It feels a little fraudulent to write about my favourite reads of 2022, when I forbid myself to read or write about books for six months of the year, while I was working on a creative writing project. Writing about books is one of my greatest pleasures, however I realised that if I could harness that energy and apply it to something else I wished to complete, perhaps I could finish that other project.

I did finish it, so I’m giving myself a break and reopening the blog door, keeping the ‘thoughts on books’ muscle active.

An Irish Obsession and A Foreign Language Desire

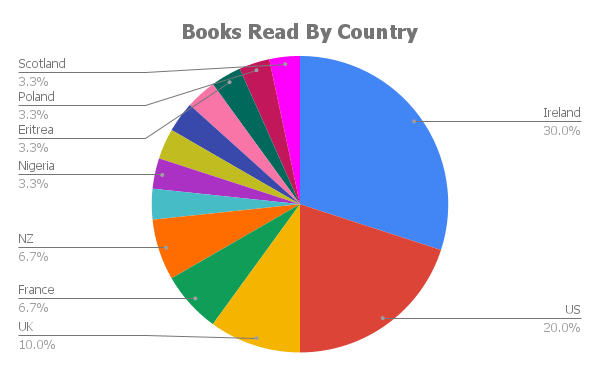

Though I read less than half the number of books of 2021, I did manage to read 30 books from 13 countries, a third Irish authors, thanks to Cathy’s annual Reading Ireland month in February. I’m looking forward to more Irish reads this year; there were many promising reads published in 2022 that I wasn’t able to get to.

Though I read less than half the number of books of 2021, I did manage to read 30 books from 13 countries, a third Irish authors, thanks to Cathy’s annual Reading Ireland month in February. I’m looking forward to more Irish reads this year; there were many promising reads published in 2022 that I wasn’t able to get to.

Sadly I missed Women in Translation month in August, though I managed to read six books in translation, two making my top reads of the years.

2023 will definitely be better for translations, since I’ve taken out a Charco Press subscription, giving me the opportunity to read a few Latin American contemporary authors from Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia and Mexico.

Non-Fiction, A Rival to the Imagination

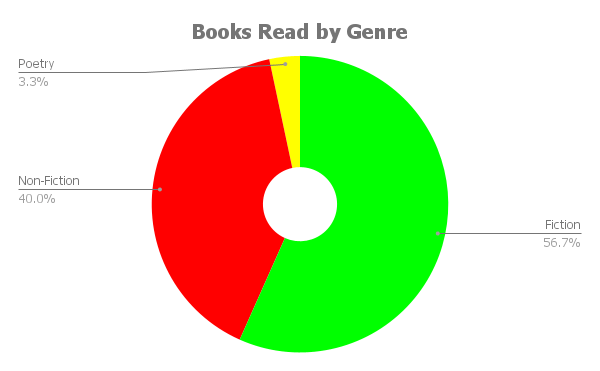

As far as genre went, there was a much greater balance between fiction and non-fiction than in previous years, due to having been in the mood to read a lot more non-fiction this year.

And so to the books that left the most significant impression, where I have reviewed them I’ll create a link in the title.

One Outstanding Read

Was there one book that could claim the spot of Outstanding Read of 2022? This wasn’t easy to decide given most of my reading occurred in the beginning of the year, but as I look over the titles, there was one book that I remember being pleasantly surprised by and having that feeling of it not wanting to end, and being laugh out loud funny in places.

It is one of those novels, or perhaps I ought to say she is one of those writer’s whose works I wouldn’t mind being stuck on a desert island with, more than just a story, they open your mind to other works, stimulate curiosity and have a particular sensibility that reassures this reader that the novel will endure.

“I absolutely loved it and was surprised at how accessible a read it was, given this is an author who recently won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Her power to provoke by telling a story is only heightened by the suggestion on the back cover that her ideas presented here caused a genuine political uproar in Poland.” – extract from my review

So here it is, my One Outstanding Read of 2022 was :

Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead translated from Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

In no particular order, here are my top 5 fiction and non-fiction reads for 2022.

