It’s tough to have to choose one, and all the books below have been excellent reads, but the one standout for me was Prayers for the Stolen, because I haven’t stopped thinking about it all year, it’s always top of mind when anyone asks me about a good book I’ve read recently, just as I still recommend Caroline Smailes The Drowning of Arthur Braxton from 2013 and Eowyn Ivey’s The Snow Child from 2012, all outstanding reads.

The Stats

This year I read 57 books, basically one book a week, 79% of my reads were fiction, 16% non-fiction and 5% poetry. I managed to read books by authors from 18 different countries and this year 40% of what I read was translated from another language. 54% of the books I read were printed books and 46% I read on a kindle. 63% were written by a female author.

Outstanding Read of the Year 2014

Prayers For The Stolen by Jennifer Clement

This book had a huge impact on me at the time of reading, a fictional account of a girl named Ladydi growing up in a part of Mexico where it is dangerous to be a girl, so the mother’s disguise them as boys, from the moment of their birth.

This book had a huge impact on me at the time of reading, a fictional account of a girl named Ladydi growing up in a part of Mexico where it is dangerous to be a girl, so the mother’s disguise them as boys, from the moment of their birth.

An insightful read, about a tragic issue, told with empathy and humour and helping to raise awareness of the plight of so many women and girls unable to speak out for themselves. A must read.

And in no particular order, My Top Reads for 2014!

Top Fiction

1.Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin (translated from Russian by James E. Falen)

The epic book length poem Eugene Onegin was my surprise read of the year and pure delight. I avoided reading it for years and years thinking it would be inaccessible. It was hilarious and a riveting read.

The epic book length poem Eugene Onegin was my surprise read of the year and pure delight. I avoided reading it for years and years thinking it would be inaccessible. It was hilarious and a riveting read.

I read it two chapters at a time in a read along and was thoroughly entertained by that cad Eugene Onegin and bemused by that reader of far too many romantic novels Tatiana, and broken-hearted at the fate of the poet. Absolutely brilliant and I would quite like to read another translation after some of the comparisons other readers made as we read, what turns out to be not quite the same version. More Pushkin definitely.

2. Nada by Carmen Laforet (translated from Spanish by Edith Grossman)

Nada was being passed around friends all exclaiming its wonder, a book written by the author when she was 23 years old and based on her own similar experience as a young woman moving to Barcelona to study. It takes place in the shadowy aftermath of a traumatic civil war, its effect hanging over her family. Andrea, now an orphan, arrives to stay with relatives, however her stay is not as she’d imagined it, the family are full of eccentricities and Andrea finds more refuge in the gloomy streets and with her new friends than in the oppressive atmosphere of the apartment among her strange relatives. A feverish, coming of age classic.

Nada was being passed around friends all exclaiming its wonder, a book written by the author when she was 23 years old and based on her own similar experience as a young woman moving to Barcelona to study. It takes place in the shadowy aftermath of a traumatic civil war, its effect hanging over her family. Andrea, now an orphan, arrives to stay with relatives, however her stay is not as she’d imagined it, the family are full of eccentricities and Andrea finds more refuge in the gloomy streets and with her new friends than in the oppressive atmosphere of the apartment among her strange relatives. A feverish, coming of age classic.

3. We That Are Left by Juliet Greenwood

A title I was waiting for, having loved Eden’s Garden and this promised to be just as good, set in World War One and featuring a cast of women characters who are changed by the war in ways that will continue long after.

A title I was waiting for, having loved Eden’s Garden and this promised to be just as good, set in World War One and featuring a cast of women characters who are changed by the war in ways that will continue long after.

From Cornwall to Wales to France, we follow Elin as her husband leaves for the war and she must assume responsibility for the family estate and is propelled into a dangerous mission to rescue her friend in the thick of fighting. It concerns the changes thrust upon women during the war and their refusal to go back to the more submissive role that was expected of them before the war. They prove they are just as capable of handling a crisis and if necessary will manage on their own. Brilliant, thrilling and unputdownable.

4.The True Deceiver by Tove Jansson (translated from Swedish by Thomas Teal)

The True Deceiver is the first novel I have read by Tove Jansson, having read three collections of her short stories (The Summer Book, A Winter Book and Art in Nature) all of which I enjoyed, so this was an interesting departure to stay with the same characters throughout and it is quite a thrilling read, clearly inspired in part by her own experience, facing up to the artist struggle.

The True Deceiver is the first novel I have read by Tove Jansson, having read three collections of her short stories (The Summer Book, A Winter Book and Art in Nature) all of which I enjoyed, so this was an interesting departure to stay with the same characters throughout and it is quite a thrilling read, clearly inspired in part by her own experience, facing up to the artist struggle.

It is the perfect winter read, set in the snow bound winter months, while they await the thaw. Anna is an aging artist who lives alone and is content for it to be that way, her contact with the outside world through the many letters from her fans. But someone in the village has other plans and slowly makes herself indispensable to the older woman, preying on her vulnerabilities. And the true deceiver? That is the question that reading the novel reveals.

