Sylvia Boorstein’s Happiness is an Inside Job is an easy-reading distillation of the key components of Buddhist thought and practise shared through a lifetime of experiences.

The Dalai Lama

“We’ll start as the Buddha did in his declaration of what is fundamentally true about life, with the premise that challenges in life are inevitable and that suffering, the mind in contentious mode with its experience, is the instinctive response of the untrained mind.

These premises are the first two of the famous Four Noble Truths regarded as the summation of the Buddha’s teaching.

The third truth is the definite promise that a peaceful mind, one not in contention with anything, is a possibility for human beings.

The fourth truth is the Buddha’s training program for developing that kind of mind.”

That training is basically about how to cultivate what we call ‘equanimity’, that ability to be in a situation and at the same time, be outside the situation observing it happening and our response to it, learning to use that ability to shape how we respond, from one of the great Buddhist intellects living today.

Boorstein’s book (reviewed below) talks us through the various components of developing and nurturing that wisdom, using examples from her and her friend’s lives. Before reviewing that text, and to give it context from my own personal reading, I share below a few enlightened books I’ve read over the years that penetrate this wisdom with clarity, insight and offer helpful and realistic suggestions for their practical application.

The 14th Dalai Lama

Some of my favourite books are those written by the 14th Dalai Lama, spiritual leader of Tibet, holder of the Nobel Peace prize, philosopher, intellectual, a genuinely altruistic man of great wisdom and compassion.

Many of them I pass on to others as they are too full of penetrating insights and ideas for changing our thinking in a positive way, to let waste away on a dusty shelf. I thought I’d share three that come immediately to mind, because they each had a significant impact when I read them:

Transforming the Mind: Teachings on generating compassion – this one is based on an edited series of lectures and is full of excellent practical advice and mind training on how to modify our perceptions to create a more compassionate view. This is his most important work in my opinion, it has some philosophical sections that are a little harder to grasp, but it is so worth persevering to get to the real wisdom within.

Transforming the Mind: Teachings on generating compassion – this one is based on an edited series of lectures and is full of excellent practical advice and mind training on how to modify our perceptions to create a more compassionate view. This is his most important work in my opinion, it has some philosophical sections that are a little harder to grasp, but it is so worth persevering to get to the real wisdom within.

I remember when I read it, how well it resonated and how much I learned and was able to apply, it was quite a revelation the first time I read it. Such a gift.

Ancient Wisdom, Modern World Ethics for the New Millennium was published just before the millennium, a beautiful, small hard-cover book that reached out to all beings, not just those interested in Buddhism, addressing the spiritual void in a non-religious way and bringing attention to ethics and to finding new ways of living that avoid destroying nature and the environment, protecting our shared inheritance.

Ancient Wisdom, Modern World Ethics for the New Millennium was published just before the millennium, a beautiful, small hard-cover book that reached out to all beings, not just those interested in Buddhism, addressing the spiritual void in a non-religious way and bringing attention to ethics and to finding new ways of living that avoid destroying nature and the environment, protecting our shared inheritance.

I remember that this was the first book of his, that I felt completely comfortable handing on to almost anyone, it surpassed belief and spoke to us all, no matter what our faith or spiritual inclination, this is an important and accessible message for humanity.

How to See Yourself As You Really Are – this book is a lighter, practical guide to understand the nature of self, examining how many of the things we currently believe to be solid are an illusion and that by appreciating this, we can learn how to minimise suffering.

How to See Yourself As You Really Are – this book is a lighter, practical guide to understand the nature of self, examining how many of the things we currently believe to be solid are an illusion and that by appreciating this, we can learn how to minimise suffering.

His older books tend to be more philosophical and can at times be a challenge to understand the way of thinking, all of which is encouraged in Buddhist thought – that we should question in order to understand – however this book is more of a modern interpretation, written not for the scholar or practitioner but for anyone with an interest in self-improvement and understanding the mind.

By the time I read this one, I recognised much of the message, it wasn’t so new to me, I was already living it, but we always need reminding and encouraging, as the path is littered with obstacles!

Review: Happiness is an Inside Job

This book was a delightful Christmas gift I was promised I would enjoy, described by Publishers Weekly as:

This book was a delightful Christmas gift I was promised I would enjoy, described by Publishers Weekly as:

‘a small, polished gem of a book’

I had not heard of Sylvia Boorstein, one of the co-founding teachers at Spirit Rock Meditation Centre in California. She has written a number of books on Buddhist thinking, meditation, mindfulness and kindness.

In Happiness is an Inside Job, she shows how mindfulness, concentration, and effort–three elements of the Buddhist path to wisdom–can lead us away from anger, anxiety, and confusion, and into calmness, clarity, and the joy of living in the present.

