A popular book in 2017, it won the Costa Book Award and has gone on to become a bestseller and will become a film starring Reese Witherspoon (who acquired the film rights), an incredible success for the debut novel of Gail Honeyman. To be honest, it hadn’t been on my radar, however when a friend lent me her copy, insisting I read it and a rainy day beckoned, I turned the page…

The book begins with an interesting quote from Olivia Laing’s book The Lonely City:

“…loneliness is hallmarked by an intense desire to bring the experience to a close; something which cannot be achieved by getting out more, but only by developing intimate connections. This is far easier said than done, especially for people whose loneliness arises from a state of loss or exile or prejudice, who have reason to fear or mistrust as well as long for the society of others.”

Eleanor Oliphant has been in the same office job in Glasgow, Scotland for almost eight years, she’s in her late twenties, intelligent, observant and diligent, she likes and needs routine and copes fine with her lack of social engagement, lack of friends, lack of family – with the exception of a weekly conversation with her mother on Wednesdays – and seems not to feel anything even when she overhears her colleagues speaking unkindly behind her back.

So used to her self imposed isolation and predictable life is she, that she seems shocked when a new employee Raymond from IT, whom she calls when her computer freezes one morning, initiates conversation with her outside the office, speaking to her as if she might be just like the others.

So used to her self imposed isolation and predictable life is she, that she seems shocked when a new employee Raymond from IT, whom she calls when her computer freezes one morning, initiates conversation with her outside the office, speaking to her as if she might be just like the others.

In this introduction to Eleanor, we aren’t sure of her, though her obvious intelligence and comfort in routine, he slight air of superiority despite the comments of her colleagues, suggest some kind of cognitive difference and her lack of a filter or self-censoring ability make her abject honesty a cause of surprise to some. Her habit of consuming vast amounts of vodka at home alone at the weekend, suggest something more dire lurks in her past.

Over the course of the novel, more of her early life is revealed and we learn that she has been through some kind of childhood trauma, which might explain some of her behaviours. This really sets up what for me was the main question, was this a case of nature, nurture (lack of) or trauma or a combination of them all. Honeyman leaves it to the reader to decide, but regardless of what influences made Eleanor the way she is, she is ripe for transformation. And she seems to have realised it herself, albeit, lead by a new obsession.

For, at the same time, and from the opening pages, she believes she may have met the perfect man, or is about to meet him, she obsesses about this man and builds him into her image of perfection, as had been defined by her absent mother, and prepares to improve herself physically in preparation of meeting him.

Meanwhile, through Raymond, her actual social connections begin to widen and they awaken something familiar in her, feelings that go with being invited to be part of a community, small acts of kindness, of inclusiveness, and Raymond helps her navigate these interactions, as might a friend.

It is a well written, engaging and thought provoking read, partly because of what is not known and slowly revealed, but the dialogue gives the story pace and there are plenty of new activities and social interactions Eleanor participates in, providing the space for her to grow and develop within.

“I wondered how it would feel to perform such simple deeds for other people. I couldn’t remember. I had done such things in the past, tried to be kind, tried to take care, I knew I had, but that was before. I tried, and I had failed, and all was lost to me afterwards. I had no one to blame but myself.”

I did find the character of Eleanor a little difficult to believe in, the long years of solitude followed by a relatively sudden transformation seem to occur too easily and quickly, however if I were to suspend judgement on the authenticity of the character and the speed of her life change, which wasn’t hard to do, then it becomes a kind of coming-of-age novel about a young woman overcoming a traumatic past and demonstrates (a little too conveniently) the healing that can come from genuine friendship and being part of a family and community and a functional workplace (if there is such a thing).

I did find the character of Eleanor a little difficult to believe in, the long years of solitude followed by a relatively sudden transformation seem to occur too easily and quickly, however if I were to suspend judgement on the authenticity of the character and the speed of her life change, which wasn’t hard to do, then it becomes a kind of coming-of-age novel about a young woman overcoming a traumatic past and demonstrates (a little too conveniently) the healing that can come from genuine friendship and being part of a family and community and a functional workplace (if there is such a thing).

The introduction of a therapist also allows for the conversations that explore the difference between the fulfillment of physical needs and emotional needs, neatly tying things up and rounding off Eleanor’s late education and self development.

