Although I’ve read reviews and seen this book appear often over the last year, and knew I really wanted to read it, I couldn’t remember what is was about or why.

Although I’ve read reviews and seen this book appear often over the last year, and knew I really wanted to read it, I couldn’t remember what is was about or why.

It was down to a consistent feeling and feedback from readers whose views I respect, their brief tweets of encouragement igniting the flame of motivation that made me choose this as the first #WIT (Women in Translation) novel I’d read in August 2018. Yes, it is WIT Month again, now in its 5th year!

So how to describe this remarkable novel?

There’s a clue in the two versions of the English translations, (the American and British English versions have different titles and different translators). The novel was originally written in French and ironically one of the characters, a 50-year-old woman awaiting a heart transplant in a Parisian hospital, is also a translator.

The American translation (by Sam Taylor) is entitled The Heart and it is indeed a story that follows the heart of a 19-year-old youth from the moment his alarm clock rings at 5.50 a.m one morning, an hour he rarely awakes, as he sets off with two friends on a surfing mission during a rare mid-winter half-tide; over the next 24 hours until his body is meticulously prepared to be laid to rest.

He lets out a whoop as he takes his first ride, and for a period of time he touches a state of grace – its horizontal vertigo, he’s neck and neck with the world, and as though issued from it, taken into its flow – space swallows him, crushes him as it liberates him, saturates his muscular fibres, his bronchial tubes, oxygenates his blood; the wave unfolds on a blurred timeline, slow or fast it’s impossible to tell, it suspends each second one by one until it finishes pulverised, an organic, senseless mess and it’s incredible but after having been battered by pebbles in the froth at the end, Simon Limbeau turns to go straight back out again.

The British translation (by Jessica Moore) is entitled Mend the Living, broader in scope, it references the many who lie with compromised organs, who dwell in a twilight zone of half-lived lives, waiting to see if their match will come up, knowing when it does, it will likely be a sudden opportunity, to receive a healthy heart, liver, or kidney from a donor, taken violently from life.

The British translation (by Jessica Moore) is entitled Mend the Living, broader in scope, it references the many who lie with compromised organs, who dwell in a twilight zone of half-lived lives, waiting to see if their match will come up, knowing when it does, it will likely be a sudden opportunity, to receive a healthy heart, liver, or kidney from a donor, taken violently from life.

It could also refer to those who facilitate the complex conversations and interventions, those with empathy and sensitivity who broach the subject to parents not yet able to comprehend, let alone accept what is passing – to those with proficiency, who possess a singular ambition to attain perfection in their chosen field, harvesting and transplanting organs.

Maylis de Kerangal writes snapshots of scenes that pass on this one day, entering briefly into the personal lives of those who have some kind of involvement in the event and everything that transpires connected to it, in the day that follows.

It’s like the writer wields a camera, zooming in on the context of the life of each person; the parents, separated, who will be brought together, the girlfriend confused by a long silence, the nurse waiting for a text message from last nights tryst, the female intern following in the family tradition, the Doctor who she will shadow removing thoughts of the violent passion of the woman he abandoned when his pager went off, and the one who bookends the process who listens to the questions and requests, who respects the concerns of the living and the dead, the one who sings and is heard.

Within the hospital, the I.C.U. is a separate space that takes in tangential lives, opaque comas, deaths foretold – it houses those bodies situated exactly at the point between life and death. A domain of hallways and rooms where suspense holds sway.

The translator Jessica Moore refers to her task in translating the authors work, as ‘grappling with Maylis’s labyrinthe phrases’, which can feel like what it must be like to be an amateur surfer facing the wave, trying and trying again, to find the one that fits, the wave and the rider, the words and the translator. She gives up trying to turn what the author meant into suitable phrases and leaves interpretation to the future, potential reader, us.

The translator Jessica Moore refers to her task in translating the authors work, as ‘grappling with Maylis’s labyrinthe phrases’, which can feel like what it must be like to be an amateur surfer facing the wave, trying and trying again, to find the one that fits, the wave and the rider, the words and the translator. She gives up trying to turn what the author meant into suitable phrases and leaves interpretation to the future, potential reader, us.

It is an extraordinary novel in its intricate penetration and portrayal of medical procedure, it’s obsession with language, with extending its own vocabulary, its length of phrase, as if we are riding a wave of words, of long sentences strung out across a shoreline, that end with a dumping in the shallows.

