Meytal Radzinski, the founder of #WITMonth, an initiative to encourage people to read more books by women that have been translated from another language, therefore promoting diversity, has asked readers to share their top 10 ten books by women writers in translation.

Meytal Radzinski, the founder of #WITMonth, an initiative to encourage people to read more books by women that have been translated from another language, therefore promoting diversity, has asked readers to share their top 10 ten books by women writers in translation.

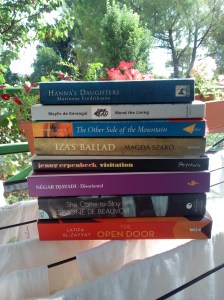

I initially shared mine in a thread on twitter, but since not everyone uses twitter, I thought I’d share my ten reads here as well before #WITMonth starts (August 1st) and if I can manage it, I may even share a picture of the pile of books from which I hope to read during August.

So here are my top 10 reads of books by women in translation, with links to my reviews, not in any particular order, although I have to say the first probably is my absolute favourite.

My Top 10 Books by Women in Translation

1. The Bridge of Beyond by Simone Schwartz-Bart (Guadeloupe) tr.Barbara Bray (French)

1. The Bridge of Beyond by Simone Schwartz-Bart (Guadeloupe) tr.Barbara Bray (French)

– the life of Telumee, the last in a line of proud Lougandor women on the French Antillean island of Guadeloupe. My Outstanding Read of 2016.

“a fluid, unveiling of a life, and a way of life, lived somewhere between a past that is not forgotten, that time of slavery lamented in the songs and felt in the bones, and a present that is a struggle and a joy to live, alongside nature, the landscape, the community and their traditions”

2. Tales From The Heart, True Stories From My Childhood by Maryse Condé (Guadeloupe)tr. Richard Philcox (French)

2. Tales From The Heart, True Stories From My Childhood by Maryse Condé (Guadeloupe)tr. Richard Philcox (French)

– essays of her early years in Guadeloupe, her education, and growing awareness of her ignorance of literature from the Caribbean & her own family history, when she moves to further her studies in Paris.

The ideal introduction to her many wondrous novels, including her masterpiece, the historical novel Segu and the novel of her grandmother’s life Victoire, My Mother’s Mother.

3. Zuleikha by Guzel Yakhina (Russia) tr. Lisa Hayden (Russian)

3. Zuleikha by Guzel Yakhina (Russia) tr. Lisa Hayden (Russian)

– an historical novel inspired by the author’s grandmother’s memories of exile in a Russian gulag (labour camp), published in English 100 years since the gulags first began in Russia.

The novel follows the story of a young woman for whom exile is a kind of emancipation, freed from the tyranny of marriage, she finds a new role and skills despite the hardship, and experiences genuine love for the first time.

4. The Baghdad Clock by Shahad Al Rawi (Iraq) tr. Luke Leafgren (Arabic)

4. The Baghdad Clock by Shahad Al Rawi (Iraq) tr. Luke Leafgren (Arabic)

– Slightly surreal, nostalgic, deeply philosophic portrayal of a neighbourhood in Baghdad, of childhood and early youth lived in the shadow of war.

We are the last teardrop aboard the ship, the last smile, the last sigh, the mast footstep on its ageing pavement. We are the last people to line their eyes with its dust. We are the ones who will tell its full story. We will tell it to neighbours’ children born in foreign countries, to their grandchildren not yet born – we, the witnesses of everything that happened.

5. Disoriental by Negar Djavadi (Iran) tr. Tina Kover (French)

5. Disoriental by Negar Djavadi (Iran) tr. Tina Kover (French)

– the story of a family forced to flee Iran, a family history, a modern young woman now living in France, sits in a fertility clinic but something about her situation isn’t as it should be, she reflects on the past, while waiting to control the outcome of her present, a clash of the old and the new.

“That’s the tragedy of exile. Things, as well as people, still exist, but you have to pretend to think of them as dead.”

6. So Long A Letter by Mariama Bâ (Senegal) tr. Modupé Bodé Thomas (French)

6. So Long A Letter by Mariama Bâ (Senegal) tr. Modupé Bodé Thomas (French)

– an epistolary novella, a letter from a widow to her best friend, reflecting on the emotional fallout of her husband’s death, unable to detach from memories of better times, a lament.

I am not indifferent to the irreversible currents of the women’s liberation that are lashing the world. This commotion that is shaking up every aspect of our lives reveals and illustrates our abilities.

My heart rejoices every time a woman emerges from the shadows. I know that the field of our gains is unstable, the retention of conquests difficult: social constraints are ever-present, and male egoism resists.

Instruments for some, baits for others, respected or despised, often muzzled, all women have almost the same fate, which religions or unjust legislation have sealed.

