Dear Husband,

I lost our children today.

What an opening line. Tahmima Anam’s A Golden Age plunges you right into the twin events that form the basis of Rehana’s character as a parent, fiercely protective and determined to have them near her.

Dear Husband,

Our children are no longer our children.

The death of her husband and her fight to keep her children, when her dead husband’s brother and his childless wife claim they could take better care of them.

The first chapter begins with that day in 1959 when the court gives custody to her brother and sister-in-law, who live in Lahore, (West Pakistan) over 1000 miles and an expensive flight away from Dhaka (East Pakistan).

The novel then jumps forward and is set in 1971, in Dhaka, the year of its war of independence, when East separated from West Pakistan and became Bangladesh (when you look at the area on a map, they are geographically separate, with no common border, India lies between them).

In 1971, Rehana’s children, Maya and Sohail are university students and back living with their mother after she discovered a way of becoming financially independent without having to remarry. Despite her efforts to protect them, she is unable to stop them becoming involved in the events of the revolution, her son joining a guerrilla group of freedom fighters and her daughter leaving for Calcutta to write press releases and work in nearby refugee camps.

He’ll never make a good husband, she heard Mrs Chowdhury say. Too much politics.

The comment had stung because it was probably true. Lately the children had little time for anything but the struggle. It had started when Sohail entered the university. Ever since ’48, the Pakistani authorities had ruled the eastern wing of the country like a colony. First they tried to force everyone to speak Urdu instead of Bengali. They took the jute money from Bengal and spent it on factories in Karachi and Islamabad. One general after another made promises they had no intention of keeping. The Dhaka university students had been involved in the protests from the very beginning, so it was no surprise Sohail had got caught up, Maya too. Even Rehana could see the logic: what sense did it make to have a country in two halves, posed on either side of India like a pair of horns?

Rather than lose her children again, Rehana supports them and their cause, finding herself on the opposite side of a conflict to her disapproving family who live in West Pakistan.

As she recited the pickle recipe to herself, Rehana wondered what her sisters would make of her at this very moment. Guerillas at Shona. Sewing kathas on the rooftop. Her daughter at rifle practice. The thought of their shocked faces made her want to laugh.She imagined the letter she would write. Dear sisters, she would say. Our countries are at war; yours and mine. We are on different sides now. I am making pickles for the war effort. You see how much I belong here and not to you.

Anam follows the lives of one family and their close neighbours, illustrating how the historical events of that year affected people and changed them. It is loosely based on a similar story told to the author by her grandmother who had been a young widow for ten years already, when the war arrived.

When I first sat down to write A Golden Age, I imagined a war novel on an epic scale. I imagined battle scenes, political rallies, and the grand sweep of history. But after having interviewed more than a hundred survivors of the Bangladesh War for Independence, I realised it was the very small details that always stayed in my mind- the guerilla fighters who exchanged shirts before they went into battle, the women who sewed their best silk saris into blankets for the refugees. I realised I wanted to write a novel about how ordinary people are transformed by war, and once I discovered this, I turned to the story of my maternal grandmother, Mushela Islam, and how she became a revolutionary.

It’s a fabulous and compelling novel of a family disrupted by war, thrown into the dangers of standing up for what they believe is right, influenced by love, betrayed by jealousies and of a young generation’s desire to be part of the establishment of independence for the country they love.

It is also the first novel in the Bangladesh trilogy, the story continues in the books I will be reading next The Good Muslim and the recently published The Bones of Grace.

Tahmima Anam was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh, but grew up in Paris, Bangkok and New York. She earned a Ph.D. in Social Anthropology from Harvard University and a Master’s degree in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway in London. A Golden Age won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book and was the first of a planned trilogy she hoped would teach people about her native country and the vicious power of war.

In 2013 she was included in the Granta list of 20 best young writers and her follow-up novel The Good Muslim was nominated for the 2011 Man Asian Literary Prize.

February is a novel constructed around a real and tragic historical event that occurred in Newfoundland, Canada just over thirty years ago, a tragedy that remains deeply felt in the area today. All Newfoundlanders of a certain age, remember where they were on the night the Ocean Ranger sank, a technological wonder that was supposed to be unsinkable, one that if safety procedures had been followed, indeed, may not have done so.

February is a novel constructed around a real and tragic historical event that occurred in Newfoundland, Canada just over thirty years ago, a tragedy that remains deeply felt in the area today. All Newfoundlanders of a certain age, remember where they were on the night the Ocean Ranger sank, a technological wonder that was supposed to be unsinkable, one that if safety procedures had been followed, indeed, may not have done so.

From whispering muse to the gift of stones, this was the second book I read in 2016, one of Jim Crace’s earlier philosophical works, telling the tale of a village of stone workers, who live a simple life working stone into weapons, which are then traded with passers-by for food and other essentials, which they are not able to provide for themselves, in the arid landscape within which they reside. It is a livelihood they think little about, it is all they know.

From whispering muse to the gift of stones, this was the second book I read in 2016, one of Jim Crace’s earlier philosophical works, telling the tale of a village of stone workers, who live a simple life working stone into weapons, which are then traded with passers-by for food and other essentials, which they are not able to provide for themselves, in the arid landscape within which they reside. It is a livelihood they think little about, it is all they know.

