In 2017 I anticipated that I wouldn’t read as much as I had read in previous years, due to giving my reading time over to some personal studies and the reading that would accompany them and to the social visits I had from many of the men in my family, brother, Uncle, Fathers. As a result, less of my writing appeared here in Word by Word and more of it found its way in the old-fashioned long form between the pages of journals that I keep.

However, I did still manage to read 48 books from 21 countries (10 in translation) including Sri Lanka, Trinidad, Turkey, Ireland, Nigeria, Ghana, Palestine, Italy, Canada, Scotland, Pakistan, France, South Africa, Guadeloupe, Greece, Spain, Mauritius, Australia and of course the UK and the US.

Outstanding Read of 2017

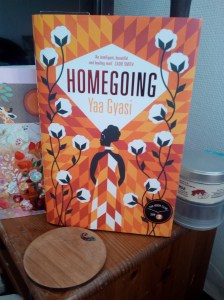

The one stand out novel for me came very early in the year, in February and I knew as soon as I finished it, that it was likely to be my outstanding novel of 2017.

The one stand out novel for me came very early in the year, in February and I knew as soon as I finished it, that it was likely to be my outstanding novel of 2017.

This novel came out with a lot of fanfare and so I was a little dubious to begin with, novels that arrive with great expectations have a tendency to disappoint avid literary readers, so I read with intrigue what other reviewers had to say. Some loved it, others saw it as a collection of stories, and then my very dear Aunt, who totally knows what kind of books I love sent it to me for my birthday. Of course I dove right in.

Here is what I had to say in my review:

“I love, love, loved this novel and I am in awe of its structure and storytelling, the authenticity of the stories, the three-dimensional characters, the inheritance and reinvention of trauma, and the rounding of all those stories into the healing return. I never saw that ending coming and the build up of sadness from the stories of the last few characters made the last story all the more moving, I couldn’t stop the tears rolling down my face.”

Yaa Gyasi was born in Ghana, but lived most of her life in the US. After revisiting Ghana, she began writing her novel by asking herself what it meant to be black in America today and through the lives and descendants of two sisters, her narrative will arrive eventually in the modern day. Here’s what she was trying to do and in my opinion totally succeeds. Read my review here.

I began Homegoing in 2009 after a trip to Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle [where slaves were incarcerated]. The tour guide told us that British soldiers who lived and worked in the castle often married local women – something I didn’t know. I wanted to juxtapose two women – a soldier’s wife with a slave. I thought the novel would be traditionally structured, set in the present, with flashbacks to the 18th century. But the longer I worked, the more interested I became in being able to watch time as it moved, watch slavery and colonialism and their effects – I wanted to see the through-line.

Top Reads 2017

Here in no particular order are a few books that have stayed with me long after I read them and the year has passed.

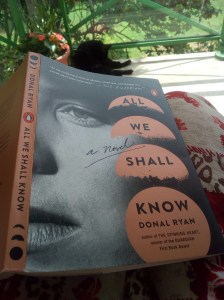

All We Shall Know by Donal Ryan is a slim novella, the third book by this young Irish writer and his best in my opinion.

All We Shall Know by Donal Ryan is a slim novella, the third book by this young Irish writer and his best in my opinion.

The story is told in a way that pulls you inside the book and makes you feel it happening. Incredibly the author writes from the first person perspective of Melody, a 33-year-old woman who discovers she is pregnant to a young Traveller, a turning point that disrupts the confined world she has created and had been living in.

He has such penetrative powers of observation, that create a sense of foreboding and intrigue, it’s a book you’ll likely read in one sitting and then wonder in awe, how he did that. Just brilliant.

You can read my full review here.

Salt Creek by Lucy Treloar was published by Gallic Books new imprint Aardvark Bureau, I’ve loved all the books they’ve brought out under this imprint and Salt Creek might just be the best so far. It’s an historical novel, inspired by the events of the authors family, who immigrated to Australia from Britain, portraying one family trying to find success in farming in a harsh, unforgiving environment of South Australia.

Salt Creek by Lucy Treloar was published by Gallic Books new imprint Aardvark Bureau, I’ve loved all the books they’ve brought out under this imprint and Salt Creek might just be the best so far. It’s an historical novel, inspired by the events of the authors family, who immigrated to Australia from Britain, portraying one family trying to find success in farming in a harsh, unforgiving environment of South Australia.

