I’ve been aware of this novel and reading about it for a long time, watching it come through and finally win the 2017 Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction and I love that this will ensure it is widely read, because perhaps the greatest value to this story is to provoke readers to discuss it, not so much the actual story, but the theoretical constructs behind it and how it exposes the way we think and accept things as they are today and yet when twisted on their head as Naomi Alderman has done in The Power, we become ever more acutely aware of the gravity and depravity of that thinking.

I’ve been aware of this novel and reading about it for a long time, watching it come through and finally win the 2017 Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction and I love that this will ensure it is widely read, because perhaps the greatest value to this story is to provoke readers to discuss it, not so much the actual story, but the theoretical constructs behind it and how it exposes the way we think and accept things as they are today and yet when twisted on their head as Naomi Alderman has done in The Power, we become ever more acutely aware of the gravity and depravity of that thinking.

The Power is the story of a manuscript sent from one friend to another, thus it’s bookended by their correspondence, before and after we, along with Naomi (the recipient of the manuscript) read Neil’s historical novel ‘The Power’.

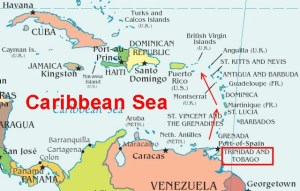

The story follows a period in (and looking back on) the lives of four characters, the first part is entitled Ten Years to Go, finishing with the final part Here It Comes. The characters come from different parts of the world; Roxy, the daughter of a British crime boss, traumatised by the accidental witnessing of her mother’s murder, who finds the safest place to be is among those whom she most fears; Allie, an abused foster child who escapes and changes her identity, guided by an inner voice and destined to lead, who will become the religious leader Mother Eve; Tunde, a Nigerian youth who discovers his calling as the witness and recorder of events as they unfold, leaves his country and follows the rise of women as they assume The Power in one of the most extreme locations, where leadership is more akin to dictatorship and the population becomes more and more extreme in response to the fear and punishments generated by an increasingly corrupt leadership; and finally Margot, an ambitious American politician who is well placed for the transition, whose troubled daughter Jocelyn becomes the recipient of some of her initiatives.

Rather than finding ourselves in the midst of a society already run by women, the story takes place as women are beginning to assume control and the reason they can do so is because of their unique ability to inflict pain, in a way men can not.

Through the experiences of these characters, we witness what happens as power shifts, their narratives coming together in the newly declared kingdom in Moldova, where the President has been deposed by his wife Tatiana.

“And there she declares a new kingdom, uniting the coastal lands between the old forests, and the great inlets and thus, in effect, declaring war on four separate countries, including the Big Bear herself. She calls the new country Bessapara, after the ancient people who lived there and interpreted the sacred sayings of the priestesses on the mountaintops.

It’s a book that keeps the reader guessing, wondering what the impact of this shift in power will be, will we see something different from what we know, or will women turn out to be as similarly corrupted by power as men?

As the path the author has chosen plays out on the page, the reader encounters thought provoking reactions to how they perceive what happens when roles are reversed, for as Naomi Alderman shared when her novel made the shortlist of the Bailey’s Prize:

“I didn’t start from the idea of making a matriarchal society. But the idea did come from a particular moment in my life. I was going through a really horrible breakup, one of those ones where you wake up every morning, have a cry and then get on with your day. And in the middle of all this emotional turmoil, I got onto the tube and saw a poster advertising a movie with a photograph of a beautiful woman crying, beautifully. And in that moment it felt like the whole of the society I live in saying to me “oh yes, we like it when you cry, we think it’s sexy”. And something just snapped in me and all I could think was: what would it take for me to be able to get onto this tube train and see a sexy photo of a *man* crying? What’s the smallest thing I could change? And this novel is the answer to that question, or at least an attempt to think it through for myself. …I just had this idea about women developing a strange new power.”

Overall, I liked the book for its provocation and the conversation it generates, but the story itself and the inner landscapes it explores, the places it takes us, aren’t states of mind or dwellings I prefer to inhabit in literature and because equally in addition to there being a perceived rise in rhetoric against equality for women today, there is simultaneously, depending on what information channels and voices we expose ourselves to, a rise in empathic consciousness – so yes, we are in a time of critical transition and equally many are rejecting the conditioning of the past, embracing a more compassionate, altruistic way of being.

