Apaprt from committing to read Women in Translation in August, I read less consciously and more by mood or whatever stood out on the shelf this year.

Though I read more books, I read from the same number of countries, but less in translation. In 2024, 33% (20 books) of the titles I read were in translation – a conscious effort. This year only 15%. It is also in part the effect of taking a subscription, I loved most of the Charco Press titles I read, but there were some I was less inclined to read; I would look at them and then choose something else.

It’s about discernment. So I remove those books from the shelf and more carefully research those I have no hesitation in wanting to read. I chose well this summer and so I here are the best seven titles I highly recommend. I’ll be making a more conscious effort to read more in translation in 2026, so please share with me your favorites from this year.

Top 7 Reads in Translation

The Runner Up Outstanding Read of 2025

Somebody is Walking On Your Grave: My Cemetery Journeys, Mariana Enriquez (Argentina) tr. Megan McDowell

See yesterday’s post Runner Up for Outstanding Book of the Year. The author travels to 13 countries over two decades, visiting cemeteries – mixing travelogue, personal history, cultural history and collective memory. I read the essays over a month, each one exhibiting not just the protocols around death, but the context of different eras that each country has been through, and how that has impacted the collective memory. Her essays take the reader to :

Europe: Italy, Spain, France, United Kingdom (England & Scotland), Czech Republic, Germany

Americas: Argentina, Chile, Mexico, United States, Peru, Cuba

Oceania: Australia

Argentina in the ’70s, the decade where I was born, had a dictatorship that made a lot of bodies disappear. Therefore, there’s a generation of people that were killed by the government, and they don’t have a grave.

I realized that that trauma, that is very engraved in my life, somehow made me feel that a grave, a tombstone – it’s something of comfort. It’s a final thing in a good way.

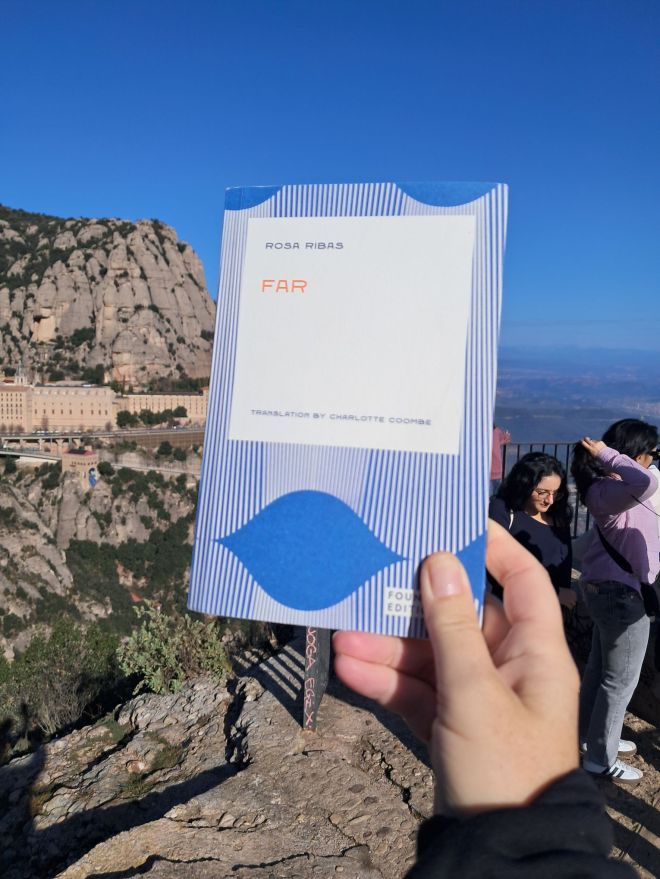

Far by Rosa Riba (Spain) tr. Charlotte Coombe

Far was a novel I came across by the relatively new publisher of Mediterranean literature, Foundry Editions after reading an article in the Guardian about a building project in Spain, 13,500 affordable apartments built to house 40,000 people, a ghost town after the global financial crisis, and the deepest economic recession Spain had experienced for fifty years.

Author Rosa Ribas was taken by friends to visit this strange monument to a broken era in Seseña; the housing development was known as ‘The Manhattan of La Mancha’ and as night fell three lights came on and inspired an idea for her novel Far, a story of determined inhabitants trying to create community, while others are escaping who knows what? We follow two characters, both dealing with issues, one in hiding, the other part of the community. Tensions rise, the locals become paranoid and angry at their untenable situation, mirroring the disintegration of the country’s economic situation, disenfranchised youth and a rise in racism and xenophobia.

