Stunning.

I thought The Forbidden Notebook which I read in 2023 was excellent, but this novel is in a category of its own. This is probably the title in 2024 I was looking forward to the most and it exceeded my expectations.

Originally published in Italian in 1949 as Dalla parte de lei, this captivating new English translation by Jill Foulston was published by Pushkin Press in 2024.

Women’s Partisan Struggle in 1930’s -1940’s Italy

Alba de Céspedes (1911-1997) was a bestselling Italian-Cuban novelist, poet and screenwriter who worked as a journalist throughout the 1930’s while also taking an active part in the Italian partisan struggle and was twice jailed for her anti-fascist activities.

After the fall of fascism – Rome, considered the heart of fascism under Mussolini, was liberated in June 1944 and many felt the country had lost its basic values after 20 years of fascist government – Alba de Céspedes founded a literary journal called Mercurio, publishing many great names of Italian literature and politics, as well as Katherine Mansfield, Jean-Paul Satre, Ernest Hemingway.

Due to a lack of funding it would close in 1948, and in its final issue she published an essay by Natalia Ginzburg entitled ‘On Woman’, alongside a letter she was inspired to write in response to it. Certainly, she would have been working on the novel Her Side of The Story, at the time this essay (discussed below), was published.

Women Writing From the ‘Well’

Ginzburg had written of an affliction unique to women – at a time when they were often confined to the home and not considered equal under the law – that she described as “a continuous falling down a deep dark well“, a terrible melancholy typical of feminine disposition that likely originated from the age-long tradition of subjection and subjugation.

In her open letter, de Céspedes confesses that she also writes from the ‘well’ Ginzburg theorises. Despite that, de Céspedes believed women’s freedom consisted of being able to go down those emotional and psychological wells, which were for her a strength, rather than a curse. ‘Every time we fall down a well’, de Céspedes wrote, ‘we descend to the deepest roots of our being human; when we come back to the surface, we carry such experiences with us that enable us to understand everything men never will — since they never fall into any well’.

In the same issue of Mercurio, de Céspedes published La donna magistrato’ (‘The Woman Magistrate’), an essay by Maria Bassino, one of the most important criminal defense lawyers at the time, addressing women’s rights to become magistrates. In her letter to Ginzburg, de Céspedes explained that those two essays were published together to denounce the injustice done to women when they were tried by magistrates who cannot understand women’s reasons to ‘kill, steal, and commit other humiliating actions’; referring to men who never experienced the depth of wells.

If we are not sure of the depth and character of the mid twentieth century well, then by the time we finish reading Her Side of The Story, we most certainly have a greater understanding of it.

The Review: Her Side of the Story

An expansive coming of age tale of love and resistance, this feminist, social novel explores a young woman’s attempt to break free from society’s expectations and live life on her own terms. Amid great storytelling, it is a fearless condemnation of patriarchy and rejection of fascist ideals in a society on the cusp of witnessing social change for women.

Alessandra grows up in a bustling apartment block in 1930’s Rome with a shared courtyard, where everyone knows everyone, spending most of her time alone in the apartment in the care of Sista, while her father is at his office and her mother is out teaching piano lessons. She adores her quiet, delicate mother, who keeps to herself and treats her daughter like a friend, while despising a father she believes doesn’t deserve an elegant, cultured woman like her mother.

The women felt at ease in the courtyard, with the familiarity that unites people in a boarding school or a prison. That sort of confidence, however, sprang not so much from living under a common roof as from shared knowledge of the harsh lives they lived: though unaware of it, they felt bound by an affectionate tolerance born of difficulty, deprivation, and habit. Away from the male gaze, they were able to demonstrate who they really were, with no need to play out some tedious farce.

Alessandra looks back and recounts her childhood, adolescence and marriage, describing her experience of them all, her inner world view and how it was shaped by what she observed happening around her, everything she thought and how she responded to it all.

Though she spends much time alone, she rarely keeps her thoughts to herself, allowing the deepest parts of herself to be exposed, challenging what she does not agree with, determined to take charge of her life and live it according to her own desire, against convention.

