own. An incredible feat of writing, a wonderful talent. Sing, Unburied, Sing is set in the same Southern US community, putting us amidst a struggling mixed race family, a young black woman Leonie, who fell in love with Michael from a racist white family implicated in a tragedy that affected her family. In its telling, it traverses love, grief, terminal illness, addiction, prejudice, dysfunctional parenting, hope and survival, the effect this mix has on everyone touched by it, the painful and the poignant.

Sing, Unburied, Sing is set in the same Southern US community, putting us amidst a struggling mixed race family, a young black woman Leonie, who fell in love with Michael from a racist white family implicated in a tragedy that affected her family. In its telling, it traverses love, grief, terminal illness, addiction, prejudice, dysfunctional parenting, hope and survival, the effect this mix has on everyone touched by it, the painful and the poignant. There is a reference to her novel Salvage The Bones, as the family return from their road trip, they pass a young couple walking a dog, it is the brother and sister, Skeetah and Eschelle, from the neighbourhood, protagonists of that earlier novel. I was curious to know if the dog was related to China, an unresolved thread left hanging from her earlier novel. I was delighted to encounter them.

There is a reference to her novel Salvage The Bones, as the family return from their road trip, they pass a young couple walking a dog, it is the brother and sister, Skeetah and Eschelle, from the neighbourhood, protagonists of that earlier novel. I was curious to know if the dog was related to China, an unresolved thread left hanging from her earlier novel. I was delighted to encounter them.