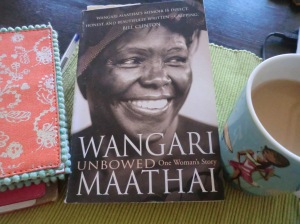

Wangari Maathai was an exceptionally hard working, charismatic, altruist, who came from humble rural beginnings, toiling the land barehanded from a young age to become one of a group of young Africans identified as part of the “Kennedy Airlift”, provided the opportunity to gain bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the US, then completing a PhD in her native Kenya and using her education to work for the betterment of her country and people in terms of sustainable environmental practices social justice.

Wangari Maathai was an exceptionally hard working, charismatic, altruist, who came from humble rural beginnings, toiling the land barehanded from a young age to become one of a group of young Africans identified as part of the “Kennedy Airlift”, provided the opportunity to gain bachelor’s and master’s degrees in the US, then completing a PhD in her native Kenya and using her education to work for the betterment of her country and people in terms of sustainable environmental practices social justice.

In addition to a senior role as a scientist and researcher at a university in Nairobi, needing to do something practical and far-reaching, she founded the sustainable tree planting initiative, The Green Belt Movement and would go on to become a responsible and practically minded activist, working to protect the natural resources and people of Kenya, through her knowledge of where to apply pressure, through her strong international network and above all the high regard in which she was esteemed by many, though sadly, that didn’t include the government of Kenya, who over many, many years continued to block her, plant obstacles in her way, arrest her and make it very difficult for her to continue in her role as an academic and to run her own business.

Wangari Maathai possessed a spirit that refused to lie down, with every setback, she gathered herself and whatever limited resources she still had, and at times this was nearly nothing and always looked towards the one step she could take, that first step towards a solution.

Planting a tree was both symbolic and life-sustaining. As more and more of Kenya’s forest was being deforested, underground water sources were drying up, land that had been planted with indigenous trees was being replaced with cash crops like tea and coffee, stripping the soil of nutrients and occupying land previously used to produce traditional foods for people to eat. As a consequence women began to feed their families more processed foods, requiring less energy to produce, less firewood and increasing the incidence of malnutrition.

“While I was in the rural areas outside Nairobi, I noticed that the rivers would rush down hillsides and along paths and roads when it rained, and that they would be muddy with silt. This was very different from when I was growing up. “That is soil erosion,” I remember thinking to myself. “We must do something about that.” I also observed that the cows were so skinny that I could count their ribs. There was little grass or other fodder for them to eat where they grazed, and during the dry season much of the grass lacked nutrients.”

And she took people with her, she made them part of the solution. To grow The Green Belt Movement required a large network of people to plant trees and to source and nurture seedlings. She went to the women, women like herself who grew up with their hands in the earth, she empowered them to create nurseries in their villages and tend the small trees and keep planting.

“Although the leadership of the NCWK (National Council of Women of Kenya) was generally elite and urban, we were concerned with the social and economic status of the majority of our members, who were poor, rural women. We worried about their access to clean water, and firewood, how they would feed their children, pay their school fees, and afford clothing, and we wondered what we could do to ease their burdens. We had a choice: we could either sit in an ivory tower wondering how so many people could be so poor and not be working to change their situation, or we could try to help them escape the vicious cycle they found themselves in. This was not a remote problem for us. The rural areas were where our mothers and sisters still lived. We owed it to them to do all we could.”

These women were already farmers, they knew how to nurture beans, maize and millet seeds, and Wangari and her team reminded them, they didn’t need a diploma to plant a tree. All they needed was their “women-sense”. These women succeeded, they showed other women what to do and became known as their “foresters without diplomas”. At every stage they looked to see if they could improve the way they did things and to overcome any obstacles the women encountered. It was a huge and sustainable success.

Unfortunately, the government for much of the 80’s and 90’s was against her, almost as if it were a personal affront, to witness a woman speak out and lead and inspire others to stand up to authority; Wangari Maathai was an advocate for proper governance and management of public resources and as soon as she heard about abuses of powers that threatened to remove public rights, she moved her supporters to action.

Through perseverance she won many battles, to save the last big public park in the middle of Nairobi, Uhuru Park from urban development, preventing Karura Forest from being given to friends and political supporters of politicians, the release of political prisoners and even the lobbying of the World Bank to forgive Kenya’s national debt which had escalated out of control. due to interest payments, despite the original loan amounts having been repaid .

“When I see Uhuru Park and contemplate its meaning, I feel compelled to fight for it so that my grandchildren may share that dream and that joy of freedom as they one day walk there.”

Unbowed, One Woman’s Story, is an astonishing and important recollection of the life and work of Wangari Maathai. She applied herself to everything she did with vigour and heart, the opportunity to be educated, something that continues to be lobbied for so many girls in third world countries, was a major turning point and became the first of many open doorways she walked through and made the most of, not for own benefit, but always for the good of all.

It seems almost like a utopian fantasy, to imagine what the world could be like, if more women were given the opportunity to gain the necessary knowledge that could allow them to facilitate solutions to village and country problems, that allowed them to live sustainably and not in fear or poverty without understanding why. Wangari Maathai knew and practised that one person can’t change everything, it is through showing and empowering others that change happens.

She was an amazing, inspirational and practical woman, who responded to the call for help on many significant issues that would benefit all Kenyan’s and was an example to the world, rightfully acknowledged and awarded the Nobel Prize for peace in 2004. Sadly she passed away in 2011 from ovarian cancer.

“Throughout my life, I have never stopped to strategize about my next steps. I often just keep walking along, through whichever door opens. I have been on a journey and this journey has never stopped. When the journey is acknowledged and sustained by those I work with, they are a source of inspiration, energy and encouragement. They are the reasons I kept walking, and will keep walking, as long as my knees hold out.”

Wangari tells a wonderful story of how the hummingbird responds to a forest fire, in a delightful metaphor that describes exactly her attitude to life and the many challenges that surround us. It has been made into a 2 minute animated film, Dirt, narrated by Wangari Maathai and is a wonderful introduction to her faithful, persevering spirit. A wonderful short film and one of my Top Reads for 2015.

I will be the hummingbird…