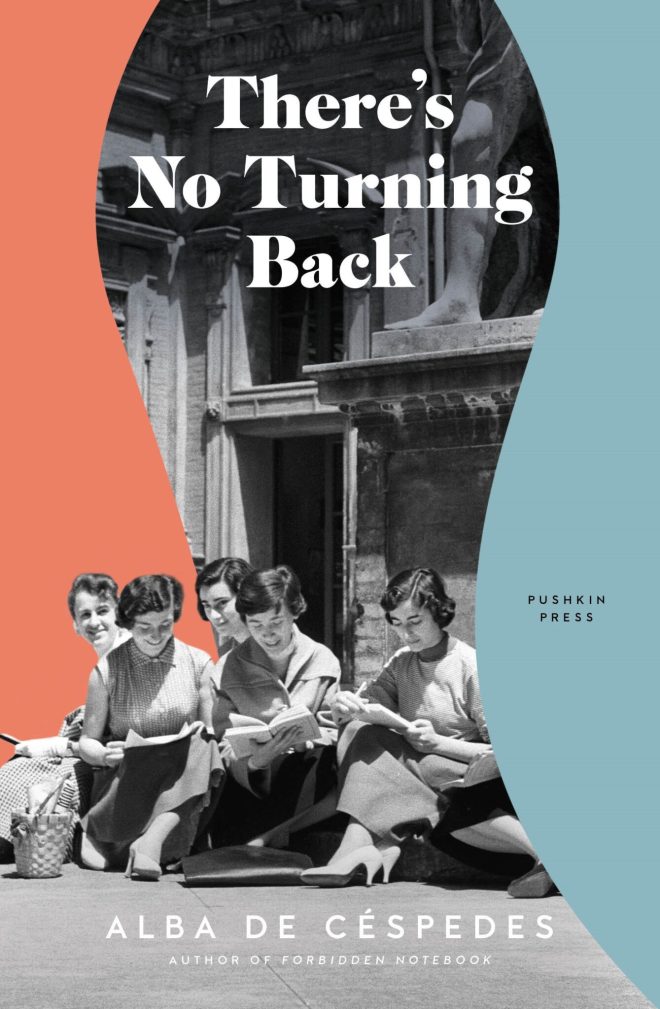

Every novel I’ve read by Alba de Céspedes has been excellent and this controversial debut (at the time of its original publication in Italy, 1938) brims with the seeds of what was to come from her work, starting with this excellent, collective coming-of-age, of eight, twenty-something year old women in pre-war Rome.

I pre-ordered this novel, as she is a favourite author, of whose work I want to read everything, sharing now for WIT Month (Women in Translation).

Literature and Morality

In the informative translator’s note at the beginning of the book, Ann Goldstein shares some of the historical context within which the book became an immediate and immensely popular bestseller, despite the authorities finding the novel’s breaking of female stereotypes and suggestion of other possible pathways for women offensive.

“By the time the novel was published the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini had been in power for more than a decade. His government promoted the idea that the proper place for women was to be at home and to bear children; sposa e madre esemplare (exemplary wife and mother). While there is no overt mention of Mussolini or fascism in the novel, none of the young women conform to this female ideal. In fact, in their different ways they are challenging it, even if not intentionally or even consciously.”

Selected to win the prestigious Viareggio Literary Prize in 1939, a government order stopped it and attempted to block further editions from being published, claiming it went against ‘fascist morality’. As Margarita Diaz points out in a recent article ‘An Immoral Endeavour‘:

Vague accusations of ‘immorality’ have been, and continue to be, used by dominant institutions, governments and autocratic regimes to stifle free expression and to censor legions of books and artworks.

Women at a Turning Point

Set in Rome 1936-1938, the novel focuses on eight young women in higher education, most studying at university, who live together in convent boarding house in Rome. They have greater freedoms than school girls, with restrictions deemed appropriate for unmarried single women.

From different backgrounds they have different issues, desires and ideas about life, which they share with each other as they progress through the year and one by one prepare to leave the premises.

On the cusp of “no turning back”, concluding their theses, each must make a decision about what to do next and none of them are thinking, acting or passively accepting the route that tradition has dictated.

The mere consideration of other life avenues and the outward expression of those thoughts, the girls’ discussions with each other, in this safe and open, female community, demonstrate an important processing step in their being better informed, while equally often challenged by their peers, at this formative moment in their lives.

“In all her novels de Céspedes investigates women’s attempts to both deconstruct and construct their lives and gain a sense of themselves, as she investigated her own life.”

A Year In the Life

Throughout that year, the girls will learn more than just the subject of their thesis as they share and navigate the issues that arise, including their reactions to things some have kept secret. They attend mass and adhere to the curfew, then gather after lights out to talk about everything deemed pressing.

Their conversations and reflections often lead to scenes from the past, as the reader gains insight into each of the circumstances that lead each young woman to this place.

