Astonishing, a work of art, an interwoven tapestry of stories that weave across the generations to create something so beautiful, so heartfelt, the thing that connects them is so strong, even when it isn’t known by its characters, somehow Yaa Gyasi conveys that to the reader, so that by the end when something quite magical happens, there is a feeling of grieving for all that has passed and of relief that something new has been found.

Astonishing, a work of art, an interwoven tapestry of stories that weave across the generations to create something so beautiful, so heartfelt, the thing that connects them is so strong, even when it isn’t known by its characters, somehow Yaa Gyasi conveys that to the reader, so that by the end when something quite magical happens, there is a feeling of grieving for all that has passed and of relief that something new has been found.

I love, love, loved this novel and I am in awe of its structure and storytelling, the authenticity of the stories, the three-dimensional characters, the inheritance and reinvention of trauma, and the rounding of all those stories into the healing return. I never saw that ending coming and the build up of sadness from the stories of the last few characters made the last story all the more moving, I couldn’t stop the tears rolling down my face.

How to give it justice in a review, it is so much more than story, we are so much more than our own personal experience and the place(s) we have lived.

Novels That Ask Questions

Just as Han Kang, the South Korean author of the novel Human Acts wrote in consideration of two fundamental questions about humanity, Yaa Gyasi tells us in an article for the New York Times (referenced below) that she too began to write with a vague but important question that she put at the top of her blank screen: What does it mean to be black in America?

She further explains her inspiration in an article for the Observer (also below)

I began Homegoing in 2009 after a trip to Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle [where slaves were incarcerated]. The tour guide told us that British soldiers who lived and worked in the castle often married local women – something I didn’t know. I wanted to juxtapose two women – a soldier’s wife with a slave. I thought the novel would be traditionally structured, set in the present, with flashbacks to the 18th century. But the longer I worked, the more interested I became in being able to watch time as it moved, watch slavery and colonialism and their effects – I wanted to see the through-line.

The Legacy of Generations

Homegoing begins with the image of a partial family tree, with two strands and the novel will follow just one family member down each strand, the first two characters who begin these family lines are the daughters of Maame, Effia and Esi.

Effia, whom the villagers said was a baby born of the fire, believed she would marry the village chief, but would be married to a British slave trader and live upstairs in the Cape Coast Castle.

‘The night Effia Otcher was born into the musky heat of Fanteland, a fire raged through the woods just outside her father’s compound. It moved quickly, tearing a path for days. It lived off the air; it slept in caves and hid in trees; it burned, up and through, unconcerned with what wreckage it left behind, until it reached an Asante village. There, it disappeared, becoming one with the night.’

Effia’s father, Cobbe would lose his crop of yams that night, a precious crop known to sustain families far and wide and with it, through his mind would flit a premonition that would reverberate through subsequent generations:

He knew then that the memory of the fire that burned, then fled, would haunt him, his children, and his children’s children for as long as the line continued.’

Cape Coast Castle (a slave trading castle), Ghana

Esi, whose father was a Big Man, in expressing her empathy for their house girl, would precipitate events that lead her to be captured and chained in the dungeons beneath that same castle, awaiting the slave trading ships that would transport them to their slave masters in America.

‘They took them out into the light. The scent of ocean water hit her nose. The taste of salt clung to her throat. The soldiers marched them down to an open door that led to sand and water, and they all began to walk out on to it.’

Symbolism

In these first two chapters of Effia and Esi, the recurring twin symbols of fire and water are introduced, something that each generation subconsciously carries with them and passes on, they will reappear through fears, dreams, experiences, a kind of deep primal scar they don’t even know requires healing, its origins so far back, so removed from anything that can be easily articulated.

Fire (yang) is like the curse of the slave trade, raging through the lives of each generation, even when they appear to have escaped it, as with Kojo’s story, a baby passed to the arms of a woman who helped slaves escape, whose parents are captured, but he will live freely, only to have one member of the family cruelly snatched, perpetuating the cycle yet again, orphaning another child, who must start over and scrape together a life from nothing.

