Women in Translation

Tidal Waters is my first August read for #WIT month. Reading Women in Translation.

What an original, good-hearted, open, vulnerable read. I’m not sure whether what I read was fictional or not, because much of what is described in the ‘letters to a close friend’ coincides with elements in the author bio inside the front cover of the book and the main character is Vel.

The Epistolary Novel

An epistolary narrative, it is about the return to a place and finding new purpose, along with the motivation to pursue it and taking others with you – told through a correspondence that bears witness and though we don’t see the replies, we can tell that they encourage and support both the idea(s) and the woman pursuing it.

I don’t know if I mentioned this specifically, perhaps not in a letter, though maybe when we met up before I left to come and live here here for good, but part of what pushed me to make this radical life change was the need to feel that my existence had meaning, that I was spending each day doing something I cared about and could feel proud of at the end of my life. And that’s just what I found in being Seño Velia, the woman who has meetings with people about books, who tries to motivate children to love reading and books as much as she does, and who supports the teachers.

Finding Purpose and Motivation, In Community

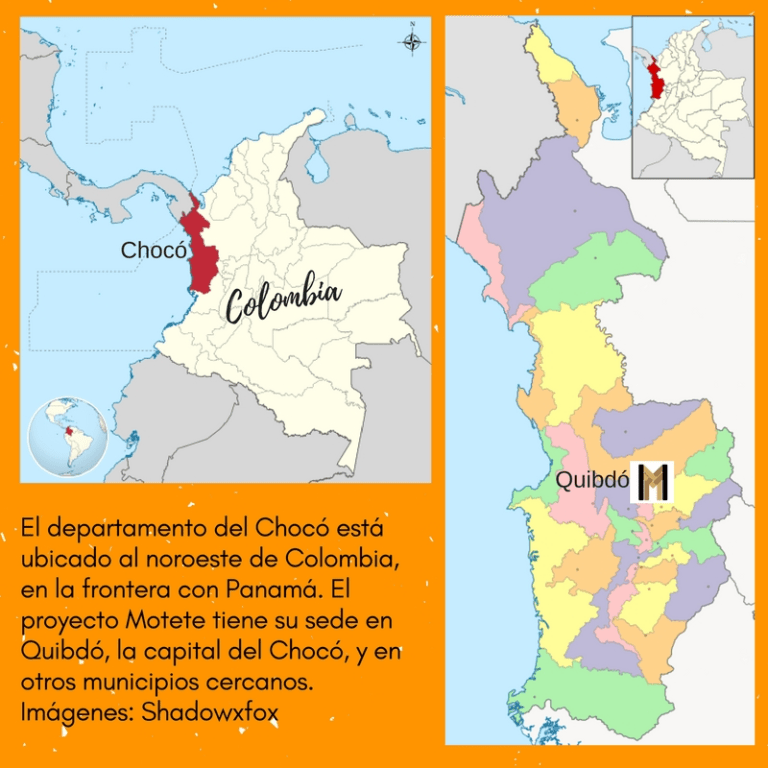

The letters span 3 years from May 2015 and they track a significant change in Vel’s life as she decides to return to Choco (to the Afro-Colombian community she was raised in) to start a new venture to bring reading, literacy and a love of books to it. The correspondence exhibits the growth and expansion of her writing, the letter becomes a safe harbour and she tests it by taking her writing to another level, stretching into a more personal yet contained arena.

Tomorrow I start a diploma in reading promotion, and with it my project, Motete. We’ve chosen three areas of Quibdo where I’ll start running the workshops.

She is taking a risk starting a new venture, but believes in it and is surrounded by extended family and connections, which facilitate her ability to reach out even further into the community and invite everyone in, to be part of or benefit from her shared love of reading.

And so this project is coming together. This basket, this Motete, is filling up. The slogan for my project is ‘Contenidos que tejen’ – contents that weave – and every day I like it more. Every day I realise that these contents are weaving fulfillment and happiness within me…

The thing is, motetes have been used to carry food for the body: plaintains, bushmeat, fish. Our is to fill them with food for the soul: art, culture, books. And just as motetes are woven by hand, I thought these new contents would also form a fabric: the fabric of society, of community, the fabric of souls.

Letter Writing

Her unnamed friend that she writes to is someone she hasn’t known long, he occupies a space between the familiar and the unfamiliar that she claims as a freedom to express herself, to be vulnerable and open, someone who has mentored and shown her how to get funding. The range of things she will write to him of, span a wide spectrum.

We never see the replies but the continuation of her own correspondence displays her life, her dealing with health problems, the double bind of her wounding and love, of being raised by doting grandparents, while having complicated relationships with a teenage mother unable to mother her and an emotionally absent father. Her later sadness and depression, helped through therapy, tears and conversations, to ways of coping and healing. Her optimism for her venture, and the community connections she creates keep her going.

I grew a lot. I learned. But most of all I tried to weave a new way of relating to my father that hurt as little as possible.

The Sea, The Sea

One of the themes is the sea, the absence of sea, the way the river meets the sea and her relationship to it. She yearns for it when it has been absent for some time, just as she yearns for the letter writer and the relief that comes in the act of writing to him.

She describes herself in her current role as being like the sea at that place where it meets the river.

I’m like the Pacific Ocean, pressing at the river with its tides to make it flow the other way, or lapping at the land when its waters rise, when it feels like gaining inches of new ground. You need strong motivation to stick to this way of life, which isn’t exactly a fight against the world, but rather the certainty of forging your own path.

An Homage to Correspondence

I loved this slender book, it’s project and generosity, its intimate sharing and platform for expanding and learning and having the courage to venture into new areas. It made me think of an exquisite title I’d forgotten about, Leslie Marmon Silko’s slim book of correspondence The Delicacy and Strength of Lace: Letters Between Leslie Marmon Silko and James Wright.

That correspondence was written when Silko was 31 years old and Wright 51. They had planned to meet in the Spring of 1980, mentioned in letters of Oct/Nov of the previous year, not knowing he would be gone before then.

They discuss her novel, his poetry, language, his travels, her adventures with animals, their speaking engagements, their mutual challenges and experiences as university professors, and soon began to share more personal feelings, as she acknowledged the tough time she was having and he shared his own experience, expressing empathy.

Velia Vidal dedicates her book:

To my recipient,

simply for being there.

and when I read about her own projects in society, her love of the sea and shared readings and efforts to help move children and young adults out of poverty, it is all the more inspirational to read these letters, understanding the difference a letter can make, to see someone take a risk and pursue something that will help others from her community, while fulfilling her own dreams and aspirations.

Highly Recommended.

Velia Vidal, Author

Velia Vidal (Bahía Solano, Colombia, 1982) is a writer who loves the sea and shared readings. In 2021 she was a fellow at Villa Josepha Ahrenshoop, in Germany.

For her book Tidal Waters she won the Afro-Colombian Authors Publication Grant awarded by Colombia’s Ministry of Culture. She is the co-author of Oír somos río (2019) and its bilingual German-Spanish edition.

She is the founder and director of the Motete Educational and Cultural Corporation and the Reading and Writing Festival (FLECHO) in Chocó, one of the most isolated, complex and neglected regions in Colombia with the highest afro-descendant population density in the country.

Vidal graduated in Afro-Latin American Studies and has a Masters in Reading Education and Children’s Literature. She is also a journalist and specialist in social management and communication. In 2022 she was included in the list of 100 most influential and inspiring women in the world by the BBC.

She writes children’s literature, fiction and non-fiction, and poetry. Her work has been translated into German, English and Portuguese.