Jamaica Kincaid’s The Autobiography of my Mother is a book that was being discarded from our local English library that I pounced on when I discovered it in the collection of books that hadn’t been borrowed for years and therefore must make way for others.

The 7 books I rescued from the Annual Library Sale!

I already have two slim novellas by the same author that sit unread, but something about this novel, for it is fiction, despite the playful title, insisted it should be read at once. Not just a fabulous cover, which is repeated inside as chapter headings, each chapter reveals a section of the photo, until the last one revealing the entire portrait – but the comments from various publications and writers who sang its praise back in 1996 when it was first published.

“Writing in precise, lyrical prose that uses the repetition of images and words to build a musical rhythm, Jamaica Kincaid conjures up the world of Dominica in all its beauty and casual cruelty, a world in which the magical coexists with the mundane, a world in which the ghosts of colonialism still haunt the relationships between men and women. In doing so she has written a powerful and disturbing book.” NEW YORK TIMES

And let me say from the outset, I absolutely loved this book, its language, its voice, its poetry, the complexity of its narrator, who could be so distant yet simultaneously get so under your skin. There is a raw but brutal honesty to it, that disturbs and is to be admired at the same time, it is so full of contrasts and so compelling and beats its rhythm so loud, I almost can’t describe it.

Now that I have finished it, I want to read more by Kincaid and just now before writing this review I looked up a little about the author’s own life, and now I am even more intrigued, what an amazing story and experiences which are often at the heart of what she channels through her stories. A unique voice indeed.

So for those who, like me, knew little about this author, a little background before talking about the novel.

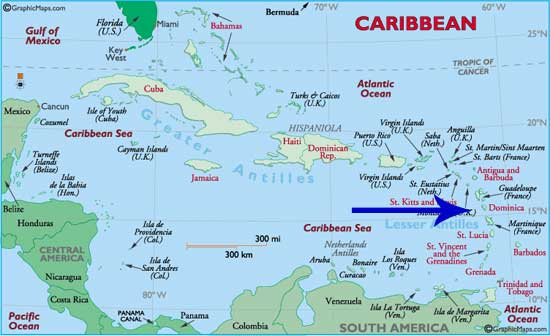

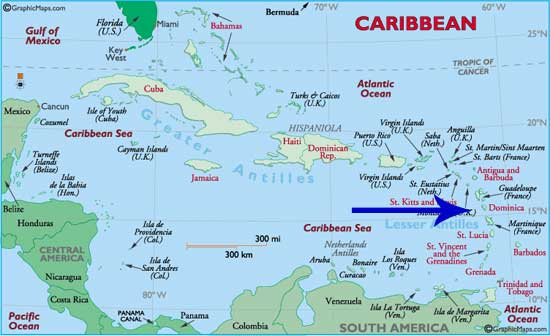

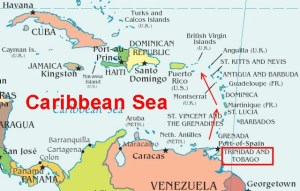

Jamaica Kincaid was born Elaine Potter Richardson in the capital city of St. John’s, Antigua in 1949. Antigua is a small island in the West Indies (a region of the Caribbean basin), colonised by the British in 1632 that became independent in 1981.

Her mother was from Dominica and her biological father, a West Indian chauffeur, whom she didn’t meet until her thirties. Kincaid was an only child until she was nine, when the first of her three brothers was born. Until then she’d had the sole attention of her mother, so life changed dramatically thereafter and at 17 she left for America, severing ties with her family and did not return to Antigua for 20 years, though it resonated deep within her creativity.

She still lives in the US today and teaches at Claremont McKenna College in Claremont, California. Her most recent novel See Now Then was published in 2013 after a 10 year absence, depicting in her original style the unravelling of an interracial marriage.

In the autobiography of my mother, we encounter Xuela Claudette Richardson, who narrates her life looking back over seventy years, though the sense of her life reads as if it is being lived in the present, so vivid are the memories, so visceral the experiences. Her mother died in child birth and her father left her with his laundry woman until she was seven, when he remarried and came back for her.