‘They didn’t now about Jo’s fear of people in uniform, didn’t know what it was like to lie silent and barely breathing under the floorboards of a Quaker house, listening to the sound of a catcher’s boot heel stomp above you. Jo had worked so hard so his children wouldn’t have to inherit his fear, but now he wished they had just the tiniest morsel of it.’

Water (yin) to me is the endless expanse, the rootlessness, floating on the surface, feet never able to get a grip, efforts floundering. This symbol is carried throughout Essi’s family line, a cast of characters whose wheels are turning, who work hard, but suffer one setback after another.

The novel is structured around one chapter for each character, alternately between the twin sides of the family, the narrative perspective changing to focus on the new generation, through whom we learn something of what happened to the character in the previous generation, who’ve we left two chapters ago.

Importantly, because Yaa Gyasi decides not to write in the present with flashbacks, but writes from the perspective of each character in their present, the novel never falters, it doesn’t suffer from the idling effect of flashbacks, it keeps up the pace by putting the reader at the centre of the drama in every chapter. We must live all of it.

The irony of the structure is that we read an entire family history and see how the events of the past affect the future, how patterns repeat, how fears are carried forward, how strong feelings are connected to roots and origins, we see it, while they experience the loss, the frustration, the inability to comprehend that it is not just the actions of one life that affect that life’s outcome.

This book is like a legacy, a long legacy that revolves between the sadness of loss and the human struggle to move forward, to survive, to do better, to improve. And also a legacy of the feeling of not belonging that is carried within those who have been uprooted, who no longer belong to one place or another, who if they are lucky might find someone to whom they can ignite or perhaps even extinguish that yearning ‘to belong’.

‘We can’t go back to something we ain’t never been to in the first place. It ain’t ours anymore. This is.’ She swept her hand in front of her, as though she were trying to catch all of Harlem in it, all of New York, all of America.’

And in writing this novel, Yaa Gyasi perhaps achieves something of what her final character Marcus is unable to articulate to Marjorie as to why his research feels futile, spurning his grandmother’s suggestion that he perhaps had the gift of visions, trying to find answers in a more tangible way, through research and study.

“What is the point Marcus?”

She stopped walking. For all they knew, they were standing on top of what used to be a coal mine for all the black convicts who had been conscripted to work there. It was one thing to research something, another thing entirely to have lived it. To have felt it. How could he explain to Marjorie that what he wanted to capture with his project was the feeling of time, of having been a part of something that stretched so far back, was so impossibly large, that it was easy to forget that she, and he, and everyone else, existed in it – not apart from it, but inside it.

Yes, she achieves it through literature, through fiction. And this is literature at its most powerful and best.

This novel is going to win awards in 2017, undoubtedly.

*****

Yaa Gyasi

Yaa Gyasi was born in Ghana in 1989 and raised in the US, moving around in early childhood but living in Huntsville, Alabama from the age of 10. She is the daughter of a francophone African literature professor and a nurse and completed her MFA at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, University of Iowa. She wrote this, her debut novel at the age of 26.

Further Reading

New York Times, Sunday Review – Opinion, June 18, 2016 – I’m Ghanaian-American. Am I Black?

Review, The Observer, January 8, 2017 – Yaa Gyasi: ‘Slavery is on people’s minds. It affects us still’

This stylised memoir, set in the working-class north of England, is the book Jeanette Winterson wasn’t ready to write back in 1985 when at 25 years of age, she wrote the novel Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, a book that plunged the reader into her universe, one that provided the author the liberty of narrating freely, without the confines of the story having to have been exactly as she had lived it – it was fiction, an imagined story, and she named the main character Jeanette, a provocative gesture for sure.

This stylised memoir, set in the working-class north of England, is the book Jeanette Winterson wasn’t ready to write back in 1985 when at 25 years of age, she wrote the novel Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, a book that plunged the reader into her universe, one that provided the author the liberty of narrating freely, without the confines of the story having to have been exactly as she had lived it – it was fiction, an imagined story, and she named the main character Jeanette, a provocative gesture for sure.