Top 5 Fiction

Marzhan, mon amour, Katja Oskamp (Germany) translated by Jo Heinrich

Marzhan, mon amour, Katja Oskamp (Germany) translated by Jo Heinrich

– What a joy this Peirene novella was, one of those rare gems of what I perceived as uplifting fiction, until I lent it to a friend who is a nurse, who DNF’d it, making me realise that what can be delightful for one reader can be quite the opposite for another, in this case, someone who had heard too many sad stories from patients, requiring an empathetic barrier, to endure the overwhelm it creates.

Marzhan is a much maligned multi-storied, communist-era, working class quarter in East Berlin, where our protagonist, a writer, leaves her career behind to retrain as a chiropodist, due to the sudden illness of her husband. In each chapter, we meet one of her clients, members of the local community, many who have lived there since its construction 40 years earlier. A chronicler of their personal histories, we witness the humanity behind the monolith structures of the housing estates, the connections created between the three women working in the salon and the warmth and familiarity they provide to those who cross their threshold. A semi-autobiographical gem.

The Last Resort, Jan Carson (Northern Ireland)

The Last Resort, Jan Carson (Northern Ireland)

– Another novella, this was another delightful, often hilarious story, with well constructed characterisation. Set in a fictional Seacliff caravan park in Ballycastle on the North Coast of Ireland, a group gather to place a memorial bench on the cliff top for a departed friend.

Each chapter is narrated by one of 10 characters, revealing their state of mind and concerns, while exploring complex family dynamics, ageing, immigration, gender politics, the decline of the Church and the legacy of the Troubles. A sense of mystery and suspense, pursued by teenage sleuth Alma, lead to the final scene, the cliff-hanger. A delightful afternoon romp.

I Will Die in a Foreign Land, Kalani Pickhart (US) (Set in Ukraine 2013/14) (Historical Fiction)

I Will Die in a Foreign Land, Kalani Pickhart (US) (Set in Ukraine 2013/14) (Historical Fiction)

– Set in Ukraine in 2014, during the Euromaiden protests, four characters with different backgrounds (two outsiders, two protestors) cross paths, share histories, traverse geography and represent different perspectives in this Revolution of Dignity, the origin of a conflict that endures today.

The narrative is gripping, informative, well researched and had me veering off to look up numerous historical references. Moved by the documentary, Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Democracy, Pickhart was struck by the fighting spirit of the Ukrainian people against their government and the echo of the past, when the bells of St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery rang for the first time since the Mongols invaded Kyiv in 1240AD.

“Though it is novel told in fragments, through multiple narratives and voices, there is a fluidity and yet the plot moves quickly, as the connection(s) between characters are revealed, their motivations and behaviours come to be understood and revelations acknowledge the pressures and complexities of life in this country, some things universal, others unique to their history and geography.”

Nora, A Love Story of Nora Barnacle & James Joyce, Nuala O’Connor (Ireland) (Historical Fiction)

Nora, A Love Story of Nora Barnacle & James Joyce, Nuala O’Connor (Ireland) (Historical Fiction)

– Absolutely loved it. I was instantly transported into Nora’s world, seeing their life and travels, the many challenges they faced and the unique connection that kept them together throughout. I knew nothing of their lives before picking this up during the One Dublin, One Book initiative in April 2022. Knowing now all the many places they lived and how Europe allowed them to live free of convention, I’m curious to encounter the stories Joyce created while Nora was keeping everything else together for him.

It is incredible that Nuala O’Connor managed to put together such a cohesive story given the actions of Joyce’s formidable grandson/gatekeeper Stephen, who did all he could to prevent access or usage of the family archive, including the destruction of hundreds of letters, until his death in 2020.

In 2023 the One Dublin, One Book read will be The Coroner’s Daughter by Andrew Hughes.

Towards Another Summer, Janet Frame (NZ) (Literary Fiction)

Towards Another Summer, Janet Frame (NZ) (Literary Fiction)

– What a treat this was, one of Janet Frame’s early novels written in the 1960’s when she was living in London, one she was too self conscious to allow to be published, so it came out posthumously in 2007. Written long before any of her autobiographical work, it clearly was inspired by much of her own experience as a writer more confident and astute with her words on the page than social graces.

