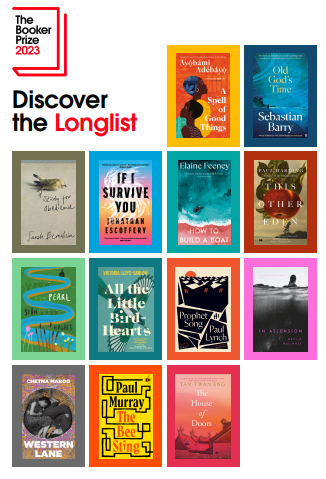

The Booker Prize longlist has been announced, featuring books from four continents, representing seven countries – Scotland, England, Ireland, Canada, America, Nigeria and Malaysia and includes four Irish writers plus four debut novelists.

You can read more about the history of the prize here.

The Judges

Novelist Esi Edugyan, twice-shortlisted for the Booker Prize, is the chair of the 2023 judging panel. She is joined by actor, writer and director Adjoa Andoh; poet, lecturer, editor and critic Mary Jean Chan; Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and Shakespeare specialist James Shapiro; and actor and writer Robert Webb.

The judges are looking for their perceived best sustained work of long-form fiction written in English, selected from entries published in the UK and Ireland between October 1, 2022 and September 30, 2023.

The Booker Dozen

The longlist of 13 books was announced on August 1, 2023 ; the shortlist of six books will follow on September 21 and the winner of the £50,000 prize will be announced on November 26, 2023.

The 13 longlisted books explore universal and topical themes: from deeply moving personal dramas to tragi-comic family sagas; from the effects of climate change to the oppression of minorities; from scientific breakthroughs to competitive sport.

The list includes:

- 10 writers longlisted for the first time, including four debut novelists

- Three writers with seven previous nominations between them

- Writers from seven countries across four continents

- Four Irish writers, making up a third of the longlist for the first time

- A novel featuring a neurodiverse protagonist, written from personal experience

- ‘All 13 novels cast new light on what it means to exist in our time, and they do so in original and thrilling ways,’ according to Esi Edugyan, Chair of the judges

The House of Doors – by Tan Twan Eng

Based on real events, Tan Twan Eng’s masterful novel of public morality and private truth examines love and betrayal under the shadow of Empire

It is 1921 and at Cassowary House in the Straits Settlements of Penang, Robert Hamlyn is a well-to-do lawyer, his steely wife Lesley a society hostess. Their lives are invigorated when Willie, an old friend of Robert’s, comes to stay.

Willie Somerset Maugham is one of the greatest writers of his day. But he is beleaguered by an unhappy marriage, ill-health and business interests that have gone badly awry. He is also struggling to write. The more Lesley’s friendship with Willie grows, the more clearly she see him as he is – a man who has no choice but to mask his true self.

As Willie prepares to face his demons, Lesley confides secrets of her own, including her connection to the case of an Englishwoman charged with murder in the Kuala Lumpur courts – a tragedy drawn from fact, and worthy of fiction.

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray (Ireland)

A patch of ice on the road, a casual favour to a charming stranger, a bee caught beneath a bridal veil – can a single moment of bad luck change the direction of a life?

Dickie’s once-lucrative car business is going under – but rather than face the music, he’s spending his days in the woods, building an apocalypse-proof bunker. His exasperated wife Imelda is selling off her jewellery on eBay while half-heartedly dodging the attentions of fast-talking cattle farmer Big Mike.

Meanwhile, teenage daughter Cass, formerly top of her class, seems determined to binge-drink her way to her final exams. And 12-year-old PJ, in debt to local sociopath ‘Ears’ Moran, is putting the final touches to his grand plan to run away.

Yes, in Paul Murray’s brilliant tragicomic saga, the Barnes family is definitely in trouble. So where did it all go wrong? And if the story has already been written – is there still time to find a happy ending?

Western Lane by Chetna Maroo (Kenya/London)

Chetna Maroo’s tender and moving debut novel about grief, sisterhood, a teenage girl’s struggle to transcend herself – and squash

Eleven-year-old Gopi has been playing squash since she was old enough to hold a racket. When her mother dies, her father enlists her in a quietly brutal training regimen, and the game becomes her world.