This too is a book that gets under your skin, especially as a woman reading about the lives of other women and children (particularly daughters) who are at the mercy of the dreams and aspirations of men, men who have little empathy for how disruptive and out of the comfort zone, this life might be for a woman, and ironically, on the contrary, how quickly young children adapt, how easy it is for them to integrate and thus cross societal taboos when it comes to mixing with indigenous populations. It’s a novel richly populated with colonial issues of the time, that make you wish at times, that it could have a fantasy element, where it all might end differently.

Read my full review of Salt Creek here.

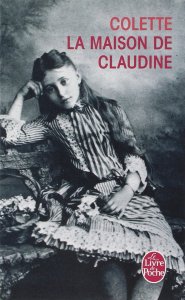

The Complete Claudine by Colette (translated by Antonia White) was my One Summer Chunkster for 2017, a French classic, relatively little known outside France among general readers, but an author who should be more widely read, especially by young adult readers, as it charts the young Claudine’s journey through her last year in school, then her adventures in Paris with her father, through marriage and into maturity.

The Complete Claudine by Colette (translated by Antonia White) was my One Summer Chunkster for 2017, a French classic, relatively little known outside France among general readers, but an author who should be more widely read, especially by young adult readers, as it charts the young Claudine’s journey through her last year in school, then her adventures in Paris with her father, through marriage and into maturity.

The book includes an excellent introduction by Judith Thurman, which I devoted a full post to, as she was such a fascinating woman, so far ahead of the era in which she lived, being such a free spirit, determined to experience love, to live her artistic desires and be financially independent, wild and adorable!

Below are the links to the introductory piece and the four books that are contained in this one volume.

Sidonie Gabrielle Colette by Leopold Reutlinger

A brilliant choice for my one fat summer book of the year.

The Complete Claudine – An Introduction

Claudine at School

Claudine in Paris

Claudine Married

Claudine and Annie

Two Old Women by Velma Wallis is a quirky fable-like book I read about and was intrigued by, recommended by a fellow reader. It is an Alaskan legend of betrayal, courage and survival, one which features, as the title suggests, two old women.

Two Old Women by Velma Wallis is a quirky fable-like book I read about and was intrigued by, recommended by a fellow reader. It is an Alaskan legend of betrayal, courage and survival, one which features, as the title suggests, two old women.

This is one of those stories, like Najaf Mazari’s excellent collection The Honey Thief, handed down in the oral tradition from generation to generation and now finally, thankfully, someone has captured it in print, so it can endure and be discovered by an even wider audience than originally intended.

I loved it because it teaches us the value of paying attention to our (women) elders, who possess much wisdom, something that if ignored wastes away and can even be forgotten by those who possess it. Let not our elders sit too quietly, lest they believe they have creaky bones and limp minds! Read my full review here.

My Story by Jo Malone is one of the six memoirs I read in 2017 and the one that was the most intriguing and personal to me, not because I’m a fan of her perfumes, but because I too have a love of the aromas of plants, flowers, resins, herbs and like to create remedies from essential oils and mix them with other plant oils to use therapeutically.

My Story by Jo Malone is one of the six memoirs I read in 2017 and the one that was the most intriguing and personal to me, not because I’m a fan of her perfumes, but because I too have a love of the aromas of plants, flowers, resins, herbs and like to create remedies from essential oils and mix them with other plant oils to use therapeutically.

Knowing Jo Malone to be a high-end luxury brand, I had little idea that she came from such fascinating and humble beginnings and was a woman of such incredible perseverance. As I say below, I loved it!

“I absolutely loved this book, from it’s at times heartbreaking accounts of struggle in childhood, to the discovery of her passion, the development of her creativity and the strong work ethic that carried her forward, to finding the perfect mate and the journey they would go on together.”

Read my full review here.

Worthy Mentions

I could go on, but rather I will just say that I also really enjoyed the excellent debut novel Stay With Me by Ayobami Adebayo, Swimming Lessons by Claire Fuller was an accomplished evocative novel, Nayomi Munaweera’s Island of a Thousand Mirrors was as exquisite, heart-breaking and lyrical as I expected after her brilliant What Lies Between Us I’d read in 2016.