In the novel, a young NZ author living in a studio in London, is invited to spend a weekend with a journalist and his family, something she looks forward to until beset by anxiety and awkwardness. Her visit is interspersed with reminiscences of her homeland, of a realisation of her homesickness and desire to return. She imagines herself a migratory bird, a kind of shape-shifting ability that helps her to be present, absent, to cope with the situation and informs her writing.

“A certain pleasure was added to Grace’s relief at establishing herself as a migratory bird. She found that she understood the characters in her novel. Her words flowed, she was excited, she could see everyone and everything.”

Top 5 Non-Fiction

All About Love: New Visions, bell hooks (US)

All About Love: New Visions, bell hooks (US)

– What a joy it was to discover the voice and beautifully evolved mind of bell hooks in these pages.

Her perspective is heart lead, her definition of love leaves behind conditioned perceptions of romance and desire and the traditional roles of carer, nurturer, provider – and suggests that it might be ‘the will to do for oneself or another that which enables us to grow and evolve spiritually’ love becomes a verb not a noun.

It is a way of looking at this least discussed human emotion and activity that fosters hope and encouragement, in an era where we have been long suffering the effects of lovelessness under a societal system of domination.

The Passenger – Ireland (Essays, Art, Investigative Journalism)

The Passenger – Ireland (Essays, Art, Investigative Journalism)

– This collection of essays, art and information about contemporary Ireland is an underrated gem! Europa Editions noticed my prolific reading around Ireland after I read Sara Baume’s wonderful A Line Made By Walking and mentioned that she was one of the contributors to this stunning collection.

I planned to read a couple of essays each day, but it was so interesting, I kept reading until I finished it. Brilliant!

Across 11 essays, the collection explores the life and times of modern Ireland, with contributions from Catherine Dunne and Caelinn Hogan – discussing the decline of the Church’s influence, the dismantling of a system designed to oppress women and a culture of silence in The Mass is Ended; William Atkins writes a fascinating essay on the Boglands; Manchan Magnan shares how the contraction of a small local fishing industry heralded the decline and disappearance of much of the Irish language in An Ocean of Wisdom; Sara Baume writes of Talismans and Colum McCann of nostalgia in Everything That Falls Must Also Rise.

The BBC’s former political editor in Northern Ireland Mark Devenport, writes about a region hanging in the balance, the UK and the EU, torn between fear and opportunity and the distinct feeling of having been abandoned in At The Edge of Two Unions: Northern Ireland’s Causeway Coast; while Lyra McKee’s gut-wrenching essay Suicides of the Ceasefire Babies investigates the troubling fact that since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, more people in Northern Ireland have committed suicide than were killed during the 30 year conflict.

“Intergenerational transmission of trauma is not just a sociological or psychological problem, but also a biological one.”

And more, a brilliant essay on citizen assemblies, another on Irish music, rugby and a less enchanting one that explores locations in The Game of Thrones.

What My Bones Know, A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma, Stefanie Foo (US) (Memoir)

What My Bones Know, A Memoir of Healing from Complex Trauma, Stefanie Foo (US) (Memoir)

– This was a gripping memoir I couldn’t put down. I read it for reference purposes, interested in the solutions she finds for healing complex PTSD. It is well researched, while each section contributes to the arc of a comprehensive and compelling narrative.

Stefanie Foo had a dream job as an award-winning radio producer at This American Life and was in a loving relationship. But behind her office door, she was having panic attacks and sobbing at her desk every morning. After years of questioning what was wrong with herself, she was diagnosed with complex PTSD – a condition that occurs when trauma happens continuously, over the course of years.

She becomes the subject of her own research, her journalist skills aiding her to interview those responsible for various discoveries and healing modalities, gaining insights into the effect and management of her condition, eventually reclaiming agency over it.

“Every cell in my body is filled with the code of generations of trauma, of death, of birth, of migration, of history that I cannot understand. . . . I want to have words for what my bones know.”