The entire development was constructed on a pile of poorly concealed sleaze, a chain of bribery, corruption, intimidation, and complicit silences. No ancient manuscripts, no mythical foundations. If these lands had been the scene of some momentous event, back when battles of conquest and reconquest were being fought all over the area, no one had bothered to record it. It was a bleak place, devoid of stories, where it was impossible to satisfy any yearnings for greatness.

The Body Where I Was Born by Guadalupe Nettel (Mexico) tr. J.T. Lichenstein

Having loved Still Born by the same author, I picked this up and was equally mesmerised. This novel is a semi-autobiographical coming of age story set in the 1970’s, that follows a girl’s childhood in Mexico, the things that marked her experience, that she looks back on now (from a therapist’s chair) with a better understanding of the impact.

She ponders the harm of parental regimes and how they perpetuate onto the next generation the neuroses of one’s forebears, in her case her parents were ‘open-minded’ in a way that ultimately lead to the disintegration of the family and a period of living with a grandmother who disliked her. She and her brother then move to the south of France while her mother pursues studies and a new love.

Enjoying it, I was surprised to learn the narrative moved to the same town where I live. The siblings navigate life at a local school among pupils from multiple origins, North African, Indian, Asian, Caribbean and French, a unique and unforgettable experience, very much unlike the international schools they had attended elsewhere.

It is an engaging, insightful recollection of an atypical upbringing, within different cultures. Loved it!

To survive in this climate, I had to adapt my vocabulary to the local argot – a mix of Arabic and Southern French – that was spoken around me, and my mannerisms to those of the lords of the cantine.

All That Remains by Virginie Grimaldi (France) tr. by Hildegarde Serle (French)

Another book set in France, this time set in Paris, this a page turner from the opening chapters, a feel good novel and another that I was attracted to due to its connection to real life events. I had heard about elderly widowed Parisians in largish apartments being assisted by a specialist agency that matched them with mature students as a way to keep them in their own homes, and to provide students with accomodation.

This is the premise of the novel; recently widowed Jeanne (74) decides to rent one of her rooms and two people quickly respond, an 18 year old Théo, apprentice boulanger, of no fixed abode and a thirty something Iris, who is escaping from something. It’s a perfect slice of ordinary life in Paris and a wonderful example of a new way to live, where young and old help each out and all the better for it.

“Hello Madame, I just wanted to confirm my interest in your room for rent. And please know that, if it weren’t for my tricky situation, I’d never have interrupted your conversation with the young man, who also seems in real need of a home. If you’ve not yet made your choice, I’d understand if you favour him. Regards Iris.”

The Brittle Age (L’età fragile) by Donatella Di Pietrantonio (Italy) tr. Ann Goldstein

Winner of the 2024 Strega Prize, The Brittle Age is a novella inspired by an historic true-crime event in the 1990’s, a double femicide in the mountainous region of the Abruzzo Apennines in Italy, a novel dedicated to “all the women who survive”. The third novel I’ve enjoyed by her, since A Girl Returned and A Sister’s Story.

Though it is framed by an actual event, this novel really piqued my interest for the way it dealt with the mother-daughter relationship. Lucia’s daughter Amanda returns from Milan on one of the last trains as the pandemic shuts everything down, she stays in her room, barely eats, doesn’t talk, her phone lies uncharged under the bed. Lucia worries but can get nothing out of her.

The novel explores both the events of the past and the mother’s struggle to understand what is going on with her daughter. Amanda’s reclusiveness awakens memories and feelings Lucia has suppressed from 30 years ago. Although the story is about a crime, the mystery of what happens sits alongside the portrait of a fractured family and community, all impacted by the past, burying it with silence. I loved the balance of revelations of both past events and present predicaments, a most memorable read.

Our birthplace had protected us for a long time, or maybe that had been a false impression. We grew up in a single night.

All Our Yesterdays, Natalia Ginzburg (Italy) tr. Angus Davidson, Intro Sally Rooney

This might be my favourite Natalia Ginzburg novel – it sits alongside her family memoir Family Lexicon and often reminded me of parts of that book, clearly inspired by events she lived through.

Set in Northern Italy in the lead up to WWII, the war era through to liberated, it is a brilliant depiction of two Italian families (one family own the leather factory in town, the other is middle class), neighbours who live opposite each and everyone they’re connected to, everyone who enters their home – what they live through during this era, how they keep tabs on each other, the dilemmas they face, how they deal with them, their tragedies and accomplishments, their loves and losses.