4. My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante (translated from Italian by Ann Goldstein)

If you haven’t yet succumbed to #FerranteFever keep an eye out for this book and the two that follow it, The Story of a New Name and Those Who Leave & Those Who Stay. They narrate a friendship between Elena and Lila, set in an impoverished neighbourhood of Naples, one tries to escape her place in society via a university education and a marriage that will elevate her status while the other uses her intelligence in a relentless, fearless and often ruthless quest to survive. The books are compelling and may be semi-autobiographical, however the author remains an enigma, using a pseudonym and not ready to own up to his/her identity – believing that if a book has any merit, it will find its audience.

If you haven’t yet succumbed to #FerranteFever keep an eye out for this book and the two that follow it, The Story of a New Name and Those Who Leave & Those Who Stay. They narrate a friendship between Elena and Lila, set in an impoverished neighbourhood of Naples, one tries to escape her place in society via a university education and a marriage that will elevate her status while the other uses her intelligence in a relentless, fearless and often ruthless quest to survive. The books are compelling and may be semi-autobiographical, however the author remains an enigma, using a pseudonym and not ready to own up to his/her identity – believing that if a book has any merit, it will find its audience.

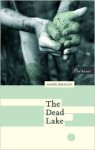

5. The Dead Lake by Hamid Ismialov (translated from Russian by Andrew Bromfield)

This is why I wait until the end of the year before creating my list, because who knows what special book gems we might discover before the final curtain call. The Dead Lake is part of the Peirene Press coming-of-age series published in 2014 and tells the story of Yerzhan, a boy growing up at a remote railway siding in Kazakhstan, an area where atomic weapon testing is carried out.

There are only two communities where he lives and he adores the neighbour’s daughter and it is to impress her that he walks into that lake at 12-years-old and stops growing. It is a stunning and unforgettable novella and an insightful glimpse into a nomadic culture, that we are privileged to be able to read thanks to the passionate endeavours of our friends at Peirene Press.

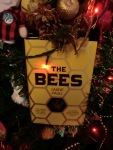

6. The Bees by Laline Paull

The Bees is an extraordinary feat of the imagination, narrated from the point of view of Flora 717 a sanitation worker bee. It is about life in an orchard hive and the threats both internal and external to the hive. Totally convincing, the Hive is like a cult and each bee knows its place, its role and responds by instinct and receives energy from the Hive Mind, the Queen and the collective conscience of the Hive. Flora is different and as we discover why, we begin to fear for her life. A stunning, original work, I was enthralled but the story and love that the author was inspired by a Bronze Age Minoan palace in translating a real beehive into a fictional landscape.

Top Non-Fiction

1. Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader by Anne Fadiman

1. Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader by Anne Fadiman

This was the very first book of the year I read and a special read for booklovers. It contains 18 bookish essays from the bibliophile Anne Fadiman, written over a period of four years, in which she talks about how she became so book obsessed and shares many often hilarious anecdotes. It was also recommended and gifted to me by the talented blogger and world-wide reader VishyThe Knight.

2. Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez

2. Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez

First published in 1986 and winner of the National Book Award for non-fiction in the US, Artic Dreams is a compilation of poetic nature essays written by a compassionate, scientific, nature loving mind, as he observes those creatures whose natural habitat is the arctic, whether they are polar bears, seals or Arctic people. Some of my best recommendations, as was the case with this book, come from Valorie at Books Can Save a Life.

3. Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain

3. Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain

I planned to read this right from the beginning of 2014 when it was republished as an anniversary edition to commemorate the beginning of World War one. Vera Brittain was an intellect and despite it being seen as a waster of time by many ion the provinces where she came from she set of for Oxford to compete with the boys, whom most of her friends were.

One by one, her friends, her brother, her fiance went off to fight and not able to concentrate on something that seemed meaningless in the face of war, she volunteered as a nurse. Testament of Youth is taken from her journals and is an insightful, at times heartbreaking insight into a lost youth, and an attempt to understand humanity and to prevent us from repeating the same mistakes. A brilliant book, about to be released as a feature film.

4. H is for Hawk by Wendy Macdonald

4. H is for Hawk by Wendy Macdonald

There haven’t been so many non fiction titles that called out to me this year, but this one did immediately and I pushed it to the top of the pile to read and was riveted by Helen Macdonald’s grief stricken, obsessive encounter with Mebel, he Goshawk she raises, spurning human company and comfort in the aftermath of her father’s death. Great to see it then win the Samuel Johnson prize.

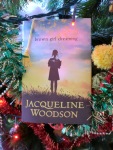

5. Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

5. Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

What a delightful memoir in free verse from a well-known children’s writer, writing of her childhood spent between South Carolina and Brooklyn, NY tales of family members, a new brother, her passion for words, being Jehovah Witness and making a great friend. Reminds me of the equally talented Margarita Engle and her collection of novels in verse.

Voila!

So what was your outstanding read(s) for 2014?

Nina Sankovitch has a more romantic view of letters and letter writing and the word joy in the title is a clue. She doesn’t speak of the suffering of not receiving letters, she speaks of the joys of connection.

Nina Sankovitch has a more romantic view of letters and letter writing and the word joy in the title is a clue. She doesn’t speak of the suffering of not receiving letters, she speaks of the joys of connection.

Still To Read

Still To Read