Ancestor Trouble, A Reckoning & A Reconciliation, Maud Newton (US) (Memoir/Genealogy)

Ancestor Trouble, A Reckoning & A Reconciliation, Maud Newton (US) (Memoir/Genealogy)

– This was a fascinating read and exploration, at the intersection between family history and genetics; the author sets out to explore the nurture versus nature question with the aid of DNA genetic reports and stories both documented about and passed down through her family. Some of those stories and people she was estranged from create a concern/fear about what she might inherit.

Maud Newton explores society’s experiments with eugenics pondering her father’s marriage, a choice he made based on trying to create “smart kids”. She delves into persecuted women, including a female relative accused of being a witch, and discovers a clear line of personality inclinations that have born down the female line of her family. A captivating and highly informative read.

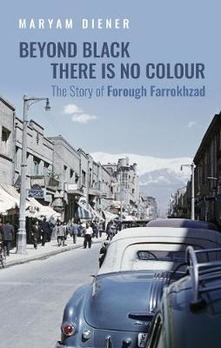

My Father’s Daughter, Hanna Azieb Pool (UK/Eritrea) (Adoptee Memoir)

My Father’s Daughter, Hanna Azieb Pool (UK/Eritrea) (Adoptee Memoir)

– A memoir of the Eritrean-British journalist, Hannah Azieb-Pool, who returns to Eritrea at the age of 30 to meet her family for the first time. In her twenties, Azieb-Pool is given a letter that unravels everything she knows about her life. Adopted from an orphanage in Eritrea, brought to the UK, it was believed she had no surviving relatives. When she discovers the truth in a letter from her brother – that her birth father is alive and her Eritrean family are desperate to meet her, she is confronted with a decision and an opportunity, to experience her culture origins and meet her family for the first time.

It’s a story of uncovering the truth, of making connections, a kind of healing or reconciliation. Ultimately what has been lost can never be found. It’s like she was able to view an image of who she might have been and the life she may have had, and while viewing it was cathartic, it is indeed an illusion, a life imagined, one never possible to live.

* * * * * *

Have you read any of these books? Anything here tempt you for reading in 2023?

Happy Reading All!

Told through the eyes of a 14-year-old boy subjected to relentless bullying, Heaven is a haunting novel of the threat of violence that can stalk our teenage years.

Told through the eyes of a 14-year-old boy subjected to relentless bullying, Heaven is a haunting novel of the threat of violence that can stalk our teenage years. A unique story that interweaves crime fiction with intimate tales of morality and the search for individual freedom.

A unique story that interweaves crime fiction with intimate tales of morality and the search for individual freedom. Jon Fosse delivers both a transcendent exploration of the human condition and a radically ‘other’ reading experience – incantatory, hypnotic, and utterly unique.

Jon Fosse delivers both a transcendent exploration of the human condition and a radically ‘other’ reading experience – incantatory, hypnotic, and utterly unique. An urgent yet engaging protest against the destructive impact of borders, whether between religions, countries or genders.

An urgent yet engaging protest against the destructive impact of borders, whether between religions, countries or genders. Olga Tokarczuk’s portrayal of Enlightenment Europe on the cusp of precipitous change, searching for certainty and longing for transcendence.

Olga Tokarczuk’s portrayal of Enlightenment Europe on the cusp of precipitous change, searching for certainty and longing for transcendence. Bora Chung presents a genre-defying collection of short stories, which blur the lines between magical realism, horror and science fiction.

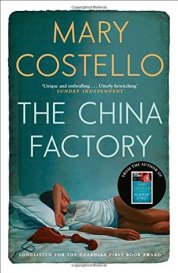

Bora Chung presents a genre-defying collection of short stories, which blur the lines between magical realism, horror and science fiction. I’ve heard many say good things about her debut novel Academy Street and when her most recent novel The River Capture was published, a self-confessed homage to James Joyce’s Ulysses, I decided I would start at the beginning with Costello’s short stories.

I’ve heard many say good things about her debut novel Academy Street and when her most recent novel The River Capture was published, a self-confessed homage to James Joyce’s Ulysses, I decided I would start at the beginning with Costello’s short stories.

Mary Costello is an Irish short story writer and novelist from Galway now living in Dublin.