And while it’s not exactly a romance, there are elements of the ambiguity of her friendship with Raymond that certainly are likely to make this a popular film.

An entertaining, light read, that leaves you with more than a few questions.

Nine strangers, each in different ways, become summoned by trees, brought together in a last stand to save the continent’s few remaining acres of virgin forest. The Overstory unfolds in concentric rings of interlocking fable, ranging from antebellum New York to the late-twentieth-century Timber Wars of the Pacific Northwest and beyond, revealing a world alongside our own — vast, slow, resourceful, magnificently inventive and almost invisible to us. This is the story of a handful of people who learn how to see that world, and who are drawn up into its unfolding catastrophe.

Nine strangers, each in different ways, become summoned by trees, brought together in a last stand to save the continent’s few remaining acres of virgin forest. The Overstory unfolds in concentric rings of interlocking fable, ranging from antebellum New York to the late-twentieth-century Timber Wars of the Pacific Northwest and beyond, revealing a world alongside our own — vast, slow, resourceful, magnificently inventive and almost invisible to us. This is the story of a handful of people who learn how to see that world, and who are drawn up into its unfolding catastrophe. Walker is a D-Day veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder; he can’t return home to rural Nova Scotia, and looks instead to the city for freedom, anonymity and repair. As he moves from New York to Los Angeles and San Francisco we witness a crucial period of fracture in American history, one that also allowed film noir to flourish. The Dream had gone sour but — as those dark, classic movies made clear — the country needed outsiders to study and dramatise its new anxieties. While Walker tries to piece his life together, America is beginning to come apart: deeply paranoid, doubting its own certainties, riven by social and racial division, spiralling corruption and the collapse of the inner cities. The Long Take is about a good man, brutalised by war, haunted by violence and apparently doomed to return to it — yet resolved to find kindness again, in the world and in himself.

Walker is a D-Day veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder; he can’t return home to rural Nova Scotia, and looks instead to the city for freedom, anonymity and repair. As he moves from New York to Los Angeles and San Francisco we witness a crucial period of fracture in American history, one that also allowed film noir to flourish. The Dream had gone sour but — as those dark, classic movies made clear — the country needed outsiders to study and dramatise its new anxieties. While Walker tries to piece his life together, America is beginning to come apart: deeply paranoid, doubting its own certainties, riven by social and racial division, spiralling corruption and the collapse of the inner cities. The Long Take is about a good man, brutalised by war, haunted by violence and apparently doomed to return to it — yet resolved to find kindness again, in the world and in himself. Due to an ugly scandal involving allegations of sexual harassment and corruption, there was no Nobel Prize for Literature awarded in 2018. Apparently it will resume next year, however to fill the gap, an alternative prize was awarded by

Due to an ugly scandal involving allegations of sexual harassment and corruption, there was no Nobel Prize for Literature awarded in 2018. Apparently it will resume next year, however to fill the gap, an alternative prize was awarded by

‘The story is, of course, about my grandmother but the real problem was my mother. I lost my mother when I was very young — fourteen and a half. And during the short time that I knew her I could never understand her. She was a very complex character. Some people — most people, the majority of people — disliked her. They believed she was too arrogant, too choleric. But we knew at home that she was the most sensitive person and I could not understand that contradiction between the way she looked and the way she actually was. So I tried to understand as I grew up and I discovered that it was because of a big problem with her own mother. She seems to have failed; she had the feeling that she was not a good, dutiful daughter. I had to understand the grandmother and the relationship between my mother, Jeanne, and her mother, Victoire, to understand who Jeanne was, why she was the way she was, and at the same time understand myself.’

‘The story is, of course, about my grandmother but the real problem was my mother. I lost my mother when I was very young — fourteen and a half. And during the short time that I knew her I could never understand her. She was a very complex character. Some people — most people, the majority of people — disliked her. They believed she was too arrogant, too choleric. But we knew at home that she was the most sensitive person and I could not understand that contradiction between the way she looked and the way she actually was. So I tried to understand as I grew up and I discovered that it was because of a big problem with her own mother. She seems to have failed; she had the feeling that she was not a good, dutiful daughter. I had to understand the grandmother and the relationship between my mother, Jeanne, and her mother, Victoire, to understand who Jeanne was, why she was the way she was, and at the same time understand myself.’ She set off, not just in search of grandmothers and great grandmothers, but in search of the Kingdom of Segu, about which write an incredible historical novel,

She set off, not just in search of grandmothers and great grandmothers, but in search of the Kingdom of Segu, about which write an incredible historical novel,

The reason they are highlighted in August is an attempt to raise awareness of the very narrow choice we give ourselves by only reading books in English, or from one’s own country and to highlight the fact that even when we do read outside our first language, the majority of books published, promoted and reviewed are written by men.