In the autobiography of my mother, we encounter Xuela Claudette Richardson, who narrates her life looking back over seventy years, though the sense of her life reads as if it is being lived in the present, so vivid are the memories, so visceral the experiences. Her mother died in child birth and her father left her with his laundry woman until she was seven, when he remarried and came back for her.

She recalls the moment vividly through the senses and how it made her feel.

“I thanked Eunice for taking care of me. I did not mean it, I could not mean it, I did not know how to mean it, but I would mean it now. I did not say goodbye; in the world that I lived in then and the world that I live in now goodbyes do not exist, it is a small world. All my belongings were in a muslin knapsack and he placed them in a bag that was on the donkey he had been riding. He placed me on the donkey and sat behind me. And this was how we looked as my back was turned on the small house in which I spent the first seven years of my life…”

Through the narrator looking back over years and at events that she re-experiences as she recalls them, we see how it was then, that something, whether it is the lack of maternal love or the makeup of this character, nature or nurture, contributes to her way of being in the world in an emotionally detached way. She responds to instincts and observes acutely her own responses and is able to look back on them and describe and account for them, but there is a sense of something missing, that appears through the recurring dream of a mother climbing up and away from her and the questions she asks herself throughout her life.

“Who was my father? Not just who was he to me, his child – but who was he? He was a policeman, but not an ordinary policeman; he inspired more than the expected amount of fear for someone in his position…At the time I came to live with him, he has just mastered the mask that he wore as a face for the remainder of his life: the skin taut, the eyes small and drawn back as though deep inside his head, so that it wasn’t possible to get a clue to him from them, his lips parted in a smile. He seemed trustworthy.”

Yet nothing is ever as it seems and she depicts her father as dishonest and grows up in a culture and environment of distrust, discouraged from making friendships, made to see that no one can be trusted.

“We were not friends; such a thing was discouraged. We were never to trust each other. This was like a motto repeated to us by our parents; it was a part of my upbringing, like a form of good manners: You cannot trust these people, my father would say to me, the very words the other children’s parents were saying to them, perhaps even at the same time. That “these people” were ourselves, that this insistence on mistrust of others – that people who looked so very much like each other, who shared a common history of suffering and humiliation and enslavement, should be taught to mistrust each other, even as children, is no longer a mystery to me. The people we should naturally have mistrusted were beyond our influence completely; what we needed to defeat them, to rid ourselves of them, was something far more powerful than mistrust. To mistrust each other was just one of many feelings we had for each other, all of them the opposite of love, all of them standing in the place of love.”

Her father’s wife who is resentful toward Xuela and reminds her often that she can’t be her father’s daughter, soon bears two children, a boy and a girl. Though there is no love between them, Xuela doesn’t hate her, she has sympathy for her.

“Her tragedy was greater than mine; her mother did not love her, but her mother was alive, and every day she saw her mother and every day her mother let her know she was not loved. My mother was dead.”

At 15, her father removes her from his home and takes her to live with a business partner and his wife as a boarder. She develops a close friendship with the wife, Madame LaBatte, observing with the same acuity their relationship and way of living and enters womanhood herself, observing and experiencing changes in her own body and the effect it elicits in others.

She makes decisions about her own womanhood, about her body, about mothering. And she lives her life in accordance with those decisions. She marries, she discovers love and seems never to lose that ability to see through the illusions that surround all those things without sacrificing pleasure and contentedness.

“And this man I married was one of the victors, and so much a part of him was this situation, the situation of the conqueror, that only through a book of history could he be reminded of a time when he might have been something other, something like me, the vanquished, the defeated. When he looked at the night sky, it was closed off; so, too, was the midday sky, closed off; the seas were closed off, the ground on which he walked was closed off. He did not have a future, he had only the past, he lived in that way; it was not a past he was responsible for all by himself, it was a past he had inherited. He did not object to his inheritance; it was a good one, only it did not bring happiness; and his reply to such an assertion would be the correct one: What can bring happiness? At the moment the conqueror asks such a question, his defeat is secure.”