Slowly, she grows apart from her sisters. Her life is reduced to the sport, guided by its rhythms: the serve, the volley, the drive, the shot and its echo. But on the court, she is not alone. She is with her pa. She is with Ged, a 13-year-old boy with his own formidable talent. She is with the players who have come before her. She is in awe.

Skilfully deploying the sport of squash as both context and metaphor, Western Lane is a deeply evocative debut about a family grappling with grief, conveyed through crystalline language which reverberates like the sound “of a ball hit clean and hard…with a close echo”

In Ascension by Martin MacInnes (Scotland)

Exploring the natural world with wonder and reverence, this compassionate, deeply inquisitive epic reaches outward to confront the great questions of existence, while looking inward to illuminate the human heart

Leigh grew up in Rotterdam, drawn to the waterfront as an escape from her unhappy home life. Enchanted by the undersea world of her childhood, she excels in marine biology, travelling the globe to study ancient organisms.

When a trench is discovered in the Atlantic Ocean, Leigh joins the exploration team, hoping to find evidence of Earth’s first life forms. What she instead finds calls into question everything we know about our own beginnings, and leaves her facing an impossible choice: to remain with her family, or to embark on a journey across the breadth of the cosmos.

In this strange and wonderful world, every outward journey – whether to space or the depths of the ocean – is an inward one, as Leigh seeks to move beyond her troubled childhood. In Ascension is a Solaris for the climate-change age.

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch (Ireland)

A mother faces a terrible choice, in Paul Lynch’s exhilarating, propulsive and confrontational portrait of a society on the brink

On a dark, wet evening in Dublin, scientist and mother-of-four Eilish Stack answers her front door to find the GNSB on her doorstep. Two officers from Ireland’s newly formed secret police want to speak with her husband.

Things are falling apart. Ireland is in the grip of a government that is taking a turn towards tyranny. And as the blood-dimmed tide is loosed, Eilish finds herself caught within the nightmare logic of a collapsing society – assailed by unpredictable forces beyond her control and forced to do whatever it takes to keep her family together.

Paul Lynch’s harrowing and dystopian Prophet Song vividly renders a mother’s determination to protect her family as Ireland’s liberal democracy slides inexorably and terrifyingly into totalitarianism. Readers will find it timely and unforgettable. It’s a remarkable accomplishment for a novelist to capture the social and political anxieties of our moment so compellingly.

All the Little Bird-Hearts by Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow (England)

Viktoria Lloyd-Barlow’s lyrical and poignant debut novel offers a deft exploration of motherhood, vulnerability and the complexity of human relationships

Sunday Forrester does things more carefully than most people. On quiet days, she must eat only white foods. Her etiquette handbook guides her through confusing social situations, and to escape, she turns to her treasury of Sicilian folklore. The one thing very much out of her control is Dolly – her clever, headstrong daughter, now on the cusp of leaving home.

Into this carefully ordered world step Vita and Rollo, a charming couple who move in next door.

Written from the perspective of an autistic mother, All the Little Bird-Hearts is a poetic debut which masterfully intertwines themes of familial love, friendship, class, prejudice and trauma with psychological acuity and wit.

Pearl by Siân Hughes (England)

Siân Hughes contemplates both the power and the fragility of the human mind in her haunting debut novel, which was inspired by the medieval poem of the same name

Marianne is eight years old when her mother goes missing. Left behind with her baby brother and grieving father in a ramshackle house on the edge of a small village, she clings to the fragmented memories of her mother’s love; the smell of fresh herbs, the games they played, and the songs and stories of her childhood.

As time passes, Marianne struggles to adjust, fixated on her mother’s disappearance and the secrets she’s sure her father is keeping from her. Discovering a medieval poem called Pearl – and trusting in its promise of consolation – Marianne sets out to make a visual illustration of it, a task that she returns to over and over but somehow never manages to complete.

Tormented by an unmarked gravestone in an abandoned chapel and the tidal pull of the river, her childhood home begins to crumble as the past leads her down a path of self-destruction. But can art heal Marianne? And will her own future as a mother help her find peace?

Pearl, an exceptional debut novel, is both a mystery story and a meditation on grief, abandonment and consolation, evoking the profundities of the haunting medieval poem. The degree of difficulty in writing a book of this sort – at once quiet and hugely ambitious – is very high. It’s a book that will be passed from hand to hand for a long time to come.