The Woman Next Door by Yewande Omotoso and The Story of the Cannibal Woman by Maryse Condé were a brilliant pair to read together, both placing a black Caribbean woman in South Africa while observing her relations with others around her, in a post-apartheid era. And personally I thought Zadie Smith’s depiction of female friendship in Swing Time easily rivalled Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, with her poignant insights and ever-present mastery of that sense of place and community, particularly in London. And though it didn’t reach the heights of Homegoing for me, Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing also left an equally strong impression:

“how living through Chairman Mao’s and the subsequent communist regime imprinted its effect on people’s behaviours forcing them to change, leaving its trace in their DNA which was passed on to subsequent generations, who despite living far from where those events took place, continue to live with a feeling they can’t explain, but which affects the way they live, or half-live, as something crucial to living a fulfilled life is missing. “

So did any of these books make your top reads for 2017? If not, what was your one Outstanding Read of the Year?

Happy Reading!

Having just read and loved Edna O’Brien’s trilogy

Having just read and loved Edna O’Brien’s trilogy

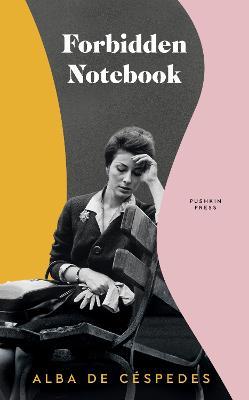

Valeria Cossati is a 42 year old Italian working wife, married with two children; one Sunday she is drawn to want to purchase a notebook in a local grocery store, a shop that is only permitted to be open on a Sunday, to sell tobacco. This purchase is her first act of transgression, the shopkeeper will allow it, but insists she hide the notebook in her coat.

Valeria Cossati is a 42 year old Italian working wife, married with two children; one Sunday she is drawn to want to purchase a notebook in a local grocery store, a shop that is only permitted to be open on a Sunday, to sell tobacco. This purchase is her first act of transgression, the shopkeeper will allow it, but insists she hide the notebook in her coat.

Alba de Céspedes (1911-1997) was a bestselling Italian-Cuban novelist, poet and screenwriter. The granddaughter of the first President of Cuba, who helped lead Cuba’s fight for independence, she was the daughter of a Cuban diplomat and his Italian wife, raised in Rome, Italy. She kept alive her family’s political commitment, often running afoul of Italy’s Fascist regime.

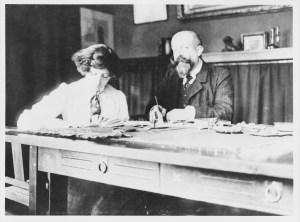

Alba de Céspedes (1911-1997) was a bestselling Italian-Cuban novelist, poet and screenwriter. The granddaughter of the first President of Cuba, who helped lead Cuba’s fight for independence, she was the daughter of a Cuban diplomat and his Italian wife, raised in Rome, Italy. She kept alive her family’s political commitment, often running afoul of Italy’s Fascist regime. The first ‘Letter to my nephew on the one hundredth anniversary of the emancipation’ entitled My Dungeon Shook originally appeared in the Progressive Madison, Wisconsin – a magazine known for its strong pacifism, championing grassroots progressive politics, civil liberties, human rights, economic justice, a healthy environment, and a reinvigorated democracy, is a letter to his 15 year old nephew James (who appears in a photo with his author Uncle on the cover of the book I read).

The first ‘Letter to my nephew on the one hundredth anniversary of the emancipation’ entitled My Dungeon Shook originally appeared in the Progressive Madison, Wisconsin – a magazine known for its strong pacifism, championing grassroots progressive politics, civil liberties, human rights, economic justice, a healthy environment, and a reinvigorated democracy, is a letter to his 15 year old nephew James (who appears in a photo with his author Uncle on the cover of the book I read).

I read Hadji Murad because it was referenced in the last pages of Leila Aboulela’s excellent

I read Hadji Murad because it was referenced in the last pages of Leila Aboulela’s excellent

All We Shall Know by Donal Ryan is a slim novella, the third book by this young Irish writer and his best in my opinion.

All We Shall Know by Donal Ryan is a slim novella, the third book by this young Irish writer and his best in my opinion. Salt Creek by Lucy Treloar was published by Gallic Books new imprint Aardvark Bureau, I’ve loved all the books they’ve brought out under this imprint and Salt Creek might just be the best so far. It’s an historical novel, inspired by the events of the authors family, who immigrated to Australia from Britain, portraying one family trying to find success in farming in a harsh, unforgiving environment of South Australia.