Xenia is the first to present her thesis and to leave and she does so under cover of night, severing her connection with the girls, choosing the least conventional path, allowing an older businessman to arrange a job for her and accommodation, introducing her to a different circle of associates. Her desires are revealed in one of the early exchanges with the girls:

“Some nights a kind of yearning grips me: I can’t close my eyes and I get worn out thinking how I’m caged in this cloister of nuns, while outside life is flowing, fortune passing by – who knows? – and I can’t take advantage of it. You have to jump into life head-long, grab it by the throat. I won’t ever go back to Veroli, anyway.”

No Two Paths

If Xenia’s failure and disappearance shakes the girls up, the fate of quiet Milly, who writes letters in braille to a blind organist rocks their world even more.

As soon as Papa found out about our meetings, he made me come to Rome. But I’m not unhappy here: I can play the harmonium and write to him with that device there, which is all holes, in the braille alphabet, made just for blind people. By now I can write well, and he reads my letters by running his fingers over them, like this, see?

Silvia is a high performing literature student, a favourite of the Professor, who asks her to do research on his behalf, which he presents to great acclaim, telling her she will go far.

Silvia had on her face the expression of servile gratitude typical of those who are accustomed to submission from birth. Who were her parents, after all? Scarcely more than peasants. Someone had always taken possession of their work without even saying “Thank you, well done.” Confused by that praise, Silvia would have liked to promise : “I won’t take my eyes off the books professor, I’ll even work at night”; but at that moment Belluzzi’s wife came in, carrying a cup of tea.

Mirroring and Reflecting

Emanuela has told everyone her parents are travelling in America, disappearing every Sunday to visit her five year old daughter she has told no-one about, just like her father had written to the Mother Superior of the boarding school she attends, saying his daughter was abroad.

Though she does not study, she is drawn into the literature group, who appreciate her vigilant, intuitive faculty:

which revealed and illuminated, in those who approached her, only the aspect of the self capable of inspiring a mutual sympathy. So each saw her own image reflected, as in a mirror; and although the mirror had many faces, it projected only the one that it animated. And this game of reflections was a continuous revelation for Emanuela, too, who saw rising from the depths of herself, and appearing on the surface, constantly new and until then unknown aspects of her personality. Illuminated from the outside, exposed by the contact with others, her true physiognomy emerged gradually, and in a surprising way, from the shadows.

Women as Masters of Themselves

Augusta is enrolled in classes but doesn’t plan to sit the exams. She stays up late writing novels and sending them out. When Emanuela asks her how long she plans to stay, she replies:

Until I’ve done something. I go back to Sardinia only for a month or two, in summer. By now, one can’t go home anymore. Our parents shouldn’t send us to the city; afterward, even if we return, we’re bad daughters, bad wives. Who can forget being master of herself? And in our villages a woman who’s lived alone in the city is a fallen woman. Those who remained, who passed from the father’s authority to the husband’s, can’t forgive us for having had the key to our own room, going out and coming in when we want. And men can’t forgive us for having studied, for knowing as much as they do.

Vinca is from Spain and during her time with the girls, she learns from the newspaper that Spain is at war and that the young man she has been seeing will go and join the fight. These and subsequent events change her trajectory.

One by one, they have their experiences and they make their own decisions, no two the same, yet all of them having been through the process of living together and sharing their developing ideas, strengthening their positions and coming to some kind of resolution about how they will live their lives.

It’s another brilliant read by this fabulous author and one can just imagine how this book would have been devoured by many women in the era it was published, providing them insight and a form of company to their own thoughts, or provoking them in their solitude as they lived out those traditional paths and dreamed of something else.

Highly Recommended.

“Emanuela took her head in her hands. “I think that at a certain point you have to stop searching and accept yourself. Find the courage not to count on others anymore, to separate from childhood even at the cost of solitude;”

“It’s all a matter of courage, in life. If you have it, you do well to leave,” Augusta murmured, tapping the ashes from her cigarette.”

Further Reading

Cleveland Review of Books: An Immoral Endeavor: On Alba de Céspede’s “There’s No Turning Back” by Margarita Diaz, August 7, 2025

The Guardian: Resistance fighter, novelist – and Sartre’s favourite agony aunt: rediscovering Alba Céspedes by Lara Fiegel, Mar 2023

My reviews of Alba de Céspedes Forbidden Notebook and Her Side of The Story

Author, Alba de Céspedes

Alba de Céspedes (1911-97) was a bestselling Italian-Cuban novelist, poet and screenwriter.

The granddaughter of the first President of Cuba, de Céspedes was raised in Rome. Married at 15 and a mother by 16, she began her writing career after her divorce at the age of 20. She worked as a journalist throughout the 1930s while also taking an active part in the Italian partisan struggle, and was twice jailed for her anti-fascist activities.

After the fall of fascism, she founded the literary journal Mercurio and went on to become one of Italy’s most successful and most widely translated authors.

After the war, she accompanied her husband, a diplomat to the United States and the Soviet Union. She would later move to Paris, where she would publish her last two books in French and where she spent the rest of her life. She died in 1997.