This Other Eden by Paul Harding (USA)

Full of lyricism and power, Paul Harding’s spellbinding novel celebrates the hopes, dreams and resilience of those deemed not to fit in a world brutally intolerant of difference

Inspired by historical events, This Other Eden tells the story of Apple Island: an enclave off the coast of the United States where castaways – in flight from society and its judgment – have landed and built a home.

In 1792, formerly enslaved Benjamin Honey arrives on the island with his Irish wife, Patience, to make a life together there. More than a century later, the Honeys’ descendants remain, alongside an eccentric, diverse band of neighbours.

Then comes the intrusion of ‘civilization’: officials determine to ‘cleanse’ the island. A missionary schoolteacher selects one light-skinned boy to save. The rest will succumb to the authorities’ institutions – or cast themselves on the waters in a new Noah’s Ark…

Based on a relatively unknown true story, Paul Harding’s heartbreakingly beautiful novel transports us to a unique island community scrabbling a living. The panel were moved by the delicate symphony of language, land and narrative that Harding brings to bear on the story of the islanders.

How to Build a Boat by Elaine Feeney (Ireland) (Read my review here)

With tenderness and verve, Elaine Feeney tells the story of how one boy on a unique mission transforms the lives of his teachers, and brings together a community

Jamie O’Neill loves the colour red. He also loves tall trees, patterns, rain that comes with wind, the curvature of many objects, books with dust jackets, cats, rivers and Edgar Allan Poe.

At the age of 13, there are two things he especially wants in life: to build a Perpetual Motion Machine, and to connect with his mother Noelle, who died when he was born. In his mind, these things are intimately linked.

And at his new school, where all else is disorientating and overwhelming, he finds two people who might just be able to help him.

The interweaving stories of Jamie, a teenage boy trying to make sense of the world, and Tess, a teacher at his school, make up this humorous and insightful novel about family and the need for connection. Feeney has written an absorbing coming-of-age story which also explores the restrictions of class and education in a small community. A complex and genuinely moving novel.

If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery (USA)

An exhilarating novel-in-stories that pulses with style, heart and barbed humour, while unravelling what it means to carve out an existence between cultures, homes and pay checks

In 1979, as political violence consumes their native Kingston, Topper and Sanya flee to Miami. But they soon learn that the welcome in America will be far from warm.

Trelawny, their youngest son, comes of age in a society that regards him with suspicion and confusion. Their eldest son Delano’s longing for a better future for his own children is equalled only by his recklessness in trying to secure it.

As both brothers navigate the obstacles littered in their path – an unreliable father, racism, a financial crisis and Hurricane Andrew – they find themselves pitted against one another. Will their rivalry be the thing that finally tears their family apart?

An astonishingly assured debut novel, lauded by the panel for its clarity, variety and fizzing prose. As the stories move back and forth through geography and time, we are confronted by the immigrants’ eternal questions: who am I now and where do I belong?

Study for Obedience by Sarah Bernstein (Canada/Scotland)

In her accomplished and unsettling second novel, Sarah Bernstein explores themes of prejudice, abuse and guilt through the eyes of a singularly unreliable narrator

A woman moves from the place of her birth to a ‘remote northern country’ to be housekeeper to her brother, whose wife has just left him. Soon after she arrives, a series of unfortunate events occurs: collective bovine hysteria; the death of a ewe and her nearly-born lamb; a local dog’s phantom pregnancy; a potato blight.

She notices that the community’s suspicion about incomers in general seems to be directed particularly in her case. She feels their hostility growing, pressing at the edges of her brother’s property. Inside the house, although she tends to her brother and his home with the utmost care and attention, he too begins to fall ill…

Study for Obedience is an absurdist, darkly funny novel about the rise of xenophobia, as seen through the eyes of a stranger in an unnamed town – or is it? Bernstein’s urgent, crystalline prose upsets all our expectations, and what transpires is a meditation on survival itself.

Old God’s Time by Sebastian Barry (Ireland) (Read my review here)

In his beautiful, haunting novel, in which nothing is quite what it seems, Sebastian Barry explores what we live through, what we live with, and what may survive of us

Recently retired policeman Tom Kettle is settling into the quiet of his new home, a lean-to annexed to a Victorian Castle overlooking the Irish Sea. For months he has barely seen a soul, catching only glimpses of his eccentric landlord and a nervous young mother who has moved in next door.

