This novel is like nothing else I’ve ever read, it describes an inner world, an occupied mind, from that inside. It puts the reader in a position of imagining, perhaps even to a certain degree understanding, what it might be like to have your subconscious and conscious mind occupied by other entities, entities with a voice, with personality, that from time to time take over the body, affect behaviour, talk to you and through you.

This novel is like nothing else I’ve ever read, it describes an inner world, an occupied mind, from that inside. It puts the reader in a position of imagining, perhaps even to a certain degree understanding, what it might be like to have your subconscious and conscious mind occupied by other entities, entities with a voice, with personality, that from time to time take over the body, affect behaviour, talk to you and through you.

Reality is depicted from their perspective, giving full voice to the multiple entities, birthed (through traumas) at different times during the life of Ada (her name though her father told her just meant ‘precious’, in its truest form, meant, the egg of a python), who was born a girl (though doesn’t stay one) in Nigeria and educated in America, where much of the narrative takes place.

We become aware of their presence from the opening pages, before they are awakened within Ada, in a chapter that is utterly compelling as we come to realise who the ‘we‘ is that is narrating much of the story. And ‘we‘ is not the only non-human narrator.

These personalities inhabit a place (referred to in the text as the marble room) within the body/mind, they lie dormant until they are awakened, they keep each other company in that space, they co-habit this one body and constantly justify their existence and inclinations and sometimes act out on them, though they too seem capable of evolving, just as their human needs to and does. And just in case you think this is sounding like fantasy or science fiction, it’s not, this is a semi-autobiographical novel, much of it corresponds to the author’s experience and perceived reality of the world.

These multiple entities exist, they are not illusions or metaphors, they have names and characteristics that manifest into different behaviours through human ‘Ada’ who simultaneously suffers from them, is supported by them, at times is even dependent on them. They are one, but with many aspects that from the external perspective risk being judged as something labelled otherwise depending on the country/culture – such as personality disorder or schizophrenia due to our limited view in defining other states of being. When one entity is more present, Ada’s way of being in the world alternates between her human personality and that of the other presence, whether it’s we, Asughara, or Saint Vincent.

Ogbanje by Akwaeke Emezi

From the perspective of Nigerian ontology (philosophical study of the nature of being), Ada (as the author also self-identifies) may be perceived as ‘ogbanje‘, a child that usually doesn’t live long and is often reborn into the same family. It is believed that these children recognise the difficulty of living in this world and choose to leave it, only on arriving at the gates of heaven they’re denied entry, they’re judged as being lazy and indolent and are sent back to try again. When they are present in the world, they often have particular psychic abilities and/or an other-worldliness about them, they’re believed by some to be possessed, they don’t particularly enjoy the dense, limited human body and experience.

Ogbanje (noun): An embodied spirit passing as human, who transitions rapidly between birth and death, i.e. possessing the ability to ‘come and go’.

Only the child Ada is saved from a death that might have sent her back by her father, a modern Igbo man with medical training from the Soviet Union and years of living in London. He did not believe in anything superstitious that might have made him view the scene he rescued her from as anything other than death. In rescuing her, he prevents the entities from leaving.

He had no idea what he had done.

Akwaeke Emezi depicts these influences and describes being human as a temporary vessel for this other kind of presence which until Ada understands and accepts it, she will continue to suffer as if she is one and not all of them. The ability to make them so real to the reader, to create what feel like real characters from them, is astounding.

“All the madnesses, each and every blinding one, they can all be traced back to the gates. Those carved monstrosities, those clay and chalk portals, existing everywhere and nowhere and all at once. They open, things are born, they close. The opening is easy, a pushing out, an expansion, an inhalation: the dust of divinity released into the world. It has to be a temporary channel, though, a thing that is sealed afterward, because the gates stink of knowledge, they cannot be left swinging wide like a slack mouth, leaking mindlessly. That would contaminate the human world – bodies are not meant to remember things from the other side. There are rules. But these are gods and they move like heated water, so the rules are softened and stretched. The gods do not care. It is not them after all, that will pay the cost.”

At one point Ada seeks out a therapist and at first her entities don’t notice, they are not always present, but they’d told her to keep them inside her head, in the marble room, so no one could see them.

So when she started looking up her “symptoms”, it felt like a betrayal – like she thought we were abnormal. How can we be, when we were her and she was us? I watched her try to tell people about us and I smiled when they told her it was normal to have different parts of yourself.

