This is a raw, visceral read and I’m glad I read it in a group discussion. First published in 1975 and edited by Toni Morrison, it was Gayl Jone’s debut novel.

Written when the author was 26 years old, a similar age to her young protagonist Ursa Corrie (Corregidora) when we first encounter her. Ursa sings blues in a bar, the first paragraph of the book, reads like a piece of flash fiction, a story in 150 words. Of her marriage to Mutt in Dec 1947, his dislike of her singing after their marriage because he believed marriage changed all that.

Written when the author was 26 years old, a similar age to her young protagonist Ursa Corrie (Corregidora) when we first encounter her. Ursa sings blues in a bar, the first paragraph of the book, reads like a piece of flash fiction, a story in 150 words. Of her marriage to Mutt in Dec 1947, his dislike of her singing after their marriage because he believed marriage changed all that.

“I said I sang because it was something I had to do.”

And in April 1948 after threatening publicly to remove her from the stage, other men throw him out, but he is there waiting for her outside at the end, after that evening her short-lived marriage is over and another man waits for her.

Much of the novel is relayed in dialogue and in sections that reconnect with the past, with things her mother told her, that her grandmother has said to her, and conversations that took place between the grandmother and the great grandmother that Ursa asks her mother about. She visits her mother to ask more about the unsaid.

She sat with her hands on the table.

‘It’s good to see you, baby,’ she said again.

I looked away. It was almost like I was realizing for the first time how lonely it must be for her with them gone, and that maybe she was even making a plea for me to come back and be a part of what wasn’t anymore.

There are things she wants to know, an oral history that is supposed to be passed down to protect them, however there are subjects her mother hasn’t opened up about. About Corregidora, a 19th century slavemaster who fathered both her mother and grandmother. And who her father was.

‘He made them make love to anyone, so they couldn’t love anyone.’

Photo by cottonbro on Pexels.com

Ursa feels those things in her, the inherited trauma, but doesn’t understand it. We witness her reactions to things, the duality of her strength at standing up for herself alongside her inability to speak at all.

She has both strength and reticence.

The attack by her husband landed her in hospital, and resulted in doctors removing her womb, the forced sterilisation of Black women part of America’s eugenics policy at the time. This causes Ursa to reflect on the broken line, the passing down of the oral history, the need to ‘create generations’. What is her place now that she is the end of a lineage.

But I am different now, I was thinking. I have everything they had, except the generations. I can’t make generations. And even if I still had my womb, even if the first baby had come – what would I have done then? Would I have kept it? Would I have been like her, or them?

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

Trauma experienced pre-conception changes a persons DNA and is passed on. It need not be explained, it is most often not understood, it is lived out through experiences and reactions to them. Present from conception, inherited without notice, it is no wonder that children who inherit both the trauma of the victim (slave or slave descendant) and the DNA of the perpetrator (slave master) are confused, both one thing and its opposite, neither nor, either or.

It was as if she had more than learned it off by heart, though. It was as if their memory, the memory of all the Corregidora women, was her memory too, as strong with her as her own private memory, or almost as strong. But now she was Mama again.

As James Baldwin put it,

“it dares to confront the absolute terror which lives at the heart of love”

Further Reading

Virago Press: Where To Start With Gayl Jones

Article, New Yorker: Gayl Jones’s Novels of Oppression by Hilton Als

Article, The Atlantic: The Best American Novelist Whose Name You May Not Know by Calvin Baker

Essay, New York Times: She Changed Black Literature Forever. Then She Disappeared. In Search of Gayl Jones, whose new novel breaks 22 years of silence by Imani Perry.

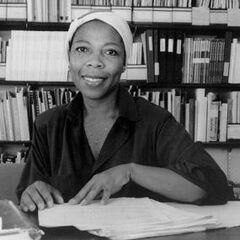

Gayl Jones, Author

Gayl Jones was born in Kentucky in 1949. She attended Connecticut College and Brown University. She is a novelist, poet playwright, professor and literary critic.

Gayl Jones was born in Kentucky in 1949. She attended Connecticut College and Brown University. She is a novelist, poet playwright, professor and literary critic.

She wrote Corregidora (1975), Eva’s Man (1976), and The Healing (1998) which have all recently been republished as Virago Modern Classics.

The Healing was a fiction finalist for the National Book Awards in 1988.

Her most recent and long awaited novel is Palmares (2021).

Potiki is the story of a family and the encroachment on their lives of the now dominant culture that is trying to usurp their way of life, a land developer wants to turn their coastal ancestral land into a holiday park, and will use whatever tactics necessary to do it.

Potiki is the story of a family and the encroachment on their lives of the now dominant culture that is trying to usurp their way of life, a land developer wants to turn their coastal ancestral land into a holiday park, and will use whatever tactics necessary to do it. Their home, their land and community is under threat from outsiders, who covet their location and do everything they can to entice them to give it up, to sell, using the offer of money, then more threatening measures to get what they want.

Their home, their land and community is under threat from outsiders, who covet their location and do everything they can to entice them to give it up, to sell, using the offer of money, then more threatening measures to get what they want. Book Review

Book Review Irene has strong and angry thoughts on Claire’s predicament, but in her presence is unable to act in accordance with them. She is stuck between loyalty to her race and guilt at her ability to pass for the thing that so oppresses them.

Irene has strong and angry thoughts on Claire’s predicament, but in her presence is unable to act in accordance with them. She is stuck between loyalty to her race and guilt at her ability to pass for the thing that so oppresses them. Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont was named by the Guardian as one of ‘the 100 best novels,‘ and shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1971. It is a humorous and compassionate look at friendship between an old woman and a young man at a time in her life when she has little to look forward to.

Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont was named by the Guardian as one of ‘the 100 best novels,‘ and shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1971. It is a humorous and compassionate look at friendship between an old woman and a young man at a time in her life when she has little to look forward to.

Jean Rhys was born in the Caribbean island of Dominica in 1890, the daughter of a Welsh doctor and a third generation white Creole mother of Scots origin (‘Creole’ was broadly used to refer to any person born on the island, whether of white or mixed blood). When she was sixteen she was sent to England to school, mocked due to her accent, left and became a chorus girl. After a disastrous affair and disillusioned by events, she began to write, fictionalising many of her experiences and thanks to finding a mentor in Ford Maddox Ford, found moderate success.

Jean Rhys was born in the Caribbean island of Dominica in 1890, the daughter of a Welsh doctor and a third generation white Creole mother of Scots origin (‘Creole’ was broadly used to refer to any person born on the island, whether of white or mixed blood). When she was sixteen she was sent to England to school, mocked due to her accent, left and became a chorus girl. After a disastrous affair and disillusioned by events, she began to write, fictionalising many of her experiences and thanks to finding a mentor in Ford Maddox Ford, found moderate success.