I really enjoyed Passing, but I might be in the minority when I say I loved Quicksand which I read first, even more. Quicksand adds into its complexity that little known element of being a TCK (third culture kid), Helga is not only of mixed race, but she was born and is growing up in a culture (America) that neither of her parents were born into or belonged to, there is no extended family for her to mould into, whereas in Passing, we meet two women who have a stronger sense of family and there is more of a focus on belonging to a race and by extension, its culture.

Book Review

Book Review

In Passing, we meet Irene who has just received a letter from an old friend, one who twice in her life she believed she would never see again and with distaste realises this letter is evidence of her reappearance in her life. Intending to resist seeing her, she ignores it.

The narrative then goes back in time to the earlier encounter when Irene was visiting Chicago where her parents live, doing last minute shopping for her children, overcome by the heat, she hails a cab and asks the driver to take her to a rooftop hotel. It is here that Irene practices her version of ‘passing’ as a white bourgeoise person, alone, unobserved, quietly taking tea by a window where no one is near, a moment to recuperate.

“It’s funny about ‘passing’. We disapprove of it and at the same time condone it. It excites our contempt and yet we rather admire it. We shy away from it with an odd kind of revulsion, but we protect it.”

To her horror, a man and woman appear and take the table next to her. The man leaves and the woman stares at her in an unsettling manner. Fear pervades her as the woman approaches, recognising her.

“About her clung that dim suggestion of polite insolence with which a few women are born and which some acquire with the coming of riches or importance.”

Passing is taut with tension beginning with this scene, Irene is careful, her old school friend Clare takes what to Irene are unbearable risks, something she wants to distance herself from, doing all she can not to fall into her manipulative ways. But her charm is near impossible to resist, she is more practiced in passing and in getting what she wants, in ways Irene wouldn’t dare imagine.

Irene has strong and angry thoughts on Claire’s predicament, but in her presence is unable to act in accordance with them. She is stuck between loyalty to her race and guilt at her ability to pass for the thing that so oppresses them.

Irene has strong and angry thoughts on Claire’s predicament, but in her presence is unable to act in accordance with them. She is stuck between loyalty to her race and guilt at her ability to pass for the thing that so oppresses them.

“Mingled with her disbelief and resentment was another feeling, a question. Why hadn’t she spoken that day? Why, in the face of Bellew’s ignorant hate and aversion, had she concealed her own origin? What had she allowed him to make his assertions and express his misconceptions undisputed?”

The fear Irene has turns it into something of a psychological suspense novel, use of the word dangerous planting the seed of it early on.

“Her brows came together in a tiny frown. The frown, however, was more from perplexity than from annoyance; though there was in her thoughts an element of both. She was wholly unable to comprehend such an attitude towards danger as she was sure the letter’s contents would reveal; and she disliked the idea of opening and reading it.”

Neither woman is totally content with the life decisions they have made, each of them reaching for something that eludes now them, witnessing it in the other, living with a pervasive level of anxiety that threatens to disrupt their lives. Their predicaments provide an insight into the country’s turbulent feelings towards integration and race relations in the 1920 -1930’s

Further Reading

My review of Quicksand by Nella Larsen

My review of From Caucasia With Love by Danza Senna

Lapham’s Quarterly: Passing Through by Michelle Dean: Nella Larsen made a career of not quite belonging

Essay in Electric Literature by Emily Bernard: In Nella Larsen’s ‘Passing,’ Whiteness Isn’t Just About Race

New York Times: Overlooked Obituaries – Nella Larsen (1891-1964) Harlem Renaissance-era writer whose heritage

informed her modernist take on the topic of race by Bonnie Wertheim

Harlem Renaissance Titles Reviewed Here

Not Without Laughter by Langston Hughes

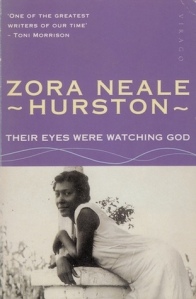

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde

Not Without Laughter is a coming-of-age story that introduces us to Sandy Rogers who lives with his grandmother who everyone refers to as Aunt Hager and his mother Annjee, who works as a housekeeper for a rich white family, while his father Jimboy traverses the country pursuing a living as a musician.

Not Without Laughter is a coming-of-age story that introduces us to Sandy Rogers who lives with his grandmother who everyone refers to as Aunt Hager and his mother Annjee, who works as a housekeeper for a rich white family, while his father Jimboy traverses the country pursuing a living as a musician.

If you have read or were considering reading Marlon James Booker winning

If you have read or were considering reading Marlon James Booker winning  Unable to protect her daughter, who was raped by her schoolteacher, her focus moves to Janie, whom the daughter leaves her with. As soon as adolescence beckons she arranges for her to marry an older farmer with land. Janie dreams of love and fulfilment and when mentions not finding it in this marriage is reprimanded by her grandmother for her romantic notions.

Unable to protect her daughter, who was raped by her schoolteacher, her focus moves to Janie, whom the daughter leaves her with. As soon as adolescence beckons she arranges for her to marry an older farmer with land. Janie dreams of love and fulfilment and when mentions not finding it in this marriage is reprimanded by her grandmother for her romantic notions.