The entities try to fulfill their destiny (to return to their spirit siblings) and thus sabotage Ada’s attempts to live a human life with minimal suffering. It’s a constant challenge to navigate life, until they learn to live in harmony and she understands her purpose after an encounter with a historian, who tells her what she needs to accept.

“The name that was given to you has many connotations, you hear?” He wore glasses and spoke in a rush of words. “The python’s egg means a precious child. A child of the gods, or the deity themself. The experiences you’ve had suggest that there is a spiritual connection, which you need to go and learn about. Your journey will not be complete until you do that.” He leaned back and folded his arms. “There is nothing more anybody can tell you. It’s important for you to understand your place on this earth.”

Truly an astounding, transparent work that takes an understanding of the being part of human into another dimension. The way it seamlessly moves from the material to the immaterial, combining human and spiritual aspects of selves, on a journey to assemble some way of living with them both, in a world where the majority live within and perceive only one aspect and dimension, a world indeed, where it can be dangerous to articulate this alternate reality.

I thought it was brilliant, definitely a 5 star read for me and truly deserving of being on the Women’s Prize for Fiction longlist.

A debut novel said to have an autobiographical slant, this is how Akwaeke Emezi brilliantly articulates what the writing of it meant to them in an interview with Ms. magazine:

I wrote Freshwater as an analysis of sorts—the ogbanje figuring out what it is, ascribing legibility to itself. We look at our worlds through a limited range of lenses, and making this book meant choosing a different center to tell the story from, a different lens to look through.

Once that shift was made, it came with such clarity—the world finally making sense. Being a strange thing in a human world and not knowing what you are is immensely difficult, and I think Freshwater walks us pretty intimately through what living in that space feels like.

Highly Recommended.

Further Reading

New Yorker: A Startling Debut Novel Explores the Freedom of Being Multiple by Katy Waldman

Interview: The Ms. Q&A: Akwaeke Emezi on Freshwater and Finding Home by Taliah Mancini

N.B. Thank you to publisher Grove Atlantic for providing a review copy.

Interested in the inspiration for writing a novel, this one intrigued me; Bernice McFadden visited Ghana in 2007 and while she was there met two women who told her about a rehabilitation centre and a tradition referred to as trokosi, which they explained and suggested she write a book about, an idea she initially laughed at, but after researching the practice, a story began to emerge that she eventually pursued.

Interested in the inspiration for writing a novel, this one intrigued me; Bernice McFadden visited Ghana in 2007 and while she was there met two women who told her about a rehabilitation centre and a tradition referred to as trokosi, which they explained and suggested she write a book about, an idea she initially laughed at, but after researching the practice, a story began to emerge that she eventually pursued.

Interested in the title, I looked up ‘Praise Song’ and learned it is one of the most widely used poetic forms in African literature; described as ‘a series of laudatory epithets applied to gods, men, animals, plants, and towns that capture the essence of the object being praised’.

Interested in the title, I looked up ‘Praise Song’ and learned it is one of the most widely used poetic forms in African literature; described as ‘a series of laudatory epithets applied to gods, men, animals, plants, and towns that capture the essence of the object being praised’. Bernice McFadden is the author of nine critically acclaimed novels including Sugar, Loving Donovan, Nowhere is a Place, The Warmest December, Gathering of Waters and The Book of Harlan (winner of American Book Award and NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work, Fiction). A four-time Hurston/Wright Legacy Award finalist, I’ll definitely be reading more of her work.

Bernice McFadden is the author of nine critically acclaimed novels including Sugar, Loving Donovan, Nowhere is a Place, The Warmest December, Gathering of Waters and The Book of Harlan (winner of American Book Award and NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work, Fiction). A four-time Hurston/Wright Legacy Award finalist, I’ll definitely be reading more of her work.

In an interview, Novuyo Rosa Tshuma when asked about setting her novel amidst the backdrop of this massacre, said:

In an interview, Novuyo Rosa Tshuma when asked about setting her novel amidst the backdrop of this massacre, said: It’s an accomplished novel that confronts harsh truths and pursues questions about the reinvention of a nation and the individual. A gifted storyteller who has been able to weave the essence of those personal narratives into richly formed characters that goes some way towards acknowledging a history no-one will talk about. Bereft of redemption, a feeling that pervades the narrative and one that seems to hold many in its grip today worldwide.