Mary Costello is an Irish short story writer and novelist from Galway now living in Dublin. Somewhere on a plateau above a small forested village in Poland, near the border with the Czech Republic, lives Janina, except she doesn’t like that name, she insists on being called Mrs Duszejko.

Somewhere on a plateau above a small forested village in Poland, near the border with the Czech Republic, lives Janina, except she doesn’t like that name, she insists on being called Mrs Duszejko.

Dizzy, a former student, now her 30 year old friend, helps with the Blake translations, though is unconvinced by some of her theories concerning astrology and the revenge of animals, bolstered by her having discovered real animal trials, which peaked in 14th to 16th century Europe.

Dizzy, a former student, now her 30 year old friend, helps with the Blake translations, though is unconvinced by some of her theories concerning astrology and the revenge of animals, bolstered by her having discovered real animal trials, which peaked in 14th to 16th century Europe. When he challenges her for going around telling people about those Animals, concerned for her reputation, she is outraged.

When he challenges her for going around telling people about those Animals, concerned for her reputation, she is outraged. Olga Tokarczuk is an Aquarian, a Psychologist and Jungian expert, a Polish essayist and author of nine novels, three short story collections and her work has been translated into forty-five languages.

Olga Tokarczuk is an Aquarian, a Psychologist and Jungian expert, a Polish essayist and author of nine novels, three short story collections and her work has been translated into forty-five languages. As mentioned in

As mentioned in  1.

1.  2.

2.  3.

3.  4.

4.  5.

5.  6.

6.  7.

7.  8.

8.  9.

9.  10.

10.  I loved how this historical novel focuses on the lives of these women, Rue her mother May Belle and grandmother Ma Doe and the community within which they live, without allowing the narrative to stray over too far into the lives and homes of those who diminished their lives.

I loved how this historical novel focuses on the lives of these women, Rue her mother May Belle and grandmother Ma Doe and the community within which they live, without allowing the narrative to stray over too far into the lives and homes of those who diminished their lives.

In May Belle’s time, one of the ways to effect a conjure was to make a doll that bore a resemblance to the person and if possible to access strands of hair to entwine with whatever material was used. Varina has porcelain dolls that Rue admires and is envious of, when she discovers her mother is making a doll that faintly resembles her, she pretends not to notice she has discovered it, and will mask even further her disappointment when she misreads its purpose.

In May Belle’s time, one of the ways to effect a conjure was to make a doll that bore a resemblance to the person and if possible to access strands of hair to entwine with whatever material was used. Varina has porcelain dolls that Rue admires and is envious of, when she discovers her mother is making a doll that faintly resembles her, she pretends not to notice she has discovered it, and will mask even further her disappointment when she misreads its purpose.

Pearl has promised the Reverend to welcome this newcomer, but she wasn’t expecting the shock of seeing Sugar’s face and who it reminds her of, nor the sudden flurry of visitors who want to sit in her kitchen in case they get a peek at this unwelcome new resident, whom they’re so inquisitive of.

Pearl has promised the Reverend to welcome this newcomer, but she wasn’t expecting the shock of seeing Sugar’s face and who it reminds her of, nor the sudden flurry of visitors who want to sit in her kitchen in case they get a peek at this unwelcome new resident, whom they’re so inquisitive of. Bernice L. McFadden is the author of ten critically acclaimed novels including Sugar, Loving Donovan, Nowhere Is a Place, The Warmest December, Gathering of Waters (a New York Times Editors’ Choice and one of the 100 Notable Books of 2012), and Glorious, which was featured in O, The Oprah Magazine and was a finalist for the NAACP Image Award.

Bernice L. McFadden is the author of ten critically acclaimed novels including Sugar, Loving Donovan, Nowhere Is a Place, The Warmest December, Gathering of Waters (a New York Times Editors’ Choice and one of the 100 Notable Books of 2012), and Glorious, which was featured in O, The Oprah Magazine and was a finalist for the NAACP Image Award.

In a sense that too is at the heart of Transcendent Kingdom, a family from Ghana immigrate to the US, the mother, the father (who the narrator, the daughter Gifty, the only one of the family born in the US, refers to as Chin Chin man), and their son Nana. Though they leave their country behind, something of remains in them, and though they are determined to ascend in their new country, it comes at a price.

