Cold Enough for Snow is a 96 page literary fiction novella set in Japan, that can be read in an afternoon.

Mother Daughter Relationships

It is an intricate, observant story told by a daughter who has arranged to take her mother on holiday to Japan. She recounts their days and interactions and tries to anticipate what her mother might like, knowing that the intersection of their common interests is negligible.

It is an intricate, observant story told by a daughter who has arranged to take her mother on holiday to Japan. She recounts their days and interactions and tries to anticipate what her mother might like, knowing that the intersection of their common interests is negligible.

Mother and daughter have been raised in different countries and cultures, additionally the mother was not raised in the same country as her parents, so both have grown up migrants, knowing little about what came before, except that it has influenced the way they would have been raised.

Do We Ever Really Know Our Mother?

There is a void, a vacuity, a kind of absence of understanding that is very present, in terms of the way the daughter tries to feel her way towards guessing what her mother might like, what to propose to her. The mother doesn’t have set ideas or desires regarding what they might do, she is like a stranger, a visitor to the holiday, not exhibiting the same kind of intentionality that the daughter possesses.

Earlier in the year, I had asked her to come with me on a trip to Japan. We did not live in the same city anymore, and had never been away together as adults, but I was beginning to feel it was important, for reasons I could not yet name. At first, she had been reluctant, but I had pushed, and eventually she had agreed, not in so many words, but by protesting slightly less, or hesitating over the phone when I asked her, and by those acts alone, I knew that she was finally signalling that she would come. I had chosen Japan because I had been there before, and although my mother had not, I thought she might be more at ease exploring another part of Asia. And perhaps I felt this would put us on equal footing in some way, to both be made strangers.

Photo by Tomu0e on Pexels.com

It was autumn and though pretty, there had been adverse weather warnings.

The daughter describes the minutiae of their every movement, of taking trains, changing platforms, the places they visit, the flora and fauna, occasionally flashing back to memories to when she travelled with her husband Laurie; wishing that the same excitement of discovery she’d had with him might be present with her mother.

She also recalls how difficult her younger sister was, growing up. Now a mother herself, she is dealing with difficult behaviours that have passed through to her own child, little understanding why she had been so troubled.

Ask Me No Questions, I Tell You No Lies

She tries to engage her mother in conversation, they talk; the daughter asks questions, the mother answers.

I thought about how vaguely familiar this scene was to me, especially with the smells of the restaurant around me, but strangely so, because it was not my childhood, but my mother’s childhood that I was thinking of, and from another country at that. And yet there was something about the subtropical feel, the smell of the steam and the tea and the rain…

It was strange at once to be so familiar and yet so separated. I wondered how I could feel so at home in a place that was not mine.

Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

The daughter has had a particular education that influences the way she observes things, she wants to share that with her mother, she tries, mostly her mother smiles when she shares these perspectives, but it is impossible to tell if she agrees.

Whenever I’d asked her what she’d like to visit in Japan, she’d often said she would be happy with anything. The only question she’d asked once was whether, in winter, it was cold enough for snow, which she had never seen.

Existential Beliefs and Nothingness

One day the daughter desires to visit a church, reportedly a beautiful building designed by a famous architect, in a suburb near Osaka. Though she knew her mother did not believe in that religion, visiting that place was supposed to be a profound experience, it provoked and exchange between the two.

I asked my mother what she believed about the soul and she thought for a moment. Then, looking not at me but at the hard, white light before us, she said that she believed that we were all essentially nothing, just series of sensations and desires, none of it lasting. When she was growing up, she said that she had never thought of herself in isolation, but rather as inextricably linked to others. Nowadays, she said, people were hungry to know everything, thinking that they could understand it all, as if enlightenment were just around the corner. But, she said, in fact there was no control, and understanding would not lessen any pain. The best we could do in this life was to pass through it, like smoke through the branches, suffering, until we either reached a state of nothingness, or else suffered elsewhere.