It’s an accomplished novel that confronts harsh truths and pursues questions about the reinvention of a nation and the individual. A gifted storyteller who has been able to weave the essence of those personal narratives into richly formed characters that goes some way towards acknowledging a history no-one will talk about. Bereft of redemption, a feeling that pervades the narrative and one that seems to hold many in its grip today worldwide. I came across this promising book on a Goodreads group called

I came across this promising book on a Goodreads group called  It’s a coming of age story of Tambu, a teenage girl, who in the beginning lives in a small village with her parents and siblings and their days are hard, especially the women, who work in the fields all day, do the laundry at the river, transport water to and fro and cook in a kitchen that lacks modern conveniences and requires skill and tenacity to manage. Despite the hard work Tambu loves her village and even the work and chores equally provide moments of pleasure and companionship.

It’s a coming of age story of Tambu, a teenage girl, who in the beginning lives in a small village with her parents and siblings and their days are hard, especially the women, who work in the fields all day, do the laundry at the river, transport water to and fro and cook in a kitchen that lacks modern conveniences and requires skill and tenacity to manage. Despite the hard work Tambu loves her village and even the work and chores equally provide moments of pleasure and companionship. The subtle way her character transitions to greater awareness is adeptly portrayed, her feelings of ambition and regret as she realises it may be impossible to achieve all that she aspires to without losing something of what she had. She observes her cousin rebel and then accept that middle ground, fall victim to it, unable to go back to who she was, becoming alienated from her own, entering into self-destructive territory.

The subtle way her character transitions to greater awareness is adeptly portrayed, her feelings of ambition and regret as she realises it may be impossible to achieve all that she aspires to without losing something of what she had. She observes her cousin rebel and then accept that middle ground, fall victim to it, unable to go back to who she was, becoming alienated from her own, entering into self-destructive territory.

Again, my outstanding read of the year came early in the year, one of the most underrated novels of the year, that should have been given more attention, in my opinion.

Again, my outstanding read of the year came early in the year, one of the most underrated novels of the year, that should have been given more attention, in my opinion.

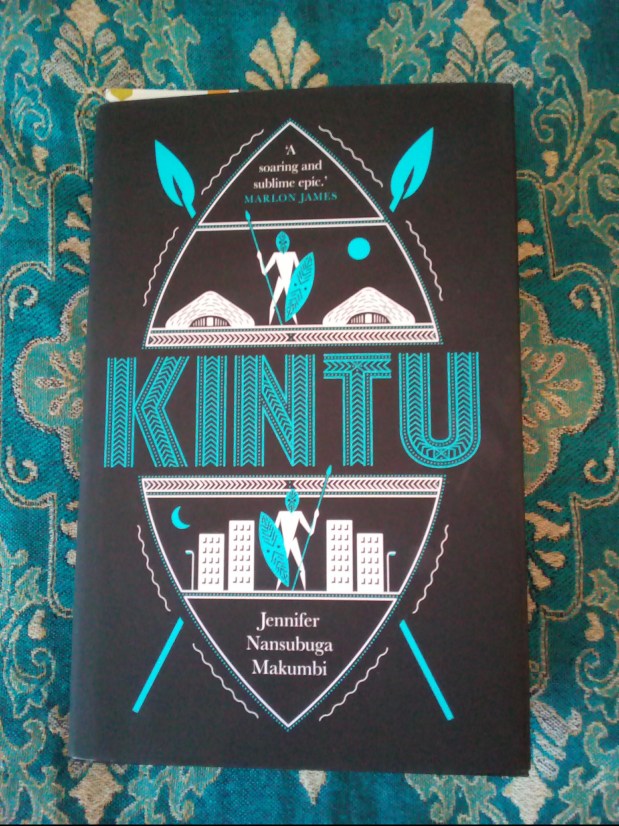

This is what appealed to me immediately about the prospect of reading Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu. It promises to do the same thing, to take the reader from where we are at today in a culture and link it back to the past, from modern day Uganda to the era of when the region was ruled as a kingdom. And it succeeds brilliantly, in a way rarely seen in literature in the UK/US published today.

This is what appealed to me immediately about the prospect of reading Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu. It promises to do the same thing, to take the reader from where we are at today in a culture and link it back to the past, from modern day Uganda to the era of when the region was ruled as a kingdom. And it succeeds brilliantly, in a way rarely seen in literature in the UK/US published today.

Some are haunted by ghosts of the past, thinking themselves not of sound mind, particularly when aspects of their childhood have been hidden from them, some have prophetic dreams, some have had a foreign university education and try to sever their connections to the old ways, though continue to be haunted by omens and symbols, making it difficult to ignore what they feel within themselves, that their mind wishes to reject. Some turn to God and the Awakened, looking for salvation in newly acquired religions.