The title ‘Frantumaglia‘, a fabulous word left to her by her mother, in her Neapolitan dialect, a word she used to describe how she felt when racked by contradictory sensations that were tearing her apart.

The title ‘Frantumaglia‘, a fabulous word left to her by her mother, in her Neapolitan dialect, a word she used to describe how she felt when racked by contradictory sensations that were tearing her apart. The first half chiefly concerns communication around Troubling Love and

The first half chiefly concerns communication around Troubling Love and

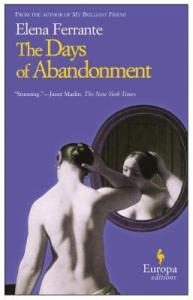

In an interview, Stefania Scateni from the publication l’Unità, refers to Olga, the protagonist of The Days of Abandonment as destroyed by one love, seeking another with her neighbour. He asks what Ferrante thinks of love.

In an interview, Stefania Scateni from the publication l’Unità, refers to Olga, the protagonist of The Days of Abandonment as destroyed by one love, seeking another with her neighbour. He asks what Ferrante thinks of love. The correspondence with the Director of Troubling Love (L’amore molesto), Mario Martone is illuminating, to read of Ferrante’s humble hesitancy in contributing to a form she confessed to know nothing about, followed by her exemplary input to the process and finally the unsent letter, many months later when she finally saw the film and was so affected by what he had created. It makes me want to read her debut novel and watch the original cult film now.

The correspondence with the Director of Troubling Love (L’amore molesto), Mario Martone is illuminating, to read of Ferrante’s humble hesitancy in contributing to a form she confessed to know nothing about, followed by her exemplary input to the process and finally the unsent letter, many months later when she finally saw the film and was so affected by what he had created. It makes me want to read her debut novel and watch the original cult film now. The shortlisted books are as follows:

The shortlisted books are as follows:

The Dark Circle, Linda Grant

The Dark Circle, Linda Grant

Stay With Me, Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀̀

Stay With Me, Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀̀ The Sport of Kings, C.E. Morgan

The Sport of Kings, C.E. Morgan First Love, Gwendoline Riley

First Love, Gwendoline Riley I’m guessing that Ayobami Adebayo uses it as the title to her novel, because it relates to the twin desires of the main characters in the book, Yejide in her yearning to become pregnant and to keep a child, to be the mother she was denied, having been raised by less than kind stepmothers after her mother died in childbirth; and her husband Akin, in his desire to try to keep his wife happy and with him, despite succumbing to the pressures of the stepmothers and his own family, he being the first-born son of the first wife, to produce a son and heir.

I’m guessing that Ayobami Adebayo uses it as the title to her novel, because it relates to the twin desires of the main characters in the book, Yejide in her yearning to become pregnant and to keep a child, to be the mother she was denied, having been raised by less than kind stepmothers after her mother died in childbirth; and her husband Akin, in his desire to try to keep his wife happy and with him, despite succumbing to the pressures of the stepmothers and his own family, he being the first-born son of the first wife, to produce a son and heir. The narrative voice moves from first person accounts of both Yejide and Akin, ensuring the reader gains twin perspectives on what is happening (and making us a little unsure of reality) and the more intimate second person narrative in the present day, as each character addresses the other with that more personal “you” voice, they are not in each other’s presence, but they carry on a conversation in their minds, addressing each other, asking questions that will not be answered, wondering what the coming together after all these years will reveal.

The narrative voice moves from first person accounts of both Yejide and Akin, ensuring the reader gains twin perspectives on what is happening (and making us a little unsure of reality) and the more intimate second person narrative in the present day, as each character addresses the other with that more personal “you” voice, they are not in each other’s presence, but they carry on a conversation in their minds, addressing each other, asking questions that will not be answered, wondering what the coming together after all these years will reveal.

It is a novel narrated in parts, each part focusing on a character(s) who were influential in her life, including the young man who never knew her until this day, the one who became her confidant, perhaps the first man she ever trusted, after all that had passed beforehand. Much of it is told as Mala slips into memories of herself as child, reliving it.