The novella presents these two women and the things they do, snippets of their one sided conversations, their attempt to bond, to find a connection. They are transparent, one thing they have in common is the inability to pretend, there is no falseness, they are a product of those environments they’ve grown up trying to fit into, familiar yet unfamiliar, known, yet unknown, compelled by life’s circumstance to remain an enigma to each other.

It was an interesting read, that palpable desire to connect, the deep chasm between them, born of something outside their control, yet the human need to try and persevere, to find a way through anyway.

Further Reading:

Interview Bomb magazine: Chasing the Echoes of Belonging: Jessica Au Interviewed by Madelaine Lucas

Review, the guardian: a graceful novella about how we pay attention

Jessica Au, Author

Jessica Au is a writer, editor and bookseller based in Melbourne, Australia.

Cold Enough for Snow won the inaugural Novel Prize in 2022, run by Giramondo, New Directions and Fitzcarraldo Editions, and is set to be published in eighteen countries. Au won both the 2023 Victorian Premier’s Prize for Literature and Victorian Premier’s Prize for Fiction for Cold Enough for Snow.

“Migration is probably the one through line of my family. My grandfather migrated from China to Malaysia, my mother migrated from Malaysia to Australia. So, that’s three generations of migration. When I was younger, I would take my mother’s language and refer to Malaysia as “home”. Where I was living, where I was born, was never “home”. Even after living in Australia for so many years, that idea of home being elsewhere is constant and present. I don’t have a sense of belonging anywhere.” Jessica Au, interview, Bomb Magazine

Marzhan Mon Amour is a memoir-ish novel, collective history and a character study of a group of people living in and around a multi-storied communist-era plattenbau prefab apartment building in the working class quarter of Marzahn, East Berlin, told through the eyes and ears of a woman facing her middle years.

Marzhan Mon Amour is a memoir-ish novel, collective history and a character study of a group of people living in and around a multi-storied communist-era plattenbau prefab apartment building in the working class quarter of Marzahn, East Berlin, told through the eyes and ears of a woman facing her middle years. Brazilian author, Ana Paula Maia’s Of Cattle and Men, was an interesting and confronting story that in parts was hyper realistic in a visceral way, and fable-like in other ways. It is the fourth book I’ve read this year from the

Brazilian author, Ana Paula Maia’s Of Cattle and Men, was an interesting and confronting story that in parts was hyper realistic in a visceral way, and fable-like in other ways. It is the fourth book I’ve read this year from the

36 year old Koko raises her 11 year old daughter Kayako alone, she works part time teaching piano, though the way she is obliged to teach it pains her. Since she bought her apartment (thanks to a partial inheritance) she has also become independent of her family, something her sister Shoko constantly criticizes her for.

36 year old Koko raises her 11 year old daughter Kayako alone, she works part time teaching piano, though the way she is obliged to teach it pains her. Since she bought her apartment (thanks to a partial inheritance) she has also become independent of her family, something her sister Shoko constantly criticizes her for.

Yuko Tsushima (1947-2016) was a prolific writer, known for her stories that centre on women striving for survival and dignity outside the confines of patriarchal expectations. Groundbreaking in content and style, Tsushima authored more than 35 novels, as well as numerous essays and short stories.

Yuko Tsushima (1947-2016) was a prolific writer, known for her stories that centre on women striving for survival and dignity outside the confines of patriarchal expectations. Groundbreaking in content and style, Tsushima authored more than 35 novels, as well as numerous essays and short stories. This is the novel I have been waiting for Jan Carson to write, for here is a writer who in her ordinary life as an arts facilitator has brought together people from opposite sides in their way of thinking, encouraging them to sit down and write little stories, enabling them to imagine from within the shoes of an(other) – teaching the practice of empathy.

This is the novel I have been waiting for Jan Carson to write, for here is a writer who in her ordinary life as an arts facilitator has brought together people from opposite sides in their way of thinking, encouraging them to sit down and write little stories, enabling them to imagine from within the shoes of an(other) – teaching the practice of empathy.

At only 76 pages, it is a brief recollection that begins in quiet, dramatic form as she recalls the day her father, at the age of 67, unexpectedly, quite suddenly dies.