Split into sections on equanimity, wise effort (and speech), mindfulness, and concentration it uses anecdotes and examples in everyday life to illustrate how to put this philosophy of compassion into practice.

It sounds like common sense and indeed it is, however the mind often loses track and imagines, worries, obsesses and does everything but choose the path of common sense and we often need to be reminded of the most simple observations to declutter it.

She reminds us that much that happens in our lives is external to us and beyond our control, but that our response to it is within our ability to manage and there is much we can do to help ourselves by learning how to respond in a way that will calm and nurture us, that we can choose to respond in a way that veers more toward the path of happiness.

‘Speech that compliments is, by definition, free from derision, which clouds the mind with enemies and makes it tense. Kind speech makes the mind feel safe and also glad.’

It’s a book to read a chapter at a time, not all at once, an alternative to the demands of fiction, more nourishing than television, food for the soul. Recommended as an introduction to Buddhist thought and the benefits of practising compassion.

“My practise is remembering that although whatever is happening, including my emotional response to it, is the lawful consequence of myriad causes that are beyond my control, the relationship I hold toward it all is within my control. I can choose on behalf of happiness.”

Jane Bowles (born in New York City, Feb 1917) wrote one novel, a play and six short stories. The novel Two Serious Ladies, though panned at the time, (critic Edith Walton writing in the Times Book Review didn’t understand it, calling it ‘senseless and silly’), became regarded as a modernist, cult classic, helped when Tennessee Williams named it his favourite book.

Jane Bowles (born in New York City, Feb 1917) wrote one novel, a play and six short stories. The novel Two Serious Ladies, though panned at the time, (critic Edith Walton writing in the Times Book Review didn’t understand it, calling it ‘senseless and silly’), became regarded as a modernist, cult classic, helped when Tennessee Williams named it his favourite book.

The novel unfolds and weaves like threads in a tapestry, as characters share their understanding of Billy, their memories of his charm and inclinations and what they knew about the short-lived romance with the Irish girl Eva.

The novel unfolds and weaves like threads in a tapestry, as characters share their understanding of Billy, their memories of his charm and inclinations and what they knew about the short-lived romance with the Irish girl Eva.

February is a novel constructed around a real and tragic historical event that occurred in Newfoundland, Canada just over thirty years ago, a tragedy that remains deeply felt in the area today. All Newfoundlanders of a certain age, remember where they were on the night the Ocean Ranger sank, a technological wonder that was supposed to be unsinkable, one that if safety procedures had been followed, indeed, may not have done so.

February is a novel constructed around a real and tragic historical event that occurred in Newfoundland, Canada just over thirty years ago, a tragedy that remains deeply felt in the area today. All Newfoundlanders of a certain age, remember where they were on the night the Ocean Ranger sank, a technological wonder that was supposed to be unsinkable, one that if safety procedures had been followed, indeed, may not have done so.

From whispering muse to the gift of stones, this was the second book I read in 2016, one of Jim Crace’s earlier philosophical works, telling the tale of a village of stone workers, who live a simple life working stone into weapons, which are then traded with passers-by for food and other essentials, which they are not able to provide for themselves, in the arid landscape within which they reside. It is a livelihood they think little about, it is all they know.

From whispering muse to the gift of stones, this was the second book I read in 2016, one of Jim Crace’s earlier philosophical works, telling the tale of a village of stone workers, who live a simple life working stone into weapons, which are then traded with passers-by for food and other essentials, which they are not able to provide for themselves, in the arid landscape within which they reside. It is a livelihood they think little about, it is all they know.

Skloot made Henrietta the subject of her research for 10 years in the creation of this thorough, respectful account of the life of Henrietta Lacks and her journey to uncover the events of the time within the context of what was the norm in her day.

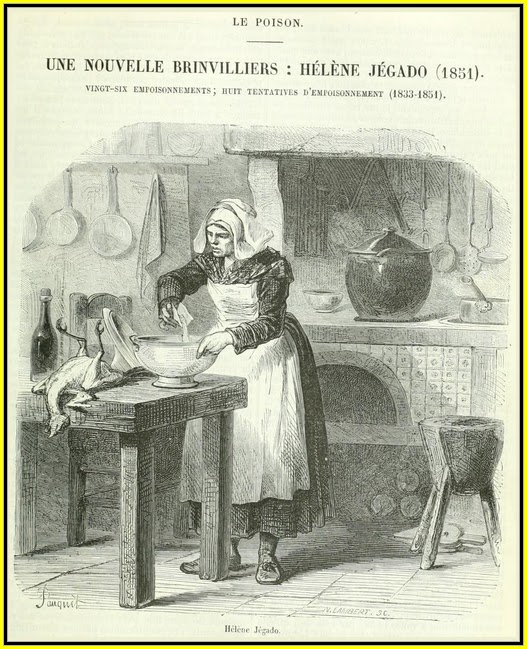

Skloot made Henrietta the subject of her research for 10 years in the creation of this thorough, respectful account of the life of Henrietta Lacks and her journey to uncover the events of the time within the context of what was the norm in her day. A real-life character tour de force from French author Jean Teulé featuring a famous female serial killer from the nineteenth century.