Occasionally, fond memories of the past return – of his family, his beloved wife June and their two children. But when two former colleagues turn up at his door with questions about a decades-old case, one which Tom never quite came to terms with, he finds himself pulled into the darkest currents of his past.

A Spell of Good Things by Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀ (Nigeria/Norwich)

A dazzling story of modern Nigeria and two families caught in the riptides of wealth, power, romantic obsession and political corruption

Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀’s breathtaking novel shines a light on the haves and have-nots of Nigeria, and the shared humanity that lives in between.

Eniola is tall for his age, a boy who looks like a man. His father has lost his job, so Eniola spends his days running errands, collecting newspapers and begging – dreaming of a big future. Wuraola is a golden girl, the perfect child of a wealthy family, and now an exhausted young doctor in her first year of practice. But when sudden violence shatters a family party, Wuraola and Eniola’s lives become inextricably intertwined…

A Spell of Good Things is an examination of class and desire in modern-day Nigeria. While Eniola’s poverty prevents him from getting the education he desperately wants, Wuraola finds that wealth is no barrier against life’s harsher realities. A powerful, staggering read.

* * * * * * * * * *

Have you read any of these novels, or are you tempted by any? A great many unknown authors here, which is exciting, it will be interesting to see how their stories are received by readers.

I haven’t read any of the books mentioned and I have only read two of the nominated authors, Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀’s Stay With Me which I really enjoyed and Tan Twan Eng’s The Gift of Rain and The Garden of Evening Mists.

I’m always interested in new Irish fiction, so I’ll be taking a good look at those titles and plan to read at the very least, Old God’s Time and How To Build A Boat.