How to Be Brave isn’t just a book you read, it’s a story that you feel like you are living while reading, right down to sharing the symptoms and emotions of some of its characters. I didn’t just read this book, I experienced it, developed symptoms and was grateful for medicine and the time to rest and recuperate from it. But fear not, it’s totally worth the ride.

How to Be Brave isn’t just a book you read, it’s a story that you feel like you are living while reading, right down to sharing the symptoms and emotions of some of its characters. I didn’t just read this book, I experienced it, developed symptoms and was grateful for medicine and the time to rest and recuperate from it. But fear not, it’s totally worth the ride. Louise Beech has created a page-turning, moving story that on Day 2 of reading, which was also Day 2 post-op for my daughter who also has Type 1 diabetes (diagnosed at 9 year-old), but who is recovering currently from spinal surgery to correct a scoliosis related curvature, I began to develop symptoms of headache, dehydration and my body ached all over. I wasn’t sure if it was sympathetic pain for my daughter or for Colin, I couldn’t read, just as Colin and the men couldn’t always find the energy to keep a lookout and gave into sleep, and so did I, after a quick trip to the pharmacy for medicine and water, so dehydrated! Miraculously, the next day I was completely fine.

Louise Beech has created a page-turning, moving story that on Day 2 of reading, which was also Day 2 post-op for my daughter who also has Type 1 diabetes (diagnosed at 9 year-old), but who is recovering currently from spinal surgery to correct a scoliosis related curvature, I began to develop symptoms of headache, dehydration and my body ached all over. I wasn’t sure if it was sympathetic pain for my daughter or for Colin, I couldn’t read, just as Colin and the men couldn’t always find the energy to keep a lookout and gave into sleep, and so did I, after a quick trip to the pharmacy for medicine and water, so dehydrated! Miraculously, the next day I was completely fine.

The novel is predominantly a second person narrative addressed to Elijah, long after she has lost him, narrating the events of their meeting, her pursuit of the dinosaur fossils straight after meeting him, her return to Dhaka and then her escape from her family to Chittagong, to work alongside a female film-maker interviewing workers on the ship graveyards, beaches where enormous liners are dismantled and parts recycled.

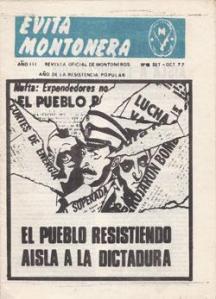

The novel is predominantly a second person narrative addressed to Elijah, long after she has lost him, narrating the events of their meeting, her pursuit of the dinosaur fossils straight after meeting him, her return to Dhaka and then her escape from her family to Chittagong, to work alongside a female film-maker interviewing workers on the ship graveyards, beaches where enormous liners are dismantled and parts recycled. In The Rabbit House, Laura rarely refers to the political situation that forced them to live in hiding, resulting in her having to change her name and be extra careful about how she engaged with others, for it is written from the perspective of her 7-year-old self, exactly as she recalls the events and changes that occurred in their lives at the time, with little understanding of the cause of this sudden change.

In The Rabbit House, Laura rarely refers to the political situation that forced them to live in hiding, resulting in her having to change her name and be extra careful about how she engaged with others, for it is written from the perspective of her 7-year-old self, exactly as she recalls the events and changes that occurred in their lives at the time, with little understanding of the cause of this sudden change. The only people in the house are Diana, seven months pregnant, my mother behind the false back wall, and me.

The only people in the house are Diana, seven months pregnant, my mother behind the false back wall, and me. Further Reading

Further Reading

The cover is an apt metaphor of the book, where water plays a significant role in multiple turning points in the novel and the image of a woman half-submerged, reminds me of that ability a person has of appearing to cope and be present on and above the surface, when beneath that calm exterior, below in the murky depths, unseen elements apply pressure, disturbing the tranquil image.