A Rare and Faultless Admiration of Mother

The first section is focused on the mother-daughter relationship, on Alessandra’s blind faith in everything her mother is and does, including her obsession with the Pierce family, their friendship with Lydia and her daughter Fulvia upstairs and sessions with the medium Ottavia who visits the apartment block on Fridays. Invited to play at a private concert with the Pierce son Hervey joining on violin, the celebratory event witnessed by her husband, becomes a turning point.

The depictions of life in the apartments, the details of the women’s lives, the absent husbands, the affairs, the way daughter’s follow mother’s examples, the witnessing of each other’s lives, the door porter who sees and knows all, the desire for privacy and impossibility of it are all brilliantly depicted. Alessandra’s mother is a romantic with dignity, she is not interested in an affair, but is vulnerable to kind attention.

After a near expulsion from school for hitting a boy for his psychological cruelty towards another girl, she confesses what happened to her mother and worries about her father’s response.

“We can’t tell him everything. Men don’t understand these things Sandi. They don’t weigh every word or gesture; they look for concrete facts. And women are always in the wrong when they come up against concrete facts. It’s not their fault. We’re on two different planets; and each one rotates on its own axis – inevitably. There are a few brief encounters – seconds, perhaps – after which each person returns to shut him- or herself away in solitude.”

Alessandra spends a lot of time reflecting, examining the depths of her thoughts, actions and observations and how they may have come about. From her parents certainly, but she recognises something restless in herself, that seeks retribution.

I could reproach her for having subjected me to that climate of perpetual exaltation, which, above all, made me completely devoted to the myth of the Great Love and thus unintentionally led to the painful situation I find myself in today. I could reproach her, perhaps, if she hadn’t already paid for her ambitions. And now that I am forced to write about her and look into the most intimate and dramatic moments of our life together, it’s not really to accuse her of having made me what I am but to explain those of my actions which would otherwise be clear only to me.

Allesandra, sono io, I am Alessandra

It is Sandi’s story but it is also the story of many ordinary lives of girls and women, growing up in discordant families, with the weight of expectations, the allure and (false) promise of love, the desire to be educated, to participate in something greater than ‘the home‘, to be heard, respected and taken seriously.

“…Alba de Céspedes intended to act as the defender of women. Like Flaubert, she could say of her protagonist: Alessandra, sono io, I am Alessandra.

Rural Idealism Enforced by The Matriarch

In the second section, Alessandra is sent to live on a farm with her paternal grandmother Nonna, a grand matriarch of a traditional, religious family who surround her with examples of duties expected of her and demonstrate how they will act to facilitate them. She enjoys the natural environment and complies to a certain point, but insists on her right to further her studies, rejecting the suggestion of a well aligned matrimony.

Though this section was originally cut from the first English translation (1952) of the novel, it is restored here. The rural setting represents tradition and a connection to the land, the roots of family, hard work and lineage. Mussolini’s regime focused on rural regions to uphold goals of self-sufficiency, free Italy from “the slavery of foreign bread” and control the agricultural sector. Propaganda praised this lifestyle, much of it targeted at women and upheld by women. Nonna exemplifies and encourages the virtues of sacrifice for the greater good and giving up one’s selfish desires.

Bewildered, I observed these grave, taciturn people who had been strangers to me a few hours before, but who now embraced me within a mechanism so robust I sensed it could easily overwhelm a person.

War breaks out, she returns to Rome, to her studies, to employment, to living again with her father and meeting Francesco, the man she would truly love and believe she could have a different kind of life with. And it might be said that that is where her troubles really begin.

Love, Marriage, War – the struggle

There is so much that could be said about Alessandra’s wartime and matrimonial experience, that is better left for the reader to discover.

There is no stone left unturned in her dissection of the relationship she has with the older anti-fascist Professor, a charismatic man with a sense of justice who stands up for his beliefs, the only man she will ever truly love and her attempts to talk to him about the things that unsettle her, that she feels could be easily resolved, if only he took the time to listen. Once married, he is barely aware of or able to respond to her feelings, while she continues to try to make him understand, slowly unravelling in her persistent attempt.

The most misleading virtue of marriage is the ease with which one forgets, in the morning, everything that happened the night before. Encouraged by the clear colour of the sun’s first rays and the energy and rhythm of everyday gestures, I was always the first to turn back towards Francesco.