In the process of writing the book, the author’s own father had a heart attack, which put the writing on hold and sent her thinking to even greater depths:

“A few months later I was in Marseille and I wanted to understand what is a heart. I began to think about its double nature: on the one hand you have an organ in your body and on the other you have a symbol of love. From that time I started to pursue the image of a heart crossing the night from one body to another. It is a simple narrative structure but it’s open to a lot of things. I had the intuition that this book could give form to my intimate experience of death.”

This is one of those novels that unleashes the mind and sends it off in all kinds of directions, thinking about the impact events have on so many lives, the different callings people have, the incredible developments in medical science, how little we really know and yet how some do seem to know intuitively and can act in ways that restores our faith in humanity.

A deserving winner of the Wellcome Book Prize in 2017, a prize that rewards books that illuminate the human experience through its interaction with health, medicine and illness, literature engaging with science and medical themes, the book has also been made into a successful film and two stage productions.

Highly Recommended.

Interview with Maylis de Kerangal – What is a Heart? by Claire Armistead

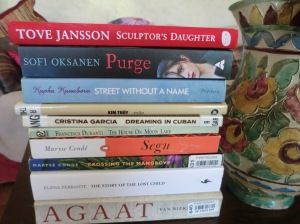

Nothing Holds Back the Night is the book Delphine de Vigan avoided writing until she could no longer resist its call. It is a book about her mother Lucile, who she introduces to us on the first page as she enters her apartment and discovers her sleeping, the long, cold, hard sleep of death. Her mother was 61-years-old.

Nothing Holds Back the Night is the book Delphine de Vigan avoided writing until she could no longer resist its call. It is a book about her mother Lucile, who she introduces to us on the first page as she enters her apartment and discovers her sleeping, the long, cold, hard sleep of death. Her mother was 61-years-old. I read this book in a day, it’s one of those narratives that once you start you want to continue reading, it’s described as autofiction, a kind of autobiography and fiction, though there is little doubt it is the story of the author’s mother, as she constructs thoughts and dialogue inspired by the information provided by family members, acknowledging that for many of the events, some often have a different memory which she even shares.

I read this book in a day, it’s one of those narratives that once you start you want to continue reading, it’s described as autofiction, a kind of autobiography and fiction, though there is little doubt it is the story of the author’s mother, as she constructs thoughts and dialogue inspired by the information provided by family members, acknowledging that for many of the events, some often have a different memory which she even shares. The Complete Claudine by Colette tr. Antonia White (French) – Colette began her writing career with Claudine at School, which catapulted the young author into instant, sensational success. Among the most autobiographical of Colette’s works, these four novels are dominated by the child-woman Claudine, whose strength, humour, and zest for living make her a symbol for the life force.

The Complete Claudine by Colette tr. Antonia White (French) – Colette began her writing career with Claudine at School, which catapulted the young author into instant, sensational success. Among the most autobiographical of Colette’s works, these four novels are dominated by the child-woman Claudine, whose strength, humour, and zest for living make her a symbol for the life force.

On the day when the nation is shocked and grieving after a devastating earthquake, that has destroyed entire villages and resulted in a significant loss of life, I don’t know how appropriate it is to share their literature, perhaps in the case of this particular novel, it serves to put things in perspective.

On the day when the nation is shocked and grieving after a devastating earthquake, that has destroyed entire villages and resulted in a significant loss of life, I don’t know how appropriate it is to share their literature, perhaps in the case of this particular novel, it serves to put things in perspective. A national bestseller for almost an entire year, The Days of Abandonment shocked and captivated its Italian public when first published.

A national bestseller for almost an entire year, The Days of Abandonment shocked and captivated its Italian public when first published.

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche.

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche. It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese.

It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese. Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors.

Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors. Two sisters have lived in the same house all their lives, their parents long gone and they can barely tolerate each other. They are bound together in one sense due to the practical disability of the younger sister, but also through the inherent sense of duty and responsibility of the first-born.

Two sisters have lived in the same house all their lives, their parents long gone and they can barely tolerate each other. They are bound together in one sense due to the practical disability of the younger sister, but also through the inherent sense of duty and responsibility of the first-born.