And at the end I ask, who is writing this story? Who is this mother who had no mother and no children? And in the dying pages, she will answer the question and we may realise we knew it all along.

the autobiography of my Mother plumbs the depths of maternal love and its lack, mother daughter relationships, self-love, absent fathers and the latent influences of enslavement and occupation, how they continue to distort reality even when they are no longer present.

I find it almost impossible to describe the reading experience, except that it left me asking “How did I not know about this book?” The voice is so unique and powerful and much more than an imagination, it is rooted in something strong and yet transparent and is utterly compelling. Don’t read this for story, this is about writing and thus reading through the senses, Jamaica Kincaid creates prose that inhabits them all.

A 5 star read for me!

It is a novel narrated in parts, each part focusing on a character(s) who were influential in her life, including the young man who never knew her until this day, the one who became her confidant, perhaps the first man she ever trusted, after all that had passed beforehand. Much of it is told as Mala slips into memories of herself as child, reliving it.

It is a novel narrated in parts, each part focusing on a character(s) who were influential in her life, including the young man who never knew her until this day, the one who became her confidant, perhaps the first man she ever trusted, after all that had passed beforehand. Much of it is told as Mala slips into memories of herself as child, reliving it. As Tyler gained her trust, Mala’s story is revealed to us through him and through the two visitors she received, who on her first day there, unable to see her, left a pot with a cutting of the fragrant night-blooming cereus plant, a gift that clearly delighted her, a symbol of fragrant, nurturing oblivion.

As Tyler gained her trust, Mala’s story is revealed to us through him and through the two visitors she received, who on her first day there, unable to see her, left a pot with a cutting of the fragrant night-blooming cereus plant, a gift that clearly delighted her, a symbol of fragrant, nurturing oblivion.

Marlon James novel A Brief History of Seven Killings was the winner of the

Marlon James novel A Brief History of Seven Killings was the winner of the  I can’t say I loved it, it was a tough read in places and definitely not the kind of book I would normally choose nor the kind of film/TV series I would watch, but it is an awe-inspiring creation and for that I agree, it is indeed an amazing oeuvre and warrants the 5 stars, though as far as favourite books go or works I’d recommend, I hesitate and would say its not an experience I would choose to repeat often.

I can’t say I loved it, it was a tough read in places and definitely not the kind of book I would normally choose nor the kind of film/TV series I would watch, but it is an awe-inspiring creation and for that I agree, it is indeed an amazing oeuvre and warrants the 5 stars, though as far as favourite books go or works I’d recommend, I hesitate and would say its not an experience I would choose to repeat often. I was left admiring the creation even if it wasn’t always a particularly enjoyable ride and as my comment made to another reader below shows, the beach was actually a great place to read it!

I was left admiring the creation even if it wasn’t always a particularly enjoyable ride and as my comment made to another reader below shows, the beach was actually a great place to read it!

Absolutely brilliant, astonishing, loved it, one of my Top Reads of 2016 for sure.

Absolutely brilliant, astonishing, loved it, one of my Top Reads of 2016 for sure.

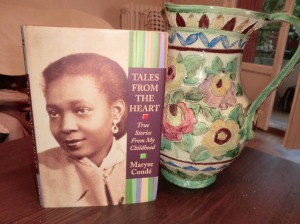

I first read Haitian author, Edwidge Danticat last summer, her novel Breath, Eyes, Memory (review linked below) about a young girl living with her Aunt in Haiti, while her mother lived in New York, a little like the life of the author herself, much of which is revealed in this non-fiction title, Brother, I’m Dying where we learn more about her life, though the primary focus is on her father Mira and in particular, her Uncle Joseph.

I first read Haitian author, Edwidge Danticat last summer, her novel Breath, Eyes, Memory (review linked below) about a young girl living with her Aunt in Haiti, while her mother lived in New York, a little like the life of the author herself, much of which is revealed in this non-fiction title, Brother, I’m Dying where we learn more about her life, though the primary focus is on her father Mira and in particular, her Uncle Joseph.