Some are haunted by ghosts of the past, thinking themselves not of sound mind, particularly when aspects of their childhood have been hidden from them, some have prophetic dreams, some have had a foreign university education and try to sever their connections to the old ways, though continue to be haunted by omens and symbols, making it difficult to ignore what they feel within themselves, that their mind wishes to reject. Some turn to God and the Awakened, looking for salvation in newly acquired religions.

This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness.

This short, articulate novella is a conversation, in the form of a lengthy letter from a widow to her best friend, whom she hasn’t seen for some years, but who is arriving tomorrow. It is set in Senegal, was originally written and published in French in 1980 and in English in 1981, the year in which the author died tragically of a long illness. It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s

It is a lament, a paradox of feelings, a resentment of tradition, a wonder at those like her more liberated and courageous friend, who in protest at her own unfair treatment (a disapproving mother-in-law interferes – reminding me of Ayòbámi Adébáyò’s  Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents.

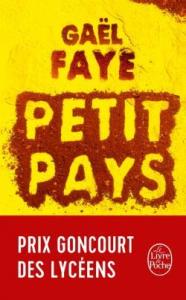

Mariama Bâ (April 17, 1929 – August 17, 1981) was a Senegalese author and feminist, who wrote in French. Born in Dakar to an educated and well-off family, her father was Minister of Health, her grandfather a translator in the occupying French regime. After the premature death of her mother, she was largely raised in the traditional manner by her maternal grandparents. Once I got into the rhythm of this, which is to say, reading in French, and getting past the need to look up too many new words, I couldn’t put this down, by the time I found my reading rhythm, the lives of Gabriel (Gaby) and his sister Ana, his parents, his friends had their claws in me and I had to know what was going to happen next.

Once I got into the rhythm of this, which is to say, reading in French, and getting past the need to look up too many new words, I couldn’t put this down, by the time I found my reading rhythm, the lives of Gabriel (Gaby) and his sister Ana, his parents, his friends had their claws in me and I had to know what was going to happen next. His father is French, his mother Tutsi from Rwanda, they live in the small country bordering Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo, called Burundi. It boasts the second deepest lake in the world, Lake Tanganyika, which occupies a large portion of the country’s border and is part of the African Great Lakes region.

His father is French, his mother Tutsi from Rwanda, they live in the small country bordering Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo, called Burundi. It boasts the second deepest lake in the world, Lake Tanganyika, which occupies a large portion of the country’s border and is part of the African Great Lakes region.

The ending is not really an ending, it could be said there is more than one ending and perhaps there may even be another book. I found it incredibly moving and was amazed to be so moved in a language that is not my own. An incredible feat of writing, a wonderful talent.

The ending is not really an ending, it could be said there is more than one ending and perhaps there may even be another book. I found it incredibly moving and was amazed to be so moved in a language that is not my own. An incredible feat of writing, a wonderful talent. I’m guessing that Ayobami Adebayo uses it as the title to her novel, because it relates to the twin desires of the main characters in the book, Yejide in her yearning to become pregnant and to keep a child, to be the mother she was denied, having been raised by less than kind stepmothers after her mother died in childbirth; and her husband Akin, in his desire to try to keep his wife happy and with him, despite succumbing to the pressures of the stepmothers and his own family, he being the first-born son of the first wife, to produce a son and heir.

I’m guessing that Ayobami Adebayo uses it as the title to her novel, because it relates to the twin desires of the main characters in the book, Yejide in her yearning to become pregnant and to keep a child, to be the mother she was denied, having been raised by less than kind stepmothers after her mother died in childbirth; and her husband Akin, in his desire to try to keep his wife happy and with him, despite succumbing to the pressures of the stepmothers and his own family, he being the first-born son of the first wife, to produce a son and heir. The narrative voice moves from first person accounts of both Yejide and Akin, ensuring the reader gains twin perspectives on what is happening (and making us a little unsure of reality) and the more intimate second person narrative in the present day, as each character addresses the other with that more personal “you” voice, they are not in each other’s presence, but they carry on a conversation in their minds, addressing each other, asking questions that will not be answered, wondering what the coming together after all these years will reveal.

The narrative voice moves from first person accounts of both Yejide and Akin, ensuring the reader gains twin perspectives on what is happening (and making us a little unsure of reality) and the more intimate second person narrative in the present day, as each character addresses the other with that more personal “you” voice, they are not in each other’s presence, but they carry on a conversation in their minds, addressing each other, asking questions that will not be answered, wondering what the coming together after all these years will reveal.