The reason they are highlighted in August is an attempt to raise awareness of the very narrow choice we give ourselves by only reading books in English, or from one’s own country and to highlight the fact that even when we do read outside our first language, the majority of books published, promoted and reviewed are written by men.

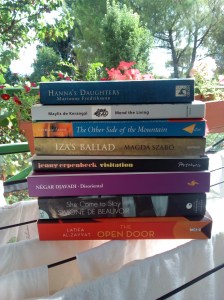

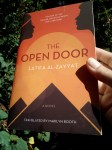

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir

She Came to Stay by Simone de Beauvoir Hanna has one daughter, Johanna, a name that carries its own story and past, before she is even born, one of the reasons she is closer to her father in her early years. Johanna would also have one daughter Anna, it is she who begins to narrate this story, she visits her mother in hospital, desperate to get answers to questions she has left it too late to ask.

Hanna has one daughter, Johanna, a name that carries its own story and past, before she is even born, one of the reasons she is closer to her father in her early years. Johanna would also have one daughter Anna, it is she who begins to narrate this story, she visits her mother in hospital, desperate to get answers to questions she has left it too late to ask. The first half of the book is dedicated to Hanna and her life and this is where the novel is at its best, immersed in the struggle of Hanna’s early years, its tragic turning point and the situation she is forced to accept as a result. Circumstances that will become buried deep, that nevertheless leave their impression on how she is in the world and impact those daughters indirectly.

The first half of the book is dedicated to Hanna and her life and this is where the novel is at its best, immersed in the struggle of Hanna’s early years, its tragic turning point and the situation she is forced to accept as a result. Circumstances that will become buried deep, that nevertheless leave their impression on how she is in the world and impact those daughters indirectly.

The Other Side of the Mountain by Erendiz Atasü is one of those books I came across in a blog post I read in 2017, a post entitled

The Other Side of the Mountain by Erendiz Atasü is one of those books I came across in a blog post I read in 2017, a post entitled

Antoine Laurain is one of my go to author’s when I’m in the mood for something short and light and of course, being a French author, there’s going to be the inevitable addition of the little French quirks, the things that one recognises from living here in France for more than 10 years.

Antoine Laurain is one of my go to author’s when I’m in the mood for something short and light and of course, being a French author, there’s going to be the inevitable addition of the little French quirks, the things that one recognises from living here in France for more than 10 years. After a series of stressful events overwhelm him, he takes up the habit once more, relieved to find that the ‘urge’ has returned, but shocked to discover that the subsequent ‘pleasure’ that should follow it when he does light up has gone. Angered and determined to have that aspect returned to him, he makes a follow-up appointment with the hypnotist to reverse the procedure, which will lead him down a rocky road towards involvement in a worse crime, in pursuit of that elusive ‘pleasure’ he is determined to retrieve.

After a series of stressful events overwhelm him, he takes up the habit once more, relieved to find that the ‘urge’ has returned, but shocked to discover that the subsequent ‘pleasure’ that should follow it when he does light up has gone. Angered and determined to have that aspect returned to him, he makes a follow-up appointment with the hypnotist to reverse the procedure, which will lead him down a rocky road towards involvement in a worse crime, in pursuit of that elusive ‘pleasure’ he is determined to retrieve.

He introduces us to the Luminous Healers, significant teachers and mentors he had during his time with the Native American shamans and puts historical references into a modern context. It is incredible that any of these beliefs and practices have survived after the destruction of the Indians by early settlers, which obliterated the spiritual traditions of most native groups. Native American shamans were reluctant to share their heritage with white people.

He introduces us to the Luminous Healers, significant teachers and mentors he had during his time with the Native American shamans and puts historical references into a modern context. It is incredible that any of these beliefs and practices have survived after the destruction of the Indians by early settlers, which obliterated the spiritual traditions of most native groups. Native American shamans were reluctant to share their heritage with white people.