The cover is an apt metaphor of the book, where water plays a significant role in multiple turning points in the novel and the image of a woman half-submerged, reminds me of that ability a person has of appearing to cope and be present on and above the surface, when beneath that calm exterior, below in the murky depths, unseen elements apply pressure, disturbing the tranquil image. We arrive in a hill city of Kandy in Sri Lanka where she recounts her solitary, yet idyllic childhood, among the scent of tropical gardens, a big old house, ‘sweeping emerald lawns leading down to the rushing river‘ overlooked by monsoon clouds.

We arrive in a hill city of Kandy in Sri Lanka where she recounts her solitary, yet idyllic childhood, among the scent of tropical gardens, a big old house, ‘sweeping emerald lawns leading down to the rushing river‘ overlooked by monsoon clouds.

I first read Haitian author, Edwidge Danticat last summer, her novel Breath, Eyes, Memory (review linked below) about a young girl living with her Aunt in Haiti, while her mother lived in New York, a little like the life of the author herself, much of which is revealed in this non-fiction title, Brother, I’m Dying where we learn more about her life, though the primary focus is on her father Mira and in particular, her Uncle Joseph.

I first read Haitian author, Edwidge Danticat last summer, her novel Breath, Eyes, Memory (review linked below) about a young girl living with her Aunt in Haiti, while her mother lived in New York, a little like the life of the author herself, much of which is revealed in this non-fiction title, Brother, I’m Dying where we learn more about her life, though the primary focus is on her father Mira and in particular, her Uncle Joseph.

It feels like I have been watching Lauren Groff from the sidelines for a long time. One of my favourite bloggers Cassie*, wrote a passionate review about Groff’s book of short stories Delicate, Edible Birds which she gave the byline

It feels like I have been watching Lauren Groff from the sidelines for a long time. One of my favourite bloggers Cassie*, wrote a passionate review about Groff’s book of short stories Delicate, Edible Birds which she gave the byline  I even took her novel The Monsters of Templeton out from the library, yes, they had a copy on the few English shelves of the French library, it sounded like a fun read, sort of Lochness monster-ish – however I didn’t get around to reading, I returned it and I visit it often when I get the inclination to go to the library, not because I need any more books, but because it’s one of the best places to view books – you know like shoppers go window shopping – book nerds visit libraries and book shops just to be around them, without always needing to consume.

I even took her novel The Monsters of Templeton out from the library, yes, they had a copy on the few English shelves of the French library, it sounded like a fun read, sort of Lochness monster-ish – however I didn’t get around to reading, I returned it and I visit it often when I get the inclination to go to the library, not because I need any more books, but because it’s one of the best places to view books – you know like shoppers go window shopping – book nerds visit libraries and book shops just to be around them, without always needing to consume. Then there was Arcadia, I have it on kindle and have been meaning to read that too – a hippy story from the 1960’s – that too languishes unread.

Then there was Arcadia, I have it on kindle and have been meaning to read that too – a hippy story from the 1960’s – that too languishes unread. first half is about Lotto (nickname for Lancelot), a man cruising through life without looking back, the very few times he does, he realises how alone he really is. It is not a pleasant feeling, it is one he wishes to drown in whatever is to hand – in his boarding school that feeling nearly did kill him, but then he discovered girls, a never-ending supply of them, that worked – then he met Mathilde and she provoked in him such a strong feeling, he made her his wife, she was all the girl he wanted and needed and she appeared to need him as much as he needed her. She was hungry for him too.

first half is about Lotto (nickname for Lancelot), a man cruising through life without looking back, the very few times he does, he realises how alone he really is. It is not a pleasant feeling, it is one he wishes to drown in whatever is to hand – in his boarding school that feeling nearly did kill him, but then he discovered girls, a never-ending supply of them, that worked – then he met Mathilde and she provoked in him such a strong feeling, he made her his wife, she was all the girl he wanted and needed and she appeared to need him as much as he needed her. She was hungry for him too. also chose a book about marriage, one I think might be more my cup of tea, it was the poet Elizabeth Alexander’s memoir The Light of the World, a woman writing about being at the existential crossroads after the death of her husband.

also chose a book about marriage, one I think might be more my cup of tea, it was the poet Elizabeth Alexander’s memoir The Light of the World, a woman writing about being at the existential crossroads after the death of her husband.