At only 76 pages, it is a brief recollection that begins in quiet, dramatic form as she recalls the day her father, at the age of 67, unexpectedly, quite suddenly dies. Ernaux’s father was fortunate to remain in education until the age of 12, when he was hauled out to take up the role of milking cows. He didn’t mind working as a farmhand. Weekend mass, dancing at the village fetes, seeing his friends there. His horizons broadened through the army and after this experience he left farming for the factory and eventually they would buy a cafe/grocery store, a different lifestyle.

Ernaux’s father was fortunate to remain in education until the age of 12, when he was hauled out to take up the role of milking cows. He didn’t mind working as a farmhand. Weekend mass, dancing at the village fetes, seeing his friends there. His horizons broadened through the army and after this experience he left farming for the factory and eventually they would buy a cafe/grocery store, a different lifestyle. Born in 1940,

Born in 1940,  I admire the way Claire Keegan creates atmosphere and a sense of place, I could well imagine the small Irish town they lived, the cold, the workplace, the river – although I had to keep reminding myself it was the 1980’s and that there was electricity. Bill’s deliveries of wood and coal and the way the women made it feel like a much earlier era, though I don’t doubt it was freezing then as few could afford to heat their homes by other means.

I admire the way Claire Keegan creates atmosphere and a sense of place, I could well imagine the small Irish town they lived, the cold, the workplace, the river – although I had to keep reminding myself it was the 1980’s and that there was electricity. Bill’s deliveries of wood and coal and the way the women made it feel like a much earlier era, though I don’t doubt it was freezing then as few could afford to heat their homes by other means.

It made me recall another character, Albert, from the film

It made me recall another character, Albert, from the film  From the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 until 1996, at least 10,000 girls and women were imprisoned, forced to carry out unpaid labour and subjected to severe psychological and physical maltreatment in Ireland’s Magdalene Institutions. These were carceral, punitive institutions that ran commercial and for-profit businesses primarily laundries and needlework.

From the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 until 1996, at least 10,000 girls and women were imprisoned, forced to carry out unpaid labour and subjected to severe psychological and physical maltreatment in Ireland’s Magdalene Institutions. These were carceral, punitive institutions that ran commercial and for-profit businesses primarily laundries and needlework. This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness.

This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness. It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s

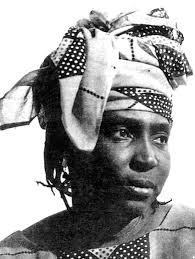

It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s  Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.

Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents. Such Small Hands is an incredible and unique novella, quite unlike anything I have read, it’s written almost from another dimension. The author somehow enters into a childlike perspective and witnesses the aftermath of a car accident in which the child Marina’s parents don’t survive.

Such Small Hands is an incredible and unique novella, quite unlike anything I have read, it’s written almost from another dimension. The author somehow enters into a childlike perspective and witnesses the aftermath of a car accident in which the child Marina’s parents don’t survive. Inspired by a disturbing event, this enters the realm of post trauma in an innocent and bizarre way, taking the reader back to a kind of twilight zone of an insecure childhood, where the nightmare becomes real and the line between reality and dreams is blurred.

Inspired by a disturbing event, this enters the realm of post trauma in an innocent and bizarre way, taking the reader back to a kind of twilight zone of an insecure childhood, where the nightmare becomes real and the line between reality and dreams is blurred. A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche.

A mysterious novella that begins in a quiet humble way as we meet the young widow Yasuko whose husband, the only son of Meiko Togano, we learn died tragically in an avalanche. It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese.

It is worth knowing a little about the plot of The Tale of Genji and the ‘Masks of Noh’ from the dramatic plays, as we realise there are likely to be references and connections to what is unfolding here. And not surprising given Fumiko Enchi translated this 1,000+ page novel into modern Japanese. Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors.

Fumiko Enchi was a Tokyo born novelist and playright, the daughter of a distinguished philologist and linguist. Poorly as a child, she was home-schooled in English, French and Chinese literature by private tutors.