Salt Creek by Lucy Treloar was published by Gallic Books new imprint Aardvark Bureau, I’ve loved all the books they’ve brought out under this imprint and Salt Creek might just be the best so far. It’s an historical novel, inspired by the events of the authors family, who immigrated to Australia from Britain, portraying one family trying to find success in farming in a harsh, unforgiving environment of South Australia. The Complete Claudine by Colette (translated by Antonia White) was my One Summer Chunkster for 2017, a French classic, relatively little known outside France among general readers, but an author who should be more widely read, especially by young adult readers, as it charts the young Claudine’s journey through her last year in school, then her adventures in Paris with her father, through marriage and into maturity.

The Complete Claudine by Colette (translated by Antonia White) was my One Summer Chunkster for 2017, a French classic, relatively little known outside France among general readers, but an author who should be more widely read, especially by young adult readers, as it charts the young Claudine’s journey through her last year in school, then her adventures in Paris with her father, through marriage and into maturity.

Two Old Women by Velma Wallis is a quirky fable-like book I read about and was intrigued by, recommended by a fellow reader. It is an Alaskan legend of betrayal, courage and survival, one which features, as the title suggests, two old women.

Two Old Women by Velma Wallis is a quirky fable-like book I read about and was intrigued by, recommended by a fellow reader. It is an Alaskan legend of betrayal, courage and survival, one which features, as the title suggests, two old women. My Story by Jo Malone is one of the six memoirs I read in 2017 and the one that was the most intriguing and personal to me, not because I’m a fan of her perfumes, but because I too have a love of the aromas of plants, flowers, resins, herbs and like to create remedies from essential oils and mix them with other plant oils to use therapeutically.

My Story by Jo Malone is one of the six memoirs I read in 2017 and the one that was the most intriguing and personal to me, not because I’m a fan of her perfumes, but because I too have a love of the aromas of plants, flowers, resins, herbs and like to create remedies from essential oils and mix them with other plant oils to use therapeutically.

After her abrupt departure from Paris back to her father’s home in Montigny, to the village home where she grew up, I was curious to know what was to come of our troubled Claudine and her errant husband.

After her abrupt departure from Paris back to her father’s home in Montigny, to the village home where she grew up, I was curious to know what was to come of our troubled Claudine and her errant husband.

I loved Claudine at School for her exuberant overconfidence and love of nature, Claudine in Paris for her naivety and prudence, realising there was much about life she had still to learn and Claudine Married for the melancholy of marriage, of the realisation of her false ideals and indulgence of strong emotional impulses.

I loved Claudine at School for her exuberant overconfidence and love of nature, Claudine in Paris for her naivety and prudence, realising there was much about life she had still to learn and Claudine Married for the melancholy of marriage, of the realisation of her false ideals and indulgence of strong emotional impulses. The impulsive Claudine, thinking a marriage of her own making and choice (not one chosen by her father or suggested by a man who had feelings for her that weren’t reciprocated) embarks on her marital journey which begins with fifteen months of a vagabond life, travelling to the annual opera Festival de Bayreuth, in Germany, to Switzerland and the south of France.

The impulsive Claudine, thinking a marriage of her own making and choice (not one chosen by her father or suggested by a man who had feelings for her that weren’t reciprocated) embarks on her marital journey which begins with fifteen months of a vagabond life, travelling to the annual opera Festival de Bayreuth, in Germany, to Switzerland and the south of France. Their relationship plays itself out, up to the denouement, when Claudine seeking refuge decides to return to Montigny, to the safety of her childhood home, the woods, her animals whose loyalty she is assured of, and the affection of the maid Mélie and her humble, absent-minded father.

Their relationship plays itself out, up to the denouement, when Claudine seeking refuge decides to return to Montigny, to the safety of her childhood home, the woods, her animals whose loyalty she is assured of, and the affection of the maid Mélie and her humble, absent-minded father. If Claudine at School represents the unfettered, exuberant joys of teenage freedom, of the innocent and immature love between friends and the cruel indulgences of playful spite, Claudine in Paris is the slap in the face of regarding an approaching adult, urban world, one where the streets are inhabited by hidden dangers, the skies are more gloomy, people are not what they seem, even old friends from school become unrecognisable when the city and her frustrated inhabitants get their clutch onto the innocent.

If Claudine at School represents the unfettered, exuberant joys of teenage freedom, of the innocent and immature love between friends and the cruel indulgences of playful spite, Claudine in Paris is the slap in the face of regarding an approaching adult, urban world, one where the streets are inhabited by hidden dangers, the skies are more gloomy, people are not what they seem, even old friends from school become unrecognisable when the city and her frustrated inhabitants get their clutch onto the innocent.