I am reading The True Deceiver as part of my #TOVE100 Reading Challenge.

This is the first of Tove Jansson’s novels I have read that flows like a single story, her A Winter Book and The Summer Book read like vignettes, not driven so much by plot, more focused on the characters that inhabited their pages, their environment and various encounters that carried them through the season.

The seasons are ever present in all her work and in The True Deceiver, we meet the characters snow-bound in winter, waiting for the thaw of spring. This passage of time will thaw the surroundings and to a certain degree the characters as they undergo a transformation due to the events that follow.

“It was an ordinary dark winter morning, and snow was still falling. No window in the village showed a light.”

The True Deceiver is the story of an aging woman artist Anna Aemelin who lives alone on the outskirts of small village, snow bound as the opening pages reveal its stillness and propensity for chatter within. Anna keeps to herself and is content that way, her post and necessary supplies are delivered, there is minimal disruption to her way of life and the inspiration that feeds her artistic leanings, which awaken with the Spring and her venturing into the woodland beyond her home.

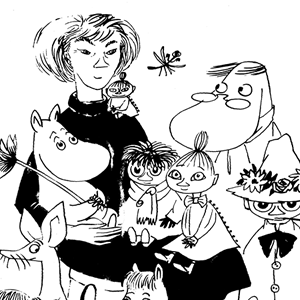

She often receives correspondence from fans, her art depicts realistic portrayals of the forest floor, disturbed only by the presence of her not so life-like animated rabbits, for which she is world-renowned, especially among the younger generation.

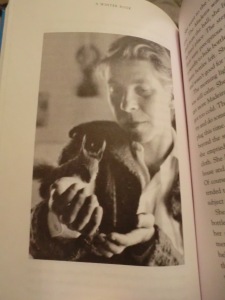

As Boel Westin notes in Tove Jansson Life, Art, Words: The Authorised Biography, Jansson often writes herself into her fiction:

“Sometimes unconcealed, freely, openly, sometimes hidden behind various names and disguises…traces of Tove Jansson run hither and thither in all her texts and pictures, and the patterns they form are constantly new” Boel Westin

One of the villagers, Katri Krill, known to all as being good with numbers, one who can sniff out the slightest hint of corruption or exploitation, dreams of financial security for herself and her brother Mats. Despite her trustworthiness, her sudden interest in the aging artist sets tongues wagging in the village, as she takes over more and more of Anna’s business affairs, bringing her out of an oblivious state of denial regarding her situation, an interference that is both appreciated and resented equally.

“Now don’t take this the wrong way, Miss Kling, but I find your way of never saying what a person expects you to say, I find it somehow appealing. In you, there’s no, if you’ll pardon my saying so, no trace of what people call politeness… And politeness can sometimes be almost a kind of deceit, can it not? Do you know what I mean?”

When Katri takes over the letter writing activity to Anna’s child fans, the artist is appalled to learn how business like and impersonal her responses are, it might take less time, but it is not her style at all and she lets her know exactly how it should be:

“And what about this one? Anna went on. “Where’s the chitchat? He’s tried to draw a rabbit – obviously no talent at all – so here you could write something like ‘I’ve hung your picture above my desk’… This one’s learning to skate, and her cat’s name is Topsy. You can fill nearly a whole page with the skating and the cat if you write big enough. You’re not using the material.”

It is as though Tove Jansson is arguing with herself, Katri is like her alter ego and Anna resists embracing what she knows should be done, it undermines her integrity as an artist, she resents all the questions relating to the ugly business of merchandising that has grown like a malignant tumour out of her artwork; people take these things on, come up with ideas that have nothing to do with her work or her characters and their inclinations and want to do things with them, that in her imagination she knows they would never do. Katri tries to get her to detach from them, trying to convince her that she will never see these manifestations of her work, she should see them purely as a source of income, but Anna will not compromise, the artist’s integrity is not for sale.

Who is the true deceiver? Perhaps everyone has something of the deceiver in them, the truth can be brutal, kindness can be deceptive, secondary agendas can lie behind them both. The True Deceiver is Tove Jansson at her best, struggling and yet persevering to put into story form, the battle of those two states of mind, objectivity and aesthetic sensibility, constantly at war with each other, unlikely companions just as Anna and Katri, the rabbits and the dog.

Brilliantly evocative of the artistic struggle, it is a story that invites discussion and keeps the reader thinking long after that last page is turned. And wondering what those rabbits might have looked like, Moomins perhaps?

Highly Recommended.

Still To Read

Still To Read