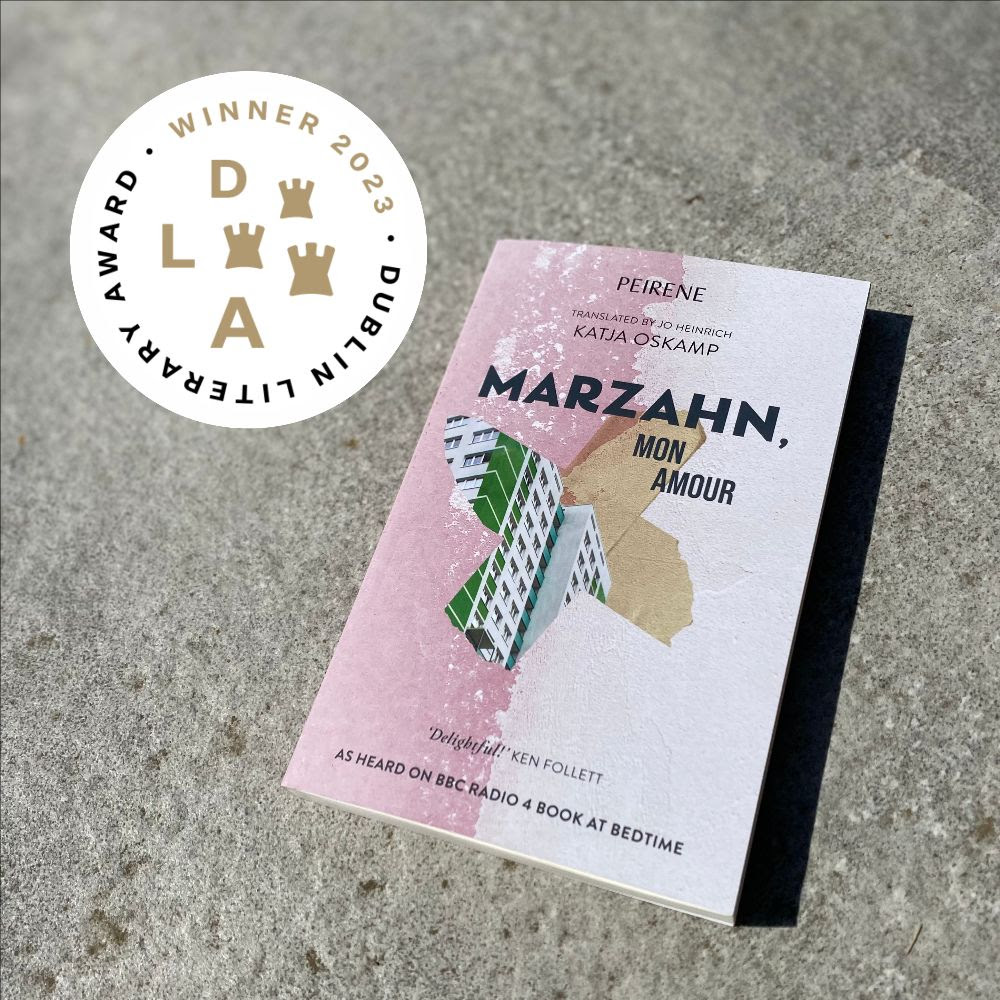

Marzhan Mon Amour is a memoir-ish novel, collective history and a character study of a group of people living in and around a multi-storied communist-era plattenbau prefab apartment building in the working class quarter of Marzahn, East Berlin, told through the eyes and ears of a woman facing her middle years.

Marzhan Mon Amour is a memoir-ish novel, collective history and a character study of a group of people living in and around a multi-storied communist-era plattenbau prefab apartment building in the working class quarter of Marzahn, East Berlin, told through the eyes and ears of a woman facing her middle years.

One that didn’t win, but that was Number 4 in The People’s Choice and one I have heard a lot about and sighted on a recent visit to London, is

One that didn’t win, but that was Number 4 in The People’s Choice and one I have heard a lot about and sighted on a recent visit to London, is  River Spirit is a unique work of historical fiction set in 1890’s Sudan, at a turning point in the country’s history, as its population began to mount a challenge against the ruling Ottoman Empire, only the people were not united, due to the opposition leadership coming from a self-proclaimed “Mahdi” – a religious figure that many Muslims believe will appear at the end of time to spread justice and peace.

River Spirit is a unique work of historical fiction set in 1890’s Sudan, at a turning point in the country’s history, as its population began to mount a challenge against the ruling Ottoman Empire, only the people were not united, due to the opposition leadership coming from a self-proclaimed “Mahdi” – a religious figure that many Muslims believe will appear at the end of time to spread justice and peace. The change in perspective and the lack of a first person narrative keeps the characters at a slight distance to the reader as we follow the trials of Zamzam’s life and her dedication to being a part of Yaseen’s life. Like other readers, I wished at times that the story was told in the first person from her point of view, but the story is too important to be limited to one perspective.

The change in perspective and the lack of a first person narrative keeps the characters at a slight distance to the reader as we follow the trials of Zamzam’s life and her dedication to being a part of Yaseen’s life. Like other readers, I wished at times that the story was told in the first person from her point of view, but the story is too important to be limited to one perspective. Once Akuany and her brother leave the family village, most of the story takes place in Khartoum, a city that is at the confluence of the Blue Nile and the White Nile, two major rivers that join to become the Nile proper, the longest river in the world, that continues on through Egypt to the Mediterranean.

Once Akuany and her brother leave the family village, most of the story takes place in Khartoum, a city that is at the confluence of the Blue Nile and the White Nile, two major rivers that join to become the Nile proper, the longest river in the world, that continues on through Egypt to the Mediterranean. Leila Aboulela is a fiction writer, essayist, and playwright of Sudanese origin. Born in Cairo, she grew up in Khartoum and moved in her mid-twenties to Aberdeen, Scotland. Her work has received critical recognition and a high profile for its depiction of the interior lives of Muslim women and its distinctive exploration of identity, migration and Islamic spirituality.

Leila Aboulela is a fiction writer, essayist, and playwright of Sudanese origin. Born in Cairo, she grew up in Khartoum and moved in her mid-twenties to Aberdeen, Scotland. Her work has received critical recognition and a high profile for its depiction of the interior lives of Muslim women and its distinctive exploration of identity, migration and Islamic spirituality. Though not an easy read, Pod is a work of inspired literary genius. A cetacean epic, it is a fictional account of dolphin tribe rivalry and a coming-of-age of story of one of the pod, created from real knowledge of environmental science and marine biology. Clearly, a lot of background research and animal behavioural understanding underpins the narrative.

Though not an easy read, Pod is a work of inspired literary genius. A cetacean epic, it is a fictional account of dolphin tribe rivalry and a coming-of-age of story of one of the pod, created from real knowledge of environmental science and marine biology. Clearly, a lot of background research and animal behavioural understanding underpins the narrative.