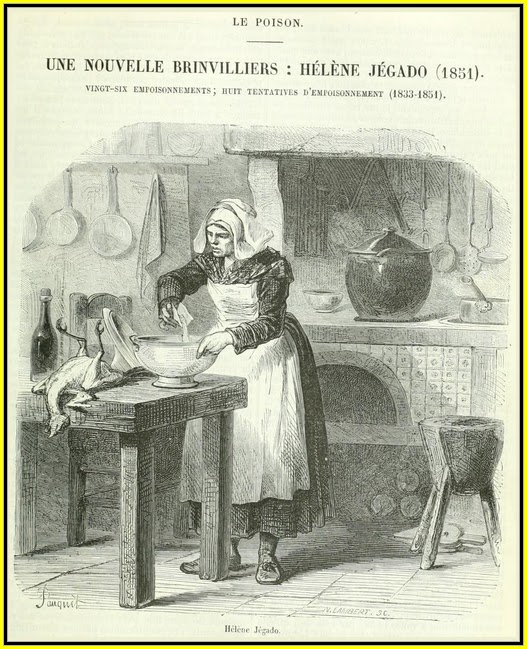

A real-life character tour de force from French author Jean Teulé featuring a famous female serial killer from the nineteenth century.

A real-life character tour de force from French author Jean Teulé featuring a famous female serial killer from the nineteenth century. ‘The Ankou wears a cloak and a broad hat,’ said Anne Jégado, sitting down again. ‘He always carries a scythe with a sharpened blade. He’s often depicted as a skeleton whose head swivels constantly at the top of his spine like a sunflower on its stem so that with one glance he can take in the whole region his mission covers.’

‘The Ankou wears a cloak and a broad hat,’ said Anne Jégado, sitting down again. ‘He always carries a scythe with a sharpened blade. He’s often depicted as a skeleton whose head swivels constantly at the top of his spine like a sunflower on its stem so that with one glance he can take in the whole region his mission covers.’

Her novel Heremakhonon(1976), which I’ve not yet read, is a semi-autobiographical story of a sophisticated Caribbean woman, teaching in Paris, who travels to West Africa in search of her roots and an aspect of her identity she has no connection with.

Her novel Heremakhonon(1976), which I’ve not yet read, is a semi-autobiographical story of a sophisticated Caribbean woman, teaching in Paris, who travels to West Africa in search of her roots and an aspect of her identity she has no connection with. In 1797, the kingdom of Segu is thriving, its noblemen are prospering, its warriors are prominent and powerful, at their peak.

In 1797, the kingdom of Segu is thriving, its noblemen are prospering, its warriors are prominent and powerful, at their peak.

hough in contrast to that epic tome that won the Man Booker Prize in 2013, Rose Tremain’s novel features only one man seduced by the gold or and gives us an insight into two women, Harriet his wife and Lilian his mothers, their hopes, achievements and personal struggles in trying to make a life in this untamed country.

hough in contrast to that epic tome that won the Man Booker Prize in 2013, Rose Tremain’s novel features only one man seduced by the gold or and gives us an insight into two women, Harriet his wife and Lilian his mothers, their hopes, achievements and personal struggles in trying to make a life in this untamed country. They know it will be a tough existence and they will need to learn from mistakes, as all pioneers do, but they find the challenges of this harsh Canterbury landscape almost soul destroying and Joseph is quickly lured away by the glitter and promise of gold dust he finds in his river and soon sets off to join the other men, also seduced by their lust for “the colour”, in new goldfields over the Southern Alps, leaving the two women to fend for themselves.

They know it will be a tough existence and they will need to learn from mistakes, as all pioneers do, but they find the challenges of this harsh Canterbury landscape almost soul destroying and Joseph is quickly lured away by the glitter and promise of gold dust he finds in his river and soon sets off to join the other men, also seduced by their lust for “the colour”, in new goldfields over the Southern Alps, leaving the two women to fend for themselves.

Ijeoma was living with her parents in their yellow painted home surrounded by rose and hibiscus bushes, immersed in the aroma of orange, guava, cashew and mango trees, in the village of Ojoto, where vendors lined the street and life had a slow, amiable pace when war broke out between Biafra and Nigeria.

Ijeoma was living with her parents in their yellow painted home surrounded by rose and hibiscus bushes, immersed in the aroma of orange, guava, cashew and mango trees, in the village of Ojoto, where vendors lined the street and life had a slow, amiable pace when war broke out between Biafra and Nigeria.

Hugo knows she has a night life that his parents aren’t aware of and begins to follow her to try to discover where she goes and what she does. He is equally afraid, given his own history of instability and wonders if it may be himself who is responsible and though he cannot prove it, it is to hear his confession and description of what he found at the scene of the murder of one of his friends, that opens the first pages of the novel. It is Hugo who narrates this story of how the savage girl came into their lives and all the events that followed.

Hugo knows she has a night life that his parents aren’t aware of and begins to follow her to try to discover where she goes and what she does. He is equally afraid, given his own history of instability and wonders if it may be himself who is responsible and though he cannot prove it, it is to hear his confession and description of what he found at the scene of the murder of one of his friends, that opens the first pages of the novel. It is Hugo who narrates this story of how the savage girl came into their lives and all the events that followed.