A real-life character tour de force from French author Jean Teulé featuring a famous female serial killer from the nineteenth century. ‘The Ankou wears a cloak and a broad hat,’ said Anne Jégado, sitting down again. ‘He always carries a scythe with a sharpened blade. He’s often depicted as a skeleton whose head swivels constantly at the top of his spine like a sunflower on its stem so that with one glance he can take in the whole region his mission covers.’

‘The Ankou wears a cloak and a broad hat,’ said Anne Jégado, sitting down again. ‘He always carries a scythe with a sharpened blade. He’s often depicted as a skeleton whose head swivels constantly at the top of his spine like a sunflower on its stem so that with one glance he can take in the whole region his mission covers.’

Her novel Heremakhonon(1976), which I’ve not yet read, is a semi-autobiographical story of a sophisticated Caribbean woman, teaching in Paris, who travels to West Africa in search of her roots and an aspect of her identity she has no connection with.

Her novel Heremakhonon(1976), which I’ve not yet read, is a semi-autobiographical story of a sophisticated Caribbean woman, teaching in Paris, who travels to West Africa in search of her roots and an aspect of her identity she has no connection with. In 1797, the kingdom of Segu is thriving, its noblemen are prospering, its warriors are prominent and powerful, at their peak.

In 1797, the kingdom of Segu is thriving, its noblemen are prospering, its warriors are prominent and powerful, at their peak.

Elizabeth Gilbert, author of the best seller Eat Pray Love and more recently in 2013, the historical, botanical novel

Elizabeth Gilbert, author of the best seller Eat Pray Love and more recently in 2013, the historical, botanical novel

Ford went on: “I say this to you only because writing is clearly bringing you no pleasure. It is only bringing you pain. Our time on earth is short and should be enjoyed. You should leave this dream behind and go find something else to do with your life. Travel, take up new hobbies, spend time with your family and friends, relax. But don’t write anymore, because it’s obviously killing you.”

Ford went on: “I say this to you only because writing is clearly bringing you no pleasure. It is only bringing you pain. Our time on earth is short and should be enjoyed. You should leave this dream behind and go find something else to do with your life. Travel, take up new hobbies, spend time with your family and friends, relax. But don’t write anymore, because it’s obviously killing you.” Gilbert gave her a brief outline and asked Patchett what her novel was about and she repeated almost word for word the same idea – fitting into her theory that the idea had visited her and because she had put it aside for a couple of years, it left and had been passed on to Patchett to become

Gilbert gave her a brief outline and asked Patchett what her novel was about and she repeated almost word for word the same idea – fitting into her theory that the idea had visited her and because she had put it aside for a couple of years, it left and had been passed on to Patchett to become

hough in contrast to that epic tome that won the Man Booker Prize in 2013, Rose Tremain’s novel features only one man seduced by the gold or and gives us an insight into two women, Harriet his wife and Lilian his mothers, their hopes, achievements and personal struggles in trying to make a life in this untamed country.

hough in contrast to that epic tome that won the Man Booker Prize in 2013, Rose Tremain’s novel features only one man seduced by the gold or and gives us an insight into two women, Harriet his wife and Lilian his mothers, their hopes, achievements and personal struggles in trying to make a life in this untamed country. They know it will be a tough existence and they will need to learn from mistakes, as all pioneers do, but they find the challenges of this harsh Canterbury landscape almost soul destroying and Joseph is quickly lured away by the glitter and promise of gold dust he finds in his river and soon sets off to join the other men, also seduced by their lust for “the colour”, in new goldfields over the Southern Alps, leaving the two women to fend for themselves.

They know it will be a tough existence and they will need to learn from mistakes, as all pioneers do, but they find the challenges of this harsh Canterbury landscape almost soul destroying and Joseph is quickly lured away by the glitter and promise of gold dust he finds in his river and soon sets off to join the other men, also seduced by their lust for “the colour”, in new goldfields over the Southern Alps, leaving the two women to fend for themselves.