The novel tracks the attempt to rise above expectation and the subsequent decline into acceptance, focusing on the effect of this repression, the mental deterioration of generations of women for whom the burden of that ordinary life, of a woman’s limited lot, and the inaccessibility of how (here) she imagines it might have been, become too much to bear. She wants the reader to understand this very well, effectively making you live it alongside her.

Intense, compelling and set against that backdrop of wartime Rome and Italy coming out of a long repressed fascist era, I found it utterly riveting. Her Side of the Story is a powerful, intimate and insightful exploration of the female psyche, of the desire to be, and do, more than meet long outdated representations of women in families, society and relationships. Unputdownable, one of the best of 2024 for sure. Fans of Natalia Ginzburg and Elena Ferrante will likely enjoy this. Expect to feel unsettled.

There’s No Turning Back

Delighted to learn that her debut novel There’s No Turning Back translated by Ann Goldstein will be published in February 2025.

Highly Recommended.

Further Reading

Natalia Ginzburg’s essay ‘Discorso sulle donne’ ‘On Women’ translated by Nicoletta Asciuto, The Fortnightly Review

Jacqui’s Review at JaquiWine’s Journal, April 2024

Chicago Review of Books: The Prescience of Alba De Céspedes’s “Her Side of The Story” by Margarita Diaz November 24, 2023

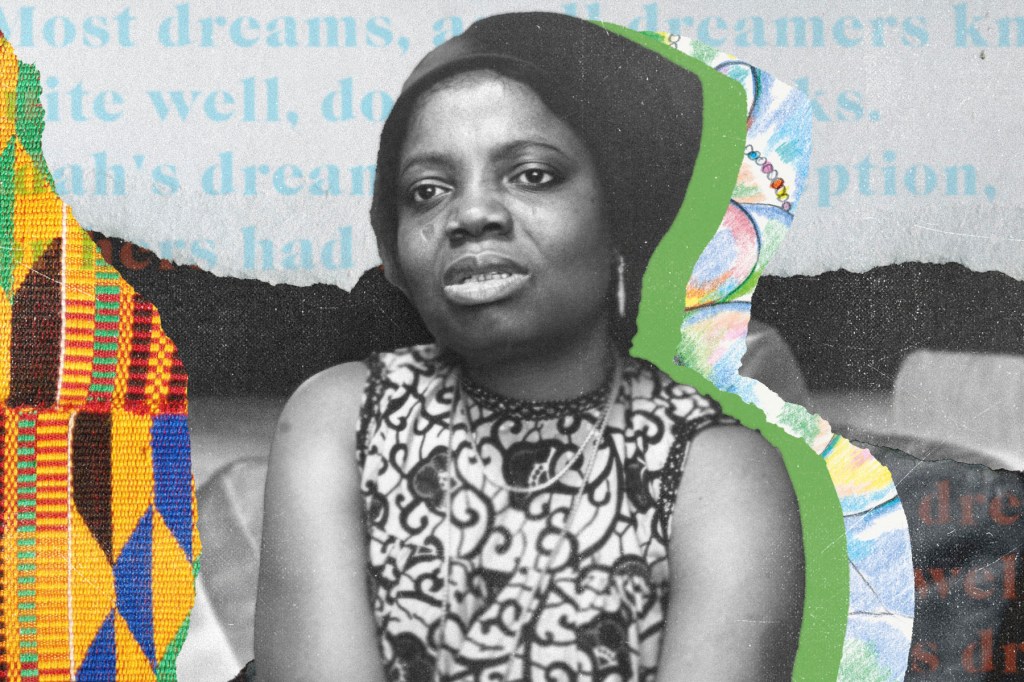

Author, Alba de Céspedes

Alba de Céspedes (1911-97) was a bestselling Italian-Cuban novelist, poet and screenwriter.

The granddaughter of the first President of Cuba, de Céspedes was raised in Rome. Married at 15 and a mother by 16, she began her writing career after her divorce at the age of 20. She worked as a journalist throughout the 1930s while also taking an active part in the Italian partisan struggle, and was twice jailed for her anti-fascist activities. After the fall of fascism, she founded the literary journal Mercurio and went on to become one of Italy’s most successful and most widely translated authors.

After the war, she accompanied her husband, a diplomat to the United States and the Soviet Union. She would later move to Paris, where she would publish her last two books in French and where she spent the rest of her life. She died in 1997.