In a sense that too is at the heart of Transcendent Kingdom, a family from Ghana immigrate to the US, the mother, the father (who the narrator, the daughter Gifty, the only one of the family born in the US, refers to as Chin Chin man), and their son Nana. Though they leave their country behind, something of remains in them, and though they are determined to ascend in their new country, it comes at a price.

Yaa Gyasi was born in Mampong, Ghana and raised in Huntsville, Alabama. Her first novel, Homegoing, was a Sunday Times and New York Times bestseller, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Best First Novel and was shortlisted for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction.

Yaa Gyasi was born in Mampong, Ghana and raised in Huntsville, Alabama. Her first novel, Homegoing, was a Sunday Times and New York Times bestseller, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Best First Novel and was shortlisted for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction. A Passage North begins with a message from out of the blue: a telephone call informing Krishan that his grandmother’s caretaker, Rani, has died under unexpected circumstances. The news arrives soon after an email from Anjum, an impassioned yet aloof activist Krishnan fell in love with years before while living in Delhi, stirring old memories and desires from a world he left behind.

A Passage North begins with a message from out of the blue: a telephone call informing Krishan that his grandmother’s caretaker, Rani, has died under unexpected circumstances. The news arrives soon after an email from Anjum, an impassioned yet aloof activist Krishnan fell in love with years before while living in Delhi, stirring old memories and desires from a world he left behind. A woman invites a famed artist to visit the remote coastal region where she lives, in the belief that his vision will penetrate the mystery of her life and landscape. Over the course of one hot summer, his provocative presence provides the frame for a study of female fate and male privilege, of the geometries of human relationships, and of the struggle to live morally between our internal and external worlds.

A woman invites a famed artist to visit the remote coastal region where she lives, in the belief that his vision will penetrate the mystery of her life and landscape. Over the course of one hot summer, his provocative presence provides the frame for a study of female fate and male privilege, of the geometries of human relationships, and of the struggle to live morally between our internal and external worlds. The Promise charts the crash and burn of a white South African family, living on a farm outside Pretoria. The Swarts are gathering for Ma’s funeral. The younger generation, Anton and Amor, detest everything the family stand for, not least the failed promise to the Black woman who has worked for them her whole life. After years of service, Salome was promised her own house, her own land… yet somehow, as each decade passes, that promise remains unfulfilled.

The Promise charts the crash and burn of a white South African family, living on a farm outside Pretoria. The Swarts are gathering for Ma’s funeral. The younger generation, Anton and Amor, detest everything the family stand for, not least the failed promise to the Black woman who has worked for them her whole life. After years of service, Salome was promised her own house, her own land… yet somehow, as each decade passes, that promise remains unfulfilled. In the dying days of the American Civil War, newly freed brothers Landry and Prentiss find themselves cast into the world without a penny to their names. Forced to hide out in the woods near their former Georgia plantation, they’re soon discovered by the land’s owner, George Walker, a man still reeling from the loss of his son in the war.

In the dying days of the American Civil War, newly freed brothers Landry and Prentiss find themselves cast into the world without a penny to their names. Forced to hide out in the woods near their former Georgia plantation, they’re soon discovered by the land’s owner, George Walker, a man still reeling from the loss of his son in the war. From her place in the store, Klara, an Artificial Friend with outstanding observational qualities, watches carefully the behaviour of those who come in to browse, and those who pass in the street outside. She remains hopeful that a customer will soon choose her, but when the possibility emerges that her circumstances may change for ever, Klara is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans.

From her place in the store, Klara, an Artificial Friend with outstanding observational qualities, watches carefully the behaviour of those who come in to browse, and those who pass in the street outside. She remains hopeful that a customer will soon choose her, but when the possibility emerges that her circumstances may change for ever, Klara is warned not to invest too much in the promises of humans. Samuel has lived alone for a long time; one morning he finds the sea has brought someone to offer companionship and to threaten his solitude…

Samuel has lived alone for a long time; one morning he finds the sea has brought someone to offer companionship and to threaten his solitude… Clara’s sister is missing. Angry, rebellious Rose had a row with their mother, stormed out of the house and simply disappeared. Eight-year-old Clara, isolated by her distraught parents’ efforts to protect her from the truth, is grief-stricken and bewildered. Liam Kane, newly divorced, newly unemployed, newly arrived in this small northern town, moves into the house next door – a house left to him by an old woman he can barely remember — and within hours gets a visit from the police. It seems he’s suspected of a crime.