The absence of the mother, and the ill health of their authoritarian father, intent on writing a memoir critical of the regime, looms over them and creates tension and an air of rebellion. Youth desire change and autonomy in a country that feels increasingly oppressive leading them towards risk and turbulent decisions.

This story and its characters was so immersive, and the depiction of difficult times treated with compassion, as we encounter each event, every friend or person connected to those two households. When not present they are the subject of letters, so at almost all times everyone is aware of the well-being of the others. In the second part of the novel, the focus shifts to the impoverished rural Italian south

It was so, so good, it really gives a sense of what it was like to live through this period for this family, especially knowing the hardship the author lived through, her young, anti-fascist husband Leone was tortured and murdered by the Gestapo.

This was a war in which no one would win or lose, in the end it would be seen that everyone had more or less lost.

Brandy Sour by Constantia Soteriou (Cyprus) tr. Lina Protopapa (Greek)

Another favourite from Foundry Editions, this is a wonderful novella that is like a series of vignettes set in an old hotel in Cyprus, each one from the perspective of a character with a connection to the hotel, their story told through a tale related to a particular beverage and often how it cures them of various afflictions. Clever but simplistic and there are threads that carry through making it read more like an interconnected story than separate stories.

He always wakes at dawn and he goes to the kitchen to have his coffee prepared the way he likes it. The only coffee of the day. With lots of kaymak and no sugar. Turkish coffee – Greek coffee, he always corrects himself – with sugar is an absolute waste of coffee. It needs to be bitter. There’s no point otherwise.

The emblematic Ledra Palace Hotel was established in 1949 on Nicosia’s UN-controlled buffer zone, the Green Line that, since 1964, has divided the island into Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot sectors and reading the book one discovers a little known history of the island and its people, those who visited int he past, from colonial visitors to the Egyptian King, employees, local villagers.

“The Palace was the epicentre of the island’s recent history. It was built as the promise of a new era; a haven for all nationalities, all communities. It drew people from all backgrounds: the wealthy bourgeoisie who lounged by its cerulean pool; the poorer working classes who made its beds – and its Brandy Sours…”

* * * * * *

That’s it for 2025. Let me know what works in translation were your favourites this year. Thanks for reading and sharing and commenting. Happy Reading!

At only 76 pages, it is a brief recollection that begins in quiet, dramatic form as she recalls the day her father, at the age of 67, unexpectedly, quite suddenly dies.

At only 76 pages, it is a brief recollection that begins in quiet, dramatic form as she recalls the day her father, at the age of 67, unexpectedly, quite suddenly dies. Ernaux’s father was fortunate to remain in education until the age of 12, when he was hauled out to take up the role of milking cows. He didn’t mind working as a farmhand. Weekend mass, dancing at the village fetes, seeing his friends there. His horizons broadened through the army and after this experience he left farming for the factory and eventually they would buy a cafe/grocery store, a different lifestyle.

Ernaux’s father was fortunate to remain in education until the age of 12, when he was hauled out to take up the role of milking cows. He didn’t mind working as a farmhand. Weekend mass, dancing at the village fetes, seeing his friends there. His horizons broadened through the army and after this experience he left farming for the factory and eventually they would buy a cafe/grocery store, a different lifestyle. Born in 1940,

Born in 1940,  I’ve been aware of The Balkan Trilogy for a while and curious to discover it because of its international setting (Romania in the months leading up to the 2nd World War) though equally wary of English ex-pat protagonists living a life of privilege cosseted alongside a population suffering economic hardship and the imminent threat of being positioned between two untrustworthy powers (Russia and Germany).

I’ve been aware of The Balkan Trilogy for a while and curious to discover it because of its international setting (Romania in the months leading up to the 2nd World War) though equally wary of English ex-pat protagonists living a life of privilege cosseted alongside a population suffering economic hardship and the imminent threat of being positioned between two untrustworthy powers (Russia and Germany). The novel becomes even more interesting and ironic when Guy decides to produce an amateur production of the Shakespearean play Troilus and Cressida, deliberately diverting the attention of his fans and followers, young and old, at a time when war is creeping ever closer and everyone else not involved in his amateur dramatics is frantic with worry. The play is the tragic story of lovers set against the backdrop of war.

The novel becomes even more interesting and ironic when Guy decides to produce an amateur production of the Shakespearean play Troilus and Cressida, deliberately diverting the attention of his fans and followers, young and old, at a time when war is creeping ever closer and everyone else not involved in his amateur dramatics is frantic with worry. The play is the tragic story of lovers set against the backdrop of war.