7. The Complete Claudine by Colette (France) tr. Antonia White (French)

7. The Complete Claudine by Colette (France) tr. Antonia White (French)

– Claudine at school, in Paris, in Marriage and with her friend Annie, the unfettered, exuberant joys of teenage freedom vs the the slap in the face of an approaching adult, urban world.

“a novel that anticipates by ninety years, the contemporary fashion for wry, first-person narratives by single, thirty something career women. Its heroine examines her addictions to men with amused detachment, and flirts, alternately, with abstinence and temptation. Is there love without complete submission and loss of identity? Is freedom really worth the loneliness that pays for it? These are Colette’s abiding questions.”

8. Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi (Egypt) tr. Sherif Hetata (Arabic)

8. Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi (Egypt) tr. Sherif Hetata (Arabic)

– an Egyptian woman is imprisoned for killing a man, soon to be executed. Nawal El Saadawi gains permission to interview before her death. A spell-binding tale of lifelong oppression & desire to be free of it, told with compassionate sensitivity.

The idea of ‘prison’ had always exercised a special attraction for me. I often wondered what prison life was like, especially for women. Perhaps this was because I lived in a country where many prominent intellectuals around me had spent various periods of time in prison for ‘political offences’. My husband had been imprisoned for thirteen years as a ‘political detainee’.

9. Human Acts by Han Kang (South Korea) tr. Deborah Smith (Korean)

9. Human Acts by Han Kang (South Korea) tr. Deborah Smith (Korean)

– the Gwangju massacre in South Korea in 1980 witnessed from multiple perspectives, an attempt at understanding humanity.

At night, though, when all the grown-ups were all sitting in the kitchen and I knew I’d be safe…I crept into the main room in search of that book. I scanned every spine until finally I got to the top shelf; I still remember the moment when my gaze fell upon the mutilated face of a young woman, her features slashed through with a bayonet. Soundlessly, and without fuss, some tender thing deep inside me broke. Something that, until then, I hadn’t even realised was there.

10. The Wall by Marlen Haushofer (Austria) tr. Shaun Whiteside (German)

10. The Wall by Marlen Haushofer (Austria) tr. Shaun Whiteside (German)

– living behind an invisible wall, alone, with a few animals, a stream of consciousness narrative of one woman’s courageous survival, using the feminine instinct .

The Wall is a muted critique of consumerism and a delicate poem in praise of nature, a challenge to violence and patriarchy, an encomium to peace and life-giving femininity, a meditation on time, an observation on the differences and similarities between animals and humans, and a timeless minor masterpiece.

If you have a top 5 or 10 to share, or even just one favourite, share it on twitter or instagram using the hashtag below:

The reason they are highlighted in August is an attempt to raise awareness of the very narrow choice we give ourselves by only reading books in English, or from one’s own country and to highlight the fact that even when we do read outside our first language, the majority of books published, promoted and reviewed are written by men.

The reason they are highlighted in August is an attempt to raise awareness of the very narrow choice we give ourselves by only reading books in English, or from one’s own country and to highlight the fact that even when we do read outside our first language, the majority of books published, promoted and reviewed are written by men.

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir Hanna has one daughter, Johanna, a name that carries its own story and past, before she is even born, one of the reasons she is closer to her father in her early years. Johanna would also have one daughter Anna, it is she who begins to narrate this story, she visits her mother in hospital, desperate to get answers to questions she has left it too late to ask.

Hanna has one daughter, Johanna, a name that carries its own story and past, before she is even born, one of the reasons she is closer to her father in her early years. Johanna would also have one daughter Anna, it is she who begins to narrate this story, she visits her mother in hospital, desperate to get answers to questions she has left it too late to ask. The first half of the book is dedicated to Hanna and her life and this is where the novel is at its best, immersed in the struggle of Hanna’s early years, its tragic turning point and the situation she is forced to accept as a result. Circumstances that will become buried deep, that nevertheless leave their impression on how she is in the world and impact those daughters indirectly.

The first half of the book is dedicated to Hanna and her life and this is where the novel is at its best, immersed in the struggle of Hanna’s early years, its tragic turning point and the situation she is forced to accept as a result. Circumstances that will become buried deep, that nevertheless leave their impression on how she is in the world and impact those daughters indirectly.

The Other Side of the Mountain by Erendiz Atasü is one of those books I came across in a blog post I read in 2017, a post entitled

The Other Side of the Mountain by Erendiz Atasü is one of those books I came across in a blog post I read in 2017, a post entitled

I’m glad The Open Door was brought back into publication, it was a landmark work in woman’s writing in Arabic when it was first published in 1960, an important commentary on the challenges women and girls in so many societies face, a consequence of patriarchy; an effect that is being busted wide open today, forcing transparency, offering support, healing and with hope, gradual change in many countries today. It seems timely to revisit this, or to read it for the first time, as will likely be the case for many.