Clara’s sister is missing. Angry, rebellious Rose had a row with their mother, stormed out of the house and simply disappeared. Eight-year-old Clara, isolated by her distraught parents’ efforts to protect her from the truth, is grief-stricken and bewildered. Liam Kane, newly divorced, newly unemployed, newly arrived in this small northern town, moves into the house next door – a house left to him by an old woman he can barely remember — and within hours gets a visit from the police. It seems he’s suspected of a crime. A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to adoring fans, her entire existence overwhelmed by the internet — or what she terms ‘the portal’. Are we in hell? the people of the portal ask themselves. Who are we serving? Are we all just going to keep doing this until we die?

A woman known for her viral social media posts travels the world speaking to adoring fans, her entire existence overwhelmed by the internet — or what she terms ‘the portal’. Are we in hell? the people of the portal ask themselves. Who are we serving? Are we all just going to keep doing this until we die? Mahmood Mattan is a fixture in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay, 1952, which bustles with Somali and West Indian sailors, Maltese businessmen and Jewish families. A father, a chancer, a some-time petty thief, he is many things but not a murderer.

Mahmood Mattan is a fixture in Cardiff’s Tiger Bay, 1952, which bustles with Somali and West Indian sailors, Maltese businessmen and Jewish families. A father, a chancer, a some-time petty thief, he is many things but not a murderer. Theo Byrne is a promising young astrobiologist who has found a way to search for life on other planets dozens of light years away. The widowed father of an unusual nine-year-old, his son Robin is funny, loving and filled with plans. He thinks and feels deeply, adores animals and spends hours painting elaborate pictures. On the verge of being expelled from third grade for smashing his friend’s face with a metal thermos, this rare and troubled boy is being recommended psychoactive drugs.

Theo Byrne is a promising young astrobiologist who has found a way to search for life on other planets dozens of light years away. The widowed father of an unusual nine-year-old, his son Robin is funny, loving and filled with plans. He thinks and feels deeply, adores animals and spends hours painting elaborate pictures. On the verge of being expelled from third grade for smashing his friend’s face with a metal thermos, this rare and troubled boy is being recommended psychoactive drugs. Mehar, a young bride in rural 1929 Punjab, is trying to discover the identity of her new husband. She and her sisters-in-law, married to three brothers in a single ceremony, spend their days hard at work in the family’s ‘china room’, sequestered from contact with the men.

Mehar, a young bride in rural 1929 Punjab, is trying to discover the identity of her new husband. She and her sisters-in-law, married to three brothers in a single ceremony, spend their days hard at work in the family’s ‘china room’, sequestered from contact with the men. In 1920s Montana, wild-hearted orphan Marian Graves spends her days roaming the rugged forests and mountains of her home. When she witnesses the roll, loop and dive of two barnstorming pilots, she promises herself that one day she too will take to the skies.

In 1920s Montana, wild-hearted orphan Marian Graves spends her days roaming the rugged forests and mountains of her home. When she witnesses the roll, loop and dive of two barnstorming pilots, she promises herself that one day she too will take to the skies. Lunchtime on a Saturday, 1944: the Woolworths on Bexford High Street in South London receives a delivery of aluminum saucepans. A crowd gathers to see the first new metal in ages—after all, everything’s been melted down for the war effort. An instant later, the crowd is gone; incinerated. Among the shoppers were five young children.

Lunchtime on a Saturday, 1944: the Woolworths on Bexford High Street in South London receives a delivery of aluminum saucepans. A crowd gathers to see the first new metal in ages—after all, everything’s been melted down for the war effort. An instant later, the crowd is gone; incinerated. Among the shoppers were five young children.