It is a novel narrated in parts, each part focusing on a character(s) who were influential in her life, including the young man who never knew her until this day, the one who became her confidant, perhaps the first man she ever trusted, after all that had passed beforehand. Much of it is told as Mala slips into memories of herself as child, reliving it. As Tyler gained her trust, Mala’s story is revealed to us through him and through the two visitors she received, who on her first day there, unable to see her, left a pot with a cutting of the fragrant night-blooming cereus plant, a gift that clearly delighted her, a symbol of fragrant, nurturing oblivion.

As Tyler gained her trust, Mala’s story is revealed to us through him and through the two visitors she received, who on her first day there, unable to see her, left a pot with a cutting of the fragrant night-blooming cereus plant, a gift that clearly delighted her, a symbol of fragrant, nurturing oblivion.

From her early days, Firdaus was a child who was noticed, though rarely looked out for, instances of cruelty and neglect made up the patchwork of her childhood. “Rescued” by an Uncle who’d already crossed filial boundaries, her one respite was to have been sent by him to school, his new wife further insisting she live there, perhaps the only paradisiacal period of her life, the one time she was left alone to flourish, to evolve, gaining her secondary school certificate, her sole prized possession.

From her early days, Firdaus was a child who was noticed, though rarely looked out for, instances of cruelty and neglect made up the patchwork of her childhood. “Rescued” by an Uncle who’d already crossed filial boundaries, her one respite was to have been sent by him to school, his new wife further insisting she live there, perhaps the only paradisiacal period of her life, the one time she was left alone to flourish, to evolve, gaining her secondary school certificate, her sole prized possession.

Buddha in the Attic is a unique novella told in the first person plural “we”, narrating the story of a group of young women brought from Japan to San Francisco as “picture brides” nearly a century ago.

Buddha in the Attic is a unique novella told in the first person plural “we”, narrating the story of a group of young women brought from Japan to San Francisco as “picture brides” nearly a century ago. And as if it couldn’t get any worse, war happens, and they discover they are the enemy, they are regarded suspiciously and in time sent away.

And as if it couldn’t get any worse, war happens, and they discover they are the enemy, they are regarded suspiciously and in time sent away. It reminded me, not in style, but in subject of Jamie Ford’s

It reminded me, not in style, but in subject of Jamie Ford’s

Which all leads me on to say it was with quiet anticipation to learn that Dawn Tripp had the courage, respect and admiration for O’Keeffe to decide to venture into creating a work of fiction, that attempts to channel the voice of Georgia O’Keeffe. What might she have really been thinking if it was her voice relating the story of this life and not someone from the outside.

Which all leads me on to say it was with quiet anticipation to learn that Dawn Tripp had the courage, respect and admiration for O’Keeffe to decide to venture into creating a work of fiction, that attempts to channel the voice of Georgia O’Keeffe. What might she have really been thinking if it was her voice relating the story of this life and not someone from the outside. When the novel was almost complete, the correspondence of O’Keeffe and Stieglitz was published, having been sealed for twenty-five years after her death.

When the novel was almost complete, the correspondence of O’Keeffe and Stieglitz was published, having been sealed for twenty-five years after her death.

“Pink Tulip”, 1926, Georgia O’Keeffe, oil on canvas, 36” x 30”

“Pink Tulip”, 1926, Georgia O’Keeffe, oil on canvas, 36” x 30”

The cover is an apt metaphor of the book, where water plays a significant role in multiple turning points in the novel and the image of a woman half-submerged, reminds me of that ability a person has of appearing to cope and be present on and above the surface, when beneath that calm exterior, below in the murky depths, unseen elements apply pressure, disturbing the tranquil image.

The cover is an apt metaphor of the book, where water plays a significant role in multiple turning points in the novel and the image of a woman half-submerged, reminds me of that ability a person has of appearing to cope and be present on and above the surface, when beneath that calm exterior, below in the murky depths, unseen elements apply pressure, disturbing the tranquil image. We arrive in a hill city of Kandy in Sri Lanka where she recounts her solitary, yet idyllic childhood, among the scent of tropical gardens, a big old house, ‘sweeping emerald lawns leading down to the rushing river‘ overlooked by monsoon clouds.

We arrive in a hill city of Kandy in Sri Lanka where she recounts her solitary, yet idyllic childhood, among the scent of tropical gardens, a big old house, ‘sweeping emerald lawns leading down to the rushing river‘ overlooked by monsoon clouds.