I’m glad The Open Door was brought back into publication, it was a landmark work in woman’s writing in Arabic when it was first published in 1960, an important commentary on the challenges women and girls in so many societies face, a consequence of patriarchy; an effect that is being busted wide open today, forcing transparency, offering support, healing and with hope, gradual change in many countries today. It seems timely to revisit this, or to read it for the first time, as will likely be the case for many.

About her novel, she had this to say:

About her novel, she had this to say:

The narrating of family stories, taking us back as far as her great-grandfather Montazemolmolk with his harem of 52 wives, serves to provide context and an explanation for why certain family members might have behaved or lived in the way they did, helping us understand their motives and actions.

The narrating of family stories, taking us back as far as her great-grandfather Montazemolmolk with his harem of 52 wives, serves to provide context and an explanation for why certain family members might have behaved or lived in the way they did, helping us understand their motives and actions.

I’ve attempted to read Visitation about four times and never succeeded in getting past the first few chapters, but this year I persevered as I felt I hadn’t given it a fair chance.

I’ve attempted to read Visitation about four times and never succeeded in getting past the first few chapters, but this year I persevered as I felt I hadn’t given it a fair chance.

Although I’ve read reviews and seen this book appear often over the last year, and knew I really wanted to read it, I couldn’t remember what is was about or why.

Although I’ve read reviews and seen this book appear often over the last year, and knew I really wanted to read it, I couldn’t remember what is was about or why. The British translation (by Jessica Moore) is entitled Mend the Living, broader in scope, it references the many who lie with compromised organs, who dwell in a twilight zone of half-lived lives, waiting to see if their match will come up, knowing when it does, it will likely be a sudden opportunity, to receive a healthy heart, liver, or kidney from a donor, taken violently from life.

The British translation (by Jessica Moore) is entitled Mend the Living, broader in scope, it references the many who lie with compromised organs, who dwell in a twilight zone of half-lived lives, waiting to see if their match will come up, knowing when it does, it will likely be a sudden opportunity, to receive a healthy heart, liver, or kidney from a donor, taken violently from life. The translator Jessica Moore refers to her task in translating the authors work, as ‘grappling with Maylis’s labyrinthe phrases’, which can feel like what it must be like to be an amateur surfer facing the wave, trying and trying again, to find the one that fits, the wave and the rider, the words and the translator. She gives up trying to turn what the author meant into suitable phrases and leaves interpretation to the future, potential reader, us.

The translator Jessica Moore refers to her task in translating the authors work, as ‘grappling with Maylis’s labyrinthe phrases’, which can feel like what it must be like to be an amateur surfer facing the wave, trying and trying again, to find the one that fits, the wave and the rider, the words and the translator. She gives up trying to turn what the author meant into suitable phrases and leaves interpretation to the future, potential reader, us. As The Story of the Cannibal Woman opens, we learn Rosélie is a 50-year-old recent widow, living alone, without family connections and few friends in Cape Town, South Africa, after the brutal murder of her white British husband, a retired university professor, who nipped out after midnight one evening, allegedly to buy cigarettes and never returned home.

As The Story of the Cannibal Woman opens, we learn Rosélie is a 50-year-old recent widow, living alone, without family connections and few friends in Cape Town, South Africa, after the brutal murder of her white British husband, a retired university professor, who nipped out after midnight one evening, allegedly to buy cigarettes and never returned home. At the same time Rosalie is going through her crisis, there is a well publicised case in the newspapers of a woman named Fiela, who allegedly murdered her husband. In court she refuses to speak, the public begin to turn against her, some calling her a witch, others a cannibal. The police officer on Stephen’s case wonders aloud whether she might open up to Rosalie, as many of her patients do. Rosalie has imaginary conversations with Fiela, the one personality to whom she feels able to ask questions (albeit in her dreams), that she can not utter to anyone else:

At the same time Rosalie is going through her crisis, there is a well publicised case in the newspapers of a woman named Fiela, who allegedly murdered her husband. In court she refuses to speak, the public begin to turn against her, some calling her a witch, others a cannibal. The police officer on Stephen’s case wonders aloud whether she might open up to Rosalie, as many of her patients do. Rosalie has imaginary conversations with Fiela, the one personality to whom she feels able to ask questions (albeit in her dreams), that she can not utter to anyone else:

The Complete Claudine by Colette tr. Antonia White (French) – Colette began her writing career with Claudine at School, which catapulted the young author into instant, sensational success. Among the most autobiographical of Colette’s works, these four novels are dominated by the child-woman Claudine, whose strength, humour, and zest for living make her a symbol for the life force.

The Complete Claudine by Colette tr. Antonia White (French) – Colette began her writing career with Claudine at School, which catapulted the young author into instant, sensational success. Among the most autobiographical of Colette’s works, these four novels are dominated by the child-woman Claudine, whose strength, humour, and zest for living make her a symbol for the life force.